Dvorak Piano Quintet Op. 81 Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spohr and Schumann

SPOHR AND SCHUMANN by Keith Warsop OR MOST PEOPLE the link between Louis Spohr and Robert Schumann is limited to the latter's negative criticism of the Historrcai Symphony. In fact, the two musicians had a high regard for each other's compositions even though they each sometimes had reservations about particular aspects of certain individual works. Unfortunately, Spohr broke off his memoirs when he reached June 1838 shortly before he and Schumann met for the first time so we do not have his considered thoughts about Schumann's music in general. However, in the section of the memoirs added by his second wife, Marianne, after Spohr's death, she records that after the stay in Carlsbad detailed by Spohr in the last paragraphs he wrote down himself, they stopped in Leipzig on their way home. There, Marianne continues, "it was a source of great pleasure to him to make the long-desired acquaintance of Robert Schumann who, though in other respects exceedingly quiet and reserved, yet evinced his admiration of Spohr with great warmth and gratified him by the performanee of several of his interesting fantasias. " The two composers had, however, been in touch a few months before through the agency of a third composer, Felix Mendelssohn. On 24th November 1836, Mendelssohn wrote to Spohr requesting a song for inclusion in the wedding album of his new bride, Cdcilie Jeanrenaud, and on l3th December wrote again to thank Spohr for the song 'Was mir wohl tibrig bliebe', WoO96 (later included by Spohr as No.5 of his Op.139 Lieder collection). -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 Johannes Brahms ohannes Brahms was 29 years old in 1862, seated at the other piano. Ironically, critics Jwhen he embarked on this seminal mas- now complained that the work lacked the terpiece of the chamber-music repertoire, sort of warmth that string instruments would though the work would not reach its final have provided — the opposite of Joachim’s form as his Piano Quintet until two years objection. Unlike the original string-quintet later. He was no beginner in chamber music version, which Brahms burned, the piano when he began this project. He had already duet was published — and is still performed written dozens of ensemble works before and appreciated — as his Op. 34bis. he dared to publish one, his B-major Piano By this time, however, Brahms must have Trio (Op. 8) of 1853–54. Among those early, grown convinced of the musical merits of his unpublished chamber pieces were 20-odd material and, with some coaxing from his string quartets, all of which he consigned friend Clara Schumann, he gave the piece to destruction prior to finally publishing his one more try, incorporating the most idiom- three mature works in that classic genre in atic aspects of both versions. The resulting the 1870s. In truth, he did get some use out Piano Quintet, the composer’s only essay of those early quartets — to paper the walls in that genre (and no wonder, after all that and ceilings of his apartment. -

Copyright by Erica France Manzo 2003

Copyright by Erica France Manzo 2003 The Treatise Committee for Erica France Manzo Certifies that this is the approved version of the following treatise: PIANO QUINTET IN Eb MAJOR, OP. 44 BY ROBERT SCHUMANN: TRANSCRIBED FOR CLARINET QUARTET AND PIANO Committee: Elizabeth B. Crist, Co-Supervisor Richard L. MacDowell, Co-Supervisor Lorenzo F. Candelaria Rebecca Henderson Kristin W. Jensen Chandra L. Muller PIANO QUINTET IN Eb MAJOR, OP. 44 BY ROBERT SCHUMANN: TRANSCRIBED FOR CLARINET QUARTET AND PIANO by Erica France Manzo, B.M., M.M. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2003 PIANO QUINTET IN Eb MAJOR, OP. 44 BY ROBERT SCHUMANN: TRANSCRIBED FOR CLARINET QUARTET AND PIANO Publication No._____________ Erica France Manzo, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2003 Supervisors: Elizabeth B. Crist and Richard L. MacDowell Few substantial works exist for clarinet quartet and piano, even though such pieces would be of great practical use to advanced students. Piano quintets transcribed for four clarinets and piano would undoubtedly retain musical value and not compromise the masterworks involved. This treatise presents an arrangement of Robert Schumann’s Piano Quintet in Eb, Op. 44, transcribed for three Bb soprano clarinets and one Bb bass clarinet. The first chapter includes a historical background of chamber music literature containing clarinet quartet as well a justification for both the need and purpose for such a transcription. Chapter 2 contains the history of the piano quintet genre and an overview of Schumann’s Piano Quintet in Eb, Op. -

Progressive Tonality in the Finale of the Piano Quintet, Ope 44 of Robert Schumann

Progressive Tonality in the Finale of the Piano Quintet, Ope 44 of Robert Schumann John C. Nelson Through the nineteenth century and even into the twentieth, when one thinks of tonality in instrumental music, tonal closure is assumed. That is, a work or a movement of a larger work begins and ends in the same key. Simple? Certainly. That this is not the case with, among other genres, opera in the nineteenth century is a well-documented fact. In the Classical operas of Haydn and Mozart and the early Romantic operas of Rossini, tonal closure over an entire opera or at least within significant sections such as finales was the norm. However, by the time of Donizetti operas rarely ended in the key in which they opened and in act finales or other large scenes, places where Mozartean tonal closure might seem to have been an idea worth continuing, progressive tonality was the norm. Apparently, the structural unity brought about by tonal closure was not felt to be necessary: dramatic unity ofplot was sufficient. One particularly significant exception to the rule of tonal closure in instrumental music is the finale ofRobert Schumann's Piano Quintet, Op. 44. This work is a product of his extremely fertile chamber music 42 Indiana Theory Review Vol. 13/1 year of 1842, a year which also saw the composition of the three string quartets of Op. 41 and the Piano Quartet, Op. 47. This finale, unique in his instrumental music, is tonally progressive, opening in G minor and reaching its ultimate tonic of E-flat only at the return of the B episode, and even here its finality is challenged severely. -

R Obert Schum Ann's Piano Concerto in AM Inor, Op. 54

Order Number 0S0T795 Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54: A stemmatic analysis of the sources Kang, Mahn-Hee, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 U MI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 ROBERT SCHUMANN S PIANO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, OP. 54: A STEMMATIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mahn-Hee Kang, B.M., M.M., M.M. The Ohio State University 1992 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Lois Rosow Charles Atkinson - Adviser Burdette Green School of Music Copyright by Mahn-Hee Kang 1992 In Memory of Malcolm Frager (1935-1991) 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the late Malcolm Frager, who not only enthusiastically encouraged me In my research but also gave me access to source materials that were otherwise unavailable or hard to find. He gave me an original exemplar of Carl Relnecke's edition of the concerto, and provided me with photocopies of Schumann's autograph manuscript, the wind parts from the first printed edition, and Clara Schumann's "Instructive edition." Mr. Frager. who was the first to publish information on the textual content of the autograph manuscript, made It possible for me to use his discoveries as a foundation for further research. I am deeply grateful to him for giving me this opportunity. I express sincere appreciation to my adviser Dr. Lois Rosow for her patience, understanding, guidance, and insight throughout the research. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

Tesla Quartet

TESLA QUARTET R O S S S NYD E R & M I C H E L L E L IE, V I O L I N S – E D W I N K APLAN , V I O L A – S E R A F I M S MIGELSKIY, CELLO 412.952.8676 • [email protected] • www.teslaquartet.com Repertoire * Tesla Quartet commission/premiere String Quartets Elliott Bark Tango Suite Bartók String Quartet No.2, Sz.67 (Op.17) String Quartet No.4, Sz.91 String Quartet No.6, Sz.114 Romanian Folk Dances (arr. Snyder) Beethoven String Quartet in G, Op.18 No.2 String Quartet in B-flat, Op.18 No.6 String Quartet in F, Op.59 No.1 String Quartet in C, Op.59 No.3 String Quartet in F, Op.135 Matthew Browne Great Danger, Keep Out* Brett Dean Eclipse Debussy String Quartet in G minor, Op.10 Dutilleux Ainsi la nuit Dvořák String Quartet No.12 in F, Op.96, “American” String Quartet No.14 in A-flat, Op.105 Erberk Eryılmaz Miniatures Set No.4 Haydn String Quartet in C, Op.20 No.2 String Quartet in D, Op.20 No.4 String Quartet in B minor, Op.33 No.1 String Quartet in G, Op.33 No.5 String Quartet in G, Op.76 No.1 String Quartet in B-flat, Op.76 No.4, “Sunrise” String Quartet in D, Op.76 No.5 Janáček String Quartet No.1, “The Kreutzer Sonata” TESLA QUARTET R O S S S NYD E R & M I C H E L L E L IE, V I O L I N S – E D W I N K APLAN , V I O L A – S E R A F I M S MIGELSKIY, CELLO 412.952.8676 • [email protected] • www.teslaquartet.com Daniel Kellogg “Soft Sleep Shall Contain You” Ligeti Andante and Allegretto Gabriel Lubell A Study of Luminous Objects: String Quartet No.1 Albéric Magnard String Quartet, Op.16 Mendelssohn String Quartet in A minor, Op.13 -

Robert Schumann 1810–1856

Jodi Levitz Carla Moore The Benvenue Fortepiano Trio 2 Robert Schumann 1810–1856 Märchenbilder Op.113* 1 I. Nicht schnell 3.29 2 II. Lebhaft 3.58 3 III. Rasch 2.32 4 IV. Langsam 5.26 Fünf Stücke im Volkston Op.102 † 5 I. Mit Humor 3.05 6 II. Langsam 3.21 7 III. Nicht schnell 4.13 8 IV. Nicht zu rasch 1.53 9 V. Stark und markiert 3.00 Piano Quintet in E flat Op.44° 10 I. Allegro brillante 9.04 11 II. In modo d’un marcia 7.50 12 III. Scherzo 4.51 13 IV. Allegro ma non troppo 7.06 59.48 The Benvenue Fortepiano Trio on period instruments * † ° Eric Zivian fortepiano (Franz Rausch, Vienna, 1841) ° Monica Huggett violin (Dutch [Cuypers School], circa 1770) † ° Tanya Tomkins cello (Joseph Panormo, London, 1811) *°Jodi Levitz viola (Andrea Ghisalberti, Parma, 1729) ° Carla Moore violin (Johann Georg Thir, Vienna, 1754) 3 When Robert Schumann finally married Clara Wieck on 12 September 1840, it marked the end of a long battle with Clara’s father, Friedrich Wieck, who considered the 30-year-old composer unfit for her. As Wieck’s arguments fell away and it became clear that the young lovers would soon be able to marry, Schumann entered an extraordinary phase of compositional productivity. During 1840 and into 1841 – known as the composer’s Liederjahr or ‘year of song’ – he composed no fewer than 125 Lieder, casting them off at white heat, sometimes at the rate of two a day. This prodigious activity continued into the next year, when he turned his mind to the orchestra, composing the First Symphony and the original version of the Fourth, along with the Overture, Scherzo and Finale and the piano Phantasie, which was to become the first movement of the Piano Concerto a few years later. -

Musicians from Marlboro Joseph Lin, Violin Francisco Fullana, Violin Pei-Ling Lin, Viola Ahrim Kim, Cello Jay Campbell, Cello Zoltán Fejévári, Piano

THE GERTRUDE CLARKE WHITTALL FOUNDATION iN tHE LIBRARY oF CONGRESS MUSICIANS FROM MARLBORO JOSEPH LIN, VIOLIN FRANCISCO FULLANA, VIOLIN PEI-LING LIN, vIOLA AHRIM KIM, cELLO JAY CAMPBELL, cELLO zOLTÁn FEJÉVÁRI, PIANO Friday, May 6, 2016 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building In 1935 Gertrude Clarke Whittall gave the Library of Congress five Stradivari instruments and three years later built the Whittall Pavilion in which to house them. The GERTRUDE CLARKE WHITTALL FOUNDATION was established to provide for the maintenance of the instruments, to support concerts (especially those that feature her donated instruments), and to add to the collection of rare manuscripts that she had additionally given to the Library. This concert is co-presented with THE BILL AND MARY MEYER CONCERT SERIES FREER GALLERY OF ART AND ARTHUR M. SACKLER GALLERY PART OF NATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC MONTH & EUROPEAN MONTH OF CULTURE PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE EMBASSY OF FINLAND & THE DELEGATION OF THE EUROPEAN UNION TO THE UNITED STATES Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. -

Liner Notes by Patrick Castillo and Andrew Goldstein

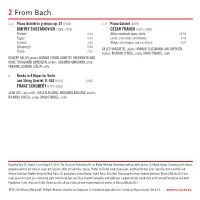

2 From Bach 1–5 Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) 7–9 Piano Quintet (1879) DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) CÉSAR FRANCK (1822–1890) Prelude 4:34 Molto moderato quasi lento 14:50 Fugue 9:33 Lento, con molto sentimento 9:49 Scherzo 3:25 Allegro non troppo, ma con fuoco 8:57 Intermezzo 5:50 GILLES VONSATTEL, piano; ARNAUD SUSSMANN, IAN SWENSEN, Finale 7:22 violins; RICHARD O’NEILL, viola; DAVID FINCKEL, cello GILBERT KALISH, piano; DANISH STRING QUARTET: FREDERIK ØLAND, RUNE TONSGAARD SØRENSEN, violins; ASBJØRN NØRGAARD, viola; FREDRIK SCHØYEN SJÖLIN, cello 6 Rondo in A Major for Violin and String Quartet, D. 438 (1816) 14:01 FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797–1828) SEAN LEE, solo violin; JORJA FLEEZANIS, BENJAMIN BEILMAN, violins; RICHARD O’NEILL, viola; DAVID FINCKEL, cello Recorded July 21, August 3, and August 9, 2013, The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton. Recording producer and engineer: Da-Hong Seetoo. Steinway grand pianos provided courtesy of ProPiano. Cover art: Imprint, 2006, by Sebastian Spreng. Photos by Tristan Cook, Diana Lake, and Brian Benton. Liner notes by Patrick Castillo and Andrew Goldstein. Booklet design by Nick Stone. CD production: Jerome Bunke, Digital Force, New York. Production Assistant: Andrew Goldstein. Music@Menlo 2013 was made possible in part by a leadership grant from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation with additional support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and Koret Foundation Funds. American Public Media was the official radio and new-media broadcast partner of Music@Menlo 2013. © 2013 Music@Menlo LIVE. All Rights Reserved. Unauthorized Duplication Is a Violation of Applicable Laws. -

Chamber Music Repertoire Trios

Rubén Rengel January 2020 Chamber Music Repertoire Trios Beethoven , Piano Trio No. 7 in B-lat Major “Archduke”, Op. 97 Beethoven , String Trio in G Major, Op. 9 No. 1 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 1 in B Major, Op. 8 Brahms , Piano Trio No. 2 in C Major, Op. 87 Brahms , Horn Trio E-lat Major, Op. 40 U. Choe, Piano Trio ‘Looper’ Haydn, P iano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 Haydn, Piano Trio in C Major, Hob. XV: 27 Mendelssohn , Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 Mendelssohn, Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor, Op. 66 Mozart , Divertimento in E-lat Major, K. 563 Rachmaninoff, Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor Ravel, Piano Trio in A minor Saint-Saëns , Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 18 Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 Stravinsky , L’Histoire du Soldat Tchaikovsky, Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 Quartets Arensky , Quartet for Violin, Viola and Two Cellos in A minor, Op. 35 No. 2 (Viola) Bartok, String Quartet No. 1 in A minor, Sz. 40 Bartok , String Quartet No. 5, Sz. 102, BB 110 Beethoven , Piano Quartet in E-lat Major, Op. 16 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 4 in C minor, Op. 18 No. 4 Beethoven , String Quartet No. 5 in A Major, Op. 18 No. 5 Beethoven, String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Op. 59 No. 2 Borodin , String Quartet No. 2 in D Major Debussy , String Quartet in G Major, Op. 10 (Viola) Dvorak, Piano Quartet No. 2 in E-lat Major, Op. -

Béla Bart´Ok's Piano Quintet

BÉLA BARTÓK’S PIANO QUINTET Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Garreffa, Andrea Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 08/10/2021 04:43:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195851 BELA´ BARTOK’S´ PIANO QUINTET by Andrea Garreffa Copyright c Andrea Garreffa 2010 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the doc- ument prepared by Andrea Garreffa entitled B´ela Bart´ok’s Piano Quintet and rec- ommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date: 6/7/2010 Paula Fan Date: 6/7/2010 Tannis Gibson Date: 6/7/2010 Lisa Zdechlik Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hearby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. Date: 6/7/2010 Director: Paula Fan 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This document has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library.