Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Sports – Opportunities for UK Companies South Korea

Opportunity Korea Global Sports – Opportunities for UK companies South Korea South Korea In the next four years Korea will see an unprecedented level of activity at the host the Asian Games in Incheon, the Universiade in Gwangju, the IOC Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang and the FISU World Swimming Championships in Gwangju. Korea is no stranger to hosting global sports events, and it has hosted (amongst others): 1986 - Asian Games in Seoul 1988 - IOC Summer Olympics in Seoul 2002 - FIFA Football World Cup 2002 - Asian Games in Busan 2011 - IAAF World Athletics Championship in Daegu Incheon Asian Games – Sept 2014 changes at the top of the committee. Gwangju Universiade – July 2015 The Asian Games are larger in scale South-Western city Gwangju will host than the Summer Olympics, While the Incheon Committee was the summer Universiade (World consisting of 36 sports, around 13,000 impressed by the UK’s staging of the Student Games) in July 2015. The athletes and officials and 7,000 London Olympics in 2012, much of games will feature 21 sports and host broadcasters. The organising UK’s good work will have come a little 7,000 athletes from 170 countries. committee of the Incheon Games has too late to influence the Incheon stated it will use a mixture of existing committee who have been driven by Four new venues (including the and new venues. The main stadium low cost options. British companies swimming complex which will be used has been designed by UK company have delivered some technical for the FISU World Swimming Populous (the designers of the solutions, may be involved in the Championships in 2019) will be built, stadium at Stratford). -

Appendix a Stations Transitioning on June 12

APPENDIX A STATIONS TRANSITIONING ON JUNE 12 DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LICENSEE 1 ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (D KTXS-TV BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. 2 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC 3 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC 4 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 5 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC 6 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 7 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC 8 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC 9 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 10 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 11 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CW KASY-TV ACME TELEVISION LICENSES OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 12 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM UNIVISION KLUZ-TV ENTRAVISION HOLDINGS, LLC 13 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM PBS KNME-TV REGENTS OF THE UNIV. OF NM & BD.OF EDUC.OF CITY OF ALBUQ.,NM 14 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM ABC KOAT-TV KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. 15 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM NBC KOB-TV KOB-TV, LLC 16 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CBS KRQE LIN OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 17 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM TELEFUTURKTFQ-TV TELEFUTURA ALBUQUERQUE LLC 18 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE CARLSBAD NM ABC KOCT KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. -

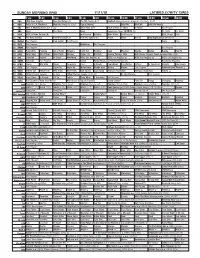

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

A Sociocultural Analysis of Korean Sport for International Development Initiatives

A Sociocultural Analysis of Korean Sport for International Development Initiatives Dongkyu Na Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Kinetics School of Human Kinetics Faculty of Health Sciences University of Ottawa © Dongkyu Na, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Korean Sport for International Development ii Abstract This dissertation focuses on the following questions: 1) What is the structure of the Korean sport for international development discourse? 2) How are the historical transformations of particular rules of formation manifested in the discourse of Korean sport for international development? 3) What knowledge, ideas, and strategies make up Korean sport for international development? And 4) what are the ways in which these components interact with the institutional aspirations of the Korean government, directed by the official development assistance goals, the foreign policy and diplomatic agenda, and domestic politics? To address these research questions, I focus my analysis on the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) and its 30 years of expertise in designing and implementing sport and physical activity–related programs and aid projects. For this research project, I collected eight different sets of KOICA documents published from 1991 to 2017 as primary sources and two different sets of supplementary documents including government policy documents and newspaper articles. By using Foucault’s archaeology and genealogy as methodological -

NCKS News Fall 2014.Pdf

N A M C E N T E R FOR K O R E A N S T U D I E S University of Michigan 2014-2015 Newsletter Hallyu 2.0 volume Contemporary Korea: Perspectives on Minhwa at Michigan Exchange Conference Undergraduate Korean Studies INSIDE: 2 3 From the Director Korean Studies Dear Friends of the Nam Center: Undergraduate he notion of opportunity underlies the Nam Center’s programming. Studies Scholars (NEKST) will be held on May 8-9 of 2015. In its third year, TWhen brainstorming ideas, setting goals for an academic or cultural the 2015 NEKST conference will be a forum for scholarly exchange and net- Exchange program, and putting in place specific plans, it is perhaps the ultimate grati- working among Korean Studies graduate students. On May 21st of 2015, the fication that we expect what we do at the Nam Center to provide an op- Nam Center and its partner institutions in Asia will host the New Media and Conference portunity for new experiences, rewarding challenges, and exciting directions Citizenship in Asia conference, which will be the fourth of the conference that would otherwise not be possible. Peggy Burns, LSA Assistant Dean for series. The Nam Center’s regular colloquium lecture series this year features he Korean Studies Undergraduate Exchange Conference organized Advancement, has absolutely been a great partner in all we do at the Nam eminent scholars from diverse disciplines. jointly by the Nam Center and the Korean Studies Institute at the Center. The productive partnership with Peggy over the years has helped This year’s Nam Center Undergraduate Fellows program has signifi- T University of Southern California (USC) gives students who are interested open many doors for new opportunities. -

Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects by Daniel A

Sports, Culture, and Asia Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects By Daniel A. Métraux A 1927 photo of Kenichi Zenimura, the father of Japanese-American baseball, standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. Source: Japanese BallPlayers.com at http://tinyurl.com/zzydv3v. he essay that follows, with a primary focus on professional baseball, is intended as an in- troductory comparative overview of a game long played in the US and Japan. I hope it will provide readers with some context to learn more about a complex, evolving, and, most of all, Tfascinating topic, especially for lovers of baseball on both sides of the Pacific. Baseball, although seriously challenged by the popularity of other sports, has traditionally been considered America’s pastime and was for a long time the nation’s most popular sport. The game is an original American sport, but has sunk deep roots into other regions, including Latin America and East Asia. Baseball was introduced to Japan in the late nineteenth century and became the national sport there during the early post-World War II period. The game as it is played and organized in both countries, however, is considerably different. The basic rules are mostly the same, but cultural differences between Americans and Japanese are clearly reflected in how both nations approach their versions of baseball. Although players from both countries have flourished in both American and Japanese leagues, at times the cultural differences are substantial, and some attempts to bridge the gaps have ended in failure. Still, while doubtful the Japanese version has changed the American game, there is some evidence that the American version has exerted some changes in the Japanese game. -

Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society : Past, Present and Future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong Lee, Soon Nim, Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future, Doctor of Philosphy thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing - Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3051 This paper is posted at Research Online. Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society: Past, Present and Future Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong Soon Nim Lee Faculty of Creative Arts School of Journalism & Creative writing October 2009 i CERTIFICATION I, Soon Nim, Lee, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Creative Arts and Writings (School of Journalism), University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Soon Nim, Lee 18 March 2009. i Table of Contents Certification i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii Abstract viii Acknowledgements x Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Christianity awakens the sleeping Hangeul 12 Introduction 12 2.1 What is the Hangeul? 12 2.2 Praise of Hangeul by Christian missionaries -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Of the ROK with a Summary of the January 8-9 1986 Meeting Between the Two Korean NOCS

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified January 15, 1986 Letter from the International Olympic Committee President to the National Olympic Committee (NOC) of the ROK with a Summary of the January 8-9 1986 Meeting between the Two Korean NOCS Citation: “Letter from the International Olympic Committee President to the National Olympic Committee (NOC) of the ROK with a Summary of the January 8-9 1986 Meeting between the Two Korean NOCS,” January 15, 1986, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, International Olympic Committee Archives (Switzerland), SEOUL’ 88/ 2EME REUNION DES 2COREES 1985-86. Obtained for NKIDP by Sergey Radchenko. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113482 Summary: A letter from IOC President Samaranch to the North Korean Olympic Committee, which included a summary of a recent meeting between the Olympic Committees of North and South Korea, at which some of the issues discussed were events that could be held in North Korea, the torch relay, and future meetings. Original Language: English Contents: English Transcription Mr. Chong Ha KIM President Korean Olympic Committee C.P.O Box 1106 CONFIDENTIAL SEOUL / Korea Lausanne, 15th January 1986 Ref. No. /86/afb Re: Second meeting between the NOC of the Republic of Korea and the NOC of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Dear Mr. Kim, Further to the meeting held in Lausanne on 8th and 9th January 1986 between the NOCs of the Republic of Korea and of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, under the auspices of the International Olympic Committee, please find enclosed a resumé of the following discussions in which your delegation took part: - discussions between the IOC and the delegations from the NOCs of the Republic of Korea and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea; - discussions between the IOC and your delegation alone. -

Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste De Départ Détaillée

Yumenoshima Park Archery Field Archery 夢の島公園アーチェリー場 アーチェリー / Tir à l'arc Terrain de tir à l'arc du parc de Yumenoshima Men's Team 男子団体 / Épreuve par équipes - hommes MON 26 JUL 2021 Quarterfinal Start Time 13:45 準々決勝 / Quart de finale Extended Start List 拡張スタートリスト / Liste de départ détaillée Format In the team competition, the team shoots a series of matches, each match consisting of the best of 4 sets of 6 arrows (2 arrows per team member) in all rounds. After every set, the trailing team shoots first. In each set a team can score a maximum of 60 points. The team with the highest score of that set is awarded 2 points. In case of a tied score, both teams are awarded 1 point. As soon as a team reaches 5 set points (5 of 8 possible) it is declared winner and advances to the next round. The team has 120 seconds to shoot 6 arrows in alternate shooting format. In alternate shooting, the alternation between the teams will take place after all the team members have shot one arrow. The archers of the team are free to choose who shoots first and can change without restrictions as long as each team member shoots 1 arrow per alternation. If a match is tied at the end of 24 arrows, a sudden-death shoot-off will follow, with each team member shooting one arrow for score. The team has one minute to shoot the three arrows, and the team will alternate shots. If still tied, another three arrows are shot for score. -

Korean Reunification: the Dream and the Reality

KOREAN REUNIFICATION: THE DREAM AND THE REALITY CHARLES S. LEE Conventional wisdom, both Korean and non-Korean, assumis the division of this strategicpeninsula to be temporary. Officially, the Korean War still has not ended but is in a state of armistice. Popular belief also accepts as true that the greatest obstacles to Korean reunification are the East-West rivalry and the balance of power in the North Pacific. Charles S..Lee, however, argues that domestic conditions in North and South Korea actually present the more serious hurdle - a hurdle unlikely to be disposed of too quickly. INTRODUCTION Talk of reunifying the Korean peninsula once again is grabbing headlines. Catalyzed by the South Korean student movement's search for a new issue, the months surrounding the 1988 Summer Olympic Games in Seoul featured a flurry of unofficial and official initiatives on reunification. The students were quick to seize this emotionally charged issue as their new rallying cry, for the nation's recent democratic reforms (including a direct and seemingly fair presidential election in 1987) effectively deprived them of their raison d'etre. By June last year, thousands of them were on the march to the border village 6f Pahmunjom for a "summit" meeting with their North Korean counterparts. Not to be upstaged, the South Korean government blocked the marchers with tear gas, and on July 7, announced a sweeping set of proposals for improving North-South relations, including the opening of trade between the two Koreas. Capping last summer's events was South Korean President Roh Tae Woo's October speech at the UN General Assembly, in which he called for his own summit meeting with North Korean President Kim II Sung. -

Jurnal Pendidikan Jasmani Dan Olahraga

JPJO 5 (2) (2020) 218-232 Jurnal Pendidikan Jasmani dan Olahraga Available online at: https://ejournal.upi.edu/index.php/penjas/article/view/27256 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17509/jpjo.v5i2.27256 Indonesian Women’s Rowing from 1986 to 2018: A historical, Social and Cultural Perspective Dede Rohmat Nurjaya*, Amung Ma’mun, Agus Rusdiana Prodi Pendidikan Olahraga, Sekolah Pasca Sarjana, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Indonesia Article Info Abstract Article History : In 1954, the International Federation of Societes d'Aviron (FISA) organized the first Received June 2020 European women's rowing championship in Macon, France. Female rowing athletes Revised June 2020 around the world had actively participated for years, competing not only in local and national competitions, but also in international level. Apart from the historical evi- Accepted August 2020 dence that women could indeed compete at the international level, the FISA delegation Available online September 2020 found it more appropriate to limit women's international participation by shortening the distance of women's competitions to half of male athletes and limiting the number Keywords : and the type of race. Although women's international athletes were limited, the intro- Indonesia; Women Rowing; 1987-2018 duction of women's races at European championships created opportunities for female Era athletes to show their abilities to the public while challenging social and historical dis- course about Indonesian women's participation in rowing. Eversince this first race, female athletes and coaches had a desire to achieve gender equality in sports that are usually associated with men and masculinity. In 2003, their efforts culminated with the acceptance of women at European Championships, World Championships, and the Olympics, the change in the distance of women's rowing from 1,000 meters to 2,000 meters, and the introduction of women's lightweight class at World Championships and the Olympics.