[Name of Collection]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugh M. Gillis Papers

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Finding Aids 1995 Hugh M. Gillis papers Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids Part of the American Politics Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University, "Hugh M. Gillis papers" (1995). Finding Aids. 10. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids/10 This finding aid is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUGH M. GILLIS PAPERS FINDING AID OVERVIEW OF COLLECTION Title: Hugh M. Gillis papers Date: 1957-1995 Extent: 1 Box Creator: Gillis, Hugh M., 1918-2013 Language: English Repository: Zach S. Henderson Library Special Collections, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA. [email protected]. 912-478-7819. library.georgiasouthern.edu. Processing Note: Finding aid revised in 2020. INFORMATION FOR USE OF COLLECTION Conditions Governing Access: The collection is open for research use. Physical Access: Materials must be viewed in the Special Collections Reading Room under the supervision of Special Collections staff. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use: In order to protect the materials from inadvertent damage, all reproduction services are performed by the Special Collections staff. All requests for reproduction must be submitted using the Reproduction Request Form. Requests to publish from the collection must be submitted using the Publication Request Form. Special Collections does not claim to control the rights to all materials in its collection. -

The Southeastern Librarian

The Southeastern Librarian Volume 59 | Issue 2 Article 3 Summer 2011 State News Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seln Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation (2011) "State News," The Southeastern Librarian: Vol. 59 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seln/vol59/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Southeastern Librarian by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. http://selaonline.org/membership/mentorin g.htm to sign up as a mentor or mentee. The SELA Mentoring Program was developed to assist librarians, library paraprofessionals and library science students with their library careers. If you have any questions or are interested in becoming a mentor or mentee for the SELA Mentoring Program, please contact Hal Mendelsohn, [email protected], Chair of Ru Story-Huffman, Teacher of the Year the SELA Membership and Mentoring Award Winner Committee. STATE NEWS GEORGIA Georgia Southwestern State University The James Earl Carter Library on the campus of Georgia Southwestern State University has had eventful Fall and Spring Semesters. Ru Story-Huffman, the Library’s Reference Librarian and Dean Vera Weisskopf presents student Government Information Coordinator, Britton Weese the James Earl Carter received the Teacher of the Year Award at Library Award. Georgia Southwestern State University’s December 2010 graduation ceremony. The Library, in collaboration with GSW’s Gretchen Smith, the Library’s Collection Hurricane Otaku Club, presented Development Librarian, recently achieved “Transformers: The Movie” as part of the tenure status. -

World War II Teacher Notes

One Stop Shop For Educators 8H9 The student will describe the impact of World War II on Georgia’s development economically, socially, and politically. World war II had a major impact on the state of Georgia. While suffering though the Great Depression, many Georgians watched with interest or fear about the events that were taking place in Europe and Asia. Hitler’s Nazi Party had risen to power during the 1930s and sparked another world war with the 1939 attack on Poland. In the Pacific, Japan was focused on China, though Americans began to realize that they may set their sights on other islands in the Pacific, including American territories. Though America was technically neutral during the first years of the war, Roosevelt was “lending” military aid to Great Britain. America finally officially entered the war with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. As with World War I, once war was declared Georgians sprang into action. Many Georgians fought and died in the Army, Navy, and Marines. The military camps that were in the state became bases due to the large influx of military men and material. Georgia also became more industrialized as the Bell Aircraft company started building bombers and the navy ship yards in Brunswick and Savannah built “Liberty Ships” to aid in the war effort. Toward the end of the war, Georgia began to learn about the Holocaust and the horrific events that took place in Europe. Some of the survivors made their way to the United States, and to Georgia, to live and they told their stories. -

African American Heritage Trail

AFRICAN AMERICAN HERITAGE TRAIL Bartow County, Georgia Adairsville • Cassville • Cartersville • Euharlee Kingston • Lake Allatoona • Summer Hill INTRODUCTION African Americans have been part of American history for many centuries, with reports of free and enslaved Africans traveling to the Americas as early as the 1400s. It has been a fraught, tumultuous, and difficult history but one that also stands as testimony to the power of perseverance and the strength of the human spirit. What this brochure hopes to make clear, is that one cannot fully consider the Local African American history begins, as it does throughout the South, with history of Bartow County without understanding the history of its African slavery. Slavery was already present in Bartow County – originally Cass County American citizens. This history has been found embedded in the stories of – when it was chartered in 1832. Cotton and agriculture were the primary individuals who witnessed its unfolding. It has been found in the historical economic drivers but enslaved laborers were also used in the timber, mining, record, a trail of breadcrumbs left by those who bought land, built businesses, railroad, and iron industries. After emancipation, a strong African American and established themselves in spite of staggering odds. It has been found in the community emerged, which worked to support and empower its members even recollections of those who left Bartow County in search of a better life, and it has as they collectively faced the pressures of Jim Crow laws in the segregationist been found in struggles and achievements of those who stayed. This brochure South. Many of the families that established themselves in Bartow County is an effort to introduce what is known and share what has been discovered. -

Propst, Crecine Outline University System and Georgia Tech Priorities for the 1990 General Assembly Microelectronics Building De

n-Profit Organization .S. Postage AID Atlanta, Georgia Permit No. 1137 THE GEORGIA TECH WHISTLE VOLUME 16, NUMBER 3 - JANUARY 29, 1990 Propst, Crecine Outline University System And Georgia Tech Priorities For The 1990 General Assembly By Jackie Nemeth is in the business of furnishing both of these commodities. We are com- Chancellor of the University mitted to two overriding goals, giv- System of Georgia H. Dean Propst ing Georgia's young people a top and Georgia Thch President John P. flight technological education and Crecine addressed the University serving as an engine that drives System's and Georgia Thch's economic growth throughout the priorities for the 1990 General state." Assembly during a legislative brief- Propst said he was pleased with ing after the ribbon-cutting Gov. Joe Frank Harris' FY 91 ceremony for the Joseph Mayo Pet- recommendations for full funding of tit Building/Microelectronics the System's resident instruction Research Center on Jan. 17. formula; a 2.5 percent merit in- Georgia Thch Vice President for crease, in addition to the .5 percent External Affairs James Langley in- cost-of-living increase for Universi- troduced Propst and Crecine by ty System personnel; and a 35 per- Margaret Barrett saying "economic growth in this cent increase in employee health in- age demands a workplace that surance funding. He encouraged (L-R) Mrs. Marilyn Pettit Backlund, Mrs. Florence Pettit, Chris Backlund, Blake Backlund and President John P Crecine share a few words at the ribbon-cutting ceremony features skilled employees and cut- honoring Dr. Joseph Mayo Pettit, Georgia Tech's eighth president. -

Jimmy Carter

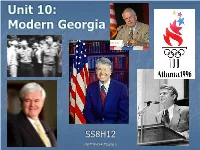

Unit 10: Modern Georgia SS8H12 Griffith-GA Studies Unit Focus The student will understand how various social, economic, and political changes have impacted life in Georgia since 1970. Students will discover ways that our economy is driven by production, distribution and consumption of goods and services. Students will evaluate the relevance and impact of the movement and migration of non-English speaking people into our state. They will also learn that as our society has become more complex, our governance has become more complex. Griffith-GA Studies THE BIG IDEA (Unit 10) SS8H12: The student will explain the importance of significant social, economic, and political developments in Georgia since 1970. Explain- to make understandable, to spell out; illustrate, interpret Griffith-GA Studies SS8H12a One Man, One Vote SS8H12a: Evaluate the consequences of the end of the county unit system and reapportionment. Evaluate: to make a judgment as to the worth or value of something; judge assess Griffith-GA Studies County Unit System SS8H12a Recall the county unit system… Established in 1917, the county unit system allotted votes in statewide elections by county classification but was disproportionate to actual population Gave political power to the rural counties and kept Democrats in power Unfair because… While rural counties made up 30% of the population or less, they had 59% of the voting power for statewide elected positions Griffith-GA Studies The County Unit System Why did GA Democrats care so much about keeping SS8H7a the County -

U.S. Senate Republican Leader Bob Dole Georgia State Convention Saturday, May 20, 1989 Atlanta, Georgia

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu U.S. SENATE REPUBLICAN LEADER BOB DOLE GEORGIA STATE CONVENTION SATURDAY, MAY 20, 1989 ATLANTA, GEORGIA Page 1 of 95 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas OSCAR, THANK YOUhttp://dolearchives.ku.edu VERY MUCH FOR THAT KIND INTRODUCTION. I ALSO WANT TO THANK YOU FOR ALL THE GOOD WORK YOU DID FOR ME AND ELIZABETH DURING THE PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN . WE'RE GRATEFUL. \ I I KNOW THESE ARE EXCITING TIMES FOR GEORGIA REPUBLICANS; AND I AM VERY PLEASED TO BE A PART OF IT HERE TODAY. YOU HAVE SOME IMPORTANT DECISIONS TO MAKE THIS WEEKEND, INCLUDING THE SELECTION OF A NEW STATE CHAIRMAN. -2- Page 2 of 95 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas SO LET ME TAKEhttp://dolearchives.ku.edu THIS OPPORTUNl1Y TO SALUTE THE WORK OF A GOOD MAN, YOUR SOON-TO-BE FORMER CHAIRMAN JOHN STUCKEY. UNDER -HIS LEADERSHIP, THE GEORGIA REPUBLICAN PAR1Y HAS MADE HISTORIC GAINS ACROSS-THE-BOARD. THANKS TO YOU,- JOHN,THE PAR1Y IS ON THE MOVE AND THE FUTURE LOOKS BRIGHT, INDEED. > -3- Page 3 of 95 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas GEORGIAhttp://dolearchives.ku.edu SUCCESS STORY NO DOUBT ABOUT IT, THE DAYS OF THE "SOLID SOUTH" ARE OVER FOR THE DEMOCRATS. IT'S "SOLID" ALL RIGHT -- FOR RONALD REAGAN AND GEORGE BUSH. WHAT WE HAVE TO DO NOW IS MAKE IT JUST AS "SOLID" FOR REPUBLICAN CANDIDATES AT EVERY LEVEL OF GOVERNMENT -- IN GEORGIA AND IN EVERY OTHER SOUTHERN STATE. -

Carter Center News Summer 1987 One Copenhill, Atlanta, Ga 50307

CARTER CENTER NEWS SUMMER 1987 ONE COPENHILL, ATLANTA, GA 50307 Carter Center Dedicated Celebrating the Carter Vision To Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, the dedication of The Carter Center represents an opportunity to keep alive issues of vital importance to America and the world. On October 1, 1986, they reaffirmed their commitment to education, health, the environment, human rights, and the peaceful resolution of conflict. On a sunny fall morning, the Atlanta skyline a backdrop to Presidential protocol and academic pomp and circumstance, President Carter and Mrs. Carter were joined by President Reagan and Mrs. Reagan, Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young, Governor Joe Frank Harris, Senator Sam Nunn, Senator (then U.S. Representative) Wyche Fowler, Emory University President James T. Laney, and a crowd of 5,000 for the purpose of dedicating the Carter Center. President Reagan embraced the Center on behalf of the American people. Lauding its founder, former President Carter, for his passion, intellect, and commitment, Reagan thanked him for his contributions to the nation. A series of four interconnected circular buildings adjoining two man-made lakes and a traditional Japanese garden, the Carter Center sits nestled into a hill overlooking downtown Atlanta. It embraces its 30-acre site "in a manner reminiscent of the low, earth-hugging architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright," said the Arizona Republic. "It bespeaks the 'understated elegance' that Carter sought." The buildings house the office of the former President, the Jimmy Carter Library and Museum, the Carter Center of Emory University, Global 2000, Inc., the Carter-Menil Human Rights Foundation, and the Task Force for Child Survival. -

CONSTITUTION of the STATE of GEORGIA

CONSTITUTION of the STATE of GEORGIA Revised January 2013 Designated as The Constitution of the State of Georgia Copies may be obtained from: Brian P. Kemp Georgia Secretary of State 214 State Capitol Atlanta, Georgia 30334 The Office of the Secretary of State The Constitution of the State of Georgia is the governing document of the state of Georgia. It outlines the three branches of government. The executive branch is headed by the Governor. The legislative branch is comprised of the bicameral General Assembly. The judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Court. Besides providing for the organization of these branches, the Constitution carefully outlines which powers each branch may exercise. The Constitution of the State of Georgia was ratified on November 2, 1982 by a vote of the people and became effective on July 1, 1983. It is one of the newest state constitutions in the United States of America and is the 10th Constitution of the State of Georgia, replacing the previous 1976 Constitution. I am pleased to provide the Constitution of the State of Georgia to you. The Constitution is a representation of our great state and its citizens. Please let me know if I can ever be of service to you. For any issues regarding voting, corporate registrations, securities or professional licensing, please do not hesitate to call the Office of the Secretary of State at 404-656-2881. Sincerely, Brian P. Kemp Georgia Secretary of State Designated as The Constitution of the State of Georgia CONSTITUTION OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLE I. -

Historical Highlights / Publications

UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF GEORGIA Brief History The beginnings of public higher education in the State can be traced to 1784 when the General Assembly set aside 40,000 acres of land for the endowment of "a college or seminary of learning." During the following year, a charter was granted for the establishment of Franklin College, now the University of Georgia. The state later provided appropriations for establishing the following branches: School of Technology in Atlanta, 1885 (now Georgia Tech); Georgia Normal and Industrial College for Girls, Milledgeville, 1889 (now Georgia College & State Univ.); Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youths, Savannah, 1890 (now Savannah State University); and the South Georgia Normal School, Valdosta, 1906 (now Valdosta State University). Later, the legislature established an agricultural and mechanical arts (A&M) school in each congressional district. In 1929, Governor L. G. Hardman established a committee charged with recommending reorganization of higher education. The most significant idea was the creation of a central governing board. On August 28, 1931, the Reorganization Act was signed which created the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia. The Act called for the governor to appoint eleven members, one from each congressional district, and one at large. In its January 1932 meeting, the Board adopted the following Statement of Plan: It is the conviction of the Board of Regents that the people of Georgia intended to ordain by the Act creating the Board that the twenty-six institutions comprising the University System should no longer function as separate, independent, and unrelated entities competing with each other for patronage and financial support. -

2013 Annual Report

are together we We open doors UGA and provide opportunities The University of Georgia 2012-13 Office of The President The University of Georgia The Administration Building Athens, Georgia 30602 Jere W. Morehead, President ([email protected]) Libby V. Morris, Interim Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost ([email protected]) Thomas S. Landrum, Vice President for Development and Alumni Relations ([email protected]) Thomas H. Jackson,Jr., Vice President for Public Affairs ([email protected]) Annual Report Donors to Letter from the 21st President 2 Letter from the 22nd President 5 Letter from the Outgoing Chair 6 Letter from the Incoming Chair 9 Introducing the University’s Strategic Plan for 2020 10 Teaching for a World-Class Learning Experience 13 Research for the 21st Century 18 Serving the Citizens 22 Financial Statements 26 contents Honor Roll of Donors 28 Administration 69 C2 President’s Report to Donors 1 It has been an honor and a privilege to serve as president of the University of Georgia these 16 years. Together, we have moved UGA into a place of prominence among America’s great public universities, all while focused on a mission of serving the people of Georgia through teaching, research and public service. What I value most from my time in this office are the relationships I have developed with the people who care deeply about this place. The chairs of the Foundation throughout my time here have been true servants of the university, focused on the mission and working to secure the financial resources to support it. The members of the senior administrative team have worked very hard to secure the future of Georgia’s flagship university. -

State Representatives from Bartow County Sponsor Wide Slate of Bills

THURSDAY January 23, 2020 BARTOW COUNTY’S ONLY DAILY NEWSPAPER 75 cents Etowah Indian Mounds to offer free admission on Super Museum Sunday BY MARIE NESMITH [email protected] In honor of Super Museum Sunday, Etowah Indian Mounds will waive admission fees Feb. 9. “Super Museum Sunday started off with museums and historic homes along the Georgia coast, years ago, as a way of offering winter vacationers something to do in the off months, for free, in the hopes that it would spur retail sales,” said Keith Bailey, curator for the Etowah Indian Mounds State Historic Site. “In 2017, Etowah Mounds and other his- toric sites, throughout the state, joined in as participants, to make it a statewide event, giving people something to do in the cold of winter, when people often feel it is too cold to do things outside.” Open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Feb. 9, Etowah Indian Mounds will offer special programming, such as compact guided tours at 10 a.m., 11 a.m., 12:30 p.m. and 3:30 p.m. During the educational walk, visitors will learn more about the 54-acre site, where several thousand American Indians lived from A.D. 1000 to A.D. 1550. Regarded as the most intact Mississippian Culture site in the Southeast, Etowah Indian Mounds at 813 Indian Mounds Road in Cartersville safeguards six earthen mounds, a village area, a plaza, bor- row pits and a defensive ditch. “Archaeologist and author Adam King will be here at 2 JAMES SWIFT/THE DAILY TRIBUNE NEWS p.m.