North America's Shifting Supply Chains: the USMCA, COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-47 Main Text Final ISJ47.Indd 1 04/06/2010 21:08 Contents Continued

May/Jun 2010 Volume 7 No. 47 Investor Services Annual membership GBP 249 - UK, ROW Journal USD 379 - America ISJ EUR 286 - EMEA www.ISJ.tv THE GLOBAL CUSTODY AND ASSET SERVICING INDUSTRY MAGAZINE Under the microscope, UCITS - the workings European Custody - 2011 Guide Mark Mobius - ISJ Profile Corporate Actions - XBRL, Swift and DTCC WWW.ISJ.tv Barclays Exits - African custody Front Cover Section ISJ47.indd 1 03/06/2010 20:37 Bottom line: Your securities services expert 2in Central and Eastern Europe @ Our network is available for you in Central and Eastern Europe for your securities services business. We bring you in-depth local experience and award winning international expertise. ING is your partner in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovak Republic and Ukraine. For more information call Lilla Juranyi, Global Head of Custody, on +31 20 7979435 or e-mail: [email protected]. www.ingcommercialbanking.com ING Commercial Banking is a marketing name of ING Bank N.V., registered by the Netherlands Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). Copyright ING Commercial Banking (2010). FrontISJ47 Covercomplete Section text.indd ISJ47.indd 15 2 03/06/201027/05/2010 20:3812:11 contents Heads Up May/Jun 2010 Volume 7 No. 47 Investor Services Annual membership GBP 249 - UK, ROW Journal USD 379 - America ISJ EUR 286 - EMEA www.ISJ.tv THE GLOBAL CUSTODY AND ASSET SERVICING INDUSTRY MAGAZINE Under the microscope, UCITS - the workings Investor Services ISJ Journal European Custody - 2011 Guide Mark Mobius - ISJ Profile Corporate Actions - XBRL, Swift and DTCC WWW.ISJ.tv Barclays Exits - African custody THE GLOBAL CUSTODY AND ASSET SERVICING INDUSTRY MAGAZINE Front Cover Section ISJ47.indd 1 03/06/2010 20:37 Editor Brian Bollen Welcome to a new look ISJ and welcome to new people on our own team as Brian [email protected] Bollen is appointed Editor of the journal, working with Roy Zimmerhansl our E-in-C, and Clive Gande chairs our new advisory board. -

Investing in Emerging and Frontier Markets

Investing in Emerging and Frontier Markets Investing in Emerging and Frontier Markets Edited by Kamar Jaffer E U R B O O M O O K N S E Y Published by Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC Nestor House, Playhouse Yard London EC4V 5EX United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7779 8999 or USA 11 800 437 9997 Fax: +44 (0)20 7779 8300 www.euromoneybooks.com E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC and the individual contributors ISBN 978 1 78137 103 9 This publication is not included in the CLA Licence and must not be copied without the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form (graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems) without permission by the publisher. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information with regard to the subject matter covered. In the preparation of this book, every effort has been made to offer the most current, correct and clearly expressed information possible. The materials presented in this publication are for informational purposes only. They reflect the subjective views of authors and contributors and do not necessarily represent current or past practices or beliefs of any organisation. In this publication, none of the contributors, their past or present employers, the editor or the publisher is engaged in rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax or other professional advice or services whatsoever and is not liable for any losses, financial or otherwise, associ- ated with adopting any ideas, approaches or frameworks contained in this book. -

Interview with Dr. J. Mark Mobius of Franklin Templeton Investments

Vol. V, No. 2 A Global View of the Closed-End Fund Industry March 2005 THE SCOTT LETTER is intended Interview with Dr. J. Mark Mobius to educate global investors about closed-end funds. Closed-end funds can be a valuable and of Franklin Templeton Investments profitable investment tool. To learn about closed-end funds, ark Mobius is one of the world’s leading International Advisors in Washington, D.C. visit our web site, emerging markets equity investors and joined us. www.CEFAdvisors.com, and in M particular, read our article, What is managing director of Templeton Asset SL: How have the emerging markets Are Closed-End Funds. Feel free Management Limited. He is responsible for changed since we talked to you last year? to forward this newsletter to over $14.8 billion of assets under management Mobius: They performed very well; this anyone who you believe could as of January 31, 2005. has created a positive environment. We have benefit from information on closed-end funds or global Dr. Mobius joined Templeton in 1987 as had a good run [in these markets]. Confidence portfolios. President of Templeton Emerging Markets is very high as indicated by the spread between – George Cole Scott Fund in Hong Kong. He currently directs the the U.S. markets’ sovereign debt and the U.S. Editor-in-Chief analysts in Templeton’s 11 emerging markets Treasuries. A few years back, it was as high as offices and manages the emerg- 14%, but it is now below 4%. ing markets portfolios, includ- The spread can be attributed to ing mutual funds and three what has happened in Brazil, closed-end funds for Franklin Mexico, Turkey and Russia. -

Sir John Templeton Investment Roundtable 2019 London | 16Th May About Oxford Metrica

Sir John Templeton Investment Roundtable 2019 London | 16th May About Oxford Metrica Oxford Metrica is a strategic advisory firm, offering informed counsel to boards. Our advisory services are anchored on evidence-based research in risk and financial performance. Our work includes statistical analysis and index construction for banks and insurers, risk and performance analytics for asset managers, due diligence support in mergers and highly customised services for corporate boards. Private and Confidential Copyright © John Templeton Foundation W Sir John Templeton Investment Roundtable 2019 London | 16th May contents The Participants 3 FOREWORD 4 Keynote Address BY DR MARK MOBIUS 5 Q&A with Dr Mark Mobius 9 America and China: THE THUCYDIDES TRAP? 12 Meltdown or Melt-Up? The Global Economy 15 Technology: Disruption through Concentration 18 Value Pockets and Value Traps: the Investment Outlook 20 stOCK SELECTIONS 24 2 The Participants Moderator Dr. Rory Knight, Chairman, Oxford Metrica; Trustee, JTF & TWCF KEYNOTE SPEAKER Dr Mark Mobius, Founder, Mobius Capital Partners Investment Managers Christopher Begg, Co-Founder, East Coast Asset Management Gilchrist Berg, Founder, Water Street Capital C.T. Fitzpatrick, Founder, Vulcan Value Partners Mark Holowesko, Founder, Holowesko Partners Bernard Horn Jr. Founder, Polaris Capital Management Bill Kanko, Founder, Black Creek Investment Management William Priest, Co-Founder, Epoch Investment Partners Robert Rohn, Founder, Sustainable Growth Advisers Lewis Sanders, Founder, Sanders Capital Dr John -

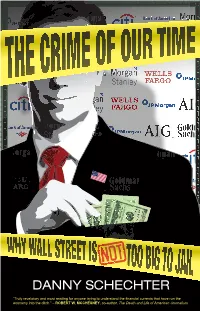

The Crime of Our Time, Is a Hard-Hitting Investigation That Shows How the fi Nancial Crisis Was Built on a Foundation of Criminal Activity

SCHECHTER “Fully living up to his reputation as the ‘News Dissector,’ Danny Schechter goes right for the jugular DANNY in this rich and informative analysis of the fi nancial crisis and its roots. Not errors, accident, market NOAM CHOMSKY uncertainty and so on, but crime: major and serious crime. A harsh judgment, but it is not easy to dismiss the case he constructs.” – “There are many forms of terrorism. And this economic terrorism, as Schechter writes, is perhaps even more dangerous to the nation than the attacks of 9/11.” – CHRIS HEDGES, author of Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle In 2006, fi lmmaker Danny Schechter was denounced as an “alarmist” for his fi lm In Debt We Trust, which warned of the coming credit crisis. He was labeled a “doom and gloomer” until the economy melted down, vin- dicating his warnings. His prescient new book, The Crime Of Our Time, is a hard-hitting investigation that shows how the fi nancial crisis was built on a foundation of criminal activity. To tell this story, Schechter speaks with bankers involved in these activi- ties, respected economists, insider experts, top journalists including Paul Krugman, and even a convicted white-collar criminal, Sam Antar, who blows the whistle on these intentionally dishonest practices. The Crime Of Our Time looks into how the crisis developed, from the mysterious collapse of Bear Stearns to the self-described “shitty deals” of Goldman Sachs. Schechter calls for a full criminal investigation and structural reforms of fi nancial institutions to insure accountability by the white-collar perpetrators who profi ted from the misery of their victims. -

Private Sector Advisory Group

Private Sector Advisory Group Peter Dey is the current chairman of PSAG. He is also the chairman of Paradigm Capital Inc., Canada, and chairman and/or independent director of a number of companies listed in Toronto, New York, and London, including Redcorp Ventures Ltd., Goldcorp Inc., Sun-Times Media Group Inc., and Alpine Canada. In 2010, he received the Lifetime Achiever Award from the International Corporate Governance Network for his work globally on corporate governance. More recently, he was a partner in Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt, specializing in corporate board issues and mergers and acquisitions. Prior to that role, he was chairman of Morgan Stanley Canada Limited. Dey chaired the Toronto Stock Exchange Committee on Corporate Governance in Canada, which released, in December 1994, a report titled "Where Were the Directors?" also known as the "Dey Report." Dey was Canada's representative to the OECD Task Force, which developed the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance and is vice chairman of a Business Sector Group established by the OECD in April of 2005 to give practical guidance to board members seeking to adopt the OECD Principles. Christian Strenger is deputy chair of PSAG. He is a member of the German Government Commission on Corporate Governance and the Capital Markets Committee/German Ministry of Finance, as well as director of the Center for Corporate Governance at the HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management. Furthermore, he is a Chairman or member of several supervisory boards [DWS Investment GmbH (Frankfurt), a leading international mutual fund manager; Evonik Industries AG (Essen), Fraport AG (Frankfurt), The Germany Funds (New York/Chairman), and TUI AG (Hannover)]. -

Mobius on Emerging Markets: to Educate Global Investors About Closed-End Funds

Vol. IX, No. 1 A Global View of the Closed-End Fund Industry January 2009 THE SCOTT LETTER is intended Mobius on Emerging Markets: to educate global investors about closed-end funds. Closed-end Emerging Markets Expected to Grow Faster than the funds can be a valuable and profitable investment tool. To Developed Markets learn about closed-end funds, visit our web site, Once U.S. Recovers, Global Growth Will Continue www.CEFAdvisors.com, and in particular, read our article, What e interviewed Dr. Mobius by telephone economies in Asia are becoming more Are Closed-End Funds. Feel free Win Australia on December 30, 2008: domestically driven. Indeed, the services to forward this newsletter to SL: Good morning, Mark! What are you sector is gaining importance, especially in anyone who you believe could doing in Australia? China and India. Combined with govern- benefit from information on closed-end funds or Mobius: Well, it’s New Year’s eve and I ment expenditure in areas such as infra- global portfolios. am just relaxing, catching up on my reading structure as well as private and domestic here in Queensland. It’s beautiful here. consumption, this means the emerging – George Cole Scott Editor-in-Chief SL: That’s a beautiful climate this time of economies should be able to offset, at least year. Sounds like you are still in good health at partially, any decline in growth resulting 72, despite this difficult year. You still have no from slowing exports with an increased plans to retire, right? economic independence. The accumula- Mobius: That’s right. -

Dr Mark Mobius Emerging Markets Economist Former Executive Chairman, Franklin Templeton

Feb 20 Dr Mark Mobius Emerging Markets Economist Former Executive Chairman, Franklin Templeton Global Emerging Markets and Investment Strategies Regarded by many in the financial industry as one of the most successful emerging markets investors over the last 25 years. Professional experience • A celebrated veteran in global emerging markets, Dr Mobius has spent over 40 years working in and traveling throughout emerging and frontier markets. He was executive chairman of Templeton Emerging Markets Group, where he established and directed the research team based in 18 global emerging markets offices and managed more than $50 billion in emerging markets portfolios. • During his tenure the Templeton Emerging Markets Group expanded assets under management from US$100 million to over US$ 40,000 million, and launched a number of emerging market and frontier funds focusing on Asia, Latin America, Africa and Eastern Europe. • Prior to joining Templeton Dr. Mobius was Chief Executive of International Investment Trust. • Dr. Mobius has been a key figure in developing international policy for emerging markets. In 1999, he was selected to serve on the World Bank’s Global Corporate Governance Forum as a member of the Private Sector Advisory Group and as co-chairman of its Investor Responsibility Task Force. • He is a current member of the Economic Advisory Board of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and has been a supervisory board member of OMV Petrom in Romania since 2010. Previously, he served as a Director on the Board of Lukoil, the Russian oil company. • Mark Mobius has received numerous industry awards numerous industry awards, most recently including the Life Time Achievement Award in Asset Management (2017) Global Investor Magazine; 50 Most Influential People (2011) Bloomberg Markets Magazine; Africa Investor Index Series Awards (2010) African Investor; and the Top 100 Most Powerful and Influential People (2006) Asiamoney.