Annual Report 2017-18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OUTCOME BUDGET DOON UNIVERSITY Dehradun

OUTCOME BUDGET 2012-13 DOON UNIVERSITY Dehradun Mothrowala Road, Kedarpur P.O. Ajabpur Dehradun-248001 Uttarakhand Doon University, Outcome Budget, 2012-13 Page 1 Doon University, Dehradun Outcome Budget 2012-13 1. About The University Doon University draws its profile from the vision of the State to transform the higher education of the region by creating centres of excellence. The Government of Uttarakhand approved the establishment of a University in 2005 vide Uttararanchal Adhiniyam Sankhya 18 of 2005 that would become a centre of higher learning in contemporary disciplines. The main campus of the University is located in an area of 22.26 hectares at Kedarpur, Dehradun. A second campus is proposed to be established on 40.47 hectares of land at Sahaspur. Doon University is a residential University. Students are expected to stay in the Hostel in the Campus as they will be required to participate in group discussions and attend tutorials after the regular classes are over which will help the student to clarify any doubts in the courses and improve their interpersonal and communication skills. The University is supported and funded by the State Government for its financial requirements under the recurring and non-recurring expenditures. The University has now obtained 12(B) Status under the UGC Act of 1956 and has now become eligible to obtain Development Assistance from University Grants Commission. Vision, Mission and Character of the University Vision of the University In accordance with the provision in Section 5(1) of the Act No 18 of 2005, Doon University shall become a Centre of Excellence in the chosen areas of studies, and shall carry out research for the advancement and dissemination of knowledge. -

Making Way: Securing the Chilla-Motichur Corridor to Protect

OCCASIONAL REPORT NO. 10 MAKING WAY Till recent past the elephant population of Chilla on the east bank of the Ganga and Motichur, on the west, was one with regular movement between these two forest ranges of Rajaji National Park. Securing the Chilla-Motichur Corridor This movement, at one point, came to a virual halt because of to protect elephants of Rajaji National Park manmade obstacles like the Chilla power channel, an Army ammunition dump and rehabilitation of Tehri dam evacuees. The Eds: Vivek Menon, PS Easa and AJT Johnsingh problem was compounded by accidents owing to the railway track that passes through the area as National highway (NH 72). This study looks at WTI’s initiative in both securing the corridor as well as eliminating rail-hit incidents. B-13, Second floor, Sector - 6, NOIDA - 201 301 Uttar Pradesh, India Tel: +91 120 4143900 (30 lines) Fax: +91 120 4143933 Email: [email protected], Website: www.wti.org.in Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), is a non-profit conservation organisation, committed to help conserve nature, especially endangered species and threatened habitats, in partnership with communities and governments. Its vision is the natural heritage of India is secure. Project Team Suggested Citation: Menon, V; Easa,P.S; Johnsingh, A.J.T (2010) ‘Making Ashok Kumar Way’ - Securing the Chilla-Motichur corridor to protect elephants of Rajaji National Park. Wildlife Trust of India, New Delhi. Vivek Menon Aniruddha Mookerjee Keywords: Encroachment, Degradation, Sand mining, Corridor, Khand Gaon, P.S Easa Rehabilitation, Rajaji National Park, Anil Kumar Singh The designations of geographical entities in this publication and the A J T Johnsingh presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the authors or WTI concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries Editorial Team All rights reserved. -

No·4.-B /UHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March /6 ,2017

HIGH COURT OF UTTARAKHAND NAINITAL NOTIFICATION No. ,42 /UHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March 16 ,2017. Sri Anuj Kumar Sangal, 2nd Additional District & Sessions Judge, Dehradun is transferred and posted as R~gistrar, High Court of Utlarakhand, Nainital, vice Sri Kanwar Amninder Singh. No. 4.3 /UHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March Ib ,2017. Sri Amit Kumar Sirohi, Judge, Family Court, Nainital is repatriated and posted as Additional District & Sessions Judge, Ranikhet, District Almora, vice Sri Dharam Singh. No. 4-.It /UHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March Ic' ,2017. Sri Sahdev Singh, 2nd Additional District & Sessions Judge, Haldwani District Nainital is transferred and posted as Additional District & Sessions Judge, Kotdwar, District Pauri Garhwal, vice Sri Dhananjay Chaturvedi. No. 4 ~ /UHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March I{(; ,2017. Sri Gurubaksh Singh, Additional District & Sessions Judge, Tehri Garhwal is transferred and posted as Judge, 2nd Additional District & Sessions Judge, Dehradun, vice Sri Anuj Kumar Sangal. No·4.-b /UHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March /6 ,2017. Sri Ajay Chaudhary, Secretary-cum-Registrar, State Level Police Complaint Authority, Utlarakhand, Dehradun is repatriated and posted as 3'd Additional District & Sessions Judge, Dehradun, in the vacant Court. No. -t; "7 /UHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March /6 ,2017. Sm!. Rama Pandey, Judge, Family Court, Hardwar is repatriated and posted as FTC. /Additional District & Sessions Judge/Special Judge POCSO, Dehradun, vice Sm!. Neena Aggarwal. ~ Continued .. - 2- No..48 IUHC/Admin.Al2017 Dated: March 1(;, ,2017. Sri Pankaj Tomar, 1st Additional District & Sessions Judge, Roorkee, District Hardwar is transferred and posted as 1st Additional District & Sessions Judge, Udham Singh Nagar, vice Sri Srikant Pandey. -

6.3.3 Annual Report 2015-16.Pdf

From the Chancellor’s Desk .................................................................................. 4 From the Vice-Chancellor’s Desk ......................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 6 2. Vision & Mission ............................................................................................. 6 3. Governance ..................................................................................................... 6 • Organogram ............................................................................................ 7 • Officers of the University ..................................................................... 8 • Authorities of the University ............................................................... 8 • Members of the University.................................................................. 8 4. Accreditations ................................................................................................. 9 5. Campus and Infrastructure ........................................................................ 10 6. Faculties and Programs ............................................................................... 11 7. Distance Education Programs .................................................................... 20 8. Resources and Facilities .............................................................................. 22 9. Faculty Resources and Support Staff -

Download File (PDF 14

HIGH COURT OF UTTARAKHAND NAINITAL NOTIFICATION No. 201/UHC/Admin.A/2020 Dated: Aug.10, 2020. Shri Amit Kumar Sirohi, Judge, Family Court, Kotdwar, District Pauri Garhwal is transferred and posted as District & Sessions Judge, Tehri Garhwal in the vacant Court. Note: (a) The above transfer order will come into force with immediate effect. Note: (b) Recommendation is being sent to the Government for giving additional charge of Judge, Family Court, Kotdwar, District Pauri Garhwal to Ms. Pratibha Tiwari, Additional District & Session Judge, Kotdwar, District Pauri Garhwal in addition to her present duties. By Order of the Court, Sd/- (Hira Singh Bonal) Registrar General No.3659/UHC/Admin.A/2020 Dated: Aug. 10, 2020. Copy forwarded for information and necessary action to: - 1. Principal Secretary, Legislative, Parliamentary Affairs & Language Department, Govt. of Uttarakhand, Dehradun. 2. The Accountant General, Uttarakhand, Mahalekhakar Bhawan, Kaulagarh, Dehradun. 3. Principal Secretary, Personnel, Government of Uttarakhand, Dehradun. 4. Secretary (Law)-cum-L.R., Government of Uttarakhand, Dehradun. 5. Director, Directorate of Treasuries, Pension & Entitilements, Uttarakhand, 23, Laxmi Road, Dalanwala, Dehradun. 6. Director, Government Press, Uttarakhand, Industrial Area, Ramnagar, Roorkee- 247667, District Hardwar for Publication of the Notification in the next issue of the Gazette of Uttarakhand and also to furnish copy of Gazette to this Court. 7. All the District & Sessions Judges, Uttarakhand. 8. Principal Judge, Family Court, Dehradun and All Judges, Family Courts of State Judiciary. 9. Member Secretary, Uttarakhand State Legal Services, Authority, ADR Center, High Court Campus, Nainital. 10. Director, Uttarakhand Judicial and Legal Academy, Bhowali, Distt. Nainital. 11. All the Registrars of High Court of Uttarakhand. -

The Political Economy of Water Security in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF WATER SECURITY IN MUSSOORIE, UTTARAKHAND Final Project Report Submitted by: Nuvodita Singh In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sustainable Development Practice May 2015 0 DECLARATION This is to certify that the work that forms the basis of this project “The Political Economy of Water Security in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand” is an original work carried out by me and has not been submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree. I certify that all sources of information and data are fully acknowledged in the project report. Signature (Nuvodita Singh) Place and Date 1 Certificate This is to certify that “Nuvodita Singh” has carried out her major project in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Sustainable Development Practice on the topic “The Political Economy of Water Security in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand” during January 2015 to May 2015. The project was carried out at the “Centre for Ecology Development and Research (CEDAR), Dehradun”. The report embodies the original work of the candidate to the best of our knowledge. Date: (Signature) (Signature) Name of the External Supervisor: Name of the Internal Supervisor Dr. Devendra Chauhan Dr. Arabinda Mishra Designation: Senior Fellow Designation: Dean Name of the Organization Name of the Organization: Centre for Ecology Development TERI University and Research (CEDAR) (Signature) Dr. Shaleen Singhal Head of the Department Department of Policy Studies TERI University, New Delhi 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The last 4 months have involved a great deal of work. It has involved new challenges, new learning, new opportunities and experiences. -

In the High Court of Uttarakhand at Nainital Writ Petition (Pil) No

Bar & Bench (www.barandbench.com) RESERVED JUDGMENT IN THE HIGH COURT OF UTTARAKHAND AT NAINITAL WRIT PETITION (PIL)_ NO. 71 of 2019 Kuldeep Agarwal …….Petitioner. vs. State of Uttarakhand and others. ...Respondents Mr. Kartikey Hari Gupta, learned counsel for the petitioner. Mr. Amit Bhatt, learned Deputy Advocate General with Ms. Prabha Naithani, learned Brief Holder for the State of Uttarakhand. Mr. Piyush Garg, learned counsel for the State Bar Council of Uttarakhand. Mr. D.S. Mehta, learned counsel for the Kotdwar Bar Association. Mr. B.S. Adhikari, learned counsel for the Bar Council of India Reserved on : 31.07.2019 Delivered on: 03.09. 2019 Chronological list of cases referred: 1. (2011) 1 SCC 688 2. 366 US 82 (1961) 3. (2005) 8 SCC 771 4. (2004) 3 SCC 767 5. (2017) 5 SCC 702 6. Order in Writ Petition Criminal No.139 of 2017 dated 18.09.2017 7. AIR 2000 DELHI 266 8. (2012) 1 SCC 602 9. (2018) 3 SCC 22 10. (2004) 10 SCC 699 11. (2005) 5 SCC 294 12. (2007) 14 SCC 667 13. (2008) 9 SCC 204 14. (2008) 16 SCC 417 15. (2010) 7 SCC 263 16. AIR 1956 SCC 116 Coram: Hon’ble Ramesh Ranganathan, C.J. Hon’ble Alok Kumar Verma, J. Ramesh Ranganathan, C.J. (Oral) “From the moment that any advocate can be permitted to say that he will or will not stand between the Crown and the subject arraigned in court where he daily sits to practice, from the moment the liberties of England are at an end. -

Project : Uttarakhand Cooperative Institutional Service Board

PROJECT : UTTARAKHAND COOPERATIVE INSTITUTIONAL SERVICE BOARD. TEST DATE : 17th JUNE 2019 POST : RECRUITMENT OF JUNIOR BRANCH MANAGER (GROUP-2). FINAL ALLOTMENT DATA ALLOTED WOMEN TOTAL ALLOTED ROLL_NO REG_NO NAME DOB CATEGORY DFF PH EXS BANK ALLOTED BANK RESERVATION 200 CATEGORY CODE 1210001715 10051286 ABHILASH SUNDRIYAL 27/05/95 UR 165.75 UR B01 DISTRICT COOPERATIVE BANK LTD. DEHRADUN 2610010423 10052628 ANMOL MISHRA 03/12/95 UR 162.25 UR B04 CHAMOLI DISTRICT CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD. GOPESHWAR 2610009397 10022967 ANKIT SINGH RAUTHAN 16/01/93 UR 162.00 UR B01 DISTRICT COOPERATIVE BANK LTD. DEHRADUN 1310003401 10061327 USHA DEVI 11/10/95 UR WO 161.00 UR-WO B01 DISTRICT COOPERATIVE BANK LTD. DEHRADUN 1910003625 10060339 ROHIT BAJAJ 12/01/92 UR 159.00 UR B08 UDHAM SINGH NAGAR DISTRICT CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD. RUDRAPUR 1310003692 10051687 DISHA 15/01/95 UR WO 158.50 UR-WO B01 DISTRICT COOPERATIVE BANK LTD. DEHRADUN 2610010491 10015572 PARITOSH TRIVEDI 16/11/92 UR 158.00 UR B01 DISTRICT COOPERATIVE BANK LTD. DEHRADUN 1310003624 10058371 SONALI BHANDARI 15/11/96 UR 157.75 UR B01 DISTRICT COOPERATIVE BANK LTD. DEHRADUN 2610008230 10030204 PANKAJ NEGI 20/06/92 EBC 157.50 UR B01 DISTRICT COOPERATIVE BANK LTD. DEHRADUN 2610009557 10034049 VIVEK SOLANKI 04/12/94 UR 157.50 UR B02 HARIDWAR DISTRICT CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD. ROORKEE 1310004367 10041139 SEEMA BISHT 15/06/92 UR 157.00 UR B04 CHAMOLI DISTRICT CO-OPERATIVE BANK LTD. GOPESHWAR 2610010141 10001386 PRAVEEN KABTIYAL 12/10/89 UR 156.00 UR B05 KOTDWAR DISTRICT CO OPERATIVE BANK LTD. -

Proforma for Submission of Information by GRAPHIC ERA HILL UNIVERSITY, DEHRADUN

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI – 110002 Proforma for submission of information by GRAPHIC ERA HILL UNIVERSITY, DEHRADUN A.Legal Status 1.1 Name and Address of the University Graphic Era Hill University, Society Area, Clement Town, Dehradun 1.2 Headquarters of the University Dehradun (Uttarakhand) 1.3 Information about University a. Website______________________ a. Website :www.gehu.ac.in b. E-mail_______________________ b. E-mail :[email protected] c. Phone Nos ___________________ :[email protected] d. Fax Nos _____________________ c. Phone Nos : 09193707395 08439000729 0135-2645566 d. Fax Nos : 0135-2644025 Information about Authorities of the University a. CHANCELLOR a. Prof. (Dr.) Kamal Ghanshala Phone(office): 0135-2644025 Mobile: 09837886319 Fax Nos: e-mail : [email protected] b. VICE- CHANCELLOR b. Prof. (Dr.) Sanjay Jasola Phone(office): 0135-2645996 Mobile: 08979044410 Fax Nos: 0135-2644025 e-mail : [email protected] c. DIRECTOR CAMPUS/REGISTRAR c. Prof.(Dr.) Ajay Kumar Phone(office): 0135-2645566 Mobile: 09650544032/9193707395 Fax Nos: 0135-2644025 e-mail : [email protected] , [email protected] d. FINANCE OFFICER d. Mr. Subham Poddar Phone(office): 0135-2645566 Mobile: 09958595787 Fax Nos: 0135-2644025 e-mail : [email protected] UGC Proforma of Graphic Era Hill University, Dehradun (2019) Page 1 1.4 Date for Establishment 28-4-2011 1.5 Name of the Society / Trust promoting the Graphic Era Educational Society University ( Information may be provided in the Dehradun. following format) -

Ssr Part-I Doon University, Dehradun

SSR PART-I DOON UNIVERSITY, DEHRADUN SSR PART-I DOON UNIVERSITY, DEHRADUN Contents PREFACE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 6 PART -1 PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY 7 17 CRITERION- I (CURRICULAR ASPECTS) 18 31 1.1. Curriculum Design and Development 18 24 1.2. Academic Flexibility 24 29 1.3 Curriculum Enrichment: 29 30 1.4 Feedback System: 31 31 CRITERION –II (TEACHING, LEARNING AND EVALUATION) 32 51 2.1Student Enrolment and Profile 32 34 2.2. Catering to Student Diversity 34 36 2.3 Teaching-Learning Process 37 42 2.4. Teacher Quality: 42 45 2.5. Evaluation Process and Reforms 46 49 2.6. Student Performance and Learning Outcomes 49 51 CRITERIA III: (RESEARCH, CONSULTANCY AND EXTENSION) 52 117 3.1. Promotion of Research 52 60 3.2 Resource Mobilization for Research 60 69 3.3 Research Facilities: 69 71 3.4. Research Publications and Awards 71 110 3.5. Consultancy 110 112 3.6 Extension Activities and Institutional Social Responsibility (ISR) 112 116 3.7. Collaboration 116 117 CRITERIA IV- (INFRASTRUCTURE AND LEARNING RESOURCES) 118 136 4.1. Physical facilities 118 123 4.2. Library as Learning Resource 123 130 4.3. IT Infrastructure 130 135 4.4. Maintenence of Campus Facilities 135 136 CRITERIA- V (STUDENT SUPPORT AND PROGRESSION) 137 154 5.1. Student Mentoring and Support 137 146 5.2. Student Progression 146 150 5.3. Student Participation and Activities 150 154 CRITERIA VI: (GOVERNANCE, LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT) 155 177 6.1. Institutional Vision and Leadership 155 165 6.2. Strategy Development and Deployment 165 171 6.3. -

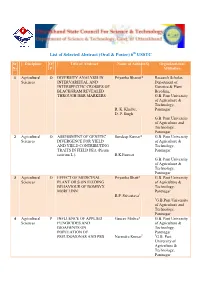

List of Selected Abstrac List of Selected Abstract

List of Selected Abstract (Oral & Poster) 6 th USSTC Sr. Discipline O/ Title of Abstract Name of Author(S) Organizational No P Affiliation . 1 Agricultural O DIVERSITY ANALYSIS IN Priyanka Bhareti* Research Scholar, Sciences INTERVARIETAL AND Department of INTERSPECIFIC CROSSES OF Genetics & Plant BLACKGRAM REVEALED Breeding, THROUGH ISSR MARKERS G.B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, R. K. Khulbe, Pantnagar D. P. Singh G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar 2 Agricultural O ASSESSMENT OF GENETIC Sundeep Kumar* G.B. Pant University Sciences DIVERGENCE FOR YIELD of Agriculture & AND YIELD CONTRIBUTING Technology, TRAITS IN FIELD PEA (Pisum Pantnagar sativum L.). R.K.Panwar G.B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, Pantnagar 3 Agricultural O EFFECT OF MEDICINAL Priyanka Bhatt* G.B. Pant University Sciences PLANT OILS ON FEEDING of Agriculture & BEHAVIOUR OF BOMBYX Technology, MORI LINN. Pantnagar R.P. Srivastava 1 1G.B.Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Pantnagar 4 Agricultural P INFLUENCE OF APPLIED Gaurav Mishra* G.B. Pant University Sciences FUNGICIDES AND of Agriculture & BIOAGENTS ON Technology, POPULATION OF Pantnagar PSEUDOMONAS AND PSB Narendra Kumar 1 1G.B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, Pantnagar 5 Agricultural P BIOEFFICACY OF PLANT B.S. Kharayat* College of Sciences EXTRACTS AGAINST Agriculture, ZONATE LEAF SPOT OF G.B. Pant University SORGHUM CAUSED by of Agriculture & Gleocercospora sorghi Bain & Y. Singh Technology, Edgerton Pantnagar G.B. Pant University of Agriculture & Technology, Pantnagar 6 Agricultural O BIO-EFFICACY OF Akshita Banga* Department of Sciences TEMBOTRIONE 42% SC Agronomy, (LAUDIS 42 SC) + G.B. Pant University SURFACTANT AGAINST of Agriculture & MIXED WEED COMPLEX IN Technology, MAIZE V.P. -

A Study of Utilization of Media for Traffic Awareness

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 04, 2020 A STUDY OF UTILIZATION OF MEDIA FOR TRAFFIC AWARENESS Ritesh Chaudhary1, Shobha Chaudhary2 1School of Media, Journalism & Film Making Himgiri Zee University, Dehradun Email: [email protected], Mobile: 9936825689 2Department of Mass Communication Khawaja Moinuddin Chishti Language University, Lucknow Email: [email protected] Mobile: 91-8419034537 ABSTRACT Among the basic needs of the people, after bread, clothes and houses, other essential things are electricity, water and roads. These are the needs without which people's life would be like living in the primitive world. In all of these, there is such a system of roads, through which a person tries to emerge himself as a big competitor in the stream of development, because the movement itself leads to the development ladder, otherwise sitting at home can lead to any development Cannot move forward. Traffic safety rules were made to make the road system strong and safe. The role of media becomes important for maintaining this traffic safety and their compliance, because media is called representative of general public. Media is also known as the bridge between the government and the common man. The role of the media also becomes important because it works with the neutrality of a law and studies it and presents it to the people. The study presented studies the role of media for traffic awareness. Content analysis and survey method have been adopted in this study. Through the study, an attempt has been made to find out how much and why people follow traffic rules.