Divine Knowledge at Harvard and Yale: from William Ames to Jonathan Edwards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

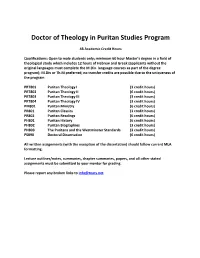

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching. -

Preparation for Grace in Puritanism: an Evaluation from the Perspective of Reformed Anthropology

Diligentia: Journal of Theology and Christian Education E-ISSN: 2686-3707 ojs.uph.edu/index.php/DIL Preparation for Grace in Puritanism: An Evaluation from the Perspective of Reformed Anthropology Hendra Thamrindinata Faculty of Liberal Arts, Universitas Pelita Harapan [email protected] Abstract The Puritans’ doctrine on the preparation for grace, whose substance was an effort to find and to ascertain the true marks of conversion in a Christian through several preparatory steps which began with conviction or awakening, proceeded to humiliation caused by a sense of terror of God’s condemnation, and finally arrived into regeneration, introduced in the writings of such first Puritans as William Perkins (1558-1602) and William Ames (1576-1633), has much been debated by scholars. It was accused as teaching salvation by works, a denial of faith and assurance, and a divergence from Reformed teaching of human's total depravity. This paper, on the other hand, suggesting anthropology as theological presupposition behind this Puritan’s preparatory doctrine, through a historical-theological analysis and elaboration of the post-fall anthropology of Calvin as the most influential theologian in England during Elizabethan era will argue that this doctrine was fit well within Reformed system of believe. Keywords: Puritan, Reformed Theology, William Perkins, William Ames, England, Grace. Introduction In his book on Jonathan Edwards’s biography, Marsden tells a story about Edwards’s struggle with a question related to his spirituality, whether -

William B. Hunter Argues

SEL 32 (1992) ISSN 0039-3657 The Provenance of the Christian Doctrine WILLIAM B. HUNTER The year 1991 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Maurice Kelley's This Great Argument with the subtitle A Study of Milton's "De Doctrina Christiana" as a Gloss upon "Paradise Lost".' One can make a good case that it has been the most influential work of Milton scholarship published in this century; on this an- niversary it is appropriate to review its successes and failures, and especially its fruitful thesis that the theological treatise provides a major interpretative gloss for the poem, as its subtitle states. Such a fertile theory has given inspiration to others who have applied it to the rest of Milton's poetry and prose, especially the later works. It is safe to say that lacking the thesis of This Great Argument, Bright Essence would not exist and Milton's Brief Epic, Toward Samson Agonistes, and Milton and the English Revolution would be quite different books from the ones we know.2 Significant too is the fact that Kelley saw no cause to change his arguments radically during the rest of his productive career. He was the obvious choice to edit the Christian Doctrine for the sixth volume of the Yale Prose. Its extensive introduction is to a considerable extent a recapitulation and occasional expansion of the work printed over thirty years earlier. Indeed, as Kelley himself observes, he sometimes repeated the earlier argument word for word in the introduction to the edition.3 In view of the heterodoxy of much of the Christian Doctrine, Milton is now interpreted in many of his works, not just in the treatise, as a heretic-the opposite from the views that almost William B. -

Increase Mather^S 'Catechismus Logkus^: a Translation and an Analysis of the Role of a Ramist Catechism at Harvard

Increase Mather^s 'Catechismus Logkus^: A Translation and an Analysis of the Role of a Ramist Catechism at Harvard RICK KENNEDY and THOMAS KNOLES N 1661 a Harvard freshman opened a letter from his uncle and received the following advice on how best to pursue his Istudies in college: above all he should learn 'the method of the incomparable P. Ramus as to every art he hath wrot upon. Get his definitions and distributions into your mind and memory.'' Yet, as Leonard Hoar urged his nephew Josiah Flynt to appreciate the importance of the logic system of Peter Ramus (Pierre de la Ramée, 1515?-! 572), Ramism was nearing the end of its hundred- year term of popularity. Nonetheless, the doctrines of Ramism would play a role in Increase Mather's plans for Harvard's regen- eration after Hoar's own troubled tenure as president of the col- lege had brought the institution close to extinction. Thus, as ad- vice for Harvard students. Hoar's prescriptions would continue to have merit for some years to come. Despite the fact that Ramist doctrines were already on the de- cline, in 1675 Increase Mather produced a brief manuscript logic catechism in Latin for the use of Harvard College undergradu- ates. The title in the most complete surviving copy is Catechismus i.LeonardHoar to Josiah Flynt, March 27, i66i,in Samuel ¥.. Monsoo, Harvard Col- lege in the Seventeenth Century, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936), 2:640. RICK KENNEDY is professor of history at Point Loma Nazarene University and THOMAS KNOLES IS curator of manuscripts at the American Andquarian Society. -

John Cotton: the Antinomian Calvinist

JOHN COTTON: THE ANTINOMIAN CALVINIST By Gregory Allen Selmon Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion May, 2008 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor James P. Byrd Professor James Hudnut-Beumler Professor Paul Dehart Professor John S. McClure Professor Joel Harrington To my supportive and loving family: this dissertation is a testimony to God’s grace and your support ii ACKOWLEDGEMENTS This work illustrates the faithful love and support I have received from my family. While they often doubted the system, they never wavered in their support of me. I would like to thank my loving wife, Mary Elizabeth, for seeing me through this project. She had many days of being a graduate student widow. I also would like to thank my children- Preston, Geneva, Elijah, and Isaac- who have grown up knowing nothing but Dad working on some crazy dissertation project. I constantly try to teach them that perseverance is the most important trait in life. This work is an illustration of perseverance and not my brilliance! I also would like to thank Dr. James Byrd for his advice and assistance with this project. His comments, particularly in the end of this process, were extremely helpful in clarifying and focusing my argument. Finally, I also want to thank President Terry Phillips of Grace Evangelical College and Seminary in Bangor, Maine for his support and proof-reading expertise. His comments and assistance only made this project better. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION............................................................................................................. -

Reconsidering Arminius

Arminius: a grand divide in theology Reconsidering Arminius The theology of Dutch theologian Jacob Arminius has been misinterpreted and carica- tured in both Reformed and Wesleyan circles. But by revisiting Arminius’s theology, this book hopes to be a constructive voice in the discourse between so-called Calvinists and Arminians. Traditionally, Arminius has been treated as a divisive figure in evangelical theology. In- deed, one might be able to describe classic evangelical theology up into the twentieth century in relation to his work: one was either an Arminian and accepted his theology, or one was a Calvinist and rejected his theology. Although various other movements within evangelicalism have provided additional contour to the movement (fundamentalism, Pentecostalism, and so on), the Calvinist-Arminian “divide” remains a significant one. What this book seeks to correct is the misinterpretation of Arminius as one whose theol- Reconsidering ogy provides a stark contrast to the Reformed tradition as a whole. Indeed, this book will demonstrate instead that Arminius is far more in line with Reformed orthodoxy than popularly believed and will show that what emerges as Arminianism in the theology of Arminius the Remonstrants and Wesleyan movements was in fact not the theology of Arminius but a development of and sometimes departure from it. This book also brings Arminius into conversation with modern theology. To this end, it includes essays on the relationship between Arminius’s theology and open theism and Neo-Reformed theology. In this way, this book fulfills the promise of the title by showing ways in which Arminius’s theology— once properly understood—can serve as a resource for evangelical Wesleyans and Calvinists doing theology together today. -

BOOK REVIEWS 759 Anglo-Americans Adopted the “Skulking Way of War” Involves Neither Religion Nor Gender but the Introduction

BOOK REVIEWS 759 Anglo-Americans adopted the “skulking way of war” involves neither religion nor gender but the introduction of European military hard- ware’s killing capacity. Moreover, Romero fails to acknowledge that the dynamics of cultural change did not affect the two parties equally: New Englanders may have added Native maneuvers to their tactical repertoire, but they did not adapt Algonquian technologies en masse, inflect Reformed Protestantism with Native theology, or alter their inherited conceptions of masculinity, while for their part—though traditionalists resisted English religious and gender norms—Indians more readily embraced elements of European technology, and a few did convert. The insights of Romero’s gender analysis do not alter the trajectory of Indian–New English relationships. By 1700, southern New England’s tribes faced a range of choices rendered “increasingly narrow” more by Anglo-American society’s expanding demographic, economic, and technological resources than by its “particular vision of colonial and Christian manliness” (p. 197). Charles L. Cohen is Professor of History and Religious Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Founding Director of the Lubar Institute for the Study of the Abrahamic Religions. Godly Republicanism: Puritans, Pilgrims, and a City on a Hill.By Michael P. Winship. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012. Pp. 340.$49.95.) “Whig history” has long since fallen into disfavor among histori- ans, and few academics today would be willing to laud the New England meetinghouse as a laboratory for American democracy. But, as Michael Winship argues in this deeply researched book, “historiographical excesses” should not be held against the puritans (p. -

Herman Bavinck's Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae

BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. What’s next? What is there for me to do?”1 There was, in fact, a lot to do. The young candidate for the ministry received two calls from Christian Reformed churches: Franeker and Broek op Langedijk. Bavinck accepted the call to Franeker. During his pastorate in this Frisian congregation, he edited the sixth edition of the Leiden Synopsis of Purer Theology (1625). This textbook in systematic theology, consisting of 52 disputations, was composed between 1620–1624 by four professors of theology: Johannes Polyander, Andreas Rivetus, Antonius Walaeus, and * Henk van den Belt has introduced Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. Mathilde de Vries-van Uden has provided the English trans- lation of the Latin text of Bavinck’s Preface. 1 “En zoo gaat alles voorbij en ligt heel de studententijd achter mij. En wat nu? Wat is er voor mij te doen?” Archive of Herman Bavinck, Historical Documentation Center for Dutch Protestantism (1800–today), Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, col- lection 346, number 16 “Dagboekjes,” entry on June 11, 1880. 101 HENK VAN DEN BELT AND MATHILDE DE VRIES-VAN UDEN Antonius Thysius. The collection was reprinted in 1632, 1642, 1652, and 1658.2 From the start of his pastorate in Franeker, Bavinck was engaged in the task of editing the sixth edition.