Historical Study of the Arabaic Teaching in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophy of Mystic Poet Hason Raja and a Folk Music Academy

Hason Raja, the mystic poet & his philosophy An imaginary folk music academy at his birth place S U N A M G O N J , B A N G L A D E S H “What kind of hut I will build, While everything on barrenness.” Hason Raja (1854-1922) Hason Raja Folk Music Academy An imagery project based on the mystic poets’ philosophy in his birthplace Mallikpur Sunamgonj Name of author Ar. Sayed Ahmed 2005335019 June, 2012 Department of Architecture School of applied sciences Shahjalal University of Science & Technology Sylhet-3114, Bangladesh ABSTRACT Music is the most powerful formation of all arts. It is the ultimate destination for all other section of art, because all the arts meet to an end on music. Again the proletariat literature, the sub-alter literature and folklore music might have the most intimate relationship between the nature & human mind. The reason has its origin to reflection over human mind by the impact of nature. Water’s wave splashes to the shores creates some sound, breeze passing the branches of trees also left some sound, the rhyme of fountain, songs of birds, mysterious moonlit night, and so on. Actually music is the first artistic realization of human mind. Thus development of interaction through language is mostly indebted to music and the first music of human kind should be a folk one. That’s why the appeal of folk music is universal. From this context, my design consideration, the institute proposed for Hason Raja Sangeet (music) Academy is based on the rural-organic spatial order, use of indigenous building materials and musical education adapting the vastness of Haor (marshy) basin nature. -

List of Govt. Colleges

LIST OF GOVT. COLLEGES '-' !•_•• '!- \ i Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statiscs (BANBEIS) Ministry of Education 1, Sonargaon Road Dhaka -1205 JANUARY-1999 LIST OF GOVERNMENT COLLEGE-19 98-9 9 27/01/99 Division : BARI SAL >-EXIAL! INSTITUTION INSTITUTE NAME THANA DISTRICT ••JO.:-'- |CODE ;1 104 2-8 5 201 BURGUNA GOVT. COLLEGE SADAR BURGUNA 2 10 6075204 GOVT.BAKERGANJ COLLEGE BAKERGANJ BARISAL 3 .106105201 GOVT. F. H.. COLLEGE CHAKHAR BANARIPARA BARISAL 4 106325201 GOVT. GOURNADI COLLEGE GOURNADI BARISAL • 5 106995202 GOVT. SYED HATIM ALI COLLEGE KOTWALI BARISAL 6 "10699520.3 BARI SAL GOVT.MOHILA COLLEGE SADAR BARISAL 7 .10 6995401 GOVT. B. M. COLLEGE SADAR BARISAL . S 106995404 GOVT. BARISAL'COLLEGE SADAR BARISAL • + $ •109185 20.J. BHOLA GOVT. COLLEGE SADAR BHOLA 10 109185.262 GOVT.FAZILATUNNESSA MOHILA COL SADAR BHOLA GOVT.SHAHBAJPUR COLLEGE LALMOHAN BHOLA .JHALAKATI GOVT. COLLEGE SADAR JHALAKATI 4 3 '• ; -.-.I 78 95 5201. PATUAKHALI GOVT.MOHILA COLLEGE SADAR PATUAKHALI 1 4 ..• 17895 5401 PATUAKHALI GOVT. COLLEGE SADAR PATUAKHALI "179145 201 BHANDARIA GOVT. COLLEGE. BHANDARIA PIROJPUR 179585201 MATHBARIA GOVT. COLLEGE MATHBARIA PIROJPUR 179765201 GOVT. SWARUPKATI COLLEGE NESARABAD PIROJPUR IS -179805201 P'IROJPUR GOVT. WOMEN'S COLLEG SADAR PIROJPUR 19 .179805301 GOVT. SOHRAWARDY COLLEGE SADAR PIROJPUR 'BANBEIS LIST OF GOVERNMENT COLLEGE-1998-99 27/01/99 Division : CHITTAGONG ...SERIAL! INSTITUTION! INSTITUTE NAME THANA ! DISTRICT h i !CODE ! i ' 1 20 3145 201 BANDARBAN GOVT. COLLEGE SADAR BANDARBAN •2 212135202 BRAHMANBARIA GOVT.MOHILA COLL SADAR BRAHMANBARIA '3. .212135301 BRAHMANBARIA GOVT. COLLEGE SADAR BRAHMANBARIA 4 .•,.•-•••212855201 NABINAGA'R GOVT. COLLEGE NABINAGAR BRAHMANBARIA 5 2132 25201 CHANDPUR GOVT. MAHILA COLLEGE SADAR CHANDPUR 6 213225401 CHANDPUR GOVT. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Ssc 2014.Pdf

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION SYLHET SECONDARY SCHOOL CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION - 2014 SCHOLARSHIP (According to Roll No) TALENT POOL SCHOLARSHIP FOR SCIENCE GROUP TOTAL NO. OF SCHOLARSHIP - 50 ( Male - 25, Female - 25 ) SL_NO CENTRE ROLL NAME SCHOOL 1 100-S. C. C. 100020 AKIBUL HASAN MAZUMDER SYLHET CADET COLLEGE, SYLHET 2 100-S. C. C. 100025 ABDULLAH MD. ZOBAYER SYLHET CADET COLLEGE, SYLHET 3 100-S. C. C. 100039 ADIL SHAHRIA SYLHET CADET COLLEGE, SYLHET 4 100-S. C. C. 100044 ARIFIN MAHIRE SYLHET CADET COLLEGE, SYLHET 5 100-S. C. C. 100055 MD. RAKIB HASAN RONI SYLHET CADET COLLEGE, SYLHET 6 100-S. C. C. 100061 TANZIL AHMED SYLHET CADET COLLEGE, SYLHET MUSHFIQUR RAHMAN 7 101-SYLHET - 1 100090 SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET CHOWDHURY 8 101-SYLHET - 1 100091 AMIT DEB ROY SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 9 101-SYLHET - 1 100145 MD. SHAHRIAR EMON SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 10 101-SYLHET - 1 100146 SHEIKH SADI MOHAMMAD SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 11 101-SYLHET - 1 100147 PROSENJIT KUMAR DAS SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 12 101-SYLHET - 1 100149 ANTIK ACHARJEE SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 13 101-SYLHET - 1 100193 SIHAN TAWSIK SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 14 101-SYLHET - 1 100197 SANWAR AHMED OVY SYLHET GOVT. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 15 102-SYLHET - 2 100714 SNIGDHA DHAR BLUE BIRD HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 16 102-SYLHET - 2 100719 NAYMA AKTER PROMA BLUE BIRD HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 17 102-SYLHET - 2 100750 MADEHA SATTAR KHAN BLUE BIRD HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 18 102-SYLHET - 2 100832 ABHIJEET ACHARJEE JEET BLUE BIRD HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET Page 3 of 51 SL_NO CENTRE ROLL NAME SCHOOL 19 102-SYLHET - 2 100833 BIBHAS SAHA DIPTO BLUE BIRD HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 20 102-SYLHET - 2 100915 DIPAYON KUMAR SIKDER BLUE BIRD HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 21 102-SYLHET - 2 100916 MUBTASIM MAHABUB OYON BLUE BIRD HIGH SCHOOL, SYLHET 22 102-SYLHET - 2 100917 MD. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ISO 9001: 2015 CERTIFIED ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ISO 9001: 2015 CERTIFIED VISION Economic upliftment of the country by reaching electricity to all through reliable transmission. MISSION Efficient and effective management of national power grid for reliable and quality transmission as well as economic dispatch of electricity throughout the country. gywRee‡l© RvwZi wcZv e½eÜz †kL gywReyi ingvb I Zuvi cwiev‡ii knx` m`m¨‡`i cÖwZ web¤ª kÖ×v gywRee‡l© wcwRwmweÕi M„nxZ K‡g©v‡`¨vM RvwZi wcZv e½eÜz †kL gywReyi ingv‡bi Rb¥kZevwl©Kx myôyfv‡e D`hvc‡bi j‡¶¨ wcwRwmwe wb‡¤œv³ Kg©cwiKíbv MÖnY I ev¯Íevqb Ki‡Q Kg©cwiKíbv Ges miKvwi wb‡`©kbv ev¯Íevq‡bi j‡¶¨ wcwRwmwe GKwU g~j KwgwU Ges cvuPwU DcKwgwU MVb K‡i‡Q| kZfvM we`y¨Zvqb Kvh©µg ev¯Íevqb msµvšÍ K) 2020 mv‡ji g‡a¨ ‡`ke¨vcx kZfvM we`y¨Zvq‡bi j‡¶¨ wbf©i‡hvM¨ we`y¨r mÂvjb Kiv; L) ‰e`y¨wZK miÄvgvw`i Standard Specification ‰Zixi D‡`¨vM MÖnY; M) we`y¨r mÂvj‡bi ‡¶‡Î wm‡óg jm ‡iv‡a Kvh©Kix c`‡¶c MÖnY; N) we`y¨r wefv‡Mi mswkøó KwgwU KZ©…K M„nxZ Kvh©µ‡gi mv‡_ mgš^q K‡i cª‡qvRbxq Ab¨vb¨ Kvh©µg MÖnY; DrKl©Zv Ges D™¢vebx Kg©KvÛ msµvšÍ K) gywRe el©‡K we`y¨r wefvM KZ©…K Ô‡mev el©Õ wn‡m‡e ‡Nvlbvi ‡cÖw¶‡Z ‡m Abyhvqx Kvh©µg m¤úv`b Kiv; L) ‰e`y¨wZK Lv‡Z ‡`‡k I we‡`‡k `¶ Rbkw³i Pvwn`v c~iYK‡í ‰e`y¨wZK Kg©‡ckvq `¶ Rbkw³ M‡o ‡Zvjvi Rb¨ ÔgywRe e‡l©Õ cÖwk¶Y Kg©m~wPi gva¨‡g b~¨bZg 210 Rb †eKvi hyeK‡K gvbe m¤ú‡` iƒcvšÍi Kiv; M) e½eÜy ‡kL gywReyi ingv‡bi Rb¥kZevwl©Kx D`hvc‡bi j‡¶¨ ‰ZwiK…Z ‡K›`ªxq I‡qemvB‡Ui m‡½ wcwRwmweÕi wjsK ¯’vcb; N) we`y¨r wefv‡Mi mswkøó KwgwU KZ©…K M„nxZ Kvh©µ‡gi mv‡_ mgš^q K‡i cÖ‡qvRbxq -

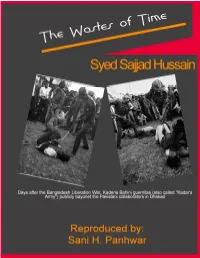

The Wastes of Time by Syed Sajjad Hussain

THE WASTES OF TIME REFLECTIONS ON THE DECLINE AND FALL OF EAST PAKISTAN Syed Sajjad Husain 1995 Reproduced By: Sani H. Panhwar 2013 Syed Sajjad Syed Sajjad Husain was born on 14th January 1920, and educated at Dhaka and Nottingham Universities. He began his teaching career in 1944 at the Islamia College, Calcutta and joined the University of Dhaka in 1948 rising to Professor in 1962. He was appointed Vice-Chancellor of Rajshahi University July in 1969 and moved to Dhaka University in July 1971 at the height of the political crisis. He spent two years in jail from 1971 to 1973 after the fall of East Pakistan. From 1975 to 1985 Dr Husain taught at Mecca Ummul-Qura University as a Professor of English, having spent three months in 1975 as a Fellow of Clare Hall, Cambridge University. Since his retirement in 1985, he had been living quietly at home and had in the course of the last ten years published five books including the present Memoirs. He breathed his last on 12th January, 1995. A more detailed account of the author’s life and career will be found inside the book. The publication of Dr Syed Sajjad Husain’s memoirs, entitled, THE WASTES OF TIME began in the first week of December 1994 under his guidance and supervision. As his life was cut short by Almighty Allah, he could read and correct the proof of only the first five Chapters with subheadings and the remaining fifteen Chapters without title together with the Appendices have been published exactly as he had sent them to the publisher. -

Administrative Setup and Academic Pursuits

Chapter · Ill Administrative Setup and Academic Pursuits I. The Principals, Academic Staff And standard of Education When the University of Calcutta began to function and turn out graduates, Rajshahi people became desirous of having higher education and began to think of starting a college. In 1873, First Arts classes were added to the Rajshahi Zilla School and it was raised to a second grade college, which was named Bauleah High School. The FA. classes were opened on the 1st April, 1873 with only six students on the 1 rolls. The Head Master of the Rajshahi Zilla School, Haragobinda Sen, was called upon to act as the Principal of the college when it was established. He was described in the despatch of Lord Hardinge, the Governor-General as "the most successful student for the year 1848." With Haragobinda Sen, Some of teachers of he school were also required to teach in the college as well. The Head Master reported that the teachers were not inclined to undertake the charge because of small emoluments offered to them. 2 The results were not very encouraging at first; all the five candidates for the University examination got plucked. In 1875 two out of seven candidates passed, named Nikunja Mohan Lahiri and Sree Narayan Munshi. They got second and third divisions respectively. It is noted that, Nikunja Mohan Lahiri securing a senior scholarship. In 1877, efforts were made for starting a first grade college, and the Rajshahi Association began to earn subscriptions. The Government of Bengal sanctioned the scheme in their letter No.2878, dated 1st October, 1877. -

Term Loan Beneficiary Wise Utilisation Report from 20.01.16 to 03.03.16

Term Loan UC report from 20.01.16 to 03.03.16 Sanction Communit Amount of NMDFC Slno Name beneficiary_cd Father's/Husband's Name Address Pin Code District Sector Gender Area Letter Print y Finance(Rs) Share(Rs) Date ABUJAR HOSSAIN A56028/MBD/58/16 SOFIKUL ISLAM VILL- NAMO CHACHANDA, PO- MURSHIDABA 1 742224 CLOTH SHOP MUSLIM MALE RURAL 80,000 72,000 12/02/2016 JOYKRISHNAPUR, PS- SAMSERGANJ D ARSAD ALI A56037/MBD/55/16 LATE MD MOSTAFA VILL- JOYRAMPUR, PO- BHABANIPUR, PS- MURSHIDABA WOODEN 2 742202 MUSLIM MALE RURAL 50,000 45,000 12/02/2016 FARAKKA D FURNITURE SHOP ABU TALEB AHAMED A56040/CBR/57/16 MAHIRUDDIN AHAMED VILL CHHATGENDUGURI PO STATIONARY 3 736159 COOCH BEHAR MUSLIM MALE RURAL 70,000 63,000 02/03/2016 KASHIRDANGA SHOP ABDUL MANNAN A56042/CBR/58/16 SABER ALI VILL- NABANI, PO- GITALDAHA , PS- SEASONAL 4 736175 COOCH BEHAR MUSLIM MALE RURAL 80,000 72,000 24/02/2016 DINAHTA CROPS TRADING MISTANNA ATAUR RAHAMAN A56101/DDP/58/16 LATE ACHIMADDIN AHAMEDVILL BARAIDANGA PO KALIMAMORA DAKSHIN 5 733132 VANDAR (SWEET MUSLIM MALE RURAL 80,000 72,000 13/02/2016 DINAJPUR SHOP) AMINUR RAHAMAN A56110/DDP/59/16 AAIDUR RAHAMAN JHANJARI PARA DAKSHIN 6 733125 GARMENTS SHOP MUSLIM MALE RURAL 90,000 81,000 13/02/2016 DINAJPUR ANARUL HAQUE A56131/NDA/60/16 NURUL ISLAM SK VILL. CHAPRA BUS STAND PO. BANGALJHI 7 741123 NADIA MEDICINE SHOP MUSLIM MALE RURAL 100,000 90,000 15/02/2016 AKIMUDDIN A56206/PRL/52A/16 KHALIL CHOWDHURY VILL+PO- KARKARA, PS- JOYPUR 8 723213 PURULIA GENERAL STORE MUSLIM MALE RURAL 25,000 22,500 13/02/2016 CHOWDHURY ARIF KAZI A56209/PRL/52A/16 LALU KAZI VILL- KANTADI, PO+PS- JHALDA 9 723202 PURULIA FURNITURE SHOP MUSLIM MALE URBAN 25,000 22,500 13/02/2016 ANUAR ALI A56282/UDP/58/16 GUFARUDDIN PRADHAN VILL- BHADRATHA, PO- BHUPAL PUR, PS- UTTAR HARDWARE 10 733143 MUSLIM MALE RURAL 80,000 72,000 24/02/2016 ITAHAR DINAJPUR SHOP ANASARUL SEKH A56432/BBM/53/16 EMDADUL ISLAM VILL BAHADURPU 11 731219 BIRBHUM GROCERY SHOP MUSLIM MALE RURAL 30,000 27,000 17/02/2016 ANISH GOLDAR A56467/HWH/55/16 LATE. -

Negotiating Modernity and Identity in Bangladesh

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 9-2020 Thoughts of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity and Identity in Bangladesh Humayun Kabir The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4041 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THOUGHTS OF BECOMING: NEGOTIATING MODERNITY AND IDENTITY IN BANGLADESH by HUMAYUN KABIR A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUMAYUN KABIR All Rights Reserved ii Thoughts Of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity And Identity In Bangladesh By Humayun Kabir This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________ ______________________________ Date Uday Mehta Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ ______________________________ Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Uday Mehta Susan Buck-Morss Manu Bhagavan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Thoughts Of Becoming: Negotiating Modernity And Identity In Bangladesh By Humayun Kabir Advisor: Uday Mehta This dissertation constructs a history and conducts an analysis of Bangladeshi political thought with the aim to better understand the thought-world and political subjectivities in Bangladesh. The dissertation argues that political thought in Bangladesh has been profoundly structured by colonial and other encounters with modernity and by concerns about constructing a national identity. -

Progress of Higher Education in Colonial Bengal and After -A Case Study of Rajshahi Colle.Ge

PROGRESS OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN COLONIAL BENGAL AND AFTER -A CASE STUDY OF RAJSHAHI COLLE.GE. (1873-1973) Thesis Submitted to the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. ( ( l r"<t •· (•(.j 1:'\ !. By Md. Monzur Kadir Assistant Professor of Islamic History Rajshahi College, Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Under the Supervision of Dr. I. Sarkar Reader in History University of North Bengal,· Darjeeling, West Bengal, India. November, 2004. Ref. '?:J 1B. s-4 C124 oqa4 {(up I 3 DEC 2005 Md. Monzur Kadir, Assistant Professor, Research 5 cholar, Islamic History, Department of History Rajshahi College, Uni~ersity of North Bengal Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Darjeeling, India. DECLARATION . I hereby declare that the Thesis entitled "PROGRESS OF HIGHER EDUc;ATION IN COLONIAL BENGAL AND AFTER- A CASE STUDY OF RAJSHAHI COLLEGE (1873-1973)," submitted by me for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of the University of North Bengal, is a record of research work done by me and that the Thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any other Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship and similar other titles. II · 8 "' (Jl~Mt ~~;_ 10. -{ (Md. Monzur Kadir) Acknowledgement------------ This dissertation is the outcome of a doctoral research undertaken at the University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, India. It gives me immense pleasure to place on record the great help and co-operation. I received from several persons and institutions during the preparation of this dissertation. I am already obliged to Dr. I. Sarkar, Reader in History. North Bengal University who acted as my supervisor and for his urqualified support in its planning and execution. -

The Gauhati High Court

Gauhati High Court List of candidates who are provisionally allowed to appear in the preliminary examination dated 6-10-2013(Sunday) for direct recruitment to Grade-III of Assam Judicial Service SL. Roll Candidate's name Father's name Gender category(SC/ Correspondence address No. No. ST(P)/ ST(H)/NA) 1 1001 A K MEHBUB KUTUB UDDIN Male NA VILL BERENGA PART I AHMED LASKAR LASKAR PO BERENGA PS SILCHAR DIST CACHAR PIN 788005 2 1002 A M MUKHTAR AZIRUDDIN Male NA Convoy Road AHMED CHOUDHURY Near Radio Station CHOUDHURY P O Boiragimoth P S Dist Dibrugarh Assam 3 1003 A THABA CHANU A JOYBIDYA Female NA ZOO NARENGI ROAD SINGHA BYE LANE NO 5 HOUSE NO 36 PO ZOO ROAD PS GEETANAGAR PIN 781024 4 1004 AASHIKA JAIN NIRANJAN JAIN Female NA CO A K ENTERPRISE VILL AND PO BIJOYNAGAR PS PALASBARI DIST KAMRUP ASSAM 781122 5 1005 ABANINDA Dilip Gogoi Male NA Tiniali bongali gaon Namrup GOGOI P O Parbatpur Dist Dibrugarh Pin 786623 Assam 6 1006 ABDUL AMIL ABDUS SAMAD Male NA NAYAPARA WARD NO IV ABHAYAPURI TARAFDAR TARAFDAR PO ABHAYAPURI PS ABHAYAPURI DIST BONGAIGAON PIN 783384 ASSAM 7 1007 ABDUL BASITH LATE ABDUL Male NA Village and Post Office BARBHUIYA SALAM BARBHUIYA UTTAR KRISHNAPUR PART II SONAI ROAD MLA LANE SILCHAR 788006 CACHAR ASSAM 8 1008 ABDUL FARUK DEWAN ABBASH Male NA VILL RAJABAZAR ALI PO KALITAKUCHI PS HAJO DIST KAMRUP STATE ASSAM PIN 781102 9 1009 ABDUL HANNAN ABDUL MAZID Male NA VILL BANBAHAR KHAN KHAN P O KAYAKUCHI DIST BARPETA P S BARPETA STATE ASSAM PIN 781352 10 1010 ABDUL KARIM SAMSUL HOQUE Male NA CO FARMAN ALI GARIGAON VIDYANAGAR PS -

District Election Plan

GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER CACHAR :: SILCHAR DISTRICT ELECTION PLAN PANCHAYAT ELECTION 2017-18 Page 1 INDEX Sl No Topic Page 1 Map of Cachar District 1 2 Introduction 1-3 3 Reservation of Z. P. Member Constituencies 4 4 Reservation of A. P. Presidents & Vice Presidents 5 Reservation of A.P. Members, G. P. Presidents & G. P. Vice 5 6-10 Presidents 6 Different Election Cell & their respective Action Plan 11-44 7 Detail of Zone & Sector-wise Polling Stations 45-136 8 Counting Plan 137 9 Important Contacts Annexure-I Page 2 DISTRICT PROFILE Cachar district is located in the southernmost part of Assam. It is bounded on the north by Barail and Jayantia hill ranges, on the south by the State of Mizoram and on the west by the districts of Hailakandi and Karimganj. The district lies between 92° 24' E and 93° 15' E longitude and 24° 22' N and 25° 8' N latitude. The total geographical area of the district is 3,786 Sq. Km. The Barak is the main river of the district and apart from that there are numerous small rivers which flow from Dima Hasao district, Manipur or Mizoram. The district is mostly made up of plains, but there are a number of hills spread across the district. Cachar receives an average annual rainfall of more than 3,000mm. The climate is Tropical wet with hot and wet summers and cool winters. The climatic condition of this district is significant for humidity in summer season and it is often intolerable.