© Copyright 2021 Kyle Kubler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack Lalanne and the Modernization of Fitness Fitness in America Then Fitness in America Now PART TWO: RESHAPE Chapter 3: Boomers

If You Want to Live, Move! Putting the Boom Back into Boomers Elaine LaLanne Jaime Brenkus Table of Contents FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION PART ONE: RENEW Chapter 1: BOOMERS. Begin Anew Bring Back your Boom Back to the Basics Chapter 2: BOOMERS. Defined Jack LaLanne and the Modernization of Fitness Fitness in America Then Fitness in America Now PART TWO: RESHAPE Chapter 3: Boomers. Moving Your Body Muscle Loss in Boomers Boomer Facts 8 Minutes at a Time Be Grateful and Happy The Story of Ike & Mike Chapter 4: BOOMERS. Time is on Your Side Daily Victories Watch your ‘Negative’ Language Chapter 5: BOOMERS. A Selfie and a Tape Measure Afterburn Effect How to choose your weights Take the Talk test Heart Rate Check Be Consistent Rethink Your Definition of Exercise Fitness RX Routine to Lean Chapter 6: BOOMERS. Early Morning Secrets of Jaime and Elaine Elaine’s Magic 5 Wake Up Exercises Jaime’s FIT 3 7 Days Without Fitness Makes One Weak Increase Your Muscle Mass Chapter 7: BOOMERS. The Daily 8 Fitness Fusion Ageless Energy and Timeless Health Exercises Day 1 Fast Fitness Day 2 Strength Aerobics Day 3 Floor Fitness Day 4 Chair Fitness Day 5 Fitness Fusion PART THREE: REFUEL Chapter 8: BOOMERS. Eat in Moderation Moderation is Key Portion Power The “Jaime Brenkus eyeball” method Snacks Putting the “New” in Nutrition The Downsize Cut Calories, Shed Pounds How to Cut 100 Calories Lean Ways to Slash and Smash Calories Clean Plate Club 80/20 Lean Cart Protien Sugar Healthy “Whole Unrefined” Carbs Not So Healthy “Refined” Carbs Chapter 9: BOOMERS. -

Music Recommendation Algorithms: Discovering Weekly Or Discovering

MUSIC RECOMMENDATION ALGORITHMS Music Recommendation Algorithms: Discovering Weekly or Discovering Weakly? Jennie Silber Muhlenberg College, Allentown, PA, USA Media & Communication Department Undergraduate High Honors Thesis April 1, 2019 1 MUSIC RECOMMENDATION ALGORITHMS 2 MUSIC RECOMMENDATION ALGORITHMS Abstract This thesis analyzes and assesses the cultural impact and economic viability that the top music streaming platforms have on the consumption and discovery of music, with a specific focus on recommendation algorithms. Through the support of scholarly and journalistic research as well as my own user experience, I evaluate the known constructs that fuel algorithmic recommendations, but also make educated inferences about the variables concealed from public knowledge. One of the most significant variables delineated throughout this thesis is the power held by human curators and the way they interact with algorithms to frame and legitimize content. Additionally, I execute my own experiment by creating new user profiles on the two streaming platforms popularly used for the purpose of discovery, Spotify and SoundCloud, and record each step of the music discovery process experienced by a new user. After listening to an equal representation of all genre categories within each platform, I then compare the genre, release year, artist status, and content promotion gathered from my listening history to the algorithmically-generated songs listed in my ‘Discover Weekly’ and ‘SoundCloud Weekly’ personalized playlists. The results from this experiment demonstrate that the recommendation algorithms that power these discovery playlists intrinsically facilitate the perpetuation of a star- driven, “winner-take-all” marketplace, where new, popular, trendy, music is favored, despite how diverse of a selection the music being listened to is. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Move to Be Well: the Global Economy of Physical Activity

Move to be Well: Mindful Movement The Global Economy of Equipment & Supplies Physical Activity Technology Fitness Sports & Active Apparel & Recreation Footwear OCTOBER 2019 Move to be Well: The Global Economy of Physical Activity OCTOBER 2019 Copyright © 2019 by the Global Wellness Institute Quotation of, citation from, and reference to any of the data, findings, and research methodology from this report must be credited to “Global Wellness Institute, Move to be Well: The Global Economy of Physical Activity, October 2019.” For more information, please contact [email protected] or visit www.globalwellnessinstitute.org. CONTENTS Executive Summary i Full Report 1 I. Physical Inactivity: A Rising Global Crisis 3 Physical activity is essential to health, and yet, collectively we have become 3 more inactive. How did we become so inactive? 4 Physical activity versus fitness: A privilege, a choice, or a right? 5 II. Understanding the Economy of Physical Activity 7 Defining physical activity 7 The evolution of recreational and leisure physical activity 9 The economy of physical activity 12 What does this study measure? 14 III. The Global Physical Activity Economy 21 Physical activity global market 21 Recreational physical activities 25 • Sports and active recreation 29 • Fitness 34 • Mindful movement 41 Enabling sectors 48 • Technology 49 • Equipment and supplies 55 • Apparel and footwear 56 Physical activity market projections 57 IV. Closing Physical Activity Gaps and Expanding Markets 61 Physical activity barriers and motivations 61 Business innovations and public initiatives to overcome barriers 63 • Mitigating time constraints and increasing convenience 63 • Making physical activity a daily habit 65 • Making physical activity fun and appealing 69 • Enabling movement in all physical conditions 73 • Embedding physical activity in the built environment 75 • Making physical activity affordable and accessible to everyone 76 V. -

Download Bebe Rexha Album

download bebe rexha album SORINEL DE LA PLOPENI (Album 2021 Vol.2) Iti multumim ca ai accesat siteul nostru, aici gasesti cele mai noi melodii mp3, iti punem la dispozitie cea mai noua muzica din toate genurile muzicale, categoriile de baza fiind: manele , muzica romaneasca , muzica petrecere , muzica straina , muzica house , muzica trap dar si albume mp3 cat si videoclipuri in format HD. De ce sa ne alegi pe noi? Site-ul numarul #1 cand vine vorba de Muzica Noua Mp3. Simplu de folosit, acum cu un nou design usor de navigat si in varianta mobila. Descarci gratuit cea mai noua muzica in format mp3 si videoclipuri la o calitate HD rapid si sigur. Daca nu gasesti melodia pe site poti aplica o cerere care sa contina titlu si link youtube (valid) iar noi in maxim 24 ore adaugam melodia pe site. In momentul in care te-ai abonat, vei primi cele mai noi melodii adaugate pe website direct pe adresa ta de e-mail. ROMANIAN FRESH TRACKS - JUNE HITS 2021 (Hiturile Lunii Iunie) Iti multumim ca ai accesat siteul nostru, aici gasesti cele mai noi melodii mp3, iti punem la dispozitie cea mai noua muzica din toate genurile muzicale, categoriile de baza fiind: manele , muzica romaneasca , muzica petrecere , muzica straina , muzica house , muzica trap dar si albume mp3 cat si videoclipuri in format HD. De ce sa ne alegi pe noi? Site-ul numarul #1 cand vine vorba de Muzica Noua Mp3. Simplu de folosit, acum cu un nou design usor de navigat si in varianta mobila. Descarci gratuit cea mai noua muzica in format mp3 si videoclipuri la o calitate HD rapid si sigur. -

Coca-Cola Foundation's

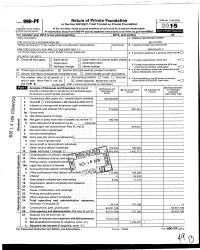

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation m 2015 numbers public. Department of the Treasury ► Do not enter social security on this form as it may be made ,)ntemal Revenue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www. irs.gov/form99opf. • For calendar year 2015 or tax year beainnina . 2015. and ending .20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE COCA-COLA FOUNDATION, INC 58-1574705 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) ONE COCA-COLA PLAZA, NW, C/O TAX DEPT NAT 11 404-676-8713 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► ATLANTA, GA 30313 q G Check all that apply: q Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q E] Address change E] Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization: 3q Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under section 507(b)(1)(A) , check here El Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust El Other taxable private foundation 1 q q Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part Il, col. -

Home Is Where the Art Is Developer Pulls AGHAHOWA Emotional Stories of His Create, He Said

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 SATURDAY, AUGUST 31, 2019 DEALS OF THE HOME IS WHERE $DAY$ THE ART IS PG. 3 DEALS OF THE Todd Baldwin $DAY$ PG. 3 Saugus hires an DEALS OF THE engineer ITEM FILE PHOTO Jessie Benton $FremontDAY$ spent her summer vacationsPG. 3 at a By Bridget Turcotte house on Willow Road in the ITEM STAFF 1860s. The owner of that house, SAUGUS — The town Molly Conlin, played the part of hired an engineer to study Jessie Benton Fremont in her and analyze the town’s in- living room at an annual Wom- frastructure. an’s Club meeting.DEALS Todd Baldwin has been OF THE appointed town engineer, a position created in 2018 ITEM PHOTO | SPENSER HASAK Nahant$ club$ to work with the Depart- From the back of a pick-up truck artist Michael Aghahowa speaks to the DAY ment of Public Works and crowd gathered in the Andrew Street Parking Lot about the meaning PG. 3 Planning Department to behind his mural that he painted on the wall of Zimman’s as part of the ‘stronger coordinate projects and 2019 Beyond Walls Street Art Festival. look at plans submitted by prospective developers By Bella diGrazia residents and we worked on the idea for to streamline the process. ITEM STAFF this piece together at the Gregg House, than ever’ Town Meeting approved where I basically grew up as a kid,” said $80,000 to fund the sala- LYNN — Lynn native Michael Agha- Aghahowa. “We’d always have conversa- ry of a town engineer in howa paints a bigger picture with his tions about the developments going up in at 125 2018, but Baldwin is the mural on Andrew Street. -

Arbitron-Rated Markets As of April, 2012 (NAB Reply

BEFORE THE jftbtral ~ommunitations ~ommission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) 2010 Quadrennial Regulatory Review - ) MB Docket No. 09-182 Review of the Commission's Broadcast ) Ownership Rules and Other Rules Adopted ) Pursuant to Section 202 of the ) Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) FILED/ACCEPTED ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No. 07-294 - In the Broadcasting Services ) II !I - ~ ?n1? Federal Communications Commission Office of the Secretary ADDENDUM TO MT. WILSON REPLY COMMENTS IN RESPONSE TO NAB REPLY COMMENTS PERTAINING TO LOCAL RADIO OWNERSHIP LIMITS The Comments and Reply Comments of the National Association of Broadcasters (hereinafter "NAB") propose the reformation of the radio ownership rule limits - presumably justified on the basis of competition from new audio platforms adversely affecting a segment of the NAB membership, group owners. The NAB arguments are supported only by self-serving verbiage. The single exhibit offered in support of reformation (NAB Reply Comments, Attachment B) bears no relevance to the alleged adverse impact on group owners. The primary purpose of this Addendum is to emphasize the folly of NAB Comments/Reply Comments dependent solely on unsupported verbiage and to explicitly make clear that the NAB filings do not represent the interests of the entire NAB membership, do not represent the interests of the independent broadcaster. ) I. The NAB Filings are Primarily Noteworthy for the Omission of Relevant Documentation In Support Of the Arguments: for the Failure to Rebut Documentation That Disproves the NAB Unsupported Arguments and for the Failure to Consider New Positive Factors Beneficial to the Radio Industry A. Failure to provide documentation in support of assumed adverse affect and failure to rebut Mt. -

Singer Family Has Legacy of Giving Manchester Hebrew Cemetery

Published by the Jewish Federation of New Hampshire Volume 38, Number 9 July 2018 Tammuz-Av 5778 Legacy Awards: Singer Family Has Legacy of Giving Shlicha Noam Wolf By Michael Cousineau "They have set an example for others to Bring Prayers & to follow," Baines said. Reprinted with permission of New Three of Irving's seven children (along Wishes From New Hampshire Union Leader with a son-in-law) currently own Merchants Hooksett — Decades ago, Irving Sing- Automotive Group. Their 93-year-old Hampshire to the er would bring home college students mother, Bernice, still lives in Manchester. and others in need of a hot meal after The Granite State Legacy Awards cele- Western Wall! synagogue on Saturdays. brate the accomplishments of the state's Manchester — Jewish Federation of "My mom always knew to set an extra most distinguished citizens who have giv- New Hampshire is excited to announce a five or six settings for people who didn't en the most to New Hampshire through special opportunity for the statewide have a warm meal," son Gary Singer re- business, philanthropy, politics, and more. Jewish community. Our Shlicha, Noam called last week. The awards are given to New Hampshire Wolf, is returning to Israel to visit family The gesture was part of a legacy of residents who have made significant con- and friends before the second year of her giving -- both public and private -- by the tributions over an extended period to their Shlichim begins. In an effort to bring us Singer family over the past half century. Gary Singer talks about awards he has profession, community, and state. -

Identity Formation and Well-Being in Lgbt Community Bands

IDENTITY FORMATION AND WELL-BEING IN LGBT COMMUNITY BANDS by NICHOLAS D. SOENYUN A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music June 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Nicholas D. Soenyun Title: Identity Formation and Well-Being in LGBT Community Bands This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Music degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Jason M. Silveira Chairperson Dr. Beth Wheeler Member Dr. Melissa Brunkan Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2019 ii © 2019 Nicholas D. Soenyun iii THESIS ABSTRACT Nicholas D. Soenyun Master of Music School of Music and Dance June 2019 Title: Identity Formation and Well-Being in LGBT Community Bands The purpose of this study was to determine what relationships exist, if any, between psychological well-being, psychosocial well-being, internalized homonegativity (IH), and LGBT community band participation, as well as to holistically investigate these constructs, with identity formation, through participant experiences. Participant responses to survey data (N = 100) were analyzed via Pearson correlation. Significant relationships emerged between psychological and psychosocial well-being (r2 = .12), as well as between psychological well-being and IH (r2 = .05) at both the p < .01 and p < .05 levels, respectively. No significant relationships were found between any of the constructs with years of participation, or between psychosocial well-being and IH. -

Book Chapter Reference

Book Chapter Street workout, savoir kinésique et vidéos en ligne BOLENS, Guillemette, MUELLER, Alain Reference BOLENS, Guillemette, MUELLER, Alain. Street workout, savoir kinésique et vidéos en ligne. In: Del Valle, M., Maurmayr, B., Nordera, M., Paillet, C. & Sini, A. Pratiques de la pensée en danse : les Ateliers de la danse. Paris : L’Harmattan, 2020. p. 93-111 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:140138 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 La collection du CTEL Université Nice Sophia Antipolis Licence accordée à Bolens Guillemette [email protected] - ip:92.106.50.191 14 Pratiques de la pensée Pratiques de la pensée en danse en danse Les Ateliers de la danse Ce volume réunit les résultats d’un processus collectif engagé depuis une Les Ateliers de la danse quinzaine d’années par l’équipe des chercheur·e·s en danse de l’Université Côte d’Azur. Au fil des pages, se dépose et s’actualise la mémoire des pratiques de la pensée qui ont animé les Ateliers de la danse, manifestation scientifique inaugurée en 2005 en partenariat avec le Festival de danse de Cannes, et arrivée en 2019 à sa neuvième édition. La structure du volume découle des temps forts de ce processus collectif. La première partie, « Écrire en corps », analyse les usages des écritures, des notations et de la description chorégraphique ; elle explore les espaces qu’elles ouvrent (ou ferment) pour la recherche en danse. La deuxième partie s’intéresse aux notions qui caractérisent « Le(s) temps de la danse » dans la recherche et la création selon des approches musicale, historique, anthropologique et poïétique. -

Convict Conditioning Series

Mobile Fitness—Take It With You Dear Fellow Health and Strength Enthusiast, Dragon Door y good friend Dan John and I were Publications presents talking the other day about what HardStyle M Dragon Door excelled in. Dan came up www.dragondoor.com with a brilliant phrase: “Backpack Fitness.” I love that! It perfectly encapsulates what we best stand Publisher & Editor-in-Chief John Du Cane for. And I’ve just thought of a matching phrase: “Mobile Fitness.” It’s really who we are and what Design we are all about! Derek Brigham www.dbrigham.com Let’s take kettlebells for instance, which we Dragon Door Corporate introduced to America first in 2001. We billed Customer Service call 651-487-2180 or email them as the “handheld gym”—and that is exactly [email protected] what they are. Who needs bulky equipment, gerbil-machines and gym memberships when you Orders & Customer Service on Orders: can get all your strength and conditioning needs calisthenics training resource you could possibly call 1-800-899-5111 handled with one simple tool? Now you can be need to optimize your performance and well- anywhere, go anywhere and bust out your reps Dragon Door Publications being. corporate address: for a total workout. And 30 minutes or less is all Dragon Door Publications you need to get the results you want. Home, office, Now, no exercise program in the world—Naked 5 County Road B East, #3 park—you name it—the kettlebell will be there for or otherwise—is safe without a sensible, science- Little Canada, MN 55117 you.