Cantonese Students' Perspectives on the Use of Their First Language in Acquiring English EXAMINING COMMITTEE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Reading Strategies Used by Chinese Efl Learners

ACADEMIC READING STRATEGIES USED BY CHINESE EFL LEARNERS: FIVE CASE STUDIES by LI CHENG B.A. Beijing Normal University, 1990 M.A. Beijing Normal University, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Language and Literacy Education) We accept this thesis as confirming to Jhe required ^tandard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 2003 © Li Cheng, 2003 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date A]>r%*£} DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT The number of people learning English as a second or foreign language has increased dramatically over the last two decades. Many of these second language learners are university students who must attain very sophisticated academic skills. To a great extent, their academic success hinges on their ability to read a second language. This multiple- case study investigated first language (LI) and second language (L2) reading strategies in academic settings. The study drew on Bernhardt's (2000) socio-cognitive model of second language reading. Five Chinese students in a graduate program in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) volunteered to participate in the study. -

Tilburg University Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Lu, Y

Tilburg University Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Lu, Y. Publication date: 2020 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Lu, Y. (2020). Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media: Practices, products, communities and markets in a knowledge economy . [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. okt. 2021 Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Practices, products, communities and markets in a knowledge economy Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Practices, products, communities and markets in a knowledge economy PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. K. Sijtsma, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Aula van de Universiteit op woensdag 19 augustus 2020 om 16.30 uur door LU Ying geboren te Hebei, China Promotores: prof. -

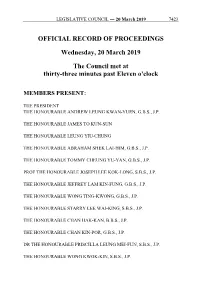

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 20 March 2019 7423 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 20 March 2019 The Council met at thirty-three minutes past Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. 7424 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 20 March 2019 THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CLAUDIA MO THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL TIEN PUK-SUN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WU CHI-WAI, M.H. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN CHI-CHUEN THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG CHE-CHEUNG, S.B.S., M.H., J.P. -

First Language Maintenance: the Comparison of Chinese Immigrant Parents'

First Language Maintenance: The Comparison of Chinese immigrant parents' attitudes, the children's language use patterns and their family environments by Huei-tzu Tsai B. A., Taipei Municipal Teachers College, Taiwan, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF . CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August, 1997 ©Huei-tzu Tsai, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2788) Abstract An exploratory study was conducted to investigate Chinese parents' attitudes toward their children's first language maintenance. Interviews were conducted to collect data from a total of 30 parents who came from two distinct socioeconomic and educational backgrounds. Fifteen parents sent their children to a university lab preschool (ULP group) and the other fifteen enrolled their children in a community-based day care (CDC group) in a Chinese-speaking neighborhood in Vancouver. The Family Environment Scale (FES) (Moos, 1974) was also used to collect information about the family social and emotional dynamics. -

Tilburg University Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Lu, Y

Tilburg University Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Lu, Y. Publication date: 2020 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Lu, Y. (2020). Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media: Practices, products, communities and markets in a knowledge economy . [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. okt. 2021 Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Practices, products, communities and markets in a knowledge economy Biaoqing on Chinese Social Media Practices, products, communities and markets in a knowledge economy PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. K. Sijtsma, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Aula van de Universiteit op woensdag 19 augustus 2020 om 16.30 uur door LU Ying geboren te Hebei, China Promotores: prof. -

Christian Music As a Contact Zone for Chinese and Hong Kong Communities in Post-Colonial Hong Kong

CHRISTIAN MUSIC AS A CONTACT ZONE FOR CHINESE AND HONG KONG COMMUNITIES IN POST-COLONIAL HONG KONG A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Yan Xian October 20, 2014 Thesis written by Yan Xian B.A., Nanjing Arts Institute, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2014 Approved by Andrew Shahriari, Ph.D., Advisor Ralph Lorenz, Ph.D., Acting Director, School of Music John Crawford, Ed.D., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENT ........................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ................................................................................................................................. 1 I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 Orientation to Hong Kong ..................................................................................................... 2 Review of Related Literature ................................................................................................