Nothing Shall Hurt You and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture' Exhibition Catalog Anne M Giangiulio, University of Texas at El Paso

University of Texas at El Paso From the SelectedWorks of Anne M. Giangiulio 2006 'Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture' Exhibition Catalog Anne M Giangiulio, University of Texas at El Paso Available at: https://works.bepress.com/anne_giangiulio/32/ Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture Organized by the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso This publication accompanies the exhibition Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture which was organized by the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso and co-curated by Kate Bonansinga and Vincent Burke. Published by The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX 79968 www.utep.edu/arts Copyright 2006 by the authors, the artists and the University of Texas at El Paso. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the University of Texas at El Paso. Exhibition Itinerary Portland Art Center Portland, OR March 2-April 22, 2006 Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX June 29-September 23, 2006 San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts San Angelo, TX April 20-June 24, 2007 Landmark Arts Texas Tech University Lubbock, TX July 6-August 17, 2007 Southwest School of Art and Craft San Antonio, TX September 6-November 7, 2007 The exhibition and its associated programming in El Paso have been generously supported in part by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Texas Commission on the Arts. -

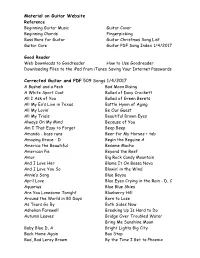

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

In Memoriam Frederick Dougla

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection CANNOT BE PHOTOCOPIED * Not For Circulation Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection / III llllllllllll 3 9077 03100227 5 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection jFrebericfc Bouglass t Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection fry ^tty <y /z^ {.CJ24. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Hn flDemoriam Frederick Douglass ;?v r (f) ^m^JjZ^u To live that freedom, truth and life Might never know eclipse To die, with woman's work and words Aglow upon his lips, To face the foes of human kind Through years of wounds and scars, It is enough ; lead on to find Thy place amid the stars." Mary Lowe Dickinson. PHILADELPHIA: JOHN C YORSTON & CO., Publishers J897 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Copyright. 1897 & CO. JOHN C. YORSTON Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection 73 7^ In WLzmtxtrnm 3fr*r**i]Ch anglais; "I have seen dark hours in my life, and I have seen the darkness gradually disappearing, and the light gradually increasing. One by one, I have seen obstacles removed, errors corrected, prejudices softened, proscriptions relinquished, and my people advancing in all the elements I that make up the sum of general welfare. remember that God reigns in eternity, and that, whatever delays, dis appointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty and humanity will prevail." Extract from address of Mr. -

Super Saturday, Wonderful Weekend Draw Blow For

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2011 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here SUPER SATURDAY, WONDERFUL WEEKEND DRAW BLOW FOR ARC FAVORITES By any measure, it is a Super Saturday today, as no Ante-post favorites So You Think (NZ) (High fewer than 13 graded events, each with varying Chaparral {Ire}) and Sarafina (Fr) (Refuse To Bend {Ire}) degrees of impact on Breeders= Cup weekend Nov. 4 will be forced to overcome wide post positions in and 5, will be contested from >sea to shining sea.= The tomorrow=s G1 Qatar Prix de l=Arc de Triomphe at races have attracted 3 reigning Longchamp. Only Dalakhani (Ire) and Sakhee have Eclipse Award winners, a managed to win from double-figure stalls since 1993, quartet of others who were and both Sarafina (13) and So You Think (14) face an among finalists for instant disadvantage as they bid to crown successful championship honors and a campaigns. So You Think, who will be partnered once Classic-winning 3-year-old of again by Seamus Heffernan after the pair were this season. For good measure, successful in the July 2 G1 Eclipse S. at Sandown and two-time Eclipse Award winner G1 Irish Champion S. at Leopardstown Sept. 3, was and 2010 Horse of the Year not the only Ballydoyle raider to fare badly with the finalist Goldikova (Ire) (Anabaa) draw, as stable companion Treasure Beach (GB) (Galileo will prep for a fourth {Ire}) will exit from the 12 hole under Colm consecutive victory in the GI O=Donoghue. Arc Preview cont. p4 Stay Thirsty Horsephotos Breeders= Cup Mile when she goes postward in the G1 Prix de la Foret on the Arc undercard. -

Mythology Teachers' Guide

Teachers’ Guide Mythology: The Gods, Heroes, and Monsters of Ancient Greece by Lady Hestia Evans • edited by Dugald A. Steer • illustrated by Nick Harris, Nicki Palin, and David Wyatt • decorative friezes by Helen Ward Age 8 and up • Grade 3 and up ISBN: 978-0-7636-3403-2 $19.99 ($25.00 CAN) ABOUT THE BOOK Mythology purports to be an early nineteenth-century primer on Greek myths written by Lady Hestia Evans. This particular edition is inscribed to Lady Hestia’s friend John Oro, who was embarking on a tour of the sites of ancient Greece. Along his journey, Oro has added his own notes, comments, and drawings in the margins — including mention of his growing obsession with the story of King Midas and a visit to Olympus to make a daring request of Zeus himself. This guide to Mythology is designed to support a creative curriculum and provide opportunities to make links across subjects. The suggested activities help students make connections with and build on their existing knowledge, which may draw from film, computer games, and other popular media as well as books and more traditional sources. We hope that the menu of possibilities presented here will serve as a creative springboard and inspiration for you in your classroom. For your ease of use, the guide is structured to follow the book in a chapter-by-chapter order. However, many of the activities allow teachers to draw on material from several chapters. For instance, the storytelling performance activity outlined in the section “An Introduction to Mythology” could also be used with stories from other chapters. -

Cutthroat 26 Copy FINAL AUG

1 EDITOR IN CHIEF: PAMELA USCHUK FICTION EDITOR: WILLIAM LUVAAS ASSISTANT FICTION EDITOR: JULIE JACOBSON GUEST POETRY EDITOR: LESLIE CONTRERAS SCHWARTZ POETRY EDITOR: HOWIE FAERSTEIN POETRY EDITOR: TERI HAIRSTON POETRY EDITOR: MARK LEE POETRY EDITOR: WILIAM PITT ROOT MANAGING EDITOR: ANDREW ALLPORT DESIGN EDITOR: ALEXANDRA COGSWELL CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Sandra Alcosser, Charles Baxter, Frank Bergon, Janet Burroway, Robert Olen Butler, Ram Devineni, Joy Harjo, Richard Jackson, Marilyn Kallet, Zelda Lockhart, Demetria Martinez, John McNally, Dennis Sampson, Rebecca Seiferle, Luis Alberto Urrea, Lyrae van Clief, and Patricia Jabbeh Wesley. Jane Mead, Rick DeMarinis, Penelope Niven, and Red Bird, in memorium. Send submissions, subscription payments and inquiries to CUTTHROAT, A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS, 5401 N Cresta Loma Drive, Tucson, AZ 85704. ph: 970-903-7914 email: [email protected] Make checks payable to Cutthroat, A Journal of the Arts Subscriptions are $25 per two issues or $15 for a single issue. We are self-funded so all Donations gratefully accepted. Copyright@2021 CUTTHROAT, A Journal Of The Arts 2 CUTTHROAT THANKS WEBSITE DESIGN: LAURA PRENDERGAST PAMELA USCHUK COVER LAYOUT: PAMELA USCHUK MAGAZINE LAYOUT: PAMELA USCHUK LOGO DESIGN: LYNN MCFADDEN WATT FRONT COVER ART: ALBERT KOGEL “PESCADOS,” acrylic on canvas INSIDE ART: JACQUELINE JOHNSON, quilts JERRY GATES, oil pastels on paper RON FUNDINGSLAND, prints on paper AND THANK YOU TO: Andrew Allport, Howie Faerstein, CM Fhurman, Teri Hairston, Richard Jackson, Julie Jacobson, Marilyn Kallet, Tim Rien, William Pitt Root, Pamela Uschuk and Patricia Jabbeh Wesley, for serving as readers for our literary contests. To our final contest judges: Kimberly Blaeser, Poetry; Amina Gautier, Short Story; Fenton Johnson, Nonfiction. -

June 2020 #211

Click here to kill the Virus...the Italian way INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Table of Contents 1 Notams 2 Admin Reports 3-4-5 Covid19 Experience Flying the Line with Covid19 Paul Soderlind Scholarship Winners North Country Don King Atkins Stratocruiser Contributing Stories from the Members Bits and Pieces-June Gars’ Stories From here on out the If you use and depend on the most critical thing is NOT to RNPA Directory FLY THE AIRPLANE. you must keep your mailing address(es) up to date . The ONLY Instead, you MUST place that can be done is to send KEEP YOUR EMAIL UPTO DATE. it to: The only way we will have to The Keeper Of The Data Base: communicate directly with you Howie Leland as a group is through emails. Change yours here ONLY: [email protected] (239) 839-6198 Howie Leland 14541 Eagle Ridge Drive, [email protected] Ft. Myers, FL 33912 "Heard about the RNPA FORUM?" President Reports Gary Pisel HAPPY LOCKDOWN GREETINGS TO ALL MEMBERS Well the past few weeks and months have been a rude awakening for our past lifestyles. Vacations and cruises cancelled, all the major league sports cancelled, the airline industry reduced to the bare minimum. Luckily, I have not heard of many pilots or flight attendants contracting COVID19. Hopefully as we start to reopen the USA things will bounce back. The airlines at present are running at full capacity but with several restrictions. Now is the time to plan ahead. We have a RNPA cruise on Norwegian Cruise Lines next April. Things will be back to the new normal. -

Shotgun Wedding by Tiffany Zehnal

Shotgun Wedding by Tiffany Zehnal Writer's First Draft May 22, 2006 FADE IN: EXT. A SMALL TEXAS TOWN - EARLY MORNING The kind of town where people get by and then die. The morning sun has no choice but to come up over the horizon. A SQUIRREL... scurries across a telephone line... down a pole... over a "DON'T MESS WITH TEXASS" sticker... into an apartment complex parking lot... EXT. SHERWOOD FOREST APARTMENT COMPLEX ...and under a BLACK EXTENDED CAB PICK-UP TRUCK that faces out of its parking spot. It's filthy. As evident by the dirt graffiti: "F'ing Wash Me!" The driver's side mirror hangs by a metal thread. On the windshield, ONE DEAD GOLDFISH, eyes wide open... ...and in the back window, an EMPTY GUN RACK. INT. BATHROOM A box of AMMUNITION. A pair of female hands with a perfect FRENCH MANICURE loads bullets into a SHOTGUN. One by one. The only jewelry, a THIN, SILVER BAND on the middle finger of her left hand. INT. BEDROOM A clock radio -- the numbers flip from 5:59 to 6:00. COUNTRY MUSIC fills the room as a hand reaches over and HITS the snooze button. A millisecond of silence. An OFF-SCREEN SHOTGUN IS COCKED. The mound in the middle of the bed lifts his eye mask. This is WYATT, 34, handsome in a ruggedly casual never-washes-his- jeans way. He has a SMALL MOLE on his neck which, if you squint, looks like Texas. Wyatt’s all about maintaining the status quo. If he used words like status quo. -

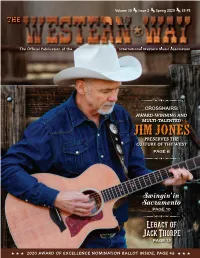

Spring 2020 $5.95 THE

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2020 $5.95 THE The Offi cial Publication of the International Western Music Association CROSSHAIRS: AWARD-WINNING AND MULTI-TALENTED JIM JONES PRESERVES THE CULTURE OF THE WEST PAGE 6 Swingin’ in Sacramento PAGE 10 Legacy of Jack Thorpe PAGE 12 ★ ★ ★ 2020 AWARD OF EXCELLENCE NOMINATION BALLOT INSIDE, PAGE 46 ★ ★ ★ __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 1 3/18/20 7:32 PM __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 2 3/18/20 7:32 PM 2019 Instrumentalist of the Year Thank you IWMA for your love & support of my music! HaileySandoz.com 2020 WESTERN WRITERS OF AMERICA CONVENTION June 17-20, 2020 Rushmore Plaza Holiday Inn Rapid City, SD Tour to Spearfish and Deadwood PROGRAMMING ON LAKOTA CULTURE FEATURED SPEAKER Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve SESSIONS ON: Marketing, Editors and Agents, Fiction, Nonfiction, Old West Legends, Woman Suffrage and more. Visit www.westernwriters.org or contact wwa.moulton@gmail. for more info __WW Spring 2020_Interior.indd 1 3/18/20 7:26 PM FOUNDER Bill Wiley From The President... OFFICERS Robert Lorbeer, President Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert’s Marvin O’Dell, V.P. Belinda Gail, Secretary Diana Raven, Treasurer Ramblings EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Marsha Short IWMA Board of Directors, herein after BOD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS meets several times each year; our Bylaws specify Richard Dollarhide that the BOD has to meet face to face for not less Juni Fisher Belinda Gail than 3 meetings each year. Jerry Hall The first meeting is usually in the late January/ Robert Lorbeer early February time frame, and this year we met Marvin O’Dell Robert Lorbeer Theresa O’Dell on February 4 and 5 in Sierra Vista, AZ. -

Guitar Magazine Master Spreadsheet

Master 10 Years Through the Iris G1 09/06 10 years Wasteland GW 4/06 311 Love Song GW 7/04 AC/DC Back in Black + lesson GW 12/05 AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap G1 1/04 AC/DC For Those About to Rock GW 5/07 AC/DC Girls Got Rhythm G1 3/07 AC/DC Have a Drink On Me GW 12/05 ac/dc hell's bells G1 9/2004 AC/DC hell's Bells G 3/91 AC/DC Hells Bells GW 1/09 AC/DC Let There Be Rock GW 11/06 AC/DC money talks GW 5/91 ac/DC shoot to thrill GW 4/10 AC/DC T.N.T GW 12/07 AC/DC Thunderstruck 1/91 GS AC/DC Thunderstruck GW 7/09 AC/DC Who Made Who GW 1/09 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie G1 10/06 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long GW 9/07 Accept Balls to the Wall GW 11/07 Aerosmith Back in the Saddle GW 12/98 Aerosmith Dream On GW 3/92 Aerosmith Dream On G1 1/07 Aerosmith Love in an Elevator G 2/91 Aerosmith Train Kept a Rollin’ GW 11/08 AFI Miss Murder GW 9/06 AFI Silver and Cold GW 6/04 Al DiMeola Egyptian Danza G 6/96 Alice Cooper No More Mr. Nice Guy G 9/96 Alice Cooper School's Out G 2/90 alice cooper school’s out for summer GW hol 08 alice in chains Dam That River GW 11/06 Alice in Chains dam that river G1 4/03 Alice In Chains Man in the Box GW 12/09 alice in chains them bones GW 10/04 All That Remains Two Weeks GW 1/09 All-American Rejects Dirty Little Secret GW 6/06 Allman Bros Midnight Rider GW 12/06 Allman Bros Statesboro Blues GW 6/04 Allman Bros Trouble no More (live) GW 4/07 Allman Bros.