CALICUT UNIVERSITY RESEARCH JOURNAL Vol 7 Issue 2 September 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constituent Assembly of India Debates (Proceedings) - Volume Xi

CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA DEBATES (PROCEEDINGS) - VOLUME XI Thursday, the 24th November, 1949 -------------- The Constituent Assembly of India met in the Constitution Hall, New Delhi, at Ten of the Clock, Mr. President (The Honourable Dr. Rajendra Prasad) in the Chair ------------- TAKING THE PLEDGE AND SIGNING THE REGISTER Mr. President : I understand some new Members have come--Members from Vindhya Pradesh. They have to take the pledge now and sign the register. The following Members took the Pledge and Signed the Register:- 1. Captain Awadesh Pratap Singh 2. Shri Shambu Nath shukla United State of 3. Pandit Ram Sahai Tewari Vindhya Pradesh 4. Shri Mannulalji Dwivedi -------------- DRAFT CONSTITUTION-(Contd.) Mr. President: We are now to resume discussion of the Draft Constitution. I desire to point out to honourable Members that although 77 Members have so far spoken on the motion of Dr. Ambedkar, I have got 54 names still on the list and we have only this day and perhaps one hour tomorrow for this purpose. So all these Members cannot possibly be accommodated within these six hours or 6 ½ hours if they speak at the rate other Members have spoken and I leave it to them either to take as much time as they like and deprive others of the opportunity of speaking or simply to come forward, speak a few words so that their names may also go down on record and let as many of others as possible get an opportunity of joining in this. Shri Guptanath Singh (Bihar: General): Sir, I want to make a suggestion. It seems a large number of Members are eager to speak. -

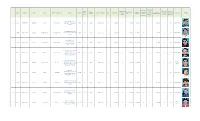

ADIP Beneficiary Data 2017-18

Boarding Travel cost Age / Fabrication/ and No. of days whether Monthly Total Cost of Subsidy paid to out Totel of State District Date Name Father's / Husband's Address Gender Birth Type of Aid Given Qty. Cost of Aid Fitment Loadging for which accompanie Category PHOTO Income Aid Provided station (12+13+14+15) Year Charge Expences stayed d by escort beneficiary paid Puthenpeedika, Tana, 1 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Nuhman Muhammed Pullippadam, Malappuram- Male 16 2,666 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) 676542 Nediyapparambil House, 2 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Akshay Dev V K Damodaran N P Nilambur Post, Malappuram- Male 17 3,500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) 679329 Veluthedath House, Vadakkumpadam Post, 3 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Akshaya K R Radhakrishnan Female 16 4000 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) Vandoor, Nilambur, Malappuram Panthalingal, Kaattumunda, Pallippad, Naduvath, 4 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Aslah P Mustafa P Male 12 2,500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) Mambad Village, Thiruvali, Malappuram-679328 Cheenkanniparackal, Kattmunda, Naduvath Post, Christian 5 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Sneha Philipose Philipose Female 17 4000 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Vandoor Village, Thiruvali, General Malappuram-679328 Palakkodan, Chenakkulangara, Naduvath 6 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Linju P Narayanan Female 14 1500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 -

Diet 3-54.Pmd

ISSN : 2321-3957 Edu - Reflections March 2015 CONTENTS Editors’ note Titles Page No TRAINING COMMUNICATORS Bereket Yebio....................................................................................................................................................... ..... 1-4 SOCIAL EXCLUSION AND MANIFESTATIONS OF INEQUALITY: A REFLECTION ON THEORIES AND A CASE Dr. Sreekala Edannur ......................................................................................................................................................... 5-10 A STUDY OF GIRLS’ EDUCATION IN RELATION TO AWARENESS AND PERCEPTION OF PARENTS AND TEACHERS Dr. Javed Akhtar ............................................................................................................................................................... 11-17 INTEGRATING CLASSROOM DRAMA INTO ENGLISH CLASSROOM Dr. K.M. Unnikrishnan .................................................................................................................................................... 18-22 PROBLEMS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PRE- PRIMARY EDUCATION IN THE TRIBAL SETTLEMENT OF PALAKKAD DISTRICT M.Shaheed Ali & K.Mohamed Basheer........................................................................................................................... 23-27 TEACHING COMPETENCE OF SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHERS IN RELATION TO THEIR ATTITUDE TOWARDS TEACHING PROFESSION Dr.M.G.Remadevi ............................................................................................................................................................ -

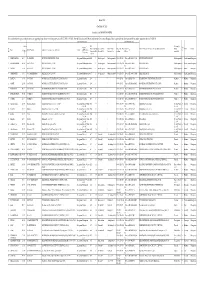

Accused Persons Arrested in Malappuram District from 10.12.2017 to 16.12.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Malappuram district from 10.12.2017 to 16.12.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 416/17 U/s Lashkkarmuhalla,H 11(1)(d) 13-12- 30/17 N pura,, Prevenction MALAPPU Binu,SI of BAILED BY 1 Amjath khan Nasar khan Malappuram 2017 at Male BAGALKOT, of Cruelty to RAM police POLICE 11:00 KARNATAKA Animals Act 1960 416/17 U/s Gousiya 11(1)(d) Nagar,Hydarali 13-12- Sayyid Sajith 45/17 Prevenction MALAPPU Binu,SI of BAILED BY 2 Block,Mysoor, Malappuram 2017 at mussammal Ismayil Male of Cruelty to RAM police POLICE MYSORE CITY, 11:00 Animals Act KARNATAKA 1960 Varikkodan (H), Downhill P.O, 16-12- 420/17 U/s 59/17 MALAPPU Binu,SI of BAILED BY 3 Basheer kunchimma Malappuram, malappuram 2017 at 119(a) of KP Male RAM police POLICE MALAPPURAM, 20:00 Act KERALA Brahmani Parambil house, Jugunu Haridasan, SI 10-12- 28/17 U/s 65/17 House, Vellilakkad, of BAILED BY 4 Devadas Appukkuttan Vengara 2017 at 406, 498 (A), VENGARA Male Tirurangadi, Police,Vengar COURT 13:00 34 IPC MALAPPURAM, a KERALA Areethalakkal House, Chenakkal, Abdul 10-12- 35/17 Valiyora P.O, Oorakam, 275/17 U/s Hakkim.K, BAILED BY 5 Shafeeque Kunheethu 2017 at VENGARA Male Vengara, Kunnath 151 CrPC SHO, Vengara POLICE 22:40 MALAPPURAM, PS KERALA Edayadan House, Abdul Changuvetty, 12-12- 161/17 U/s 32/17 Hakkim.K, BAILED -

Most Eminent Indian Women Who Contributed to the Constitution of India

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Written & Conceptualized by: Bonani Dhar Development Sociologist, Gender & Human Resource Specialist Ex-World Bank & UN Adviser CDGI, Students & Faculty Development Cell & Chairperson WDC Phone: 9810237354 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Most Eminent Indian Women who contributed to the Constitution of India The Constitution of India was adopted by the elected Constituent Assembly on 26 November 1949 and came into effect on 26 January 1950. The total membership of the Constituent Assembly was 389. While we all remember Dr. B R Ambedkar as the Father of the Constitution and other pioneering male members who helped draft the Indian Constitution, the contribution of the fifteen female members of the Constituent Assembly is easily forgotten. On this Republic Day, let’s take a look at the powerful women who helped draft our Constitution. 1. Ammu Swaminathan Image Credit: The Indian Express Ammu Swaminathan was born into an upper caste Hindu family in Anakkara of Palghat district, Kerala. She formed the Women’s India Association in 1917 in Madras, along with Annie Besant, Margaret Cousins, Malathi Patwardhan, Mrs Dadabhoy and Mrs Ambujammal. She became a part of the Constituent Assembly from the Madras Constituency in 1946. In a speech during the discussion on the motion by Dr B R Ambedkar to pass the draft Constitution on November 24, 1949, an optimistic and confident Ammu said, “People outside have been saying that India did not give equal rights to her women. Now we can say that when the Indian people themselves framed their Constitution they have given rights to women equal with every other citizen of the country.” She was elected to the Lok Sabha in 1952 and Rajya Sabha in 1954. -

Consumer Grievance Redressal Forum Northernregion Present

CONSUMER GRIEVANCE REDRESSAL FORUM NORTHERN REGION, KOZHIKODE. (Formed under section 42(5) of Electricity Act 2003.) Vydyuthibhavan, Gandhi Road, Kozhikode -673011 Telephone Number -0495 2367820 [email protected] PRESENT MEENA. S : CHAIRPERSON MANOJAN .P.P : MEMBER II ROBIN PETER : MEMBER III OP NO. 14/2018-19 PETITIONER : 1. Sri. Arun.R.Chandran, Authorized Signatory, M/s. Indus Towers Ltd., 8th Floor, Vankarath Towers, Palarivattom, Cochin – 24. RESPONDENTS : 1. Assistant Executive Engineer, Electrical Sub Division, KSEB Ltd, Kalikavu, Malappuram District – 676 525. 2. Assistant Engineer, Electrical Section, KSEB Ltd., Tuvvur, Malappuram District 679 327. ORDER Case of the Petitioner:- The petition is filed by the representative of M/s.Indus Towers ltd, a company meant for providing passive infrastructure to the telecommunication service providers .The company have more than 6000 tower sites all over kerala with KSEB Supply and the current charges remitted by the company comes around Rs.30 crore per month. The petitioner applied for an electric connection having connected load of 8 KW to the mobile tower site at Chembrassery under electrical section Thuvvur on 13/12/2016, remitting the required application fee. It is alleged that the Assistant Engineer snubbed their repeated requests for providing electric connection. Later, the licensee served a reply dated 16/02/2017 stating that the transformer feeding the area under the site is working at its maximum capacity and it is not possible to accommodate additional load. Therefore service connection cannot be provided for the requested load of 8 KW. The petitioner states that the site is running with Diesel Generator set and the company is suffering from a huge financial loss due to the above. -

Unsung Voices and Unregistered Memories of Malabar Rebellion: a Case Study of Erstwhile Malabar

Research Journal of Kisan Veer Mahavidyalaya, Wai (A Multilingual and Multi-disciplinary Research Journal) Issue-3, Vol.- 1, PP- 47-51 Jan-June, 2019 Unsung voices and Unregistered Memories of Malabar Rebellion: A Case Study of Erstwhile Malabar *Anita M. Department of History, N.S.S.College, Manjeri, Malappuram (Kerala) Abstract: Malabar rebellion must be reckoned as a turning point in the modern history of Kerala and a significant event in the history of India. It was mainly a revolt of the mappila population mainly peasants “against the lord and state” .The mass insurrection lasted for about 8 months and proved to be a more violent and devastating than any other earlier out breaks. The rebellion was a bloody and traumatic experience for the whole population of Malabar. The army and police unleashed a reign terror; both men and women became the victims of the terror. The present paper aims to bring out the views and comments of the people regarding the anti- colonial and anti- land lord struggle. The people who didn‟t have a direct experience of the rebellion also framed a view of the struggle through the tales and stories passed through the generations. An oral history is an account of information that has been passed down through the generation. An oral report must be a true description of an event. In collection of oral testimony historian should be sensitive to gender differences. The answer provided by male and female may not be alike. Women do have their own style and tools (Language, gestures, expressions etc.) to recall the tale of day to day life in the past and how the event affected the personnel life of their as well as their immediate relatives. -

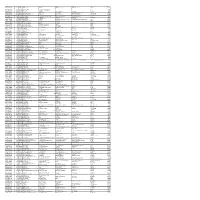

Palakkad PALAKKAD

Palakkad PALAKKAD / / / s Category in s s e e Final e Y which Y Reason for Y ( ( ( Decision in 9 his/her 9 Final 9 1 1 appeal 1 - - house is - Decision 6 3 1 - - (Increased - 0 included in 1 (Recommen 1 3 3 relief 3 ) ) ) Sl Name of disaster Ration Card the Rebuild ded by the Relief Assistance e e o o o e r Taluk Village r amount/Red r N N N o No. affected Number App ( If not o Technically Paid or Not Paid o f f f uced relief e e in the e Competent b b b amount/No d Rebuild App d Authority/A d e e e l l change in a Database fill a ny other m e e i relief p p the column a reason) l p p amount) C A as `Nil' ) A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1 Palakkad Akathethara T M SURENDREN 1946162682 yes Paid 2 Palakkad Akathethara DEVU 1946022862 yes Paid 3 Palakkad Akathethara PRASAD K 1946022923 yes Paid 4 Palakkad Akathethara MANIYAPPAN R 1946022878 yes Paid 5 Palakkad Akathethara SHOBHANA P 1946021881 yes Paid Not Paid 6 Palakkad Akathethara Seetha 1946022739 yes Duplication 7 Palakkad Akathethara SEETHA 1946022739 yes Paid 8 Palakkad Akathethara KRISHNAVENI K 1946158835 yes Paid 9 Palakkad Akathethara kamalam 1946022988 yes Paid 10 Palakkad Akathethara PRIYA R 1946132777 yes Paid 11 Palakkad Akathethara CHELLAMMA 1946022421 yes Paid Page 1 Palakkad 12 Palakkad Akathethara Chandrika k 1946022576 yes Paid 13 Palakkad Akathethara RAJANI C 1946134568 yes Paid KRISHNAMOORT 14 Palakkad Akathethara 1946022713 yes Paid HY N 15 Palakkad Akathethara Prema 1946023035 yes Paid 16 Palakkad Akathethara PUSHPALATHA 1946022763 yes Paid 17 Palakkad Akathethara KANNAMMA -

MALAPPURAM District, Kerala

Coconut Producers Federations (CPF) - MALAPPURAM District, Kerala Sl No.of No.of Bearing Annual CPF Reg No. Name of CPF and Contact address Panchayath Block Taluk No. CPSs farmers palms production AREACODE PANJAYATH FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri Sadikali P 1 CPF/MPM/2014-15/065 Areacode Areacode Eranad 8 361 40929 2700474 Kaithayil House, Near I.T.I., Ugrappuram P.O Pin:673639 Mobile:9846612772 NARAGIL FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS 2 CPF/MPM/2015-16/089 SOCIETIES President: Shri A P Muhammed A.P.B Areacode Areacode Eranad 8 702 40003 2055765 House, Areecode, Areecode PO Pin:673639 CHEEKODE GRAMA PANCHAYATH FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri 3 CPF/MPM/2012-13/015 Cheekode Areacode Eranad 19 1292 81524 10198245 Sainudheen K P Puiyamakal House, Cheriayaparambu P.O., Vilayil, Malapuram Pin:673641 Mobile:9846162666 EDAVANNA GRAMA PANCHAYAT FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri K 4 CPF/MPM/2013-14/029 Edavanna Areacode Eranad 10 653 41348 3424275 Muhammed Kallingal (H), Edavanna (PO), Malappuram Pin:676541 Mobile:9895224606 ERANAD FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCING SOCIETY President: Shri Ahammed Kutty Athikkal 5 CPF/MPM/2014-15/079 Edavanna Areacode Eranad 13 854 56689 3673770 House, Kunnummal, Edavanna PO Pin:676541 Mobile:9946274616 KAVANUR GRAMA PANCHAYAT FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri M P 6 CPF/MPM/2013-14/030 Kavannur Areacode Eranad 14 908 59559 6601335 Saidalavi Panampattachalil (H), Erivetty (PO), Kavanur, Malappuram Pin:673639 Mobile:9446215455 -

Archive: Biographical Essays Women Politicians of Constituent Assembly Ammu Swaminathan (1894-1978)

ARCHIVE: BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAYS WOMEN POLITICIANS OF CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY AMMU SWAMINATHAN (1894-1978) EARLY LIFE: Ammukutty, as she, Ammu Swaminathan, was fondly called, was born in the Anakkara Vadakkath family to Govinda Menon and Anakkara Vadakath Ammuamman, in Palghat (Palakkad) district of Kerala in 1894. Her father was a minor local official earning what was only sufficient for a hand to mouth existence for her whole family. Both of Ammu's parents belonged to the Nair caste, and Ammu was the youngest of their numerous children. However, despite their family’s financial struggles, Govinda Menon and Anakkara focussed on getting all their children educated, including their daughters. Hence, Ammu was not deprived of her right to study, though she received an informal education at home. However, things started worsening when Ammu lost her father, the only breadwinner of their large household, at a very young age. She saw her mother struggling to run their expenses. Consequently, Ammu could not receive the quality education which she was entitled to, for some time. Nevertheless, Ammu was a spirited girl. At the age of 13 when faced with the prospect of marriage, she laid down her own conditions before agreeing to it. Her husband, Subbarama Swaminathan was a close associate of her father P. Govinda Menon and had expressed his desire to marry one of his daughters upon completion of his higher education in England. By that time, Menon had passed away and all his daughters except for the 13-year-old Ammu were married. So, when Swaminathan, a man twenty years her senior, proposed marriage to the young Ammu, he was confronted with a strange situation. -

Form 19 a (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List( GROUP B- PART-I) It

Form 19 A (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List( GROUP B- PART-I) It is certified that the persons whose names are appering in this list are tested as positve as on 07/12/2020 15:13:01 (Date & Time) for covid 19 infection by the Government Hospital/Lab recognized by the Government OR are under quarantine due to COVID 19 ELECTION DETAILS ID CARD DETAILS Gender GP/ Municpality / Name of Ward Sl Municipal / Ward Name of Block Name of Dist Electoral roll Part Name of Address of the present location of hospitalisation/ quarantine Grama Taluk District Name Age Father/ Husband Address for communication with Pincode District GP/Municipal / No No No /M / F Corporation No Divsion & No Divsion & No no Sl no ID card panchayath Corporation /T serial No 1 UMMUHABEEBA 28 F W/o IBRAHIM KINATTINGATHODI HOUSE, 679324 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 7 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo104 Election KL/06/041/333355 KINATTINGATHODI HOUSE Makkaraparamba7 PerinthalmannaMalappuram Id 2 RAMAKRISHNAN 69 M S/o CHANTHU PALLIYALIL HOUSE, 676507 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 3 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo720 Election HFS1508183 PALLIYALIL HOUSE Makkaraparamba3 PerinthalmannaMalappuram Id 3 SAJITHA 35 M W/o RAJEEV PALLIYALIL HOUSE, 676507 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 3 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo723 Election HFS2389799 PALLIYALIL HOUSE Makkaraparamba3 Eranad Malappuram Id 4 PRABHAVATHI 54 F W/o RAMAKRISHNAN PALLIYALIL HOUSE, 676507 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 3 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo721 Election KL/06/041/330228 -

Mgl- Int 4-2015 Unpai D Shareholders List As on 30-06

FOLIO-DEMAT ID NETDIV DWNO NAME ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 City PIN 1201910100545543 45.00 15410593 DIVESH SACHDEVA T - 2638, HARDHYAN SINGH MARG FAIZ ROAD, KAROLBAGH NEW DELHI 110005 1203320007146634 270.00 15410949 MOHINDER KAUR B-162 I FLOOR FATEH NAGAR DELHI 110018 1203460000333748 516.00 15411360 SURESH BAID 91, SAINIK VIHAR PITAM PURA DELHI 110034 IN30159010007933 23.00 15411460 S.M.JAIN H.NO.895, GALI JAIN MANDIR, NAJAFGARG, NEW DELHI 110043 1204470000418754 45.00 15412114 AMIT TIWARI UPKAR COLONY HOUSE NO B-2/1 OPP BURARI GOVT SCHOOL BURARI DELHI 110084 IN30236510644395 208.00 15413996 AJAY KUMAR SHARMA H.NO.- D-10, SANJAY NAGAR, SECTOR-23, GHAZIABAD, UTTAR PRADESH 201001 1203320004195371 32.00 15412280 KANNATH SUKUMARAN NAIR 159 C BLOCK B S SHALIMAR BAGH NEW DELHI 110088 1203200000001219 225.00 15412326 SAROJ SAXENA . B-70, GALI NO.10, SASHI GARDEN NEELKANTH APARTMENT MAYUR VIHAR, PHASE - 1 DELHI 110091 IN30133017791439 1.00 15413742 NISCHAL ARORA H.NO 399 FIRST FLOOR SECTOR 20 A, CHANDIGARH 160019 IN30036021965318 45.00 15414219 KIRTI RAJ SINGH B 644 SAINIK COLONY SECTOR 49 FARIDABAD 201301 IN30177416845663 45.00 15414341 POOJA SINGHAL H NO 349 STRT MAMOORA GANV VILL MAMOORA POLICE STN SEC 58 GAUTAM BUDH NAGAR NOIDA 201307 IN30105510700089 118.00 15414529 DAYA SHANKER SHUKLA 10/175 KHALASI LINE KANPUR 208002 IN30254010005948 45.00 15413998 VINOD KUMAR SHARMA 231 MIRZAZAN DASNA GATE GHAZIABAD 201001 1206140000059951 45.00 15414540 MANOJ KUMAR SINGH 86/243 RAI PURWA KANPUR 208003 IN30001110703000 135.00 15414611 MAN MOHAN SINGH