The Mechanical Career of Councillor Orffyreus, Confidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Harrison (1693-1776) and the Heroics of Longitude

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/02/09 Ulrike Zimmermann 119 John Harrison (1693-1776) and the Heroics of Longitude 1. A Symposium and a Rediscovery bestseller, and Dava Sobel embarked on a car eer as a wellknown and respected author of 2 When American journalist Dava Sobel attended popular science books. the Longitude Symposium of Harvard Univer Dava Sobel’s first subject already was his sity at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in November tory, albeit part of an unaccountably hidden or 1993, she did not expect anything decisive to at least underrated history. John Harrison was a come out of either the conference or her attend carpenter and selftaught clockmaker, who was ance. “500 people from seventeen countries” born in Yorkshire and spent his early life in Bar came together to hold “a conference about the rowuponHumber, North Lincolnshire. He would history of finding longitude at sea,” W. H. An prob ably have spent his life in obscur ity had he drewes, curator of the scientific instruments col not solved one of the major techno logical prob lec tion at Harvard, notes in his introduction to lems of his time, the problem of how to determine the conference proceedings (Andrewes, Intro a ship’s eastwest position, its longitude, at sea. duction 1). Despite the sizable number of par Harrison has a firm place in the his tory of navi ticipants, the Longitude Symposium was at first gation, and would have been known amongs t sight a convention of specialists sharing their horologists, clock and watch makers, and nava l knowledge and discussing finer points of their historians. -

Captain Cook's Apprentice Chapter Notes

Captain Cook’s Apprentice Chapter Notes 1 Captain Cook’s Apprentice Chapter Notes For eyewitness descriptions of incidents, see Cook, Banks and Parkinson Journals, and also Hawkesworth under ‘Voyaging Accounts’ at http://southseas.nla.gov.au. The prefix Adm and reference number indicates an Admiralty series document held at the UK National Archives. Chapter 1 Black hand. The Manley family crest dates to mediaeval times. John Manley’s shield can still be seen in Middle Temple Hall. London Bridge. The first stone bridge over the Thames was opened in 1209 and stood for over 600 years. The second London Bridge opened in 1831, and the most recent in 1973. Baldwin’s Guide of 1768 gives the watermen’s rate from London to Deptford as two shillings and sixpence (half a crown). Shooting the Bridge. The dangers were very real (Jackson pp 70-1). Manley family. Isaac was descended through the younger branch of a landed family from Erbistock, in Wales. His great-great grandfather, John, fought for Cromwell and was an MP. His great-grandfather, Isaac, was Postmaster-General in Ireland, and grandfather, John (died 1743), was a Commissioner for Customs and lived at Hatton Garden. His father, also John (c1716-1801), was called to the Bar in 1739 and became a Bencher [senior member] of the Middle Temple in 1768. In 1750 he married Ann Hammond and they had five children. Isaac George Manley. Baptised St Giles-in-the-Fields, London, 3 March 1755. Given high infant mortality rates, most children were baptised quickly and Isaac would have been born about this date. -

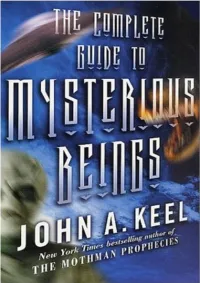

The Complete Guide to Mysterious Beings

This book is dedicated to the memory of Otto Binder, Charles Bowen, Alex Jackinson, Coral and Jim Lorenzen, Ivan T. Sanderson and all the others who spent their lives pursuing the unknown and the unknowable. CONTENTS 1. A World Filled with Ambling Nightmares 2. ”The Uglies and the Nasties” 3. Demon Dogs and Phantom Cats 4. Flying Felines 5. The Incomprehensibles 6. Giants in the Earth or ”Marvelous Big Men and Great Enmity” 7. The Hairy Ones 8. Meanwhile in Russia 9. Big Feet and Little Brains 10. Creatures from the Black Lagoon 11. Those Silly ”Flying Saucer” People 12. The Big Joke from Outer Space 13. Cattle Rustlers from the Skies 14. The Grinning Man 15. Cherubs, Angels, and Greys 16. The Bedroom Invaders 17. Winged Weirdos 18. The Man-Birds 19. West Virginia's ”Mothman” 20. Unidentified Swimming Objects 21. Scoliophis Atlanticus 22. The Great Sea Serpent of Silver Lake, New York 23. The Yellow Submarine Caper 24. Something Else... Afterword: 2002 ONE A WORLD FILLED WITH AMBLING NIGHTMARES No matter where you live on this planet, someone within two hundred miles of your home has had a direct confrontation with a frightening apparition or inexplicable ”monster” within the last generation. Perhaps it was even your cousin or your next-door neighbor. There is a chance – a very good one – that sometime in the next few years you will actually come face to face with a giant hair-covered humanoid or a little man with bulging eyes, surrounded by a ghostly greenish glow. An almost infinite variety of known and unknown creatures thrive on this mudball and appear regularly year after year, century after century. -

The Story of Rupert T Gould – the Flawed Genius Who Rediscovered the Harrison Sea Clocks

Restoration The story of Rupert T Gould – the flawed genius who rediscovered the Harrison sea clocks Timothy Treffry Time Restored Until the publication of Dava Sobel’s phenomenal bestseller Longitude, in 1995, By Jonathan Betts the name and achievements of John Harrison were known only to a small band Oxford University Press and the of horological devotees. Longitude struck a chord though, and was followed by National Maritime Museum, 2006 two films for television and later a stage play. In the major film made by Charles Hardback, 14.5 cm x 22 cm Sturridge for Granada in 1999, Michael Gambon produced a remarkable 480 pages performance as John Harrison, but his story was also interwoven with that of Price: £35 Jeremy Irons' character, Lt Commander RT Gould – a complex figure credited with ISBN 0-19-856802-9 the rediscovery and restoration of Harrison’s sea clocks. The story of polymath and horologist Rupert Thomas Gould (1890–1948) has now been retold in a painstakingly researched and beautifully written biography by Jonathan Betts, Curator of the Harrison timekeepers at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. Time Restored is subtitled The Harrison timekeepers and RT Gould, the man who knew (almost) everything, and there is a lot of meat, even in the title. At one level, ‘Time Restored’ refers simply to Gould’s work on the timekeepers, but the book also presents a great deal of social history and we are given a (not always edifying) picture of upper middle-class, late Victorian, Edwardian, and mid 20th century life. The subtitle refers to Gould’s performances on the classic BBC radio programmes: Children’s Hour and Brains Trust. -

The Marine Chronometer: It's History & Development

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship Faculty Publications 2013 [Review] The Marine Chronometer: It's History & Development David Rachlin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/facpub Recommended Citation Rachlin, David. 2014. "The Marine Chronometer: Its History and Development." Reference Reviews 28 (1): 33-34. doi:10.1108/RR-09-2013-0249. https://doi.org/10.1108/RR-09-2013-0249. This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marine Chronometer: Its history and development By Rupert T Gould Edited by Susanna Hecht Forward by Jonathan Betts Antique Collectors’ Club Old Martlesham, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK 1 Volume ISBN 978 1 85149 365 4 (Hardbound) Keywords: Longitude, Marine Chronometer, Rupert Gould, John Harrison, Marine Navigation rd In the 3 century BCE, the first system of latitude and longitude was devised. About 100 years later, Hipparchus proposed a system of comparing local time with a fixed standard time. The modern concepts of longitude and time however were not developed until Al-Biruni in the th 11 century. The use of a chronometer was first suggested by Dutch scientist Gemma Frisius in 1530. That began over 200 years of mankind’s quest to develop an accurate marine timekeeper that could withstand the changes in temperature, humidity, magnetic field and pitching of a ship on a long ocean voyage in the age of sail. -

Appendix 1: a Select Timeline

Appendix 1: A Select Timeline 1292 Richard of Wallingford, English astronomer/horologist born 1336 Richard of Wallingford, English astronomer/horologist died 1386 Salisbury cathedral clock built 1410 Prague clock installed 1473 Nicolaus Copernicus born 1524 Roger Boyle born in Herefordshire but lived in Kent, England 1525 John Stowe, surveyor of London, born 1532 Nicholas Oursian, French clockmaker first recorded 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus died 1546 Tycho Brahe born 1564 Galileo Galilei born 1566 Richard Boyle was born in Canterbury 1576 Roger Boyle died in Preston, Faversham 1590 Nicholas Oursian died 1600 Lantern clocks became common 1601 Tycho Brahe died 1602 Galileo Galilei discovered pendulum swing independent of amplitude. 1605 John Stowe, surveyor of London, died 1610 Galileo Galilei describes moons associated with Jupiter 1629 Christaan Huygens born 1633 Samuel Pepys born 1635 Robert Hooke born 1639 Thomas Tompion born 1642 Sir Isaac Newton born 1642 Galileo Galilei died 1643 Richard Boyle died 1644 Ole Christensen Rømer born 1646 John Flamsteed born 1650 Sir Cloudesley Shovell born 1650 Duke of Marlborough (John Churchill) born 1656 Professor Edmund Halley born 1657 Christaan Huygens patented pendulum clock 1657 Robert Hooke invented the anchor escapement 1660–1669 Samuel Pepys created his private diaries 1662 Dr Richard Bentley, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, born 1663 Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy-Carignan-Soissons born 1666 Great Fire of London 1667 Jonathan Swift born 1668 John Rowley born 1672 Sir Richard Steele born -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Chronometers and Chronometry on British Voyages of Exploration, 1819-1836 Emily Jane Akkermans Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh School of GeoSciences 2020 Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed by myself and that no part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree of qualification. The work described is my own unless otherwise stated. Emily Jane Akkermans November 2020 i Dedication In memory of my father, Frans Akkermans ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I am extremely grateful to my supervisors, Charlie Withers, Richard Dunn and Megan Barford for their invaluable advice, continuous support and patience during my doctoral studies. I could not have wished for better supervision during the writing of my thesis. -

Arthur C. Clarke's Chronicles of the Strange and Mysterious

Arthur C. Clarke's Chronicles Of The Strange And Mysterious Contents: Book Cover (Front) (Back) Scan / Edit Notes Picture Plates (Paberback) First Set Of Plates Second Set Of Plates Foreword by Arthur C. Clarke 1 - The Beasts that Hide from Man 2 - The Silence of the Past 3 - Out of the Blue 4 - Strange Tales from the Lakes 5 - Of Monsters and Mermaids 6 - Supernatural Scenes 7 - Fairies, Phantoms, Fantastic Photographs 8 - Mysteries from East and West 9 - Where Are They? Acknowledgements Photo Credits (Removed) Index (Removed) Scan / Edit Notes This is the paper-back version which has less pictures than the hard-back version. I have scanned both but due to the large size increase only the paper-back version will be posted. Versions available and duly posted: Format: v1.0 (Text) Format: v1.0 (PDB - open format) Format: v1.5 (HTML) Format: v1.5 (PDF - no security) Format: v1.5 (PRC - for MobiPocket Reader - pictures included) Genera: Supernatural Extra's: Pictures Included (for all versions) Copyright: 1987 / 1989 First Scanned: 2002 Posted to: alt.binaries.e-book Note: 1. The Html, Text and Pdb versions are bundled together in one zip file. 2. The Pdf and Prc files are sent as single zips (and naturally don't have the file structure below) ~~~~ Structure: (Folder and Sub Folders) {Main Folder} - HTML Files | |- {Nav} - Navigation Files | |- {PDB} | |- {Pic} - Graphic files | |- {Text} - Text File -Salmun Plates for the Paper-Back Version First Set Of Plates A drawing of mokele-mbembe by artist David Miller based on a description given by Congolese eye- witnesses. -

The Mechanical Career of Councillor Orffyreus, Confidence

The mechanical career of Councillor Orffyreus, confidence man Alejandro Jenkins∗ High Energy Physics, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-4350, USA and Escuela de F´ısica, Universidad de Costa Rica, 11501-2060 San Jos´e,Costa Rica (Dated: Jan. 2013, last revised Mar. 2013; to appear in Am. J. Phys. 81) In the early 18th century, J. E. E. Bessler, known as Orffyreus, constructed several wheels that he claimed could keep turning forever, powered only by gravity. He never revealed the details of his invention, but he conducted demonstrations (with the machine's inner workings covered) that persuaded competent observers that he might have discovered the secret of perpetual motion. Among Bessler's defenders were Gottfried Leibniz, Johann Bernoulli, Professor Willem 's Gravesande of Leiden University (who wrote to Isaac Newton on the subject), and Prince Karl, ruler of the German state of Hesse-Kassel. We review Bessler's work, placing it within the context of the intellectual debates of the time about mechanical conservation laws and the (im)possibility of perpetual motion. We also mention Bessler's long career as a confidence man, the details of which were discussed in popular 19th-century German publications, but have remained unfamiliar to authors in other languages. Keywords: perpetual motion, early modern science, vis viva controversy, scientific fraud PACS: 01.65.+g, 45.20.dg I. INTRODUCTION The perpetual motion devices whose drawings add mystery to the pages of the more effusive encyclopedias do not work either. Nor do the metaphysical and theological theories that customarily declare who we are and what manner of thing the world is. -

Chronometers, Charts, Charisma: on Histories of Longitude

Science Museum Group Journal Chronometers, charts, charisma: on histories of longitude Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Simon Schaffer 10-09-2014 Cite as 10.15180; 140203 Discussion Chronometers, charts, charisma: on histories of longitude Published in Autumn 2014, Issue 02 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/140203 Chronometers, charts, charisma: on histories of longitude Charismatic megafauna are exotically impressive creatures guaranteed to attract immediate public fascination and sympathy. Their images and life stories provide indispensable resources for keen environmental campaign groups and publicists. The expression itself – charismatic megafauna – is barely a few decades old. Part of its point is to recall and contrast the hosts of apparently less alluring beings at least as crucial and fragile, possessed of their own cultures and needs, but who instead somehow have to rely for survival and support on the easier appeal of these larger and more compelling beasts. It is tempting to apply the term to less animate, but no less strangely charismatic, articles. In a host of salvage operations and museum collections, objects such as dinosaurs, Pharaonic mummies, totem poles and railway engines all play such roles. The charismatic megafauna of the National Maritime Museum include John Harrison’s astonishing 18th-century sea clocks, now widely reckoned the most important timekeepers ever constructed, not least because of their role in the determination of maritime longitude. Like so many of the artefacts currently held as part of the nation’s heritage, their highly troubled careers embody a remarkable range of themes in craftsmanship and science, conservation and administration, repute and controversy. -

THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Bermuda Triangle / Astronomers and Ufos

THE ZETETIC THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Bermuda Triangle / Astronomers and UFOs / Einstein and ESP / Astrology, Psychics, and Secrets / The UFO That Wasn't Published by the committee for the Scientific investigation of Claims of the Paranormal VOL. II NO. 1 FALL/WINTER 1977 B THE ZETETIC— Journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Volume II, No. 1 ISSN 0148-1096 Fall/Winter 1977 5 NEWS AND COMMENT 16 PSYCHIC VIBRATIONS ARTICLES 22 Von Daniken's Golden Gods, by Ronald D. Story 36 Critical Reading, Careful Writing, and the Bermuda Triangle, by Larry Kusche 41 Pseudoscience at Science Digest, by James E. Oberg and Robert Sheqffer 45 Do Fairies Exist? by Robert Sheaffer 53 Einstein and ESP, by Martin Gardner 57 N-Rays and UFOs: Are They Related? by Philip J. Klass 62 What They Aren't Telling You: Suppressed Secrets of the Psychic World, Astrological Universe, and Jeane Dixon, by Dennis Rawlins BOOK REVIEWS 84 P. A. Sturrock, Report on a Survey of the Membership of the American Astronomical Association Concerning the UFO Problem (Reviews by Philip J. Klass and John P. Robinson, responses by P. A. Sturrock) 93 Charles Berlitz, Without a Trace (Reviews by Larry Kusche and Philip J. Klass) 102 Roy Wallis, The Road to Total Freedom: A Sociological Analysis of Scientology (Richard de Mille) 104 Tom Valentine, Psychic Surgery; William A. Nolen, Healing: A Doctor in Search of a Miracle; C. Norman Shealy, Occult Medicine Can Save Your Life; John A. Richardson and Patricia Griffin, Lae trile Case Histories (Laurent A. -

Making Time.Pages

When I read ‘Longitude’, Dava Sobel’s science factual account of the discovery Longitude at sea, I was certain that it could not be made into a film. True, nobody, had asked me to make a film, but if you make films, everything you read becomes a possible project , or in this case an impossible one. The story of 18th Century carpenter John Harrison, who solved the problem of working out where you are at sea, takes place over forty years, although the hero fights a battle against seemingly insuperable odds, he does not win until he is eighty years old and the main tension resides in whether a clock is going one second faster or slower, not exactly Ben Hur. Thus it was with mixed feelings that I attended a meeting at Channel 4 almost exactly a year ago on September 16th to discuss the possibility of such a film. The rights to the book had been bought some time before by Granada Television and Channel 4 saw it as a potential millennial project but had no fixed ideas upon how this should achieved, and as I walked into the room neither had I. I did however have a clue. I had swiftly leafed through the book to check on something that had stuck in the back of my mind. Rupert Gould, a naval officer, not from the 18th Century, but the early part of this century, who invalided out of the service at the start of the first world war after a nervous breakdown, had discovered the abandoned Harrison clocks in a cellar at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.