Zhao Ziyang's Vision of Chinese Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Powerful patriots : nationalism, diplomacy, and the strategic logic of anti-foreign protest Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9z19141j Author Weiss, Jessica Chen Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Powerful Patriots: Nationalism, Diplomacy, and the Strategic Logic of Anti-Foreign Protest A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Jessica Chen Weiss Committee in charge: Professor David Lake, Co-Chair Professor Susan Shirk, Co-Chair Professor Lawrence Broz Professor Richard Madsen Professor Branislav Slantchev 2008 Copyright Jessica Chen Weiss, 2008 All rights reserved. Signature Page The Dissertation of Jessica Chen Weiss is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii Dedication To my parents iv Epigraph In regard to China-Japan relations, reactions among youths, especially students, are strong. If difficult problems were to appear still further, it will become impossible to explain them to the people. It will become impossible to control them. I want you to understand this position which we are in. Deng Xiaoping, speaking at a meeting with high-level Japanese officials, including Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Finance, Agriculture, and Forestry, June 28, 19871 During times of crisis, Arab governments demonstrated their own conception of public opinion as a street that needed to be contained. Some even complained about the absence of demonstrators at times when they hoped to persuade the United States to ease its demands for public endorsements of its policies. -

In Less Than a Decade, DUFF Mckagan Shot

36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 2:10 PM Page 36 36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 2:14 PM Page 37 Bulletproof In less than a decade, DUFF McKAGAN shot from strung-out GUNS N’ ROSES megastar to sober bass-groovin’ dude for VELVET REVOLVER. Bass Guitar’s E.E. Bradman gets the rock-solid bass man in his sight. BG 37 36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 4:25 PM Page 38 36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 5:22 PM Page 39 “Every good rock band has to . You need that something that moves people.” uff McKagan knows covers-only Spaghetti Incident and the so-so Live Era didn’t measure up to the band’s HAIR FORCE ONE: about missed opportuni- Duff, with Rose and Slash, debut, and by 1992 Izzy and Adler had been in his GN’R daze ties. He was, after all, the replaced by Gilby Clarke and Matt Sorum. In founding bassist of the 1993, McKagan released his first solo album, legendary Guns N’ Roses, Believe in Me. Guns eventually crumbled, leaving an uncompleted (and still unreleased) whose rock-star excesses, album, tentatively titled Chinese Democracy, volatile live shows and incendiary in the balance. albums made them the biggest band in McKagan’s second effort, Beautiful D Disease, was lost to record company politics, the world before they spluttered to a but he stayed busy producing Betty Blow- messy close a decade later. But McKa- torch, playing several instruments with gan—who after a drug-and-alcohol- Screaming Trees vocalist Mark Lanegan, and related pancreas explosion 10 years ago handling guitar and bass duties for Iggy Pop, was told by doctors that his next drink Ten Minute Warning, Loaded, the Neurotic Outsiders (with John Taylor of Duran Duran would kill him—also knows a thing or and Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols) and the two about second chances. -

Chen Xitong Report on Putting Down Anti

Recent Publications The June Turbulence in Beijing How Chinese View the Riot in Beijing Fourth Plenary Session of the CPC Central Committee Report on Down Anti-Government Riot Retrospective After the Storm VOA Disgraces Itself Report on Checking the Turmoil and Quelling the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion June 30, 1989 Chen Xitong, State Councillor and Mayor of Beijing New Star Publishers Beijing 1989 Report on Checking the Turmoil and Quelling the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion From June 29 to July 7 the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress - the standing organization of the highest organ of state power in the People's Republic of China - held the eighth meeting of the Seventh National People's Congress in Beijing. One of the topics for discussing at the meeting was a report on checking the turmoil and quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion in Beijirig. The report by state councillor and mayor of Beijing Chen Xitong explained in detail the process by which a small group of people made use of the student unrest in Beijing and turned it into a counter-revolutionary rebellion by mid-June. It gave a detailed account of the nature of the riot, its severe conse- quence and the efforts made by troops enforcing _martial law, with the help of Beijing residents to quell the riot. The report exposed the behind-the-scene activities of people who stub- bornly persisted in opposing the Chinese Communist Party and socialism as well as the small handful of organizers and schemers of the riot; their collaboration with antagonistic forces at home and abroad; and the atrocities committed by former criminals in beating, looting, burning and First Edition 1989 killing in the riot. -

Resource List

Resource List rative activities relating to June 4th. The Nomination of the Tiananmen Mothers for Web site contains information about ongo- the Nobel Peace Prize 2004 The 1989 ing and upcoming campaigns and rallies in http://209.120.234.77/64/press/ .2, Democracy Movement Hong Kong and overseas. It also provides TiananmenMothersPackage_2004_Final.pdf NO links to many other relevant Web sites. English COMPILED BY STACY MOSHER This packet of materials was prepared by Independent Federation of Chinese Stu- the Independent Federation of Chinese Stu- dents and Scholars dents and Scholars to support their nomi- WEB SITES: www.ifcss.net nation of the Tiananmen Mothers for the FORUM Chinese and English 2004 Nobel Peace Prize. 64 Memo The IFCSS was founded in Chicago in Princeton Professor Perry Link’s letter of http://www.64memo.org/index.asp August 1989 by more than 1,000 Chinese nomination can be read in Chinese at: RIGHTS Chinese student representatives from more than http://www.dajiyuan.com/gb/4/4/2/n499 Operated by Tiananmen veteran Feng 200 U.S. universities, and remains the 469.htm CHINA Congde and sponsored by HRIC, this Web most influential overseas Chinese student The text was transcribed from Link’s site provides an archive of documents, arti- group. Although less active in recent years, broadcast of the letter on Radio Free Asia. 79 cles and images relating to June 4th. IFCSS is organizing the collection of arti- cles, documents and photos relating to its Tiananmen Square, 1989: The Declassi- Boxun.com Tiananmen Feature upcoming 15th anniversary. fied History http://www.boxun.com/my-cgi/post/ http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/N TURES display_all.cgi?cat=64 June 4th Essays SAEBB16/ FEA Chinese http://www.dajiyuan.com/gb/nf2976.htm English Boxun’s special section of photos, articles Chinese An archive of official documents of the U.S. -

Continuing Crackdown in Inner Mongolia

CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) CONTINUING CRACKDOWN IN INNER MONGOLIA Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ Los Angeles $$$ London Copyright 8 March 1992 by Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-059-6 Human Rights Watch/Asia (formerly Asia Watch) Human Rights Watch/Asia was established in 1985 to monitor and promote the observance of internationally recognized human rights in Asia. Sidney Jones is the executive director; Mike Jendrzejczyk is the Washington director; Robin Munro is the Hong Kong director; Therese Caouette, Patricia Gossman and Jeannine Guthrie are research associates; Cathy Yai-Wen Lee and Grace Oboma-Layat are associates; Mickey Spiegel is a research consultant. Jack Greenberg is the chair of the advisory committee and Orville Schell is vice chair. HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Helsinki division. Today, it includes five divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, as well as the signatories of the Helsinki accords. -

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership

Elite Politics and the Fourth Generation of Chinese Leadership ZHENG YONGNIAN & LYE LIANG FOOK* The personnel reshuffle at the 16th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party is widely regarded as the first smooth and peaceful transition of power in the Party’s history. Some China observers have even argued that China’s political succession has been institutionalized. While this paper recognizes that the Congress may provide the most obvious manifestation of the institutionalization of political succession, this does not necessarily mean that the informal nature of politics is no longer important. Instead, the paper contends that Chinese political succession continues to be dictated by the rule of man although institutionalization may have conditioned such a process. Jiang Zemin has succeeded in securing a legacy for himself with his “Three Represents” theory and in putting his own men in key positions of the Party and government. All these present challenges to Hu Jintao, Jiang’s successor. Although not new to politics, Hu would have to tread cautiously if he is to succeed in consolidating power. INTRODUCTION Although the 16th Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Congress ended almost a year ago, the outcomes and implications of the Congress continue to grip the attention of China watchers, including government leaders and officials, academics and businessmen. One of the most significant outcomes of the Congress, convened in Beijing from November 8-14, 2002, was that it marked the first ever smooth and peaceful transition of power since the Party was formed more than 80 years ago.1 Neither Mao Zedong nor Deng Xiaoping, despite their impeccable revolutionary credentials, successfully transferred power to their chosen successors. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Testimony of Zhou Fengsuo, President Humanitarian China and Student Leader of the 1989 Tiananmen Square Demonstrations

Testimony of Zhou Fengsuo, President Humanitarian China and student leader of the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations Congressman McGovern, Senator Rubio, Members of Congress, thank you for inviting me to speak in this special moment on the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen Massacre. As a participant of the 1989 Democracy Movement and a survivor of the Massacre started in the evening of June 3rd, it is both my honor and duty to speak, for these who sacrificed their lives for the freedom and democracy of China, for the movement that ignited the hope of change that was so close, and for the last 30 years of indefatigable fight for truth and justice. I was a physics student at Tsinghua University in 1989. The previous summer of 1988, I organized the first and only free election of the student union of my department. I was amazed and encouraged by the enthusiasm of the students to participate in the process of self-governing. There was a palpable sense for change in the college campuses. When Hu Yaobang died on April 15, 1989. His death triggered immediately widespread protests in top universities of Beijing, because he was removed from the position of the General Secretary of CCP in 1987 for his sympathy towards the protesting students and for being too open minded. The next day I went to Tiananmen Square to offer a flower wreath with my roommates of Tsinghua University. To my pleasant surprise, my words on the wreath was published the next day by a national official newspaper. We were the first group to go to Tiananmen Square to mourn Hu Yaobang. -

Guns N' Roses

Guns N’ Roses ‘Live And Let Die’ Guns N’ Roses SONG TITLE: LIVE AND LET DIE ALBUM: USE YOUR ILLUSION I RELEASED: 1991 LABEL: GEFFEN GENRE: HARD ROCK PERSONNEL: W. AXL ROSE (VOX) SLASH (GTR) IZZY STRADLIN (GTR) DUFF MCKAGAN (BASS) MATT SORUM (DRUMS) DIZZY REED (KEYS) UK CHART PEAK: N/A US CHART PEAK: 33 BACKGROUND INFO seven years before Axl Rose decided to fire all the members who remained in the mid 1990s. Sorum McCartney and James Bond get the Guns N’ Roses remained faithful to guitarist Slash and played in the treatment. This popular cover was released in 1991 latter’s Velvet Revolver band. Prior to that, Sorum at a time when G N’ R was probably the most famous was a regular guest drummer for The Cult and played band on the planet. This is naturally a heavier version drums for a very young Tori Amos on her first tour. than the 1972 original but they still captured a lot of More recently Sorum has contributed to a Buddy Rich the song’s underlying humour and playfulness. The tribute album which showcased his technical abilities song features a mix of regular and half-time grooves in jazz drumming. along with a reggae-inspired middle section requiring the drummer to be alert and keep it tight. The player featured here is Matt Sorum. RECOMMENDED LISTENING The G N’ R legacy is based on six studio albums THE BIGGER PICTURE of which the most important by far is their debut, Appetite for Destruction (1987). This record single Matt Sorum’s big rock sound in Guns N’ Roses handedly propelled the band to superstardom and tends to obscure other aspects of his playing. -

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

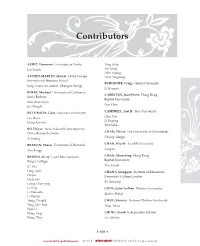

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

China's 17Th Communist Party Congress, 2007: Leadership And

Order Code RS22767 December 5, 2007 China’s 17th Communist Party Congress, 2007: Leadership and Policy Implications Kerry Dumbaugh Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 17th Congress, held from October 15 - 21, 2007, demonstrated the Party’s efforts to try to adapt and redefine itself in the face of emerging economic and social challenges while still trying to maintain its authoritarian one-Party rule. The Congress validated and re-emphasized the priority on continued economic development; expanded that concept to include more balanced and sustainable development; announced that the Party would seek to broaden political participation by expanding intra-Party democracy; and selected two potential rival candidates, Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang, with differing philosophies (rather than one designated successor-in- waiting) as possibilities to succeed to the top Party position in five years. More will be known about the Party’s future prospects and the relative influence of its two potential successors once the National People’s Congress meets in early 2008 to select key government ministers. This report will not be updated. Periodically (approximately every five years) the Chinese Communist Party holds a Congress, attended by some 2,000 senior Party members, to authorize important policy and leadership decisions within the Party for the coming five years. In addition to authorizing substantive policies, the Party at its Congress selects a new Central Committee, comprised of the most important figures in the Party, government, and military.1 The Central Committee in turn technically selects a new Politburo and a new Politburo Standing Committee, comprised of China’s most powerful and important leaders. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ………………………………………………………………………………………………………