Conflict Trends, Issue 3 (2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Statement by the Family of Lt General Maaparankoe Mahao on Sadc Report: 16 February 2016, Maseru, Lesotho

PRESS STATEMENT BY THE FAMILY OF LT GENERAL MAAPARANKOE MAHAO ON SADC REPORT: 16 FEBRUARY 2016, MASERU, LESOTHO Lt General Maaparankoe Mahao’s family has had the opportunity to study Justice Mphaphi Phumaphi Commission of Inquiry Report. As all of us will remember, the Commission was established by SADC to investigate the circumstances surrounding the death of General Mahao and the alleged mutiny against the current leadership of the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF). The Report was endorsed by the SADC Double Troika at its Summit held in Gaborone, Botswana on 18th January, 2016 with an injunction on the Lesotho Government to publish it and implement it. Lt General Mahao’s family once again wishes to express its gratitude to SADC for its efforts in the search for lasting peace and stability in the Kingdom of Lesotho and, in particular, to SADC’s unwavering commitment to get to the bottom of how and why Lt General Mahao was killed on 25th June, 2015. We further express our sincere appreciation of the thorough and professional work carried out by Justice Phumaphi’s Commission of Inquiry in the discharge of its mandate. We are fully aware of the very difficult conditions under which the Commission operated; especially the obstructions it encountered from some with vested interest to have the truth forever buried. Two principal objectives were at the heart of SADC’s decision to establish the Commission of Inquiry. These were the death of Lt General Mahao and the alleged mutiny within the ranks of the LDF. Around the death of Lt General Mahao, some significant progress was made in so far as the Commission ascertained certain facts which dispel and lay to rest the false claims made by the LDF with regards to why he was killed. -

Likoti, Injodemar 3

International Journal of Development and Management Review (INJODEMAR) Vol. 3 No. 1 May, 2008 215 THE CHALLENGES OF PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRACY IN LESOTHO: 1993-2007 LIKOTI, FAKO JOHNSON Department of Politics and Administrative Studies National University of Lesotho [email protected] Abstract Lesotho got its independence from Britain in 1960. The country experienced a coup in January 1970 while it was still fresh from colonial rule. During this period, the country's political parties were fragile and parliamentarians (MPs) were yet to acclimatise themselves with their parliamentary responsibilities. From 1970-1992, the country did not have a democratically elected parliament. It was not until early 1993 that the dawn of democracy came to Lesotho. This meant that MPs were still inexperienced and the National parliament appeared to have been confronted with myriads of challenges. This paper argues that these challenges have not only undermined the parliament but have also impacted negatively on the legitimacy and accountability of parliament. It further opines that parliamentarians in any democracy are held in high regard by the electorate and have to conduct themselves with due diligence. As MPs, they are expected to conduct themselves in parliament in a manner befitting their public status. Key Words: Democratisation, Unparliamentary practices, Opposition parties, Legislative power, Lesotho. Introduction Lesotho is a Constitutional democracy. This means that the country subscribes to constitutional rule. The concept of constitutionalism limits the arbitrariness of political power. While the concept recognises the necessity of government, it also insists upon limitations placed upon its powers. In essence, constitutionalism is an antithesis of arbitrary rule. -

The Impact of Political Parties and Party Politics On

EXPLORING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND PARTY SYSTEMS ON DEMOCRACY IN LESOTHO by MPHO RAKHARE Student number: 2009083300 Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the Magister Degree in Governance and Political Transformation in the Programme of Governance and Political Transformation at the University of Free State Bloemfontein February 2019 Supervisor: Dr Tania Coetzee TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations and acronyms ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 1 ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction to research ....................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Motivation ........................................................................................................................................ 9 1.2 Problem statement ..................................................................................................................... -

Lesotho | Freedom House

Lesotho | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/lesotho A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 10 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 3 / 4 Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy. King Letsie III serves as the ceremonial head of state. The prime minister is head of government; the head of the majority party or coalition automatically becomes prime minister following elections, making the prime minister’s legitimacy largely dependent on the conduct of the polls. Thomas Thabane became prime minister after his All Basotho Convention (ABC) won snap elections in 2017. Thabane, a fixture in the country’s politics, had previously served as prime minister from 2012–14, but spent two years in exile in South Africa amid instability that followed a failed 2014 coup. A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 The lower house of Parliament, the National Assembly, has 120 seats; 80 are filled through first-past-the-post constituency votes, and the remaining 40 through proportional representation. The Senate—the upper house of Parliament—consists of 22 principal chiefs who wield considerable authority in rural areas and whose membership is hereditary, along with 11 other members appointed by the king and acting on the advice of the Council of State. Members of both chambers serve five- year terms. In 2017, the coalition government of Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili—head of the Democratic Congress (DC)—lost a no-confidence vote. The development triggered the third round of legislative elections held since 2012. -

ASPJ-Africa & Francophonie 3Rd Quarter 2017

ASPJ–Afrique etFrancophonie3 3e trimestre 2017 Volume 8, No. 3 e Trimestre 2017 Trimestre La vision américaine du monde post-impérial Michael Lind Faith I. Okpotor, PhD Okpotor, I. Faith A Feminist Normative Analysis of the Libyan Intervention Libyan the of Analysis Normative Feminist A Politics, and US Foreign Policy Foreign US and Politics, Maîtriser la guerre dite « hybride » Human Rights, Humanitarian Intervention, International Intervention, Humanitarian Rights, Human LTC Jyri Raitasalo, Armée finlandaise, PhD Everisto Benyera, PhD Benyera, Everisto Le modèle des systèmes de corruption et réforme anticorruption in Lesotho in La pression internationale et nationale, et stratégies des gouvernements Towards an Explanation of the Recurrence of Military Coups Coups Military of Recurrence the of Explanation an Towards pour préserver le statu quo Joseph Pozsgai, PhD Joseph Pozsgai, PhD Pozsgai, Joseph Preserve the Status Quo Status the Preserve Tentative d’explication des coups d’état à répétition au Lesotho International, Domestic Pressure, and Government Strategies to to Strategies Government and Pressure, Domestic International, Everisto Benyera, PhD A Systems Model on Corruption and Anticorruption Reform Anticorruption and Corruption on Model Systems A Droits de l’homme, intervention humanitaire, politique Lt Col Jyri Raitasalo, Finnish Army, PhD Army, Finnish Raitasalo, Jyri Col Lt internationale et politique étrangère américaine Getting a Grip on the So-Called “Hybrid Warfare” “Hybrid So-Called the on Grip a Getting Une analyse normative féministe de l’intervention en Libye Faith I. Okpotor, PhD Michael Lind Michael American Visions of a Postimperial World Postimperial a of Visions American Volume 8, No. 3 No. 8, Volume 2017 Quarter 3rd ASPJ–Africa and Francophonie 3rd Quarter 2017 Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen David L. -

Implications for Consolidation of Democracy in Lesotho by Libuseng Malephane

Contesting and turning over power: Implications for consolidation of democracy in Lesotho By Libuseng Malephane Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 17 | February 2015 Introduction Since its transition to electoral democracy in 1993, Lesotho has experienced a series of upheavals related to the electoral process. Election results were vehemently contested in 1998, when the ruling Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) won all but one of the country’s constituencies under a first-past-the-post electoral system, and a military intervention by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) was required to restore order. A mixed member proportional (MMP) model introduced in the run-up to the 2002 general elections resulted in more parties being represented in Parliament. The MMP model also led to the formation of informal coalitions as political parties endeavoured to maintain or increase their seats in Parliament in the 2007 elections (Kapa, 2007). Using a two-ballot system, with one ballot for constituency and another for the proportional-representation (PR) component, the elections preserved the ruling LCD’s large majority in Parliament and precipitated another protracted dispute between the ruling and opposition parties over the allocation of PR seats. Mediation efforts by the SADC and the Christian Council of Lesotho led to a review of the Constitution and Electoral Law. The resulting National Assembly Electoral Act of 2011 provides for a single-ballot system that allows voters to indicate their preferences for both constituency and PR components of the MMP system (UNDP, 2013). Meanwhile, the new All Basotho Convention (ABC), which had broken away from the LCD in 2006, became the largest opposition party in Parliament after the 2007 elections. -

FOL Newsletter 3QTR

Metsoalle ea Lesotho Friends of Lesotho Third Quarter 2014 Newsletter Newsletter Features Clickable Links!! Download the newsletter from the FOL FOL President Appointed website www.friendsoflesotho.org and you will be able to click on all the Honorary Consul website addresses. Friends of Lesotho President Scott Rosenberg was appointed Honorary Consul by the Lesotho Embassy in Washington, DC. He will represent Lesotho in Ohio and the Midwest and help facilitate greater cooperation between the two countries to promote Lesotho’s trade, tourism, investment, and cultural activities to Ameri- cans, and he will also assume protocol responsibilities for visiting Basotho dignitaries. The current Ambassador to the US, serving in the Washington DC consulate, is Ambassador Molapi Sepetane. Scott Rosenberg (R) with Lesotho Minister of Protocol Moshuli Leteka, Summer 2014, Maseru. Photo Credit: Thabo Moseunyane Was There a Coup or Not? By Ella Kwisnek, RPCV 92-94, Lesotho Agricultural College, [email protected] A quarterly newsletter is not an ideal place for fast-breaking news, so thanks to RPCV Ella Kwis- nek for compiling this log of events that made front pages on world newspapers during August and Sept 2014. ~ Ed. What happened? On Saturday, August 30, 2014, there was a reported “coup d'état attempt by the military” in Lesotho. Soldiers reportedly disarmed police and one police officer was killed as the result of an ex- change of gunfire between soldiers and police. Prime Minister Motsoahae Thomas Thabane fled to South Africa and accused his deputy Mothetjoa Metsing Photo Credit: Linda Henry, RPCV of being behind the army's actions. Foreign Ministers of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) States met with the leaders of the three political parties that made up Lesotho’s Coalition govern- ment in an attempt to resolve the conflict. -

Alliances, Coalitions and the Political System in Lesotho 2007-2012

VOLUME 13 NO 1 93 ALLIANCES, COALITIONS AND THE POLITICAL SYSTEM IN LESOTHO 2007-2012 Motlamelle Anthony Kapa and Victor Shale Dr Motlamelle Anthony Kapa is lecturer and head of the Department of Political and Administrative Studies at the National University of Lesotho e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Dr Victor Shale is EISA’s Zimbabwe Resident Director e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper assesses political party alliances and coalitions in Lesotho, focusing on their causes and their consequences for party systems, democratic consolidation, national cohesion and state governability. We agree with Kapa (2008) that formation of the pre-2007 alliances can be explained in terms of office-seeking theory in that the political elite used alliances to access and retain power. These alliances altered the country’s party system, leading to conflict between parties inside and outside Parliament, as well as effectively changing the mixed member proportional (MMP) electoral system into a parallel one, thereby violating the spirit of the system. However, the phenomenon did not change state governability; it effectively perpetuated the one-party dominance of the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) and threatened national cohesion. The post-2012 coalition, on the other hand, was a product of a hung parliament produced by the elections. The impact of the coalition on the party system, state governability and democratic consolidation is yet to be determined as the coalition phenomenon is still new. However, state governability has been marked by a generally very slow pace of policy implementation and the party system has been both polarised and reconfigured while national cohesion has been strengthened. -

Doctoral Dissertation

Doctoral Dissertation A Critical Assessment of Conflict Transformation Capacity in the Southern African Development Community (SADC): Deepening the Search for a Self-Sustainable and Effective Regional Infrastructure for Peace (RI4P) MALEBANG GABRIEL GOSIAME G. Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation Hiroshima University September 2014 A Critical Assessment of Conflict Transformation Capacity in the Southern African Development Community (SADC): Deepening the Search for a Self-Sustainable and Effective Regional Infrastructure for Peace (RI4P) D115734 MALEBANG GABRIEL GOSIAME G. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation of Hiroshima University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2014 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this doctoral thesis is in its original form. The ideas expressed and the research findings recorded in this doctoral thesis are my own unaided work written by me MALEBANG GABRIEL GOSIAME G. The information contained herein is adequately referenced. It was gathered from primary and secondary sources which include elite interviews, personal interviews, archival and scholarly materials, technical reports by both local and international agencies and governments. The research was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards and guidelines of the Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation (IDEC) of Hiroshima University, Japan. The consent of all respondents was obtained using the consent form as shown in Appendix 3 for the field research component of the study and for use of the respondent’s direct words as quoted therein. iii DEDICATIONS This dissertation is dedicated to the loving memory of my mother Roseline Keitumetse Malebang (1948 – 1999) and to all the people of Southern Africa. -

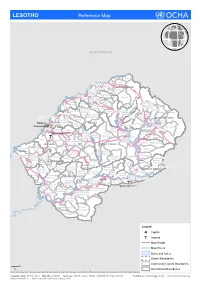

LESOTHO Reference Map

LESOTHO Reference Map SOUTH AFRICA Makhunoane Liqobong Likila Ntelle n Maisa-Phoka Ts'a-le- o d Moleka le BUTHA BUTHE a Lipelaneng C Nqechane/ Moteng Sephokong Linakeng Maputsoe Leribe Menkhoaneng Sekhobe Litjotjela Likhotola/ LERIBE Hleoheng Malaoaneng Manka/ Likhakeng Matlameng Mapholaneng/ Fobane Koeneng/ Phuthiatsana Kolojane Lipetu/ Kao Pae-la-itlhatsoa -Leribe Fenyane Litsilo -Pae-la-itlhatsoa Mokhachane/ Mamathe/Bulara Mphorosane Molika-liko Makhoroana Limamarela Tlhakanyu/Motsitseng Teyateyaneng Seshote Mapholaneng/ Majoe-Matso/ Meno/ Lekokoaneng/Maqhaka Mohatlane/ Sebetia/Khokhoba Pae-la-itlhatsoa Matsoku -Mapholaneng MOKHOTLONG Lipohong Thuapa-Kubu/ Moremoholo/ Katse Popa Senekane BEREA Moshemong Maseru Thuathe Koali/ Taung/Khubelu Mejametalana p Mokhameleli Semenanyane Mokhotlong S Maluba-lube/ Mateanong e Maseru Suoane/ m Rafolatsane Thaba-Bosiu g Ratau e Liphakoeng n Bokong n e a Ihlo-Letso/ Mazenod Maseru Moshoeshoe l Setibing/ Khotso-Ntso Sehong-hong e Tsoelike/ Moeketsane h Pontseng/ Makopoi/ k Mantsonyane Bobete p Popa_MSU a Likalaneng Mahlong Linakaneng M Thaba-Tseka/ Rothe Mofoka Nyakosoba/Makhaleng Maboloka Linakeng/Bokhoasa/Manamaneng THABA TSEKA Kolo/ MASERU Setleketseng/ Tebang/ Matsieng Tsakholo/Mapotu Seroeneg S Mashai e Boleka n Tsa-Kholo Ramabanta/ q Methalaneng/ Tajane Moeaneng u Rapo-le-boea n Khutlo-se-metsi Litsoeneng/Qalabane Maboloka/ y Sehonghong Thaba-Tsoeu/ Monyake a Lesobeng/ Mohlanapeng Mathebe/ n Sehlaba-thebe/ Thabaneng Ribaneng e Takalatsa Likhoele Moshebi/ Kokome/ MAFETENG Semonkong Leseling/ -

National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho Final Report

The Government of Lesotho National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho Final Report October 2007 The Government of Lesotho National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho Final Report October 2007 Report no. 64131-0-13 Issue no. 3.2 Date of issue 20 October 2007 Prepared NBP Checked DH/ABR/CW/GB Approved NBP National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho - Final Report 1 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Electrification Target 6 1.3 Settlements 7 1.4 Load Forecast 8 1.5 Technical Standards 9 1.6 Systems in Remote Areas 10 1.7 Transmission System 11 1.8 Distribution Systems 11 1.9 Financial Aspects 13 1.10 Prioritisation of Settlements 14 1.11 Project Schedule Years 1 to 5 - Distribution 15 1.12 Project Schedule for Years 6 - 15 - Distribution 18 1.13 Allocation of Responsibilities 19 1.14 Future Service Models for Electricity Supply 21 1.15 Tariffs and Connection Fee 21 1.16 Subsidies 22 1.17 Institutional Development and Training 23 1.18 Monitoring and Evaluation Framework 23 1.19 Environmental Issues 25 2 Introduction 27 2.1 Electrification Target for Lesotho 27 2.2 Balancing Policy Objectives 28 2.3 Planning Criteria and Approach 29 2.4 Report Structure and Terminology 32 3 Background 34 3.1 Context 34 3.2 Energy Policy and Power Sector Reform 35 3.3 Institutions Involved in Electrification 37 3.4 Existing Power System 42 P:\64131A\3_Pdoc\DOC\Final Report\færdige\Final Report October 2007\Final Report\Final Report-october.doc . -

Un Royaume En Eaux Troubles : Les Crises Politico-Sécuritaires Du Lesotho

AVRIL 2021 Un royaume en eaux troubles Les crises politico-sécuritaires Centre Afrique oubliées du Lesotho subsaharienne Thibaud KURTZ L’Ifri est, en France, le principal centre indépendant de recherche, d’information et de débat sur les grandes questions internationales. Créé en 1979 par Thierry de Montbrial, l’Ifri est une association reconnue d’utilité publique (loi de 1901). Il n’est soumis à aucune tutelle administrative, définit librement ses activités et publie régulièrement ses travaux. L’Ifri associe, au travers de ses études et de ses débats, dans une démarche interdisciplinaire, décideurs politiques et experts à l’échelle internationale. Les opinions exprimées dans ce texte n’engagent que la responsabilité de l’auteur. ISBN : 979-10-373-0348-6 © Tous droits réservés, Ifri, 2021 Couverture : © Shutterstock/South Africa Stock Video », Barrage de Katse au Lesotho Comment citer cette publication : Thibaud Kurtz, « Un royaume en eaux troubles : les crises politico- sécuritaires oubliées du Lesotho », Notes de l’Ifri, Ifri, avril 2021. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 E-mail : [email protected] Site internet : Ifri.org Auteur Thibaud Kurtz est analyste en géopolitique africaine. Il a mené de nombreuses missions pour des réseaux d’ONG et diplomatiques européens en Afrique australe et des Grands Lacs. Après avoir travaillé au sein d’EurAc à Bruxelles, il a été basé au Botswana pendant plusieurs années, où il a occupé des postes régionaux pour les missions diplomatiques de la France, de l’Union européenne et du Royaume-Uni.