Dal Review 93 121.Pdf (322.5Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yvette Nolan: Playwright in Context

University of Alberta Yvette Nolan: Playwright in Context bY Valerie Shantz A thesis submitted to the Facultv of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the recpirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Drama Edmonton, Alberta Spring, 1998 National tibrary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 335 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This thesis is concerned with providing a critical context for my work with Yvette Kolan, a Winnipeg based playwright. I chose to pursue this topic because as a drarnahirg and academic 1 have found few models on which to base our relationdup. My underlying assumptions were that in approachmg a dramatic text, a writer and her drarnaturg represent an ongoing histon of sirnilar relatiowhips. -

HIST 5222 Topics in Canadian Social History Fall 2014 Antimodernism, Modernism, and Postmodernism in Twentieth-Century Canadian Culture

HIST 5222 Topics in Canadian Social History Fall 2014 Antimodernism, Modernism, and Postmodernism in Twentieth-Century Canadian Culture This year’s version of HIST 5222 can be organized in two ways. There are currently 11 undergrads enrolled in HIST 4222; there is an additional undergrad who will be taking it as a GWST credit. Also, others have expressed interest in the course, but are “shopping around,” as Dalhousie undergrads do. HIST 4222 is scheduled for Mondays, 10:35-1:25. If the final numbers shrink, graduate students can join the undergraduate version without any quality- based questions arising. If, however, undergrad demands remains high, and depending on graduate interest, it may be more productive to have a second version of the class, with the graduate students & a few undergrads with similar research interests. In terms of the graduate workload, greater than that of the undergraduate version: 1. The case study essay is to be approximately 3000 words (10 pages, with footnotes) in length. 2. The research essay is to be approximately 6000 words (20 pages, with footnotes) in length. 3. Finally, each graduate student will be assigned two additional articles, agreed to by the student and instructor after consultation. Interested students are asked to email me, [email protected], between Friday, Sept 4th, and Sunday, Sept 6th, so that I can assess demand before Monday’s first meeting. Once we have decided on the final format of HIST 5222, I will draw up an official syllabus with proper meeting dates. HIST 4222/5222 Topics in Canadian Social History Fall 2014 Antimodernism, Modernism, and Postmodernism in Twentieth-Century Canadian Culture Todd McCallum [email protected] McCain 1162, 902 494 3643 What follows is the class schedule; the full syllabus, with accompanying material on university, faculty and departmental regulations, will be distributed in class. -

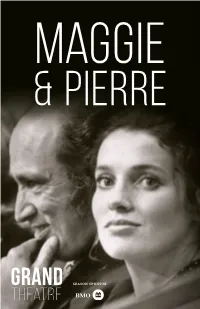

Maggie & Pierre

• VIDEO on-line cut took 20 hours. be done in TV, and what can be done by able at the end of the first year. • "People who don't know the show think The music came together smoothly. film personnel in TV." When he was in No TV sale has been made to the it's tied to current events and assume it's John Mills-Cockell, at the time doing a Hollywood in 1982, says Pickford, "Film United States or Europe, though a Bri no longer relevant today. I feel the show show at Toronto Free Theatre, wrote people were just starting to realize tish distributor, London Films, is hand can surface in five years and be able to the original score in two days. lilt was they'd better learn video ifthey wanted ling European sales and Butler travelled stand on its own." And please, says the like a Christmas gift," said Griffiths. Two to continue editing. In the late seven to MIP-TV in Cannes this spring to actress, don't call it satire. "I hate that Rolling Stones songs were used in the ties, video was considered a toy. Only _promote the show. Though he says it's word and its connotation that the play is show, "Paint It Black" and "Wild Hor recently has there been recognition "reasonably possible to get all its costs spiteful" Director Lavut agrees: the ses", but those aren't the Stones on the (from film people) of its real potential back in Canada," Butler is hopeful show, subtitled "A fantasy of love, poli soundtrack. -

WHEN YOU ADMIT YOU're a THIEF, THEN YOU CAN BE HONOURABLE" Native/ Non-Native Collaboration in " the Book of Jessica"

"WHEN YOU ADMIT YOU'RE A THIEF, THEN YOU CAN BE HONOURABLE" Native/ Non-Native Collaboration in " The Book of Jessica" Helen Hoy A SUBJECT MUCH BRUITED ABOUT JUST NOW in Canadian literary circles is the question of the appropriation of Native materials by non- Native authors.1 This raises by implication the epistemological and cultural violence which can be done (is necessarily done?) to Native texts by non-Native readings of them. Is teaching and criticism of these texts, by non-Natives, another form of cultural appropriation? In Canadian literature, The Book of Jessica, a collaborative effort by Métis writer Maria Campbell and Scottish-Canadian actress/playwright Linda Griffiths excavating the problematics of their earlier collaboration on a script of Campbell's life, provides detailed ground for an investigation of these issues. A vexed and troubling text — from the placement of Griffiths' name first in the attributing of authorship, to the devolvement of ultimate editorial responsibility eventually to her — The Book of Jessica, in all its ambiva- lence, can be read as modelling aspects of the white scholar/Native writer relation- ship. From its material conditions of production to the implications of Campbell's extra-textual decision to put her energies into Native politics rather than the book, the text both glosses and itself enacts postcolonial problems of gatekeeping, cultural impasse, and imbalances of power, while simultaneously insisting on the mutual imperative to communicate. My article will pair this concrete enactment of the politics of cross-cultural communication with current postcolonial/feminist theory on issues of appropriation and what Gayatri Spivak calls "the epistemic violence of imperialism." It will study how the theory illuminates the practice and how the practice illuminates the theory. -

Work from Linda Griffiths!!!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PLEASE ADD TO YOUR LISTINGS October 999,9, 2007 Nightwood Theatre presents the awardaward----winningwinning new work from Linda Griffiths!!! “[Linda] Griffiths is one of Canada's 'originals' known not only for the quality of her work, but for the sheer range of her career.” Macleans Magazine "Endlessly witty, vigorous, funny…brilliantly inventive…" Calgary Herald Age of Arousal By Linda Griffiths Directed by Maja Ardal Starring Clare Coulter , Sarah Dodd , Maggie Huculak , Ellen-Ray Hennessy , Gemma James-Smith and Dylan Smith Set and Costume Design by Julia Tribe , Lighting Design by Kimberly Purtell , Composition by E.C. Woodley November 17 to December 16, 2007 at Factory Theatre, Mainstage By the awardaward----winningwinning writer of Maggie and Pierre and Alien CCreaturesreatures TorTorToronto,Tor onto, ON… The setting is 1885: a time of great passion, great confusion. Mary Barfoot, an ex-militant suffragette, runs a school for secretaries with her beloved Rhoda. The school’s invasion by three spinster sisters and a charismatic cad named Everard, creates a catalyst for political, sexual and emotional explosion. Ideas and libidos clash for dominance, as each character confronts the meaning of revolutionary courage. Nightwood Theatre, in association with Factory Theatre, is proud to present the Toronto premiere of LindaLinda Griffith’s Age of Arousal . Genre-busting, rule-bending and ambitiously original, Age of Arousal is a lavish, sexy and powerful ensemble piece about the forbidden and gloriously liberated self. This truly wonderful story is wildly based on George Gissing’s 1893 novel “The Odd Women.” Griffiths describes what drew her to Gissing’s book, “I found a battered paperback in a secondhand bookstore and bought it for a dollar. -

Paul Thompson

PAUL THOMPSON Director, Writer, Teacher, Administrator, Maverick and Innovator Paul William Thompson is one of the most remarkable and accomplished voices in Canadian theatre. Born in Charlottetown, P.E.I. in 1940, he was raised in the farming community of Listowel, Ontario, where he worked on his uncle’s farm in the summers. As a young boy he was a voracious reader and a gifted athlete, particularly excelling in wrestling. He began his undergraduate career at the University of Western Ontario, where he obtained his Honours B.A. (English and French), and in 1963 won a scholarship to the prestigious Sorbonne University in Paris, where his academic and creative life was transformed forever. There he first discovered the work of Roger Planchon at the Théâtre National Populaire in Lyon. After completing his M.A. in French (specializing in Theatre) at the University of Toronto, he returned to France to work with Planchon as stagiaire de la mise en scène (apprentice director), 1965–67. Upon his return to Canada he began his apprenticeship with the legendary Jean Gascon at The Stratford Festival, where he worked as his assistant director until 1970. In 1970 Thompson was appointed Artistic Director of Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto, a ground-breaking theatre company born out of the cultural crucible that was Rochdale College, where he would help create some of the most influential theatrical events in Canadian history. During his 12-year artistic directorship he not only programmed and produced over 175 plays by authors ranging from Claude Jutra to Judith Thompson, but transformed the Canadian theatrical landscape forever with his own creations. -

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK ------X in Re : : Chapter 11 Case No

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ----------------------------------------------------------------x In re : : Chapter 11 Case No. MOTORS LIQUIDATION COMPANY, et al., : f/k/a General Motors Corp., et al. : 09-50026 (REG) : Debtors. : (Jointly Administered) ----------------------------------------------------------------x AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF NEW YORK ) ) ss: COUNTY OF SUFFOLK ) I, Barbara Kelley Keane, being duly sworn, depose and state: 1. I am an Assistant Director with The Garden City Group, Inc., the claims and noticing agent for the debtors and debtors-in-possession (the “Debtors”) in the above-captioned proceeding. Our business address is 105 Maxess Road, Melville, New York 11747. 2. On September 13, 2010, at the direction of Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP (“Weil”), counsel for the Debtors in the above-captioned case, I caused to be served by first class mail, postage prepaid, true and correct copies of the Notice of Hearing to Consider Approval of Debtors’ Proposed Disclosure Statement with Respect to Debtors’ Joint Chapter 11 Plan (“Notice of Disclosure Statement Hearing”), annexed hereto as Exhibit “A”, addressed to each of the individuals and entities in the service list attached hereto as Exhibit “B” (all parties listed in the Debtor’s Schedules of Assets and Liabilities, all parties who filed a Notice of Appearance, the master service list, and the creditor matrix not addressed in the following paragraphs). 3. Also on September 13, 2010, at the direction of Weil, I caused an appropriate number of true and correct copies of the Notice of Disclosure Statement Hearing to be served by hand delivery to Broadridge, Attn.: BSG Proxy Agent Services, JOB NOS. -

Alan Williams

22 Astwood Mews, London, SW7 4DE CDA +44 (0)20 7937 2749|[email protected] ALAN WILLIAMS AWARDS Nominated for Best Male Actor in a Leading Role [GENIE AWARDS, Canadian Academy of Cinematic Art, for “The Cockroach Who Ate Cincinnati”, 1997] Won Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role [Vancouver Association of Professional Theatres, for "Kemp" in "VIGIL", 1996] THEATRE FAITH, HOPE & CHARITY ‘Bernard’ Dir. Alexander Zeldin [National Theatre] THREE SISTERS ‘Ivan’ Dir Rebecca Frecknall [Almeida Theatre] GUNDOG ‘Mick’ Dir. Vicky Featherstone [Royal Court Theatre] MARY STUART ‘Talbot’ Dir. Robert Icke [Almeida Theatre] AS YOU LIKE IT ‘Corin’ Dir. Polly Findlay [National Theatre] HERE WE GO Dir. Dominic Cooke [National Theatre] LIGHT SHINING IN BUCKINGHAMSHIRE ‘Winstanley’ Dir. Lyndsay Turner [National Theatre] THE CRUCIBLE ‘Rev Parris’ Dir. James Brining [West Yorkshire Playhouse] THE RITUAL SLAUGHTER OF GORGE MASTROMAS ‘M’ Dir. Vicky Featherstone [Royal Court] THE PRESIDENT HAS COME TO SEE YOU ‘Dave’ Dir. Vicky Featherstone [Royal Court] TALK SHOW ‘Ron’ Dir. Caroline Steinbeis [Royal Court] MINT ‘Simon’ Dir. Caroline Steinbeis [Royal Court] KRAPP’S LAST TAPE ‘Krapp’ Dir. Jonathan Humphreys [Hull Truck] A THOUSAND STARS EXPLODE IN THE SKY ‘Jake Benton’ Dir. Sean Holmes [Lyric Hammersmith] EVERY GOOD BOY DESERVES FAVOUR ‘Colonel’ Dir. Tom Morris [National Theatre] WAR HORSE ‘Farmer Warren/Manfred’ Dirs. Marianne Elliott/Tom Morris [National Theatre & New London Theatre] THE BIRTHDAY PARTY ‘Petey’ Dir. David Farr [Lyric Hammersmith] A NUMBER ‘The Father’ Dir. Annabelle Comyn [Abbey Theatre] MEMORY Dir. Patrick Marber [Royal Court Theatre part of 50th anniversary celebrations] COMFORT ME WITH APPLES ‘Len’ Dir. Lucy Bailey [Hampstead Theatre] THE SCARLET LETTER ‘Brackett’ Dir. -

Maggie & Pierre House Program.Pdf

MAGGIE & PIERRE season sponsor Supporting the arts, locally. WELCOME At the height of Trudeaumania, while Pierre Minister. Immediately this play has become Elliot Trudeau was our Prime Minister, relevant and exciting all over again for Linda Griffiths brilliantly wrote a very top- new and delightful reasons. I love to think ical, focused play examining the extraordi- about Justin observing his parents’ colour- nary relationship of the Prime Minister and ful behaviour. There is little doubt that it his wife Margaret. informed him and helped shaped the man we know to be our Prime Minister. Griffiths then went on to star in the incredi- bly quirky love story, playing all three roles: We are thrilled to welcome timeshare Pro- reporter, Pierre, and Maggie. It toured all ductions, who created this version, which over Canada and remains one of the most premiered at the Thousand Islands Playhouse popular, important, and dazzling produc- in 2017. tions in Canadian theatre history. Welcome. I can’t imagine that Linda could have pre- dicted that the Trudeaus’ child, Justin, dennis garnhum Each year, through various donations would end up in Ottawa in the role of Prime artistic director and sponsorships, we are committed to helping our local communities. We would like to acknowledge the history of the traditional territory in which the Grand Theatre operates. We We’re proud to be the 2018/2019 season would also like to respect the longstanding relationships of the three local First Nations groups of this land and sponsor of the Grand Theatre. place in Southwestern Ontario. The three First Nations communities closest in proximity to the Grand are the Chippewa of the Thames First Nation (part of the Anishinaabe), the Oneida Nation of the Thames (part of the Haudenosaunee) and the Munsee-Delaware Nation (part of the Leni-Lunaape). -

Maggie & Pierre

• VIDEO on-line cut took 20 hours. be done in TV, and what can be done by able at the end of the first year. • "People who don't know the show think The music came together smoothly. film personnel in TV." When he was in No TV sale has been made to the it's tied to current events and assume it's John Mills-Cockell, at the time doing a Hollywood in 1982, says Pickford, "Film United States or Europe, though a Bri no longer relevant today. I feel the show show at Toronto Free Theatre, wrote people were just starting to realize tish distributor, London Films, is hand can surface in five years and be able to the original score in two days. lilt was they'd better learn video ifthey wanted ling European sales and Butler travelled stand on its own." And please, says the like a Christmas gift," said Griffiths. Two to continue editing. In the late seven to MIP-TV in Cannes this spring to actress, don't call it satire. "I hate that Rolling Stones songs were used in the ties, video was considered a toy. Only _promote the show. Though he says it's word and its connotation that the play is show, "Paint It Black" and "Wild Hor recently has there been recognition "reasonably possible to get all its costs spiteful" Director Lavut agrees: the ses", but those aren't the Stones on the (from film people) of its real potential back in Canada," Butler is hopeful show, subtitled "A fantasy of love, poli soundtrack. -

MAGGIE and PIERRE a FANTASY of LOVE, POLITICS and the MEDIA by Linda Griffiths with Paul Thompson

Press Information VIBRANT NEW WRITING | UNIQUE REDISCOVERIES Summer Season – May to August 2016 The European premiere MAGGIE AND PIERRE A FANTASY OF LOVE, POLITICS AND THE MEDIA by Linda Griffiths with Paul Thompson. Directed by Eduard Lewis. Produced by Kate Powell in association with Neil McPherson for the Finborough Theatre. Cast: Kelly Burke. “So now you have me, and the country, and everybody’s rooting for you, what are you going to do with the “all” that you’ve got?” In a new production commissioned by Finborough Theatre, the European premiere of Maggie and Pierre runs at the Finborough Theatre, playing Sunday and Monday evenings and Tuesday matinees from Sunday, 19 June 2016 (Press Night: Monday, 20 June 2016 at 7.30pm). In 2015, Justin Trudeau became Prime Minister of Canada in a landslide election victory. Maggie and Pierre is the story of his parents... It's the late 1960s. 19 year old Maggie Sinclair is a hippie free spirit, born out of love, socialism and a lot of dope. Pierre Trudeau is nearing 50, urbane, charismatic and soon-to-be elected as Prime Minister of Canada. Reason and passion soon collide as they meet, fall in love, marry, live together in the public spotlight, have three children, and break up in a very ugly and very public way. A Canadian classic, Maggie and Pierre is a tour de force one-woman play about the pressures of power and fame under the media spotlight. Maggie and Pierre quickly became a Canadian classic after its world premiere in 1980 at Toronto's Theatre Passe Muraille. -

25Th Street Theatre Collection

25TH STREET THEATRE COLLECTION A FINDING AID Prepared by Glen Makahonuk March 1988 25TH STREET THEATRE COLLECTION A FINDING AID Prepared by Glen Makahonuk March 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 1 - 8. Seasons pp. 7 - 36. paDer pp. 37 - 41. Finances pp. 42 - 44. IV. Board of Directors pp. 45 - 46. Resumes pp. 47 - 66. Agencies, Associations and Organizations pp. 67 - Material Pertaining to Other Theatres pp. 73 - 74 Introduction. 25th Street Theatre was founded in Saskatoon in 1972 by a number of residents who were concerned with' establishing a professional theatre with a ''prairie flavorw. In fact, the theatre's philosophy "is to produce new plays written by Canadians and to reflect the sensibilities of Canadians with special emphasis on the prairie region." The prairie theme has been dramatized by a number of shows including JAKOB KEPP, "the tragic story of a Saskatchewan farming family in the 1950sW, PRAIRIE PSALMS, a story about Saskatchewan's religious heritage, THE flUEEN'S COWBOY, which is based on a diary of William Parker, a North West Mounted Police Officer in the 1880s, and DONTCHA KNOW THE NORTH WIND AND YOU IN MY HAIR!, a Cree Indian love story. But the most important play to win national acclaim was PAPER WHEAT, the story of the farmers ' movement. 25th Street Theatre has produced more than 60 plays and sponsored or co-produced many others, including 21 contemporary Canadian hits. Many of these have been produced for staging by other professional theatres, or have been produced in other media i.e. radio, television, book, film and album.