AFLSSQ Review 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iconic Outback Pubs

Iconic Outback Pubs DAY 1: Sat 01 May 21 – MELBOURNE – GRIFFITH -Meet your driver/guide this morning and depart for Griffith, a major city servicing the Murrumbidgee Irriga on Area, located in the Riverina. Today is a travel day where you have the chance to chat to your fellow adventurers or watch the scenery roll by your window before arriving for a welcome dinner. Overnight: Griffith Farewell our hosts after breakfast this morning and travel to Bourke, situated on the banks of the Darling River. At the Back O’Bourke Exhibition Centre hear tales of early explorasion and the paddleboat trade. Learn about the local Aboriginal people of the region, farmers, stockman, bush poets, bushrangers and Afghan cameleers. Check into the accommodation with time to relax before dinner. Overnight: Bourke Crossing the border into Queensland visit the tiny town of Hungerford, which features a large border gate that doubles as a wild dog and dingo fence. Stop at the historic Royal Mail Hotel which was originally a Cobb & Co Staging Post where weary horses and travellers could rest from the harsh heat, road conditions and infrequent floods. This afternoon push through to Thargomindah. Overnight: Thargomindah DAY 2: Sun 02 May 21 GRIFFITH – BOURKE (BD) DAY 3: Mon 03 May 21 BOURKE – HUNGERFORD – THARGOMINDAH (BLD) DAY 4: Tue 04 May 21 EULO & TOOMPINE (BD) DAY 5: Wed 05 May 21 THARGOMINDAH – NOCCUNDRA – INNAMINCKA (BLD) Located on the banks of the Bulloo River, Thargomindah’s traditional source of industry is sheep and wool. In recent times, petroleum/oil and gas make up a large part of the region’s economy. -

South West Queensland Floods March 2010

South West Queensland Floods March 2010 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Floodwaters inundate the township of Bollon. Photo supplied by Bill Speedy. 2. Floodwaters at the Autumnvale gauging station on the lower Bulloo River. Photo supplied by R.D. & C.B. Hughes. 3. Floodwaters from Bradley’s Gully travel through Charleville. 4. Floodwaters from Bungil Creek inundate Roma. Photo supplied by the Maranoa Regional Council. 5. Floodwaters at the confluence of the Paroo River and Beechal Creek. Photo supplied by Cherry and John Gardiner. 6. Balonne River floodwaters inundate low lying areas of St. George. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. 7. Floodwaters from the Moonie River inundate Nindigully. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. 8. Floodwaters from the Moonie River inundate the township of Thallon. Photo supplied by Sally Nichol. Revision history Date Version Description 6 June 2010 1.0 Original Original version of this report contained an incorrect date for the main flood peak at Roma. Corrected to 23 June 2010 1.1 8.1 metres on Tuesday 2 March 2010. See Table 3.1.1. An approximate peak height has been replaced for Bradley’s Gully at Charleville. New peak height is 4.2 28 June 2010 1.2 metres on Tuesday 2 March 2010 at 13:00. See Table 3.1.1. Peak height provided from flood mark at Teelba on 01 July 2010 1.3 Teelba Creek. See Table 3.1.1. 08 Spectember Peak height provided from flood mark at Garrabarra 1.4 2010 on Bungil Creek. See Table 3.1.1. -

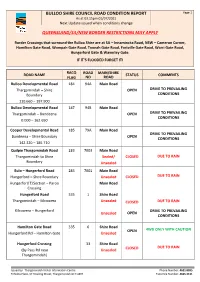

BULLOO SHIRE COUNCIL ROAD CONDITION REPORT Page 1 As at 03.15Pm 01/07/2021 Next Update Issued When Conditions Change

BULLOO SHIRE COUNCIL ROAD CONDITION REPORT Page 1 As at 03.15pm 01/07/2021 Next Update issued when conditions change QUEENSLAND/SA/NSW BORDER RESTRICTIONS MAY APPLY Border Crossings that surround the Bulloo Shire are at SA – Innamincka Road, NSW – Cameron Corner, Hamilton Gate Road, Wompah Gate Road, Toonah Gate Road, Fortville Gate Road, Warri Gate Road, Hungerford Gate & Waverley Gate. IF IT’S FLOODED FORGET IT! RACQ ROAD MAIN/SHIRE ROAD NAME STATUS COMMENTS FLAG NO ROAD Bulloo Developmental Road 184 94A Main Road Thargomindah – Shire OPEN DRIVE TO PREVAILING CONDITIONS Boundary 110.660 – 197.900 Bulloo Developmental Road 187 94B Main Road Thargomindah – Bundeena OPEN DRIVE TO PREVAILING CONDITIONS 0.000 – 162.650 Cooper Developmental Road 185 79A Main Road DRIVE TO PREVAILING Bundeena – Shire Boundary OPEN CONDITIONS 142.320 – 185.710 Quilpie Thargomindah Road 183 7003 Main Road Thargomindah to Shire Sealed/ CLOSED DUE TO RAIN Boundary Unsealed Eulo – Hungerford Road 284 7001 Main Road Hungerford – Shire Boundary Unsealed CLOSED DUE TO RAIN Hungerford T/Section – Paroo Main Road Crossing Hungerford Road 335 1 Shire Road Thargomindah – Kilcowera Unsealed CLOSED DUE TO RAIN Kilcowera – Hungerford DRIVE TO PREVAILING Unsealed OPEN CONDITIONS Hamilton Gate Road 335 6 Shire Road OPEN 4WD ONLY WITH CAUTION Hungerford Rd – Hamilton Gate Unsealed Hungerford Crossing 33 Shire Road CLOSED DUE TO RAIN (By Pass Rd near Unsealed Thargomindah) Issued by: Thargomindah Visitor Information Centre Phone Number: 4621 8095 Echidna Place, 37 Dowling Street, Thargomindah QLD 4492 Facsimile Number: 4655 3131 BULLOO SHIRE COUNCIL ROAD CONDITION REPORT Page 2 As at 03.15pm 01/07/2021 Next Update issued when conditions change QUEENSLAND/SA/NSW BORDER RESTRICTIONS MAY APPLY Border Crossings that surround the Bulloo Shire are at SA – Innamincka Road, NSW – Cameron Corner, Hamilton Gate Road, Wompah Gate Road, Toonah Gate Road, Fortville Gate Road, Warri Gate Road, Hungerford Gate & Waverley Gate. -

Regional Area Surcharge

Toll Group Level 7, 380 St Kilda Road Melbourne VIC 3004 Australia Toll Transport Pty Ltd ABN: 31006604191 Regional Area Surcharge Regional area surcharges are applicable for pick up or delivery to regional, remote or off-shore locations where Toll incurs additional costs to service. Priority Service Suburb Postcode Price Abingdon Downs 4892 $ 51.50 Acacia Hills 0822 $ 26.00 Adavale 4474 $ 51.50 Adelaide River 0846 $ 26.00 Aherrenge 0872 $ 26.00 Alawa 0810 $ 26.00 Ali Curung 0872 $ 26.00 Alice Springs 0872 $ 26.00 Alice Springs 0870 $ 26.00 Almaden 4871 $ 51.50 Aloomba 4871 $ 51.50 Alyangula 0885 $ 26.00 Amata 0872 $ 26.00 American Beach 5222 $ 51.50 American River 5221 $ 51.50 Amoonguna 0873 $ 51.50 Ampilatwatja 0872 $ 26.00 Anatye 0872 $ 26.00 Andamooka 5722 $ 77.50 Anduramba 4355 $ 51.50 Angledool 2834 $ 51.50 Angurugu 0822 $ 26.00 Anindilyakwa 0822 $ 26.00 Anmatjere 0872 $ 26.00 Annie River 0822 $ 26.00 Antewenegerrde 0872 $ 26.00 Anula 0812 $ 26.00 Araluen 0870 $ 26.00 Archer 0830 $ 26.00 Archer River 4892 $ 51.50 Archerton 3723 $ 26.00 Area C Mine 6753 $ 51.50 Areyonga 0872 $ 26.00 Arnold 0852 $ 26.00 Arumbera 0873 $ 51.50 Ascot 4359 $ 77.50 Atitjere 0872 $ 26.00 Aurukun 4892 $ 51.50 Austinville 4213 $ 26.00 Avon Downs 0862 $ 26.00 Ayers Range South 0872 $ 26.00 Ayers Rock 0872 $ 26.00 Ayton 4895 $ 51.50 Badu Island 4875 $ 77.50 Bagot 0820 $ 26.00 1 Regional Area Surcharge (RAS) Baines 0852 $ 26.00 Bakewell 0832 $ 26.00 Balgowan 5573 $ 26.00 Balladonia 6443 $ 77.50 Balranald 2715 $ 77.50 Bamaga 4876 $ 77.50 Banks Island 4875 $ 77.50 -

DIVISION FINDER 2019 Division Finder

2019 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA 2019 DIVISION FINDER Division Finder Queensland QLD EF54 EF54 i © Commonwealth of Australia 2019 This work is copyright. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise, without the written consent of the Australian Electoral Commission. All enquiries should be directed to the Australian Electoral Commission, Locked Bag 4007, Canberra ACT 2601. ii iii Contents Instructions For Use And Other Information Pages v-xiii INTRODUCTION Detailed instructions on how to use the various sections of the Division Finder. DIVISIONAL OFFICES A list of all divisional offices within the State showing physical and postal addresses, and telephone and facsimile numbers. INSTITUTIONS AND ESTABLISHMENTS A list of places of residence such as Universities, Hospitals, Defence Bases and Caravan Parks. This list may be of assistance in identifying institutions or establishments that cannot be found using the Locality and Street Sections. Locality Section Pages 1-43 This section lists all of the suburbs, towns and localities within the State of Queensland and the name of the corresponding electoral division the locality is contained in, or the reference ... See Street Section. Street Section Pages 47-135 This section lists all the streets for those localities in the Locality Section which have the reference ... See Street Section. Each street listing shows the electoral division the street is contained in. iv v Introduction The Division Finder is the official list used to Electors often do not know the correct identify the federal electoral division of the federal division in which they are enrolled, place an elector claims to be enrolled at. -

Birdsville from Brisbane to Birdsville

Destination: Birdsville From Brisbane to Birdsville This guide will provide two routes you can take from Brisbane to Birdsville for the Big Red Bash, including recommendations on what you can see and do on your journey. Both of these road trips cover a great distance and are therefore split up over a number of days to ensure you make the most of what Queensland’s outback regions have to offer. Make sure to check that your car is in good condition and that you are well stocked with extra fuel and water. 4WD’s are generally recommended for outback driving. Head to www.bigredbash.com.au for more outback driving tips. Route 1 From outdoor galleries to artesian mud baths and out to the most remote areas of South Australia, this journey shows you what Australia is all about! Route one will take you approximately 27 hours driving time or leisurely sightseeing over 4 days down the southern border of Queensland and the northeast corner of South Australia. Brisbane to Goondwindi (Approximately 4 hours) • First stop is Queensland’s Garden City, Toowoomba, for a scenic picnic lunch at Toowoomba's heritage-listed Picnic Point Lookout and Parkland which comprises of 160-acres of land perched high on the crest of the Great Dividing Range, with panoramic views over Main Range and Lockyer Valley. • The First Coat festival has transformed Toowoomba into one of Australia’s largest outdoor galleries with over 70 large-scale murals scattered throughout the heart of the city. • Home to the award winning ‘Carnival of Flowers’ Festival, you’ll also want to ensure that you stroll through the city’s Queens Park close by to the Cobb & Co Museum. -

His Month to Have the Hon Mark Furner, Minister for Agriculture, Industry Development and Fisheries (DAF) Visit with Council on Tuesday 27/8/2019

Bulloo Buzz 4 September 2019 MAYORS MESSAGE ……………..………….………………………. We were fortunate this month to have the Hon Mark Furner, Minister for Agriculture, Industry Development and Fisheries (DAF) visit with Council on Tuesday 27/8/2019. He had been to Charleville and Quilpie and came out here to meet with Council as well as Mr Anthony Glasson to discuss Mr Glasson’s work with Merino Sheep and current trends in the sheep industry. The Minister was impressed with the work that was happening in Thargo and he was very interested in the Warri Gate road project and the development of the Low Care Independent Living Centre. I informed him that we couldn’t ever remember an Agricultural Minister coming to Bulloo and the last State Minister was Minister Crisafulli who opened the VIC when the National Party was in Government. At Council’s last Ordinary and Special meetings, we approved the purchase of three utilities, a Prado, 1 Landcruiser, 2 Caterpillar Multi Tyred Rollers and 1 Caterpillar 12m Grader. All up this was a total spend of $1.1 million. This is part of Council’s commitment to ensure that we have a modern fleet of vehicles and plant that reduces our Maintenance and gives us a better resale value when we come to trade them in. It also gives local people the opportunity to buy vehicles at a reduced cost that they know have been serviced regularly. We have more plant to purchase but these are our major items for this year. The CEO attended a SWRED meeting in Cunnamulla last week. -

Regional-Map-Outback-Qld-Ed-6-Back

Camooweal 160 km Burke and Wills Porcupine Gorge Charters New Victoria Bowen 138° Camooweal 139° 140° 141° Quarrells 142° 143° Marine fossil museum, Compton Downs 144° 145° 146° Charters 147° Burdekin Bowen Scottville 148° Roadhouse 156km Harrogate NP 18 km Towers Towers Downs 80 km 1 80 km 2 3 West 4 5 6 Kronosaurus Korner, and 7 8 WHITE MTNS Warrigal 9 Milray 10 Falls Dam 11 George Fisher Mine 139 OVERLANDERS 48 Nelia 110 km 52 km Harvest Cranbourne 30 Leichhardt 14 18 4 149 recreational lake. 54 Warrigal Cape Mt Raglan Collinsville Lake 30 21 Nonda Home Kaampa 18 Torver 62 Glendower NAT PARK 14 Biralee INDEX OF OUTBACK TOWNS AND Moondarra Mary Maxwelton 32 Alston Vale Valley C Corea Mt Malakoff Mt Bellevue Glendon Heidelberg CLONCURRY OORINDI Julia Creek 57 Gemoka RICHMOND Birralee 16 Tom’s Mt Kathleen Copper and Gold 9 16 50 Oorindi Gilliat FLINDERS A 6 Gypsum HWY Lauderdale 81 Plains LOCALITIES WITH FACILITIES 11 18 9THE Undha Bookin Tibarri 20 Rokeby 29 Blantyre Torrens Creek Victoria Downs BARKLY 28 Gem Site 55 44 Marathon Dunluce Burra Lornsleigh River Gem Site JULIA Bodell 9 Alick HWY Boree 30 44 A 6 MOUNT ISA BARKLY HWY Oonoomurra Pymurra 49 WAY 23 27 HUGHENDEN 89 THE OVERLANDERS WAY Pajingo 19 Mt McConnell TENNIAL River Creek A 2 Dolomite 35 32 Eurunga Marimo Arrolla Moselle 115 66 43 FLINDERS NAT TRAIL Section 3 Outback @ Isa Explorers’ Park interprets the World Rose 2 Torrens 31 Mt Michael Mica Creek Malvie Downs 52 O'Connell Warreah 20 Lake Moocha Lake Ukalunda Mt Ely A Historic Cloncurry Shire Hall, 25 Rupert Heritage listed Riversleigh Fossil Field and has underground mine tours. -

2021 Land Valuations Overview Murweh

Land valuations overview: Murweh Shire Council On 31 March 2021, the Valuer-General released land valuations for 2,358 properties with a total value of $508,701,560 in the Murweh Shire Council area. The valuations reflect land values at 1 October 2020 and show that Murweh Shire has increased by 75 per cent overall since the last valuation in 2018. Rural land values have increased significantly due to the strength in beef commodity prices as well as a low interest rate environment. Due to the decline in western towns and the effects of a prolonged drought, residential values in Charleville have experienced moderate to significant reductions. Inspect the land valuation display listing View the valuation display listing for Murweh Shire Council online at www.qld.gov.au/landvaluation or visit the Department of Resources, Hood Street, Charleville. Detailed valuation data for Murweh Regional Council Valuations were last issued in the Murweh Shire Council area in 2018. Property land use by total new value Residential land Table 1 below provides information on median values for residential land within the Murweh Shire Council area. Table 1 - Median value of residential land Residential Previous New median Change in Number of localities median value value as at median value properties as at 01/10/2020 (%) 01/10/2017 ($) ($) Augathella 4,700 4,700 0.0 166 Bakers Bend 200 200 0.0 1 Charleville 12,200 9,800 -19.7 1,296 Cooladdi 3,000 3,000 0.0 2 Langlo 750 750 0.0 2 Morven 11,200 13,500 20.5 96 All residential 12,000 9,600 -20.0 1,563 localities Explanatory Notes: The town of Charleville has generally experienced moderate reductions in residential lands. -

Central and Western Queensland Floods January 2008

Central and Western Queensland Floods January 2008 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Clockwise from top left; 1. Flooded roads around Proserpine. 2. Burdekin Falls Dam 3. Giru flooding from the Air. (newsdotcom) 4. Cars washed off road near Giru. 5. Bradleys Gully floods Charleville. 6. Nogoa River at Fairbairn Dam 7. Dragline and coal mine flooded by the Nogoa River 8. Houses flooded in Emerald. All photos are sourced from the Internet via www or email. Note: 1. Data in this report has been operationally quality controlled but errors may still exist. 2. This product includes data made available to the Bureau by other agencies. Separate approval may be required to use the data for other purposes. See Appendix 1 for DNRW Usage Agreement. 3. This report is not a complete set of all data that is available. It is a representation of some of the key information. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Figure 1.1 Peak Height Map for January 2008 - Queensland.................................................................. 3 2. Meteorological Summary ............................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Meteorological Analysis......................................................................................................................... 4 Figure 2.1.1 Track of Tropical Low Pressure System from the 9 – 18 January 2008............................... -

Name of Department (Times New Roman 12Pt/Bold)

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 Aspects of the contemporary and Quaternary hydrology of the Lake Eyre Basin, central Australia Joshua Redder Larsen University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Larsen, Joshua Redder, Aspects of the contemporary and Quaternary hydrology of the Lake Eyre Basin, central Australia, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3538 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. Aspects of the contemporary and Quaternary hydrology of the Lake Eyre Basin, central Australia Joshua Redder Larsen This thesis is presented as part of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy From the School of Earth & Environmental Sciences University of Wollongong November 2011 THESIS DECLARATION I, Joshua Redder Larsen, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment for the requirements for the award of the award of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise acknowledged. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. The chapters of this thesis constitute papers submitted or published within academic journals, and where co-authors are present remain approximately 80% my own work. I developed the ideas, aims and methods for each chapter, conducted all the analysis, and wrote all the text. Whist this text was subject to the review of my supervisors, co-authors, editors and journal reviewers, in general this only changed the presentation and interpretation of results and not the overall aims, methods, or conclusions. -

South West District

142°0'E CENTRAL WESTERN DISTRICT 144°0'E # 146°0'E 148°0'E # FITZROY DISTRICT 150°0'E 7 ! ! 1 d E 4 ! oa 6 B 6 R 4 t " D 2 C 5 Banana 5 e B Birkhead 87A A Bauhinia d m AR D O Em COO EV R " 8 ! Thangool R # North CUNNAMULLA CENTRAL HIGHLANDS B 13A LANDSBOROUGH HIGHWAY 36B BALONNE HIGHWAY DIAMANTINA St 3 Moura DAWSON - R # 0 4 # 959 R 776 ll 1 O 6C CENTRAL # ka 1 3 REGIONAL COUNCIL 637 # (Morven - Augathella) (Bollon - Cunnamulla) W E Ra c C SHIRE COUNCIL ilw a W # ay S Bl 7 R " # a V t 4 I ! IV 1 ll E N Cungelella 225 638 N 1196 13B LANDSBOROUGH HIGHWAY! Y 37A CASTLEREAGH HIGHWAY D a # C # R k 223 n R 642 # m A O ! A o ! PAROO e l A l F 7 S Kianga lo Emmet (Augathellae - Tambo) (Noondoo - Hebel) t re W o nc 771 R r t 8 WOORABINDA S t e # A B S W S t SHIRE COUNCIL H S C N ! 6 d Moonford t A 18D WARREGO HIGHWAY 2 79A COOPER DEVELOPMENTAL ROAD M a G - n ab LONGREACH A 8 " BALONNE el S 553 D ABORIGINAL I ! a o 5 t e l v S m 253 I e t R A l t R D H ek n a S n Cre e i (Miles - Roma) (Quilpie - Bundeena) a B BLACKALL-TAMBO S l 1018 REGIONAL V Coominglah J E l " o A h SHIRE COUNCIL # m i y # SHIRE COUNCIL n m 3 t e a ! r l c ! W t 601 O a t 94 ! s s 2 i A # W a Y ! ## # Ca t 18E WARREGO HIGHWAY 86A SURAT DEVELOPMENTAL ROAD W REGIONAL COUNCIL w Lo S H B ! COUNCIL N d S t M M u 271 975 i e 203 s t 6 e S 1 R n O 112 t 3 k u S e o d 3 E R Cre R S St 208 Ta m b o # (Roma - Mitchell)N (Surat - Tara) t L R C MITCHEL 241 B IV 1016 3 k n 9 # R # 6B S 4A C h 36 d A R n 639 18F WARREGO HIGHWAY 93A DIAMANTINA DEVELOPMENTAL ROAD A 2 a Carnarvon o lic 3A e