A Time of Greeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Download File

Brevard Live August 2015 - 1 2 - Brevard Live August 2015 Brevard Live August 2015 - 3 4 - Brevard Live August 2015 Brevard Live August 2015 - 5 6 - Brevard Live August 2015 Contents August 2015 FEATURES LAURA JANE GRACE While at Bonnaroo Matthew Bretz did Columns BMA-WINNERS not just listen to many artists’ perfor- Charles Van Riper The music fans have spoken: FunDecid- mances, he also had the opportunity to 22 Political Satire ed is Brevard’s Entertainer of the Year talk with them. Laura Jame Grace of 2015. Meet the band members of this Against Me was one of his interview Calendars self-proclaimed “tourist band” and find partners. Live Entertainment, out who else went home with a BMA Page 18 25 Concerts, Festivals trophy. Page 12 ROBERT TRUJILLO Outta Space He was the bassist for the Suicidal Ten- 30 by Jared Campbell 80s IN THE PARK dencies, the Infectious Grooves. He This year’s roster features Lita Ford, toured with Ozzie, and played with the Local Download Slaughter, Asia featuring John Payne, Black Label society. Then in 2003 Tru- by Andy Harrington LA Guns, Kip Winger, Firehouse, Bullet 33 jillo joined Metallica and that’s where Local Music Scene Boys, MASS, Autograph, Femme Fatal, he’s been ever since. Nova Rex, Kenny McGee, and more. Page 20 Flori-duh! Page 15 36 by Charles Knight MAKING THE SCENE “WEIRD AL” YANKOVIC For the past five years Steagles has been The Dope Doctor “Weird Al” is the biggest-selling comedy offering more than the Best Cheesesteak 38 Luis Delgado, CAP recording artist in history. -

“A Moving, Enchanting Story of Love and Loss. Amanda Wen Takes Read- Ers on an Adventure That Weaves Past and Present Together

“A moving, enchanting story of love and loss. Amanda Wen takes read- ers on an adventure that weaves past and present together in a beautiful tapestry of skillful storytelling. I was blown away by this book and its timeless message.” Heidi CHiavaroli, Carol Award–winning author of Freedom’s Ring and Te Tea Chest “Amanda Wen seamlessly blends the historical and the contemporary in this lyrical debut. From Annabelle, a courageous young woman building a life on the Kansas frontier, to Sloane, a museum curator searching for answers within the pages of a diary penned over one hundred years ago, Roots of Wood and Stone spans generations in a brilliantly rendered nar- rative that explores the heart behind the places we call home.” amanda Barratt, author of Te White Rose Resists and My Dearest Dietrich “Compelling. Rich. Winding through past and present and linking them in surprising ways, Wen’s debut novel captures the legacy of a his- toric farmhouse and all the people who’ve made their lives there. I was rooting for Sloane out of the gate, and my heart went up and down with her story until the well-drawn conclusion. Wen writes with warmth and a delightful voice about heritage, family, and the nature of what’s truly important.” Joanna davidson Politano, author of Te Love Note “Now and then I am fortunate enough to read a book that so thoroughly captures me that I forget I’m reading. It’s rare, but when it happens it feels a whole lot like magic. Amanda Wen has written such a novel. -

A Concept Album

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Honors Program Contracts Honors Program Spring 2020 The Power of Protest Music: A Concept Album Matthew Patterson Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_component Part of the Music Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Matthew, "The Power of Protest Music: A Concept Album" (2020). Honors Program Contracts. 20. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/honors_component/20 This Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Program Contracts by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Matthew Patterson Dr. Anne Flaherty and Dr. Laura Pruett Music and Politics FAA/POL3171 6 May 2020 The Power of Protest Music: A Concept Album Introduction: This semester, I decided to create an honors contract for one of my favorite classes offered at Merrimack, Music and Politics. Both music and politics are two of my biggest interests, so I felt that this class would allow me to create a very unique final project. For my project, I decided to create my own political concept album that would analyze the role of music in certain social and political movements. Inspired by old vinyl records, this curation will contain 12 songs that are divided evenly on each side of the record. Side A will contain six songs that are considered anthems of the Civil Rights Movement, while Side B will contain six songs that are considered anthems for the Black Lives Matter Movement. -

Indancespring 2021

SPRING 2021 inDISCOURSE +dance DIALOGUE TO UNIFY, STRENGTHEN + AMPLIFY P.06 Fresh Meat Productions P.32 Sharing with Strength P.44 Ad Infinitum Identities MEMBERSHIP Dancers’ Group – publisher of In Dance – provides resources to artists, the dance community, and audiences through programs and services that are as collaborative and WELCOME innovative as the creative process. CONTENTS Dancers’ Group has extended all memberships through June 2021. If you’re interested in becoming a new member, consider joining at I'VE BEEN READING, READING, READING. our free Community level. It’s a lovely part of my job. I get to read grant pro- Visit dancersgroup.org for more information and resources. posals, budgets (numbers tell a story, too), research studies, emails and numerous articles featured in In Dance —finding comfort and inspiration as I read JOIN in my spare time. dancersgroup.org My post-work reading is eclectic and is made up of consuming features in various online publica- tions. Also I love fiction books —like Bryan Washing- ton’s beautiful novel called Memorial. And I’ve been SUBMIT reading lots of NY Times features on artists. Through Performances to the these pieces I’m being introduced to live-treasures. Community Calendar They’ve become my weekly, sometimes daily, inspire-pleasure. Dancers’ Group promotes performance Here’s a highlight of those I’ve been learning about. I’ve fallen for the artist listings in our online performance calendar, and emailed to over Lorraine O’Grady whose newspaper poems from 1977 are stunning visual dances. 1,700 members. The artist Roni Horn has led me to appreciate the word “acclimatize”—I want to figure out how to use it in a sentence. -

Billboard Magazine

11.02.2013 billboard.com billboard.biz ATLANTIC'S SUPER BOWL PLAY Doritos Partnership Drives Synchs NEW LIFE FOR RHAPSODY Telecom Bundles Drive 13* Scale FILM/TV MUSIC CONFERENCE HELLO, SIA 4. IL r!1 ti 14,1 410 $6 99US $8.99CAM 4 2> 7 896 47205 9 UK £5.50 "ONE OF THE BESTWorldMags.net"THE ARRIVAL OF "ONE OF THE MOST STRIKING STORIES IN POP" A NEW KIND OF STAR " ARTISTS IN R&B " -- ROLLING STONE -- ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY -- NEW YORK TIMES * * * * * * * * * * taylor swift lorde the weeknd *IDE / BILLBOARD TOP 200 ALBUMS a1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP ROCK ALBUMS / BILLBOARD TOP R&B ALBUMS siSINt "I KNEW YOU WERE TROUBLE" #1 SINGLE "ROYALS"' "LIVE FOR" Source: Billboard Hot Digital Songs Source: Billboard Hot too Songs Source: rTunes / Top R&B / Soul Song's (8.20.13) "THIS MIGHT BE THE MOST -AN AMALGAM OF EVERYTHING "THE BIGGEST STORY IN COUNTRY INVITING POP RECORD OF 20f3 " YOU'D WANT FROM A NEW MUSIC THIS YEAR [201.91 IS MOST -- LA TIMES BLACK SABBATH ALBUM" -- NME CERTAINLY FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE" * * -- THE ARGUS LEADER * * * * * ariana grande black sabbath florida #1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP 200 ALBUMS / BILLBOARD TOP 200 ALBUMS #1 SINGLE "THE WAY"" "GOD IS DEAD" georgia line #1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP COUNTRY ALBUMS #1 SINGLE "CRUISE"` -.+111P. Source: iTures / Top Singles (3.25.r3) Source: Mechabase Mainstream Rock (5.24,3) "...HELLA-COOL DEBUT" `AN ARTISTIC TOUR DE FORCE THAT ROWLAND STEPS OUT WITH PEOPLE FURTHERS THE POTENT/AL SHOWN SURE FOOTING, A GIRL -NEXT * * * * ON GROUP'SAWARD-WINNING DEBUT. " DOOR WHO BELONGS ON TOP" -- THE ASSOCIATED PRESS - SPIN of monsters * * * * * and men the band perry kelly rowland *1DEBI./ BILLBOARD TOP ROCK ALBUMS #1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP COUNTRY ALBUMS / BILLBOARD TOP R&B ALBUMS "LITTLE TALKS" #1 SINGLE "BETTER DIG TWO"` "KISSES DOWN LOW" *t- IN V ' Atk 4446 A Irrirffei Source: Billboard Country Airplay republic for your grammy® consideration WorldMags.net WorldMags.net THIS WEEK Volume 125 [ No. -

Judithe Hernández Interviewed by Karen Mary Davalos on September 26, 2009, and July 14, 2010

CSRC ORAL HISTORIES SERIES NO. 13, DECEMBER 2013 JUDITHE HERNÁNDEZ INTERVIEWED BY KAREN MARY DAVALOS ON SEPTEMBER 26, 2009, AND JULY 14, 2010 Judithe Hernández is a Los Angeles-based artist first recognized as a muralist and now widely known for her works in pastel. A member of Los Four for ten years, she participated in ten major exhibitions with the art collective. She has exhibited internationally, and her work has been acquired by private collectors and major institutions, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, the El Paso Museum of Art, and the Bank of America collection in New York. She is the recipient of a COLA fellowship from the city of Los Angeles, and she was selected by the Los Angeles Transit Authority to create the art for the Santa Monica Metro station, scheduled to open in 2016. Karen Mary Davalos is chair and professor of Chicana/o studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Her research interests encompass representational practices, including art exhibition and collection; vernacular performance; spirituality; feminist scholarship and epistemologies; and oral history. Among her publications are Yolanda M. López (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2008); “The Mexican Museum of San Francisco: A Brief History with an Interpretive Analysis,” in The Mexican Museum of San Francisco Papers, 1971–2006 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2010); and Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora (University of New Mexico Press, 2001). This interview was conducted as part of the L.A. Xicano project. Preferred citation: Judithe Hernández, interview with Karen Davalos, on September 26, 2009, and July 14, 2010, Los Angeles, California. -

Golden Gate Grooves

THE GOLDEN GATE BLUES SOCIETY QUARTERLY Issue 13, April 2012 GOLDEN GATE GROOVES MY EXPERIENCE AT THE 2012 INTERNATIONAL BLUES CHALLENGE: MEMPHIS by Paula Harris Paula Harris and Blu Gruv won the band portion of The Golden Gate Blues Society's International Blues Challenge in November 2011 and competed as one of 110 bands in Memphis in February 2012. The following is Paula's personal story. Photography by Rob Smith of RobSmithPhotos.com January 31, 2012 - Tuesday nervousness of why we were in Memphis, and the burden of feeling like we needed to show well for our Got up at 4 a.m. to drive hubby to SFO for his 8am flight. Golden Gate Blues Society lifted off me. A calm feeling of So I sat at the airport until our flight was "supposed" to peace came over me and I knew that we would do our take off at 10:30 a.m. But after sitting on the plane for an best and that would be enough no matter what the hour, they had us deplane and we tried to reschedule outcome was. another flight. We ended up getting back on the same plane and finally taking off around 1 p.m. We got to February 1 - Wednesday Dallas only to find that our original seat assignments had Got up early (6 a.m.) to make sure that the promotional been cancelled (gasp of horror!). Thank God the plane material we wanted to pass out had made it to Memphis. was nearly empty, so we all had our own rows from After going round a bit with UPS, we got everything Dallas to Memphis. -

Blanchard 46 ‘We Are All Humans’ by AARON COHEN Trumpeter Terence Blanchard’S New Release Is a Concert Disc That Chronicles His Dynamic Band, the E-Collective

JULY 2018 VOLUME 85 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Sales Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin Tolleson; Philadelphia: David Adler, Shaun Brady, Eric Fine; San Francisco: Mars Breslow, Forrest Bryant, Clayton Call, Yoshi Kato; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Tampa Bay: Philip Booth; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: Greg Buium, James Hale, Diane Moon; Denmark: Jan Persson; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Detlev Schilke, Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Brian Priestley; Japan: Kiyoshi Koyama; Portugal: Antonio Rubio; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Ohiou1243969955.Pdf (227.06

Journey to the East: Essays A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Stephen David Grover June 2009 © 2009 Stephen David Grover. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Journey to the East: Essays by STEPHEN DAVID GROVER has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Dinty W. Moore Professor of English Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GROVER, STEPHEN DAVID, M.A., June 2009, English Journey to the East: Essays (76 pp.) Director of thesis: Dinty W. Moore This thesis is a collection of seven personal essays written by the author and headed by a critical introduction. The introduction presents a common theme among the essays—that they represent a “journey to the East”—and points out the function of memory in the essays and the necessity for some distance between the speaker and the protagonist in each, even though those two may in fact be the same person. Such distance, the author claims, allows valuable discoveries to be made and justifies an otherwise purely egotistical venture. The introduction also expresses the author’s desire that his essays promote empathy—between author and reader, between reader and the world, and between the reader and the reader’s self. Approved: _____________________________________________________________ Dinty W. Moore Professor of English 4 DEDICATION For Jon 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express thanks for all those who helped me put this thesis together, including those who participated in workshops with me and offered their sincere advice, those who read and responded to these essays in their free time, and those who offered encouragement and advice outside the express act of writing—among others: Joey, Liz, Holly, Catherine, Zach, and Diana. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title +44 3 Doors Down 5 Stairsteps, The When Your Heart Stops Live For Today Ooh Child Beating Loser 50 Cent 10 Years Road I'm On, The Candy Shop Beautiful When I'm Gone Disco Inferno Through The Iris When You're Young In Da Club Wasteland 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Just A Lil' Bit 10,000 Maniacs Landing In London P.I.M.P. (Remix) Because The Night 3 Of Hearts Piggy Bank Candy Everybody Wants Arizona Rain Window Shopper Like The Weather Love Is Enough 50 Cent & Eminem & Adam Levine These Are Days 30 Seconds To Mars My Life 10CC Closer To The Edge My Life (Clean Version) Dreadlock Holiday Kill, The 50 Cent & Mobb Deep I'm Not In Love 311 Outta Control 112 Amber 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Peaches & Cream Beyond The Gray Sky 21 Questions U Already Know Creatures (For A While) 50 Cent & Ne-Yo 1910 Fruitgum Co. Don't Tread On Me Baby By Me Simon Says Hey You 50 Cent & Olivia 1975, The I'll Be Here Awhile Best Friend Chocolate Lovesong 50 Cent & Snoop Dogg & Young 2 Pac You Wouldn't Believe Jeezy California Love 38 Special Major Distribution (Clean Changes Hold On Loosely Version) Dear Mama Second Chance 5th Dimension, The How Do You Want It 3LW Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) 2 Pistols & Ray J No More Aquariuslet The Sunshine You Know Me 3OH!3 In 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Trust Me Last Night I Didn't Get To She Got It StarStrukk Sleep At All 21 Demands 3OH!3 & Ke$ha One Less Bell To Answer Give Me A Minute My First Kiss Stoned Soul Picnic 3 Doors Down 3OH!3 & Neon Hitch Up Up & Away Away From The Sun Follow Me Down Wedding Bell Blues Be Like That 3T 6 Tre G Behind Those Eyes Anything Fresh Citizen Soldier 4 Non Blondes 702 Duck & Run What's Up I Still Love You Here By Me 4 P.M. -

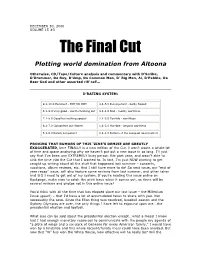

The Final Cut Plotting World Domination from Altoona

DECEMBER 30, 2000 VOLUME 15 #3 The Final Cut Plotting world domination from Altoona Otherwise, CD/Tape/Culture analysis and commentary with D’Scribe, D’Drummer, Da Boy, D’Ump, Da Common Man, D’ Big Man, Al, D’Pebble, Da Beer God and other assorted riff raff... D'RATING SYSTEM: 9.1-10.0 Excellent - BUY OR DIE! 4.1-5.0 Incompetent - badly flawed 8.1-9.0 Very good - worth checking out 3.1-4.0 Bad - mostly worthless 7.1-8.0 Good but nothing special 2.1-3.0 Terrible - worthless 6.1-7.0 Competent but flawed 1.1-2.0 Horrible - beyond worthless 5.1-6.0 Barely competent 0.1-1.0 Bottom of the cesspool abomination! PROVING THAT RUMORS OF THIS ‘ZINE’S DEMISE ARE GREATLY EXAGGERATED, here FINALLY is a new edition of the Cut. I won’t waste a whole lot of time and space analyzing why we haven’t put out a new issue in so long. I’ll just say that I’ve been one EXTREMELY busy person this past year, and wasn’t able to sink the time into the Cut that I wanted to. In fact, I’m just NOW starting to get caught up writing about all the stuff that happened last summer – concerts, vacations, album reviews, etc. And I still have more to do! So next issue, our “end of year recap” issue, will also feature some reviews from last summer, and other takes and B-S I need to get out of my system.