What It Is to Be a Métis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kelsey Cox @ Joussard, AB 1 LSWC 2016-17 Annual Report

Photo by: Kelsey Cox @ Joussard, AB 1 LSWC 2016-17 Annual Report Thank You to our 2016-17 Financial Supporters LSWC 2016-17 Annual Report 2 Table of Contents LSWC Financial Supporters Page 1 Table of Contents Page 2 Map of the Watershed Page 3 Message from the Chair Page 4 2016-17 Board of Directors Page 5 Summary of 2016 Operations Pages 6-8 LSWC 2016-17 financials Pages 9-12 Watershed Resiliency and Restoration Page 13 Watershed Wise Page 14 Out and About in the Watershed Page 15 Little Green Thumbs Page 16 Partners in Environmental Education Page 17 Around the Watershed Page 18 Sunset at Joussard, Ab. Photo by Traci Hansen 3 LSWC 2016-17 Annual Report The Lesser Slave Watershed The Lesser Slave Watershed is centered around Lesser Slave Lake. Water in our lake comes from several tributaries including the South Heart River, the East and West Prairie Rivers, the Driftpile River, and the Swan River. The Lesser Slave River is the only outlet of Lesser Slave Lake and it flows from the Town of Slave Lake to the Athabasca River about 75km East of Slave Lake. Sunset silhouettes at Spruce Point Park, AB. Photo by Danielle Denoncourt LSWC 2016-17 Annual Report 4 Message from the Chair When I first came on as a Board member I had no clue what environmental issues affected my area and what I could offer to the organization. I just knew I wanted to try and create a healthy environment for our youth to inherit and one our elders could enjoy and be proud of. -

Current Contact Information

Current Contact Information Tribal Chiefs Employment & North East Alberta Apprenticeship Xpressions Arts & Design Training Services Association Initiative West Phone: (780) 520-7780 17533--106 Avenue, Edmonton, AB 15 Nipewan Road, Lac La Biche, AB Phone: (780) 481-8585 Cell: (780) 520-7375 Fax: (780) 488-1367 Cell: (780) 520-7644 TCETSA - Small Urban Offce North East Alberta Apprenticeship St. Paul, AB Initiative East Phone: (780) 645-3363 6003 47 Ave, Bonnyville, AB Fax: (780) 645-3362 Cell: (780) 812-6672 TCETSA VISION STATEMENT To provide a collaborative forum for those committed to the success of First Nations people by exploring and creating opportunities for increased meaningful and sustainable workforce participation Beaver Lake Cree Nation Heart Lake First Nation Human Resource Offce Human Resource Offce Phone: (780) 623-4549 Phone: (780) 623-2130 Fax: (780) 623-4523 Fax: (780) 623-3505 Beaver Lake Daycare Heart Lake Daycare Phone: (780) 623-3110 Phone: (780) 623-2833 Fax: (780) 623-4569 Fax: (780) 623-3505 Cold Lake First Nations Kehewin Cree Nation Human Resource Offce Human Resource Offce Phone: (780) 594-7183 Ext. 230 Phone: (780) 826-7853 Fax: (780) 594-3577 Fax: (780) 826-2355 Yagole Daycare Kehew Awasis Daycare Phone: (780) 594-1536 Phone: (780) 826-1790 Fax (780) 594-1537 Fax: (780) 826-6984 Frog Lake First Nation Whitefsh Lake First Nation #128 Human Resource Offce Human Resource Offce Phone: (780) 943-3737 Phone: (780) 636-7000 Fax: (780) 943-3966 Fax: (780) 636-3534 Lily Pad Daycare Whitefsh Daycare Phone: (780) 943-3300 Phone: (780) 636-2662 Fax: (780) 943-2011 Fax: (780) 636-3871 2 TCETSA | 2016-2017 Annual Report Our TREATY Model The TREATY Model All of our programs are designed around the TREATY Model process for the purpose of focusing on solutions. -

Grouard Nativeness Stressed

©R., KA4- `FG , INSIDE THIS WEEK CULTURE AND EDUCATION in today's world, is the topic of articles sent in by Grant MacEwan students. See Pages 6 and 7. WHAT DO YOU THINK? is a survey for you to respond to. Windspeaker poses its first question. See Page 6. MAXINE NOEL is making her annual visit to Edmonton. Terry Lusty presents October 10, 1986 a brief profile of this very successful printmaker and painter. See Page 12. Slim win for Ronnenberg By Lesley Crossingham Delegates also elected insults, innuendoes and ranging from incompetence appeared on general or Philip Campiou as vice - accusations. to opportunism were band lists. SEEBE - An exuberant Doris Ronnenberg president for northern Bearing the brunt of brought forward but were This led to another long announced she felt fully vindicated after her Alberta, Ray Desjardin for these accusations were ruled out of order by the and bitter debate, with one re- election as president of the Native central Alberta and Teresa Research Director Richard meeting chairman, NCC delegate, former treasurer Bone for southern Alberta. Long. Long was in residence national president Smokey and founder for Madge McRee, Council of Canada (Alberta) another Again, the vote total was at the ranch but did not Bruyere. who had her membership two term. -year not released to Wind - attend the meeting. Then another heated withdrawn, complaining The election came at the end of a grueling speaker. Tempers flared as several debate over membership that she was no longer day of heated debate at the NCC(A) annual Elected board members delegates accused Doris ensued after it was represented by any Indian assembly held at the luxurious Rafter 6 are: Leo Tanghe and Ronnenberg of nepotism discovered that several organization as the Indian Gordon Shaw for the by employing her - delegates, some of guest ranch at Seebe, overlooking the common whom Association of Alberta north, Gerald White and law husband, Richard had travelled from as far (IAA) and her band, Slave Stoney Indian reserve west of Calgary Frank Logan for central Long. -

Preliminary Soil Survey of the Peace River-High Prairie-Sturgeon Lake

PROVINCE OF ALBERTA Research Council of Alberta. Report No. 31. University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta. SOIL SURVEY DIVISION Preliminary Soi1 Survey of The Peace River-High Prairie- Sturgeon Lake Area BY F. A. WYATT Department of Soils University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta (Report published by the University of Alberta at the request of Hon. Hugh W. Allen, Minister of Lands and Mines) 1935 Price 50 cents. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. , DR. R. C. WALLACE, Director of Research, Resedrch Cowuil of Alberta, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta. Sir:- 1 beg to submit a report entitled “Preliminary Soi1 Survey of the Peace River-High Prairie-Sturgeon Lake Area,” prepared in co- operation with Dr. J. L. Doughty, Dr. A. Leahey and Mr. A. D. Paul. A soi1 map in colors accompanies this report. This report is compiled from five adjacent surveys c,onducted between the years 1928 and 1931. It includes a11 of two and parts of the other three surveys. The area included in the report is about 108 miles square with McLennan as the approximate geographical tenter. Respectfully submitted, F. A. WYATT. Department of Soils, University of, Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, April 15th, 1935. .-; ‘- TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Description of area ...............................................................................................................................................1 Drainage ........................................................................................................................................................................2 Timber -

Lac La Biche County Recreation & Culture Directory

Lac La Biche County FCSS This directory was created as an information service for the residents of this community, and the organizations and agencies working within its boundaries. We thank everyone who cooperated in providing information for this resource. If you know of corrections or changes that would help this directory become more accurate, please call the Lac La Biche County FCSS office at 623-7979 or fill out the form included at the back of this directory and mail it to the address provided. EMERGENCY 911 FOR FIRE, AMBULANCE, MEDICAL & POLICE SERVICE Child Abuse Hotline: 1-800-387-5437 Crime Stoppers: 1-800-222-8477 Addiction Services/Gambling Help Line: 1-866-332-2322 Hospital: 780-623-4404 Kids Help Line: 1-800-668-6868 Mental Health Crisis Services: 1-877-303-2642 Poison Control Centre 1-800-332-1414 Victim Services 623-7770 Women’s Shelter 780-623-3100 Lac La Biche County Community Services Directory Page 2 of 83 Population: Lac La Biche County: 9123 Incorporation: Lakeland County and the Town of Lac La Biche amalgamated in August, 2007 Health Unit: Lac La Biche Community Health Services 780-623-4471 Health Centre: W. J. Cadzow Health Centre 9110 - 93rd Street, Lac La Biche, AB T0A 2C0 Phone: 780-623-4404 R.C.M.P.: Lac La Biche Detachment #11 Nipewan Road. Lac La Biche 780-623-4380 (emergency line) 780-623-4012 (Admin.-Info) Fire: Hylo - 911 Buffalo Lake: 780-689-2170, 689-4639 or 689-1470 (cell) Les Hanson - Fire Chief; Caslan: 780-689-3911; Kikino: 780-623-7868; Rich Lake 911 Ambulance: 911 - Lac La Biche & District Regional EMS Mayor: Omer Moghrabi 780-623-1747 Administrator: Shadia Amblie 623-6803 Provincial MLA: Shayne Saskiw (Lac La Biche - St.Paul Const.) Box 1577 Unit 2, 4329– 50 Avenue St. -

High Prairie

9 10 11 12 18 17 16 15 24 19 20 21 22 23 3 2 1 7 8 9 14 13 18 24 19 20 82-20-W5 6 5 10 11 17 16 15 21 22 23 4 3 12 7 8 14 13 18 24 19 20 2 1 6 9 10 11 17 16 15 21 5 4 12 7 14 13 18 82-19-W5 3 2 82-17-W5 8 9 17 16 34 1 6 10 11 15 14 35 5 12 13 18 36 4 7 8 82-13-W5 17 31 82-18-W5 3 2 82-16-W5 9 16 15 32 33 1 10 11 14 13 34 6 5 82-15-W5 12 7 18 17 35 36 4 8 9 16 31 3 82-14-W5 10 32 2 1 11 12 33 34 6 5 7 8 35 4 9 10 36 3 11 27 26 31 32 2 1 12 25 33 6 7 8 9 82-10-W5 30 34 5 4 10 29 35 36 3 11 28 27 31 2 1 82-12-W5 12 7 26 32 33 6 5 8 9 25 34 4 30 29 35 36 3 2 82-11-W5 28 31 1 6 27 26 32 33 5 4 22 25 30 34 35 3 2 23 29 36 1 6 24 28 31 32 5 19 27 26 33 4 3 20 21 25 34 35 2 1 22 30 29 36 31 6 5 23 24 28 32 4 81-20-W5 19 27 26 33 34 20 21 25 35 36 22 30 29 31 23 28 32 33 34 81-19-W5 24 27 26 35 15 19 25 36 14 13 20 21 30 31 32 18 22 29 28 33 34 17 81-18-W5 23 27 35 36 16 24 19 26 25 31 15 14 20 30 32 33 13 21 29 28 18 22 23 27 17 24 26 25 16 81-17-W5 19 30 M 15 20 29 i 14 21 28 n 13 22 27 k 10 18 23 26 R 25 i 11 17 24 v 12 16 81-16-W5 19 20 30 29 7 15 21 28 e 27 14 r 8 9 13 22 23 26 25 10WILLIAM 18 17 24 19 30 29 11 12 16 81-15-W5 20 28 7 15 14 21 22 MCKENZIE 8 13 23 24 UTIKOOMAK RENO 9 10 18 17 81-14-W5 19 11 16 20 21 I.R.#151K 12 7 15 22 23 LAKE 3 2 8 14 13 24 1 9 18 81-13-W5 19 20 6 10 17 16 21 22 I.R.#155B 5 11 12 15 23 4 3 7 8 14 13 24 19 2 9 18 81-12-W5 20 1 10 17 16 21 6 11 15 14 5 4 12 7 13 81-11-W5 3 8 9 18 17 81-10-W5 2 10 16 34 1 6 11 15 14 35 5 12 7 13 18 36 4 3 8 17 16 31 32 2 9 10 15 14 33 1 11 12 13 34 6 5 7 18 17 35 36 4 8 9 16 -

Lesser Slave Lake Health Advisory Council

Building a better health system with the voice of our community Where we are The Lesser Slave Lake Health Advisory Council serves High Prairie, Lesser Slave Lake and Wabasca and a number of rural and remote communities including Faust, Grouard, Joussard, Kinuso, Red Earth Creek, Peerless Lake and Trout Lake. Our geographic area covers a range of landscapes, industries, and demographics, as well as long-established communities. (see map page 2). Accomplishments • Supported the need for the new High Prairie Health Complex, bringing services closer to where people live. • Recommended the need for an EMS ambulance garage in Wabasca. • Advocated for increased transportation options for those in rural areas and worked with AHS leadership to bring forward these concerns (ongoing). • Partnered with AHS to host a Community Conversation in High Prairie. Stakeholders engaged in discussion about health care successes, challenges and opportunities for future partnerships. Our role and objectives Everything we do is about improving the health and wellness of Albertans, no matter what part of the province they live in. We: • Are a group of volunteers focused on listening to your thoughts and ideas on health services to help AHS enhance care locally and province wide. • Develop partnerships between the province’s diverse communities and AHS. • Provide feedback about what is working well within the health care system and suggest areas for improvement. • Promote opportunities for members of our local communities to get engaged. Join us - your voice matters There are a number of opportunities to participate, visit ahs.ca and search Health Advisory Councils for more info: • Attend an upcoming council meeting to hear feedback, offer comments, and ask questions. -

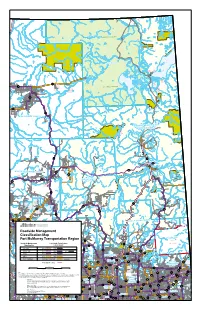

Roadside Management Classification

I.R. I.R. 196A I.R. 196G 196D I.R. 225 I.R. I.R. I.R. 196B 196 196C I.R. 196F I.R. 196E I.R. 223 WOOD BUFFALO NATIONAL PARK I.R. Colin-Cornwall Lakes I.R. 224 Wildland 196H Provincial Park I.R. 196I La Butte Creek Wildland P. Park Ca ribou Mountains Wildland Provincial Park Fidler-Greywillow Wildland P. Park I.R. 222 I.R. 221 I.R. I.R. 219 Fidler-Greywillow 220 Wildland P. Park Fort Chipewyan I.R. 218 58 I.R. 5 I.R. I.R. 207 8 163B 201A I.R . I.R. I.R. 201B 164A I.R. 215 163A I.R. WOOD BU I.R. 164 FFALO NATIONAL PARK 201 I.R Fo . I.R. 162 rt Vermilion 163 I.R. 173B I.R. 201C I.R. I.R. 201D 217 I.R. 201E 697 La Crete Maybelle Wildland P. Park Richardson River 697 Dunes Wildland I.R. P. Park 173A I.R. 201F 88 I.R. 173 87 I.R. 201G I.R. 173C Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park I.R. 174A I.R. I.R. 174B 174C Marguerite River Wildland I.R. Provincial Park 174D Fort MacKay I.R. 174 88 63 I.R. 237 686 Whitemud Falls Wildland FORT Provincial Park McMURRAY 686 Saprae Creek I.R. 226 686 I.R. I.R 686 I.R. 227 I.R. 228 235 Red Earth 175 Cre Grand Rapids ek Wildland Provincial Park Gipsy Lake I.R. Wildland 986 238 986 Cadotte Grand Rapids Provincial Park Lake Wildland Gregoire Lake Little Buffalo Provincial Park P. -

Voice 2011 04Augsept.Pdf

! The FREE 15 Yearsand & stillCounting... Appalachian August/September 2011VOICE From backyard chicken coops and community kitchens to logging with horses Living and existing completely off the grid, the back-to-the-land movement is broader— Land and more popular—than you think. ALSO INSIDE: Three Weeds to Feed Your Needs • Microhydro • The Art of Mushrooming The Appalachian A Note From the Executive Director Dear Readers, VOICE The majority of Americans anticipate a bright future of renewable A publication of AppalachianVoices energy and energy efficiency, and an end to pollution of our water, air and land. Yet Congress is out of touch with this vision, working instead to take 191 Howard Street • Boone, NC 28607 1-877-APP-VOICE us back to pre-1972 America, when rivers caught fire, swimming could be www.AppalachianVoices.org hazardous to your health and smog routinely killed people. [email protected] Forward Thinkers Move Back to the Land Sound’s crazy, right? Not when you realize that last week, the U.S. By Rachael Goss of activism shared by many of the Appalachian Voices is committed to protecting the land, air homesteaders. House of Representatives actually passed a bill—the Clean Water Coopera- When we think about the 1960s, ...................................................................................... 10 and water of the central and southern Appalachian region. A New Twist on Husbandry In the 1970s, as the national Our mission is to empower people to defend our region’s rich tive Federalism Act of 2011 (HR 2018)—revoking the federal government’s certain iconic images pop up. From Appalachian Colleges Plant Seeds of Sustainability ................. -

1 Historie a Vývoj Mtv

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce 2011 Eliška Junková Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce Globalizační fenomén MTV Eliška Junková Plzeň 2011 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra sociologie Studijní program Sociologie Studijní obor Sociologie Bakalářská práce Globalizační fenomén MTV Eliška Junková Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Stanislav Holubec, Ph.D. Katedra sociologie Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2011 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a pouţila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2011 ……………………… Ráda bych poděkovala PhDr. Stanislavu Holubcovi, Ph.D. za odborné vedení při psaní této práce, za cenné rady a připomínky. Obsah 0 ÚVOD.............................................................................................. 1 1 GLOBALIZACE MÉDIÍ .................................................................. 4 1.1 KATEGORIE WORLD MUSIC ........................................................ 5 2 HISTORIE A VÝVOJ MTV ............................................................ 7 2.1 BREAKING THE COLOR BARRIER .................................................. 9 2.2 PRONIKÁNÍ HUDEBNÍCH ŽÁNRŮ NA MTV ..................................... 10 2.3 MUSIC AWARDS A FENOMÉN MADONNA ..................................... 12 2.4 KAMPANĚ MTV........................................................................... 14 3 GLOBALIZACE MTV ................................................................... 14 3.1 EXPANZE -

Product Guide

Publisher of Rural Heritage Magazine ProductAn abbreviated list of our mostGuide popular items. For a complete list go to www.mischka.com/shop Toll Free Phone 1-877-647-2452 Fax: (319) 449-4148 Publisher of Rural Heritage Magazine www.mischka.com Order online at www.mischka.com Prices and availability subject to change www.ruralheritage.com1 THE MISCHKAS CALENDARS Publisher of Rural Heritage Magazine Publisher of Rural Heritage Magazine • They make excellent gifts! • Made in the USA • Outstanding photography The Mischka’s story • Practical design • Durable Nearly 40 years ago, Bob and Mary Mischka, with the help of their five boys, were raising 30 head of Percherons on their southeast 2019 Wall & Appointment Calendar Quanity prices: Wisconsin farm. When they couldn’t find a calendar to celebrate their 1: $16.95 love of draft horses, they made their own and started selling it out of 2: $30 ($15 ea) their home. That small endeavor turned into Mischka Press ... selling 3: $45 ($15 ea) Draft Horse, Driving Horse, Mule and Donkey wall calendars, an 4: $58 ($14.50 ea) FREE appointment calendar and a small desk calendar. Early on, giving our 5: $72.50 ($14.50 ea) SHIPPING! calendars became a holiday tradition for families across the country. 6: $84 ($14 ea) 7: $98 ($14 ea) The Mischkas added books and videos both commemorating our past 8: $108 ($13.50 ea) and celebrating those who continue 9: $121.50 ($13.50 ea) to use the skills of yesterday to do 10+: $13 each the work of today. Their son, Joe, and his wife, Susan, took over the business about 15 years ago and Wall calendars: 12 x 19 inches when open subsequently acquired Rural Heritage Magazine .. -

Timber Tongues

December 2013 The Official British Horse Loggers Newsletter Timber Tongues In this issue: Chair’s Report 2 Kate Mobbs-Morgan Using a Two-Horse 2 Forwarder John Bunce Tribute to Kyle 3 Colette Kyle BHL AGM and Annual 3 Competitions 2014 Letters in Response to 4/5 Forestry Journal’s “Wrong Priorities” Pete Harmer, Chris Wadsworth and Kate Mobbs-Morgan Working Horse 6 Harness and Fitting Demonstration Weekend Timber extraction demonstration during the Confor Woodland Show on the Rebecca Corrie-Close Longleat Estate — Kate Mobbs-Morgan with Kipp The New BHL Website 6 — Going Live! Confor Woodland Show — Kate Mobbs-Morgan Matt Waller Horse loggers were a popular sight at the Confor Woodland Show on 12th and 13th The Harness Maker’s 7 September at Longleat, Wiltshire, demonstrating the low-impact option for working Story in woodlands. Peter Coates There was much interest in the demonstrations and it was an excellent opportunity for visitors to ask questions and learn about the possibilities of using horses in for- Becoming a Horse 8 estry. Logger The three teams were Richard Branscombe from Swainsford Heavy Horses with his Chris Wadsworth grey Percheron mare Annabel; Kate Mobbs-Morgan from Rowan Working Horses APF 2014 9 with her roan Ardennes gelding Kipp; and Richard Eames from Richard Eames Pete Harmer Horse Logging with his piebald Traditional Cob mare Elizabeth. The Longleat estate had kindly felled a quantity of softwoods allowing the horses to Horse Logging in 9/10 demonstrate two working systems, showing how fast the horses can extract on a Japan good site, and how the timber can be lifted on an arch to minimise damage and re- Doug Joiner duce the impact on the ground.