1 To: Representative Jim Moran (D-VA) Subject: Felon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Bulletin

WANADA Bulletin # 39-03 September 29, 2003 REGULATORY UPDATE: “Do-Not-Call” Registry in Legal Limbo But WANADA Issues Guidelines for Oct. 1 Telemarketing Rules s we went to press, the create the “do-not-call” list. The They got little sympathy in A Federal Trade ruling involved a lawsuit Congress, however. In a rare Commission’s national “do-not- brought by telemarketers who display of speed and call” list against telemarketers estimated the “do-not-call” list bipartisanship last Thursday, the was facing its second 11th-hour – which has already registered House voted 412-8 and the legal challenge, and it was more than 50 million people – Senate 95-0 to pass a bill making unclear if Congress could act and could cut its business in half clear that the FTC has the cause the Oct. 1, 2003 effective and cost the telemarketing authority to enforce the “do-not- date for the “do-not-call” registry industry $50 billion in sales call” list. to kick in on time. each year. (Continued on page 3) However, since the legal DEALERS IN THE SPOTLIGHT challenge only affects the “do- not-call” registry, WANADA Congressman Meets With Don Beyer as Part of senior staff and legal counsel, AIADA’s Driving Change Grassroots Campaign Hamilton and Hamilton, working with NADA lawyers, prepared a memorandum summarizing all the new telemarketing requirements, many of which do become effective this week. The memorandum was mailed to all dealer members last week. The first legal challenge came on Sept. 24, when U.S. District Judge Lee R. -

News Release Representative Jim Moran United States Congress Eighth District of Virginia

Congressman Jim Moran's Website Page 1 of 3 Medicare Information Page Small Business Page Weekly Column Issues Biography | Press Room | | | | | News Release Representative Jim Moran United States Congress Eighth District of Virginia For Immediate Release: Monday, July 7, 2003 Contact: Dan Drummond 202-225-4376 Arlington and Alexandria Partner to Improve Four Mile Run Watershed Using Federal Funds Moran Secured WASHINGTON, July 7th - An historic project teaming Arlington County with the city of Alexandria to clean and improve the Four Mile Run watershed is using federal funds that Congressman Jim Moran, Virginia Democrat, was able to secure. "This project will improve an environmentally-sensitive area that is home to a wide array of plant and animal life in addition to the joggers and bikers who use Four Mile Run park," Moran said. The 20-acre Four Mile Run watershed spreads across Fairfax County, the city of Falls Church, Arlington County, and the city of Alexandria. In 2000, citizens from Arlington and Alexandria began looking at ways to improve flood control, clean up the watershed in their area and enhance and beautify the appearance of the park. Moran was able to secure one million dollars in funding in fiscal year 2001, available through the Environmental Protection Agency, for "the http://moran.house.gov/issues2.cfm?id=6374 2/18/2004 Congressman Jim Moran's Website Page 2 of 3 demonstration of environmental improvements to the Four Mile Run." Both localities applied for and were accepted to receive the EPA grant funds. A citizen task force was then created to work with the city and county to study, design, and complete a project that will greatly improve the Four Mile Run for generations to come. -

Sean A. Pittman, Esq

SEAN A. PITTMAN, ESQ. VISIONARY Through dynamic, astute leadership and strategic vision, I work to INCLUSIVE expand opportunities to increase intellectual contributions, lead state and national efforts, and empower individual and collective achievement RESOURCEFUL through innovative strategies and impactful solutions that propel PROVEN LEADERSHIP enterprises, people, projects, and goals to unlimited success. (772) 215-1500 LEADERSHIP & EXPERIENCE [email protected] MANAGING PARTNER AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER PITTMAN LAW GROUP, P.L., 2001–Present pittman-law.com Founder of a preeminent law and governmental affairs firm operating in Tallahassee, Miami, and Riviera Beach, Florida INTERNAL EDUCATION • Provide executive leadership as CEO, directing business development Juris Doctor strategies, overseeing business administration, and guiding financial Florida State University management and planning in alignment with the firm’s mission and vision College of Law, 1994 • Achieved exponential growth through the development and implementation Bachelor of Science, of short-term and long-term strategic plans, establishing ambitious goals for Social Sciences growth of the firm’s capacity, capabilities, revenue, and profitability Florida State University, 1990 • Instituted a business model that supports and invests in diverse ideas, intelligent contributions, collaborative, inclusive leadership, and professional growth RECOGNITIONS • Execute financial management and sustainability strategies to achieve financial goals and budgets and identify opportunities -

College of the Holy Cross Archives & Special Collections P.O

College of the Holy Cross Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 3A, Worcester, MA 01610-2395 College of the Holy Cross Archives and Special Collections Collection Inventory Accession Number: 2014- Collection Name (Title): Moran, James P., Congressional Papers Dates of Material: Size of Collection: Arrangement: Restrictions: Related Material: Preferred Citation: James P. Moran, Congressional Papers Processed on: Dec. 2014 - June 2016 Biography/History: James P. Moran was born in Buffalo, New York on May 16, 1945. He grew up in Natick, MA and attended the College of the Holy Cross on a football scholarship, graduating in 1967 with a BA in Economics. He went on to attend the University of Pittsburgh, where he received a Master’s of Public Administration in 1970. In 1979 Moran was elected to the city council of Alexandria, Virginia, which marked the beginning of a long career in politics. In 1985 and 1988 he was elected to serve as Mayor of Alexandria. He resigned in 1990 when he was elected to his first term in Congress. While a member of Congress, Moran served on the Committee of Appropriations and was a member of the LGBT Equality, Congressional Progressive, Animal Protection, Sudan, Sportsmen’s, International Conservation, Congressional Arts, Congressional Bike, Safe Climate, and Crohn’s and Colitis Caucuses. He was also co-founder of the New Democrat Coalition. He served as representative for Virginia’s 8th District until he retired at the end of his term in January 2015. After retiring from Congress Moran accepted positions as a Legislative Advisor at a D.C. area law firm, and accepted a faculty position in Virginia Tech’s School of Public and International Affairs. -

111Th Congress Gold Mouse Project Overview

111th Congress g old Mouse Proje C t Overview The State of Congressional web Sites Since 1998, the Congressional Management Foundation has assessed the quality of congressional web sites to determine how Members of Congress can use the internet to more effectively communicate with and serve citizens. The Gold Mouse Project seeks to improve these sites by identifying best and innovative practices that can be more widely adopted by House & Senate offices. in the 111th Congress evaluations, we found that there is a digital divide in Congress: the most common letter grades earned were “A” and “F”. © Congressional Management Foundation • www.pmpu.org 1 of 17 111th Congress g old Mouse Proje C t Overview what Did we Do? in 2009, CMF, with the assistance of our research partners at Harvard Kennedy School, Northeastern University, University of California–riverside, and the Ohio State University, conducted an extensive evaluation of all congressional web sites in the 111th Congress. 439 House Member web sites1 99 Senate Member web sites2 68 House & Senate Committee web sites (majority and minority) +14 House & Senate Leadership web sites 620 1 includes 433 representatives (there were two vacancies at the time of our evaluations), 5 delegates, and 1 resident commissioner. 2 There was one vacancy in the Senate at the time of our evaluations. © Congressional Management Foundation • www.pmpu.org 2 of 17 111th Congress g old Mouse Proje C t Overview what were Our Criteria? Member web sites were judged on 93 criteria in the following broad categories. The 61 committee criteria and 49 leadership criteria fell into most of these categories as well, but were adjusted to reflect their unique roles. -

Provider List Contents

Provider List Contents Provider Rating Only Supports eSignatures AFAS ......................................................................Yes ...................... 1 Allstate ..................................................................Yes ...................... 2 Allstate GAP ..............................................................Yes ...................... 3 Ally (APP Products) .......................................................Yes ...................... 4 Alpha Warranty Services ...................................................Yes ...................... 5 American Auto Guardian ....................................................Yes ...................... 6 American Guardian Warranty Services (AGW ..................................Yes ...................... 7 APPI ................................................................................................ 8 ArmorAll ............................................................................................ 9 ASC Warranty ....................................................................................... 10 ASI Profits ........................................................................................ 11 AssurancePlus ...................................................................................... 12 Audi Financial Services ............................................................................ 13 AUL ................................................................................................ 14 AutoXcel .......................................................................................... -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks on Signing the Leahy

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks on Signing the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act in Alexandria, Virginia September 16, 2011 Thank you so much, everybody. Please, please have a seat. I am thrilled to be here at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology. And thank you so much for the wonderful welcome. I want to thank Rebecca for the unbelievable introduction. Give Rebecca a big hand. In addition to Rebecca, on stage we've got some very important people. First of all, before we do, I want to thank your wonderful principal, Dr. Evan Glazer, who's right here. Stand up, Evan. [Applause] Yay! The people who are responsible for making some great progress on reforming our patent laws here today: Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont and Lamar Smith, Republican from Texas. And in addition, we've got Representative Bob Goodlatte, Representative Jim Moran, Representative Melvin Watt are all here; Becky Blank, who's our Acting Secretary of Commerce; David Kappos, who's the Director of U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. And we've got some extraordinary business leaders here: Louis Foreman, CEO of Eventys; Jessica Matthews, CEO of Uncharted Play; Ellen Kullman, CEO of DuPont; John Lechleiter, CEO of Eli Lilly. And we've got another outstanding student, Karishma Popli, your classmate. This is one of the best high schools in the country. And as you can see, it's filled with some pretty impressive students. I have to say, when I was a freshman in high school, none of my work was patentworthy. [Laughter] I was—we had an exhibit of some of the projects that you guys are doing, and the first high school student satellite, a wheelchair controlled by brain waves, robots. -

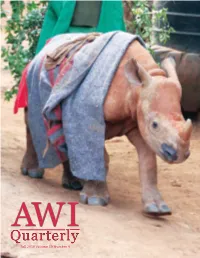

Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4

AW I Quarterly Fall 2010 Volume 59 Number 4 AWI ABOUT THE COVER Quarterly ANIMAL WELFARE INSTITUTE QUARTERLY Baby black rhinoceros, Maalim, is heading in for his evening bottle and then a good night’s sleep at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust outside Nairobi. Apparently abandoned by his FOUNDER mother, days-old Maalim (named for the ranger who rescued him) was found in the Ngulia Christine Stevens Rhino Sanctuary and taken to the Trust. Now at 20 months, he has grown quite a bit but is DIRECTORS still just hip-high! Black rhinos, critically endangered with a total wild population believed to Cynthia Wilson, Chair be around 4,200 animals, continue to be poached (along with white rhinos) for their horns. Barbara K. Buchanan “Into Africa” on p. 14 chronicles the visit to the Trust and other Kenyan conservation program John Gleiber sites by AWI’s Cathy Liss. Charles M. Jabbour Mary Lee Jensvold, Ph.D. Photo by Cathy Liss Cathy Liss 4 Michele Walter OFFICERS Cathy Liss, President Cynthia Wilson, Vice President Brutal BLM Roundups Charles M. Jabbour, CPA, Treasurer John Gleiber, Secretary THE UNNECESSARY REMOVAL OF WILD HORSES has reached an alarming rate SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE under the current administration. Thousands of horses have been and continue to Gerard Bertrand, Ph.D. be removed from their native range, and placed in short- and long-term holding Roger Fouts, Ph.D. facilities in the Roger Payne, Ph.D. Midwest. Taxpayers 10 22 Samuel Peacock, M.D. Hope Ryden pay tens of millions Robert Schmidt of dollars a year to John Walsh, M.D. -

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 105–595 "!

105TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 105±595 "! LEGISLATIVE BRANCH APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 1999 JUNE 23, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. WALSH, from the Committee on Appropriations, submitted the following REPORT together with ADDITIONAL VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 4112] The Committee on Appropriations submits the following report in explanation of the accompanying bill making appropriations for the legislative branch for the fiscal year 1999, and for other purposes. INDEX TO BILL AND REPORT Page number Bill Report Summary of bill .......................................................................................... ........ 2 Highlights of bill ......................................................................................... ........ 4 Structure of bill .......................................................................................... ........ 7 Legislative branch wide matters ............................................................... ........ 7 Art in the Capitol ....................................................................................... ........ 7 Title IÐCongressional operations: House of Representatives ................................................................... 2 8 Joint Items: Joint Economic Committee ......................................................... 10 14 Joint Committee on Printing ...................................................... 11 14 Joint Committee on Taxation .................................................... -

S. 724, S. 514, S. 1058, and H.R. 1294 Hearing Committee On

S. HRG. 110–686 S. 724, S. 514, S. 1058, AND H.R. 1294 HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 724, LITTLE SHELL TRIBE OF CHIPPEWA INDIANS RESTORATION ACT OF 2007 S. 514, MUSKOGEE NATION OF FLORIDA FEDERAL RECOGNITION ACT S. 1058, GRAND RIVER BANDS OF OTTAWA INDIANS OF MICHIGAN REFERRAL ACT H.R. 1294, THOMASINA E. JORDAN INDIAN TRIBES OF VIRGINIA FEDERAL RECOGNITION ACT OF 2007 SEPTEMBER 25, 2008 Printed for the use of the Committee on Indian Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 46–266 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 08:00 Apr 06, 2009 Jkt 046266 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\DOCS\46266.TXT JACK PsN: JACKF COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota, Chairman LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska, Vice Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona KENT CONRAD, North Dakota TOM COBURN, M.D., Oklahoma DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri RICHARD BURR, North Carolina JON TESTER, Montana ALLISON C. BINNEY, Majority Staff Director and Chief Counsel DAVID A. MULLON JR., Minority Staff Director and Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 08:00 Apr 06, 2009 Jkt 046266 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\DOCS\46266.TXT JACK PsN: JACKF C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on September 25, 2008 .................................................................... -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E363 HON

March 12, 1998 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E363 My bill will award grants to local school dis- sanitize, deodorize and conceal them. No bet- Fund. The Reverend Leon Edwards was tricts and teacher training programs that de- ter than our animal friends, we cannot escape called as the fourth pastor in July, 1974. Rev- velop alternative routes to certification pro- certain realities of our existence from birth to erend Edwards served with much pride and grams that open the teaching profession to in- decay. Indignity is inescapable. commanded the respect of all. Under the lead- dividuals with professional experience who ``There are moments so undignified that no ership of Reverend Edwards, Southwestern have the desire to teach. one dares peak of them in casual conversa- was able to complete the construction of its My bill will empower local school districts tion or popular entertainment. Commercials new church facility. On January 27, 1997, God that are facing teacher shortages or subject- show people with forks or beverages, but rare- called Reverend Edwards home to rest. area shortages to develop bold and innovative ly eating or drinking, because chewing and The Reverend Dwight D. Craig, assistant programs that recruit and prepare these highly swallowing are not pretty. Eating is not glam- Pastor under Reverend Edwards was installed qualified individuals to teach in our elementary orous. Neither is sneezing, scratching, hiccup- as the fifth pastor of Southwestern on June and secondary schools. ing, burping, nose blowing, acne, giving birth, 29, 1997. Reverend Craig has continued to These individuals could include education and other acts that I cannot even mention. -

Where Business Works

GREATER Fort Lauderdale Where Business Works Employers seeking the ideal combination of an abundant labor pool, targeted training and world-class education, a business-friendly market, robust culture and unmatched lifestyle for all ages, will find their next-generation workplace in Greater Fort Lauderdale. BY JEFF ZBAR AS FEATURED IN THE MAGAZINE OF FLORIDA BUSINESS GREATER Fort Lauderdale n 1971, Kevin Koenig opened life sciences, manufacturing and ❝We have his first Waterbed City location, a technology sectors. a great Imodest, 800-square-foot storefront Construction workers are building environment on Commercial Boulevard in east Fort some 6,500 hotel rooms and condo- Lauderdale. Thirty years later, Kevin minium residences countywide. to conduct and brother Keith looked west to Tourism continues to grow, as does the business ... Tamarac to open a 660,000-square-foot world-renowned marine industry, which headquarters, distribution center and employs thousands and generates but on the other showroom for what had evolved into City about $9 billion in annual revenues, side, we are a Furniture, the region’s largest furniture including $50 million in economic community that retailer. impact from the annual Seminole Hard The two sites — one near the Atlantic, Rock Winterfest Boat Parade. offers a lot for your the other on the edge of the Everglades Business leaders and area executives workforce.” — were separated by 10 miles and three credit the area’s kindergarten through decades of dynamic business growth. postgraduate educational system ∼Bob Swindell President and CEO “When we started, Commercial for nurturing and training a skilled Greater Fort Lauderdale Boulevard was a two-lane road and blue- and white-collar workforce.