Behind the Veneer: South Shoreditch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preventing the Displacement of Small Businesses Through Commercial Gentrification: Are Affordable Workspace Policies the Solution?

Planning Practice & Research ISSN: 0269-7459 (Print) 1360-0583 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cppr20 Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: are affordable workspace policies the solution? Jessica Ferm To cite this article: Jessica Ferm (2016) Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: are affordable workspace policies the solution?, Planning Practice & Research, 31:4, 402-419 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2016.1198546 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 30 Jun 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 37 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cppr20 Download by: [University of London] Date: 06 July 2016, At: 01:38 PLANNING PRACTICE & RESEARCH, 2016 VOL. 31, NO. 4, 402–419 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2016.1198546 OPEN ACCESS Preventing the displacement of small businesses through commercial gentrification: are affordable workspace policies the solution? Jessica Ferm Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The displacement of small businesses in cities with rising land values Gentrification; displacement; is of increasing concern to local communities and reflected in the affordable workspace; urban literature on commercial or industrial gentrification. This article policy; small businesses explores the perception of such gentrification as both a problem and an opportunity, and considers the motivations and implications of state intervention in London, where policies requiring affordable workspace to be delivered within mixed use developments have been introduced. -

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Igniting Change and Building on the Spirit of Dalston As One of the Most Fashionable Postcodes in London. Stunning New A1, A3

Stunning new A1, A3 & A4 units to let 625sq.ft. - 8,000sq.ft. Igniting change and building on the spirit of Dalston as one of the most fashionable postcodes in london. Dalston is transforming and igniting change Widely regarded as one of the most fashionable postcodes in Britain, Dalston is an area identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. It is located directly north of Shoreditch and Haggerston, with Hackney Central North located approximately 1 mile to the east. The area has benefited over recent years from the arrival a young and affluent residential population, which joins an already diverse local catchment. , 15Sq.ft of A1, A3000+ & A4 commercial units Located in the heart of Dalston and along the prime retail pitch of Kingsland High Street is this exciting mixed use development, comprising over 15,000 sq ft of C O retail and leisure space at ground floor level across two sites. N N E C T There are excellent public transport links with Dalston Kingsland and Dalston Junction Overground stations in close F A proximity together with numerous bus routes. S H O I N A B L E Dalston has benefitted from considerable investment Stoke Newington in recent years. Additional Brighton regeneration projects taking Road Hackney Downs place in the immediate Highbury vicinity include the newly Dalston Hackney Central Stoke Newington Road Newington Stoke completed Dalston Square Belgrade 2 residential scheme (Barratt Road Haggerston London fields Homes) which comprises over 550 new homes, a new Barrett’s Grove 8 Regents Canal community Library and W O R Hoxton 3 9 10 commercial and retail units. -

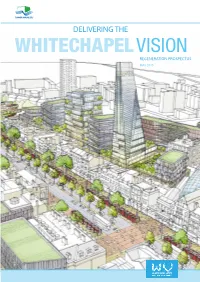

Whitechapel Vision

DELIVERING THE REGENERATION PROSPECTUS MAY 2015 2 delivering the WHitechapel vision n 2014 the Council launched the national award-winning Whitechapel Masterplan, to create a new and ambitious vision for Whitechapel which would Ienable the area, and the borough as a whole, to capitalise on regeneration opportunities over the next 15 years. These include the civic redevelopment of the Old Royal London Hospital, the opening of the new Crossrail station in 2018, delivery of new homes, and the emerging new Life Science campus at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). These opportunities will build on the already thriving and diverse local community and local commercial centre focused on the market and small businesses, as well as the existing high quality services in the area, including the award winning Idea Store, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the East London Mosque. The creation and delivery of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan has galvanised a huge amount of support and excitement from a diverse range of stakeholders, including local residents and businesses, our strategic partners the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, and local public sector partners in Barts NHS Trust and QMUL as well as the wider private sector. There is already rapid development activity in the Whitechapel area, with a large number of key opportunity sites moving forward and investment in the area ever increasing. The key objectives of the regeneration of the area include: • Delivering over 3,500 new homes by 2025, including substantial numbers of local family and affordable homes; • Generating some 5,000 new jobs; • Transforming Whitechapel Road into a destination shopping area for London • Creating 7 new public squares and open spaces. -

EC1 Local History Trail EC1 Local Library & Cultural Services 15786 Cover/Pages 1-4 12/8/03 12:18 Pm Page 2

15786 cover/pages 1-4 12/8/03 12:18 pm Page 1 Local History Centre Finsbury Library 245 St. John Street London EC1V 4NB Appointments & enquiries (020) 7527 7988 [email protected] www.islington.gov.uk Closest Tube: Angel EC1 Local History Trail Library & Cultural Services 15786 cover/pages 1-4 12/8/03 12:18 pm Page 2 On leaving Finsbury Library, turn right down St. John Street. This is an ancient highway, originally Walk up Turnmill Street, noting the open railway line on the left: imagine what an enormous leading from Smithfield to Barnet and the North. It was used by drovers to send their animals to the excavation this must have been! (Our print will give you some idea) Cross over Clerkenwell Rd into market. Cross Skinner Street. (William Godwin, the early 18th century radical philosopher and partner Farringdon Lane. Ahead, you’ll see ‘Well Court’. Look through the windows and there is the Clerk’s of Mary Wollestonecraft, lived in the street) Well and some information boards. Double back and turn into Clerkenwell Green. On your r. is the Sessions House (1779). The front is decorated with friezes by Nollekens, showing Justice & Mercy. Bear right off St John Street into Sekforde Street. Suddenly you enter a quieter atmosphere...On the It’s now a Masonic Hall. In the 17th century, the Green was affluent, but by the 19th, as Clerkenwell was right hand side (rhs) is the Finsbury Savings Bank, established at another site in 1816. Walk on past heavily industrialised and very densely populated with poor workers, it became a centre of social & the Sekforde Arms (or go in if you fancy!) and turn left into Woodbridge Street. -

2,398 Sq Ft (223 M ) Arch 329 Stean Street Haggerston London E8

Arch 329 Stean Street Haggerston London E8 4ED . TO LET - Arch with a secure yard 2,398 sq ft (223 m2) B1 /B2/B8 Opportunity *or alternative uses STPP* Location Terms The subject property is located in prominent position to the A new full repairing and insuring lease is available for a term north east of the city and can be accessed from Stean Street and by agreement, at a rent of £60,000 per annum, plus VAT. Acton Mews. The A10 is a short distance to the west of the Subject to Contract. property and provides a direct route to the M25. The area is well served by public transport with a number of bus routes Description passing close to the premises, most notably from the A10 The property comprises of an unlined arch which can be Kingsland Road. Haggerston station (London Overground) is accessed from Stean Street or Acton Mews. The access on each located within 4 minutes walk of the property and provides elevation is via a manual sliding shutter door with a width of direct access into the city. 4.5m and height of 3.42m. Internally, the arch is in a Floor Areas (approx) GIA reasonable condition and benefits from:- Floor Areas GIA (approx): 2 Arch 329 Sq ft (m ) Strip Lighting Arch 2,398 223 3 Phase electricity Yard 1,059 98 Male/Female WC’s Total 3,457 321 Alarm System & CCTV 2 Gas fired blow heaters (unconnected) Legal Costs Rates We understand from the London Borough of Hackney that the Parking available on either side of the arch. -

Retail & Leisure Opportunities for Lease

A NEW VIBRANT COMMERCIAL AND RESIDENTIAL HUB IN SHOREDITCH Retail & Leisure Opportunities For Lease SHOREDITCH EXCHANGE, HACKNEY ROAD, LONDON E2 LOCATION One of London’s most creatively dynamic and WALKING TIMES culturally vibrant boroughs, Shoreditch is the 2 MINS Hoxton ultimate destination for modern city living. Within 11 MINS Shoreditch High Street walking distance of the City, the area is also 13 MINS Old Street superbly connected to the rest of London and beyond. 17 MINS Liverpool Street The development is situated on the north side of LONDON UNDERGROUND Hackney Road close to the junction of Diss Street from Old Street and Cremer Street. 3 MINS Bank 5 MINS King’s Cross St Pancras The immediate area boasts many popular 5 MINS London Bridge restaurants, gyms, independent shops, bars and 11 MINS Farringdon cafes including; The Blues Kitchen, Looking Glass 14 MINS Oxford Circus Cocktail Club, The Bike Shed Motorcycle Club. 18 MINS Victoria The famous Columbia Road Flower Market is just 19 MINS Bond Street a 3 minute walk away and it’s only a 5 minute walk to the heart of Shoreditch where there’s Boxpark, Dishoom and countless more bars, shops and LONDON OVERGROUND restaurants. from Hoxton 10 MINS Highbury & Islington Bordering London’s City district, local transport 12 MINS Canada Water links are very strong with easy access to all the 14 MINS Surrey Quays major hubs of the West End and City. Numerous 29 MINS Hampstead Heath bus routes pass along Hackney Road itself which Source: Google maps and TFL also provides excellent links. Hoxton Overground station is just a 2 minute walk away. -

Controlled Parking Zones

l ISLINGTON Controlled Parking Zones Version 29 0 0.5 1 Kilometers Note: This map is designed as a guide only and should not be used as a definitive layout of CPZs within Islington Borough Boundary Match Day Area Boundary Red Route Parking Restrictions A- Zone A Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm B - Zone B Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm C - Zone C Monday to Saturday At Any Time, Sunday Midnight -6am D - Holloway West Mon - Fri 9.30am - 4.30pm E - Zone E Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 4.30pm Sun & Public Hols Noon - 4.30pm F - Nags Head Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 4.30pm Sun & Public Hols Noon - 4.30pm G - Gillespie Mon - Fri 1Oam - 2pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 2pm - 8.30pm Sat, Sun & Public Hols Noon - 4.30pm H - Finsbury Park Mon - Sat 8.30am - 6.30pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 6.30pm Sun & Public Hols Noon - 4.30pm HE - Hillrise East Mon - Fri 1 Oam - 2pm J - Finsbury Park Mon - Sat 8.30am - 6.30pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 6.30pm Sun & Public Hols Noon - 4.30pm K - Whittington At any time L - Canonbury S - Thornhill Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 4.30pm T - East Canonbury Sun & Public Hols Noon - 4.30pm Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm N - Barnsbury North TW - Tollington West Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm Mon - Fri 1Oam - 2pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 4.30pm U - Junction South Sun & Public Hols Noon - 4.30pm Mon - Fri 1Oam - Noon P -Archway V- Mildmay Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 1.30pm Matchday Controls: Q - Quadrant Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm, Sat 8.30am - 4.30pm Mon - Fri 8.30am - 6.30pm Sun & Public Hals Noon - 4.30pm Matchday Controls: Mon - Fri 8.30am - 8.30pm W - St. -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

In-The-East, Limehouse, Bermondsey, and Lee

1006 VITAL STATISTICS OF LONDON DURING SEPTEMBER, 1897. scarlet fever, and not one either from small-pox, measles, among the various sanitary areas in which the diphtheria, or whooping-cough. These 17 deaths were equal to patients had previously resided. During the five weeks an annual rate of 2 5 per 1000, the zymotic death-rate during ending Saturday, October 2nd, the deaths of 6687 persona the same period being 2’0 in London and 1-8 in Edin- belonging to London were registered, equal to an annual’ burgh. The fatal cases of diarrhoea, which had been 21 rate of 15-6 per 1000, against 13-9, 183, and. 23 in and 8 in the two preceding weeks, rose again to 10 last the three preceding months. The lowest death-rates week. The deaths referred to different forms of "fever," during September in the various sanitary areas were whichhad been 6,9, and 6 in the three preceding weeks, further 10’7 in Hampstead, 11’2 in Wandsworth, 11’5 in declined to 4 last week. The mortality from measles slightly St. James Westminster, 11’6 in Stoke Newington, 119’ exceeded that recorded in the preceding week. The 147 in St. George Hanover-square and in Lewisham (ex. deaths in Dublin last week included 34 of infants under cluding Penge), 12-5 in Kensington, and 12-8 in Lee; the one year of age and 39 of persons aged upwards of sixty highest rates were 20-4 in St. George Southwark, 21 in years; the deaths of both infants and of elderly persons St. -

First Notice. First Notice. First Notice, First Notice.

Adjournment thereof, which sliall happen next after Thomas Rogers, formerly of Tleet-market, in the Parish of St* THIRTY Bride, London, late of St. John-street Clerkenwell, in the Days from the FIRST Publication - County of Middlesex, Glocer. 'of the under-mentioned Names, viz. Thomas Snead, formerly of the Parish of St. Peter, in the City of Hereford, Joiner and Cabinet-rriaker> late of die Pa ' Prisoners in the KING's BENCH Rrifon-, rish of St, George, in the Borough of Southwark, Victualler. in the County of Surry. John Smith, late of -St. George's Hanover-square, in the County of Middlesex, Taylor and Victualler.' First Notice. Matthew Thompson, late of Snow's Fields,"" in tie Parilh of St. Mary Magdalen Bermondsey, in the County of Surry William Henry Shute, late of Cornhill, London,_ Sword Ca'rpenter and Shopkeeper. Cutler and Hatter. # . Ludovicus Hislop, late of Cambridge-street in the Parish of St. Henry Rivers, formerly of Worcester, late of Liverpool, in James, in the County cf Middlesex, Gentleman. thc County of Lancaster, Yeoman. Joseph Dand, late of Piccadilly in the Parish of St. James in Thames Andrews, late of Wych-street, in the Parish of St. the County of Middlesex, Stocking-maker and Hosier. St. Clement Danes, Hat-maker. William Knight, kte of Guildsord- in the County of Surry, Francis lic.ll, late of the Parish ofRedburn, in the County Butcher. os Hertford, Innholder. Samuel Monk, formerly of Comb-mill, in the Parish of Ilford, William Chilton, late of Great Windmill-street, in the Pa ' late.of Milton-hill-farm,-in.the Pariih of Milton, both in rish of St. -

Studying Craft: Trends in Craft Education and Training Participation in Contemporary Craft Education and Training

Studying craft: trends in craft education and training Participation in contemporary craft education and training Cover Photography Credits: Clockwise from the top: Glassmaker Michael Ruh in his studio, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian Head of Art Andrew Pearson teaches pupils at Christ the King Catholic Maths and Computing College, Preston Cluster, Firing Up, Year One. © University of Central Lancashire. Silversmith Ndidi Ekubia in her studio at Cockpit Arts, London, December 2013 © Sophie Mutevelian ii ii Participation in contemporary craft education and training Contents 1. GLOSSARY 3 2. FOREWORD 4 3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 3.1 INTRODUCTION 5 3.2 THE OFFER AND TAKE-UP 5 3.3 GENDER 10 3.4 KEY ISSUES 10 3.5 NEXT STEPS 11 4. INTRODUCTION 12 4.1 SCOPE 13 4.2 DEFINITIONS 13 4.3 APPROACH 14 5. POLICY TIMELINE 16 6. CRAFT EDUCATION AND TRAINING: PROVISION AND PARTICIPATION 17 6.1 14–16 YEARS: KEY STAGE 4 17 6.2 16–18 YEARS: KEY STAGE 5 / FE 22 6.3 ADULTS: GENERAL FE 30 6.4 ADULTS: EMPLOYER-RELATED FE 35 6.5 APPRENTICESHIPS 37 6.6 HIGHER EDUCATION 39 6.7 COMMUNITY LEARNING 52 7. CONCLUDING REMARKS 56 8. APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY 57 9. NOTES 61 1 Participation in contemporary craft education and training The Crafts Council is the national development agency for contemporary craft. Our goal is to make the UK the best place to make, see, collect and learn about contemporary craft. www.craftscouncil.org.uk TBR is an economic development and research consultancy with niche skills in understanding the dynamics of local, regional and national economies, sectors, clusters and markets.