IPCA Short Report Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Taranaki Regional Public Transport Plan 2020-2030

Draft Regional Public Transport Plan for Taranaki 2020/2030 Taranaki Regional Council Private Bag 713 Stratford Document No: 2470199 July 2020 Foreword (to be inserted) Table of contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Strategic context 2 2.1. Period of the Plan 4 3. Our current public transport system 5 4. Strategic case 8 5. Benefits of addressing the problems 11 6. Objectives, policies and actions 12 6.1. Network 12 6.2. Services 13 6.3. Service quality 14 6.4. Farebox recovery 17 6.5. Fares and ticketing 17 6.6. Process for establishing units 19 6.7. Procurement approach for units 20 6.8. Managing, monitoring and evaluating unit performance 22 6.9. Transport-disadvantaged 23 6.10. Accessibility 24 6.11. Infrastructure 25 6.12. Customer interface 26 7. Proposed strategic responses 28 Appendix A: Public transport services integral to the public transport network 31 Appendix B: Unit establishment 34 Appendix C: Farebox recovery policy 36 Appendix D: Significance policy 40 Appendix E: Land Transport Management Act 2003 requirements 42 1. Introduction The Taranaki Regional Public Transport Plan (RPTP or the plan), prepared by Taranaki Regional Council (the Council), is a strategic document that sets out the objectives and policies for public transport in the region, and contains details of the public transport network and development plans for the next 10 years (2020-2030). Purpose This plan provides a means for the Council, public transport operators and other key stakeholders to work together in developing public transport services and infrastructure. It is an instrument for engaging with Taranaki residents on the design and operation of the public transport network. -

4. Ngamotu Domain Recreation Reserve

4. Ngamotu Domain Recreation Reserve Description Location: Pioneer Road, New Plymouth Legal description: Sect 1010 Grey District Lot 3 DP 9266 Lot 4 DP 9266 Size: 8.62 hectares Reserve Status: Subject to the Reserves Act 1977 Reserve Classification Recreation reserve Breakwater Road Pioneer Road Windy Point Reserve South Road SH45 Physical description Ngamotu Domain is a sports park located in Moturoa. Two vehicle accesses are located off Pioneer Road with additional pedestrian access from SH 45 South Road and Otaka Street (an unformed street) which is off SH 44 Breakwater Road. The sports park has two fields available. The current sport played at the park is rugby league. The eastern side of the park is Open Space A Environment Area in the District Plan. These areas are used primarily for organised sports and recreation. Such areas will normally have associated buildings such as clubrooms, changing sheds or toilet Parks Sports Parks Management Plan New Plymouth District Council 2012 facilities. To the West is Open Space B Environment Area which is characterised by those areas that are predominantly focused towards informal recreational pursuits, usually of a more passive nature, such as walking and playing. They are more open, with less built features than the Open Space A Environment Area. The park is surrounded by a mix of Residential A and B Environment Areas, Industrial D to the north and Motorua Primary School to the northwest. Tangata whenua interests This reserve is within the tribal rohe of Te Atiawa and Taranaki Iwi. It is of historic and cultural significance to Ng āti Te Whiti and Ng ā Mahanga-a-Tairi hap ū. -

Non-Notified, Limited Notified and Publicly Notified Consents Issued

Non-notified authorisations issued by the Taranaki Regional Council between 09 Nov 2018 and 24 Jan 2019 Coastal Permit Consent Holder Subtype Primary Industry Purpose R2/10683-1.1 OMV NZ Production Limited Discharge to water (CMA) Hydrocarbon Exploration R2/6222-2.0 South Taranaki District Council Discharge (Coastal) Building Construction/Drainage/Flood Control R2/10702-1.0 South Taranaki District Council Structure - Outfall (Coastal) Sewage Treatment Discharge Permit Consent Holder Subtype Primary Industry Purpose R2/1281-4.0 JD Hickman 1997 Family Trust Water - Stormwater Transport Operator R2/0969-3.0 Shantilly Farms Limited Land - animal waste Dairy Farm R2/10700-1.0 Aviagen New Zealand Limited Land - animal waste Poultry Farm R2/10483-1.0 Greymouth Petroleum Central Limited Land - DWI Energy R2/10699-1.0 Oscar4U Air - Abrasive Blasting Abrasive Blasting R2/3177-3.0 Crosbig Trusts Partnership Water - Animal Waste Dairy Farm R2/0526-4.0 South Taranaki District Council Water - Stormwater Landfill R2/1181-3.0 Forrit Farms Limited Land - animal waste Dairy Farm R2/0363-4.0 Udder Trust Water - Animal Waste Dairy Farm R2/1661-4.0 Esternwest Farms Limited Water - Animal Waste Dairy Farm R2/10704-1.0 New Plymouth District Council Land - stormwater Building Construction/Drainage/Flood Control R2/10693-1.0 Waitomo Energy Limited Land - Industry Service Station R2/7905-1.1 Westside New Zealand Limited Land - Industry Hydrocarbon Exploration R2/7559-1.4 Colin David Boyd Land - Land Farming Hydrocarbon Exploration Servicing Facilities R2/7591-1.2 -

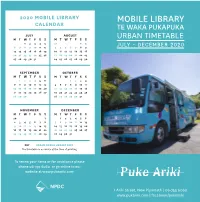

Mobile-Library-Timetable Urban-2 2020-Website.Pdf

2020 MOBILE LIBRARY MOBILE LIBRARY CALENDAR TE WAKA PUKAPUKA JULY AUGUST M T W T F S S M T W T F S S URBAN TIMETABLE 1 2 3 4 5 31 1 2 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 JULY - DECEMBER 2020 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 SEPTEMBER OCTOBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31 NOVEMBER DECEMBER M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 30 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 28 29 30 31 KEY URBAN MOBILE LIBRARY DAYS The timetable is accurate at the time of printing To renew your items or for assistance please phone 06-759 6060 or go online to our website at www.pukeariki.com 1 Ariki Street, New Plymouth | 06-759 6060 www.pukariki.com | facebook/pukeariki MOBILE LIBRARY URBAN TIMETABLE JULY - DECEMBER 2020 The Mobile Library/Te Waka Pukapuka stops at a street near you every second week. -

Inventory of Coastal Areas of Local Or Regional Significance in the Taranaki Region

Inventory of coastal areas of local or regional significance in the Taranaki Region Taranaki Regional Council Private Bag 713 Stratford January 2004 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PURPOSE...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 SCOPE.......................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. METHODOLOGY........................................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 SITES OF LOCAL OR REGIONAL SIGNIFICANCE.............................................................................................. 2 2.2 SUBDIVISIONS.............................................................................................................................................. 2 2.3 UNFORMED ROADS ...................................................................................................................................... 3 3. INVENTORY SHEETS................................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NUMBER..................................................................................................................................................... -

List of Submitters and Contact Details – Alphabetical Order

List of Submitters and Contact Details – alphabetical order Subm Submitter Address1 Address2 City Email No 220 4Site Design - Sharron Betts on behalf of Paul 495B Devon St East Strandon New Plymouth 4312 [email protected] Rust, Architectural Designer 585 Aaron Hine and Rachael Hareb-Hine 15 Wairau Road Oakura [email protected] 97 Abbie Jury 589 Otaraoa Road RD 43 Waitara 4383 [email protected] 150 Adam Parker 94 Dixon Street Wellington 6011 [email protected] 445 Adil Riaz 6 Downe Street New Plymouth [email protected] 498 Afforestation (New Zealand) Limited (ANZL) - 31 McAdam Road Waipu 0582 [email protected] Allan Beverwijk 477 Aggregate & Quarry Association of New C/- Mitchell Daysh Ltd Manakau Auckland 2241 [email protected] Zealand - Graeme Mathieson PO Box 97431 316 Airbnb - Louise Trevena-Downing 18 Viaduct Harbour Auckland City Auckland 1010 [email protected] Avenue 187 Alan and Sherril Moody PO Box 41 Waitara [email protected] 242 Alexandra Thompson 110A Wairau Road Oakura New Plymouth [email protected] 362 Alistair and Michelle Shanks 150 Cliff View Drive Green Bay Auckland 0604 [email protected] 301 Alistar Jordan 453 Maude Road Korito New Plymouth 4371 [email protected] 158 Allan Barrett 778 Plymouth Road Koru New Plymouth 4374 [email protected] 331 Allan Bruce Findlay PO Box 115 Urenui [email protected] 147 Allen Juffermans PO Box 193 New Plymouth 4314 [email protected] 320 Amanda McGregor 6 Aubrey Street New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] -

Heritage Strategy

Heritage Strategy ‘A district that values, recognises and cares for its heritage resources’ Tukotahi carving Puke Ariki Landing Pöhutukawa trees Kawaroa Heritage Strategy 1 Exhibition at Puke Ariki Contents Introduction ......................................................................................3 - Trees ......................................................................................21 Why is a heritage strategy needed? ..............................................3 - Signifi cant natural areas .........................................................21 - Recreational use of natural areas .........................................21 About the heritage strategy ...........................................................4 - Waterways ..............................................................................22 Defi ning heritage .............................................................................5 Cultural heritage .......................................................................23 The role of the Council ....................................................................6 - Archaeological and waahi tapu sites .....................................23 Working together .............................................................................8 - Puke Ariki heritage collections ..............................................25 Tangata Whenua ..............................................................................9 - Taonga held in private collections ..........................................26 Vision -

List of Further Submitters and Contact Details – Alphabetical Order

List of Further Submitters and Contact Details – alphabetical order Further Further Submitter Address1 Address2 City Email Subm No FS 2 Allan Stanley Gargan 33 Beach Road Waireka [email protected] FS 188 Allen Juffermans PO Box 193 New Plymouth [email protected] FS 153 Andrea Cook 24 Porritt Drive Kawerau 3127 [email protected] FS 54 Andrew and Catherine Clennett 15 Lismore Street New Plymouth [email protected] FS 86 Andrew and Sarah Birchler PO Box 511 New Plymouth 4340 [email protected] FS 154 Anthony Drake 12A Victoria Road New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] FS 91 Ara Poutama Aotearoa (Department of Corrections) Private Box 1206 Wellington 6140 [email protected] FS 194 Ashley Lawry 33 Saxton Road Vogeltown New Plymouth [email protected] FS 28 Bach Break 477A/6 Devon Street East Strandon New Plymouth [email protected] FS 155 Ben Naughton 59 Record Street Fitzroy New Plymouth 4312 [email protected] FS 189 Bennie Prinsloo 31A Truby King Street Merrilands New Plymouth [email protected] FS 190 BJB Trust Holdings and PR Franklin 46A David Street New Plymouth FS 156 Bland and Jackson Surveyors on behalf of Cadess 19 Dawson Street New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] Properties Ltd FS 134 Bluehaven Commercial Limited PO Box 551 New Plymouth 4340 [email protected] FS 143 Bradburn Assets Limited PO Box 8235 New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] FS 21 Brent G May and Angela K May and GQ Trustees Ltd 363 Devon Street East New Plymouth 4312 [email protected] FS 99 Bridget Fraser and Mia -

Neural Tube Defects at Westown Maternity Hospital, 1965-72

Neural Tube Defects At Westown Maternity Hospital, 1965-72 A Report to the Taranaki District Health Board Prepared by Dr Patrick O’Connor Medical Officer of Health August 2002 Table of Contents Executive Summary _____________________________________________________ 3 Introduction ___________________________________________________________ 4 Neural Tube Defects ____________________________________________________ 5 Genetic factors _____________________________________________________________ 5 Reproductive and Family History ______________________________________________ 5 Socio-economic factors _______________________________________________________ 5 Diet _______________________________________________________________________ 5 Environmental & Occupational factors _________________________________________ 5 Herbicides and dioxin________________________________________________________ 6 Monitoring of Birth Defects and Neural Tube Defects in NZ ____________________ 7 2,4,5-T Production at Ivon-Watkins-Dow____________________________________ 8 Results_______________________________________________________________ 10 Discussion____________________________________________________________ 19 Conclusions __________________________________________________________ 21 Recommendations _____________________________________________________ 21 Acknowledgements_____________________________________________________ 21 References ___________________________________________________________ 22 Executive Summary This study is one of a number that have investigated, -

Restoration Planting in Taranaki

CONTENTS Part one: Getting started Introduction .................................................................... 2 Ecological Regions and Districts of Taranaki .................... 3 Plan of Action ................................................................. 4 Part two: Target ecosystems Vegetation patterns .........................................................9 What to plant and where ...............................................11 Coastal Spinifex duneland ..........................................................13 Harakeke–raupo–kuta wetland .......................................14 Saltmarsh ribbonwood–oioi estuary shrubland ..............15 Taupata–kawakawa–harakeke/wharariki shrubland ........16 Coastal herbfield ...........................................................17 Tainui forest ...................................................................18 Karaka-tawa–puriri forest ...............................................19 Coastal–semi-coastal Kahikatea–pukatea swamp/semi-swamp forest .......... 21 Kohekohe–karaka–puriri forest .......................................22 Semi-coastal–lowland Manuka–Gaultheria–wharariki shrubland .......................23 Tawa forest .....................................................................24 Tawa–pukatea forest ......................................................25 Lowland Tawa–kamahi forest .......................................................27 Hard beech and black beech forest ................................28 Waitaanga area silver beech–kamahi forest....................29 -

List of Submitters and Contact Details – Numerical Order

List of Submitters and Contact Details – numerical order Subm Submitter Address1 Address2 City Email No 1 Sefton Judd 10 Patterson Road RD 1 New Plymouth 4371 [email protected] 2 Mervyn MacKay 18a Kauri Street Inglewood 4330 [email protected] 3 Richard Martin 48 Watson Street Strandon New Plymouth 4312 [email protected] 4 Cassandra Scott 88 Huatoki Street Vogeltown New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 5 Frank Lachmann 427 Mataro Road RD 45 Urenui 4375 [email protected] 6 Rex Hendry 804 Egmont Road RD 2 Hillsborough New Plymouth 4372 [email protected] 7 Stuart Christensen 88 Huatoki Street Vogeltown New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 8 Geoff and Kaddy Smale 27 Fillis Street New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 9 Shaun and Lorena Brannigan 114 Carrington Street New Plymouth [email protected] 10 Elaine Gill 241D Frankley Road New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 11 Daryl Hine 477 Carrington Street New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 12 Stephen Honeyfield 504 Patea Road RD 1 Patea 4597 [email protected] 13 Thandi Tipene 17 Shearer Drive Oakura 4314 [email protected] 14 Heather Pantin-Lewis 14B Omata Road New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 15 Richard Porter 102 Buller Street New Plymouth 4312 [email protected] 16 Marilyn Powell 174 Powderham Street New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 17 Robyn and Blair Burnett 224 Hurford Road RD 4 Omata New Plymouth 4374 [email protected] 18 Anna Major 13 Lorna Street Lynmouth New Plymouth 4310 [email protected] 19 Stefan -

Museums and Galleries

MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES Free Copy or download at www.visit.taranaki.info 5th Edition Ahititi Okau Pukearuhe 3 Mi Welcome W mi a Ri i ve ta Ur r Uruti ra en W u From the mythical volcanic cone of Mount Taranaki to the ancient R i R a iv i iw e ve h r r a pā sites that mark the region’s hilltops to the innovation of its k Motunui a ih o Waitara residents, Taranaki is home to countless great stories, which are Onaero R Brixton Urenui iv Bell Block e Okoki best told through its many museums and galleries. As you r New Plymouth Tikorangi work your way through the museums and galleries 3 11 Ta 17 pu Lepperton ae 10 9 8 Hillsborough listed in this Venture Taranaki publication, you’ll S 2 16 tr 14 ea 5 m d 3A n discover that the people of Taranaki are passionate a 13 l 3 p U P not only about collecting, but about sharing l y m Oakura o 6 u Hurworth t 4 the region’s history and its many fascinating h Waitui URF IGHWA R 12 H45Y Koro o a Egmont Village stories. For more information about d Tarata Sto 7 1 ny River U Tataraimaka Te Henui Kaimata pp Inglewood the region like no other, see e d r Korito a Pohokura Okato Pi o to R ne www.visit.taranaki.info. O R et Kaimiro m Puniho xf o re a o ad St h rd n r Ratapiko Pu R o u n o gt D ih ad in d W o rr a are R a o a R o C R iv ad Egmont t er Warea n o Tariki Tumahu m Cape Light and Museum 32 National g Te Wera E d a Kupe Huiroa o R Newall Park y North Egmont re W r Tuna Strathmore Su Te Popo i Lighthouse 32 Pungarehu r e itata Stream m Wa P u Mt Taranaki arihak a Road R Midhirst o a East Egmont d Wharehuia