The Domestic Paradox1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Phillips Presents Nordic Impressions

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts: June 7, 2018 Hayley Barton, 202.387.2151 x235 [email protected] Miriam Magdieli, 202.387.2151 x240 [email protected] Online Press Room: www.phillipscollection.org/press THE PHILLIPS PRESENTS NORDIC IMPRESSIONS Art from Åland, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, 1821-2018 WASHINGTON—A major survey of nearly 200 years of Nordic art, featuring many works never seen before in the U.S., will be presented by The Phillips Collection this fall. The exhibition, Nordic Impressions: Art from Åland, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, 1821-2018, includes 52 works by as many artists, spanning paintings to video installations. The exhibition will be on view October 13, 2018 through January 13, 2019. Nordic Impressions pays tribute to the artistic excellence of 19th- and 20th-century Nordic painters, such as Edvard Munch, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Vilhelm Hammershøi, Anders Zorn, and Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval. Celebrating the considerable artistic diversity in Nordic art, the broad spectrum of works feature both the expected (sublime landscapes and melancholic portraits) and the unexpected (abstract and conceptual art). Prominent contemporary artists include Katrín Sigurdardóttir, Ragnar Kjartansson, and Olafur Eliasson from Iceland; Israeli-born Danish painter Tal R; Norwegian performance and video artist Tori Wrånes; Swedish artist Nathalie Djurberg; and Sámi artists Outi Pieski and Britta Marakatt-Labba. “We are thrilled to showcase the art of the Nordic countries. It has been very satisfying to have worked over the past few years with the embassies that are our neighbors here in Washington, DC and with our many colleagues who have such rich expertise,” said Phillips Director Dorothy Kosinski. -

Höstprogram 2013 Omslagets Insida

HÖSTPROGRAM 2013 omslagets insida Medlemskap i Föreningen Senior universitetet i Stockholm Medlem i föreningen kan du bli om du är pen När du deltar i Senioruniversitetets arrangemang sionär och har fyllt 55 år. För att delta i Senior åtnjuter du viss försäkring vid olycksfall genom universitetets arrangemang krävs medlemskap Folkuniversitetet. i föreningen. För år 2013 är medlemsavgiften 150 kronor. Beträffande inbetalning se vad som sägs nedan under punkt 2. Anmälan och inbetalning av avgifterna Anmälan till arrangemang görs antingen på bifogade anmälningskort i kurskatalogen fr o m den 13 augusti (v g texta!) eller via vår webbplats www. senioruniversitetet.se, som öppnas den 14 augusti. Observera att anmälan inte kan göras via epost. För att underlätta kansliets hantering får varje Fr o m 2008 kräver Folkbildningsrådet att anmälan bara gälla en person för varje arrange person nummer registreras på deltagare som mang. Sökande bereds plats i den ordning de deltar i folkbildningsverksamhet. Ange därför anmält sig. tydligt vid anmälan och inbetalning namn, person nummer, adress, telefonnummer och Observera att inbetalningen av avgifter för epostadress. Om du angivit din epostadress höstterminen går till på följande sätt: sänds kallelse, faktura och andra meddelanden till den, ej till postadressen. 1. Alla som sökt till arrangemang får besked om de kommer med på arrangemanget eller inte. Anmälan till arrangemang är bindande. Om du återtar anmälan senare än en vecka före 2. Om du kommit med på ett arrangemang och kursstart betalar du 100 kronor i expeditions ännu inte är medlem får du faktura på såväl avgift, efter kursstart full avgift. medlemsavgiften som avgiften för arrange manget. -

Uppsatser I Konstvetenskap Läsåret 2013/2014

UPPSATSER I KONSTVETENSKAP LÄSÅRET 2013/2014 01. Kjellberg, Sophia: Återlämnande av kulturföremål – En analys av Sveriges argumentation kring repatriering och återlämning av föremål av kulturellt värde angående ärendet hövding G‘psgoloxs totempåle från Etnografiska museet. (Kand) 02. Wilson, Torbjörn: Normbrytande performativ i Barock och samtid – En komparativ analys av Artemisia Gentileschis Judit halshugger Holofernes och Sigalit Landaus Barbed Hula. (Kand) 03. Calmfors, Helena: STREETSTYLE-BILDER I ETT NYTT MEDIUM. En kvalitativ undersökning av streetstyle-bloggarna The Sartorialist och JAK&JIL. (Kand) 04. Dahlström, Sara: BECOMING CLEAN. En studie av David LaChapelles porträttserie. (Kand) 05. Kalén, Isabella: Att appropriera det förflutna – antika referenser i samtidskonsten. (Kand) 06. Appelsved, Emelie: Prada Marfa. Om platsspecificitet, politik och höjda ögonbryn i Texas öken. (Kand) 07. Sipilä, Varpu: Why Surrealism? – A study of advertisements inspired by the styles of Salvador Dalí and René Magritte. (Kand) 08. Eriksson, Johanna: Förnyelsen av ett flerbostadshus från miljonprogrammet – en komparativ undersökning av nu och då. (Kand) 09. Granberg, Maja: Relationen mellan plats och arkitektur. En fenomenologisk analys. (Kand) 10. Jarl, Elena: Afrikanska eller Västerländska Mästerverk? En narrativ och postkolonial undersökning av utställningskonceptet i Världskulturmuseernas utställning Afrikanska mästerverk, Stockholm, 2013– 2014. (Kand) 11. Ekdahl, Ingemar: En formvärld i fothöjd – om hörnblad i svenska medeltidskyrkor. (Kand) 12. Mattsson, Klara: Alphonse Mucha och Sarah Bernhardt. En semiotisk analys av Muchas reklamaffischer för ’Théâtre de la Renaissance’. (Kand) 13. Sallnäs, Kristina: Myterna bakom höga marknadspriser för konst. (Kand) 14. Mårland, Charlotte: PROVRUM – en privat sfär i det offentliga rummet. (Kand) 15. Lindström, Eva: Konst i statens rum. Om konsten i tre länsresidens. (Kand) 16. -

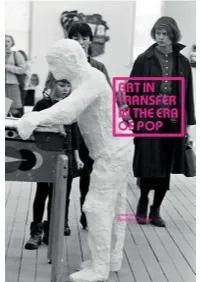

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

En Bortglömd Värld Av Blommor. Märta Rudbecks Konstnärskap Under Tidigt 1900-Tal English Title: a Forgotten World of Flowers

En bortglömd värld av blommor Märta Rudbecks konstnärskap under tidigt 1900-tal Matilda Eliasson Masteruppsats i konstvetenskap, 45 hp Uppsala universitet, ht 2020 Handledare: Britt-Inger Johansson Abstract Master’s Thesis, 45 credits Title: En bortglömd värld av blommor. Märta Rudbecks konstnärskap under tidigt 1900-tal English Title: A Forgotten World of Flowers. The Artistry of Märta Rudbeck in the Early 1900’s Author: Matilda Eliasson Supervisor: Britt-Inger Johansson Examiner: Carina Jacobsson Department of Art History Uppsala University This thesis rediscovers the Swedish painter Märta Rudbeck (1882–1933). During her lifetime she was an esteemed composer of flower still lifes and portraits. Her forgotten heritage follows those of other female artists, whose legacies are long forgotten. By retracing her life through archives and newspaper articles, a picture of her upbringing, education, career and network affiliations emerges. By using the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieus field theory, the aim of the thesis is to analyse the social, educational, cultural and economic aspects that affected Märta Rudbeck’s life, and how this was manifested in her art. The strategies Märta Rudbeck encompassed, are highlighted in the analysis. She chose to exhibit her work with a variety of associations and also took commissions for portraits and copies of older works of art. The analysis also reveals how she followed in her mother’s footsteps and embraced female networks to further her career. Furthermore, the thesis uncovers how her heritage, social class and upbringing most likely influenced her choice of genre, which in turn has prevented her from staying relevant since her untimely death in the early 1930’s. -

Lopulliset Hinnat Important Winter Sale 613

Lopulliset hinnat Important Winter Sale 613 Nro Esine Vasarahinta 1 A Swedish late Baroque cabinet by Johan Hugo Fürloh (master in Stockholm 1724- 48 000 SEK 1745). 2 A Swedish Rococo 18th century cabinet. 40 000 SEK 3 A Baroque late 17th century cabinet. 24 000 SEK 4 A pair of Louis XV 18th century corner cupboards by Léonard Boudin (1735-1804), 80 000 SEK master in Paris 1761. 5 A Swedish late Baroque 1720-40's writing desk. 70 000 SEK 6 A French Baroque Bureau Mazarin desk, circa 1700, circle of Nicolas Sageot (1666-1731). 175 000 SEK 7 A Swedish Rococo 18th century writing table. 30 000 SEK 8 A Gustavian late 18th century secretaire attributed to Jonas Hultsten (master in 32 000 SEK Stockholm 1773-1794). 9 A Swedish Royal Rococo mid 18th century table, belonged to Lovisa Ulrika (Queen of 140 000 SEK Sweden 1751-1771). 10 A Gustavian late 18th century console table. 30 000 SEK 11 A Gustavian late 18th century console table. 95 000 SEK 12 A Gustavian late 18th century console table. 55 000 SEK 13 A Gustavian late 18th century console table. 20 000 SEK 14 A Gustavian late 18th century console table. 34 000 SEK 15 A late Gustavian early 19th century console table. 34 000 SEK 16 A late Gustavian circa 1800 console table. 32 000 SEK 17 A late Gustavian early 19th century console table. 20 000 SEK 18 A late Gustavian late 18th century console table. 50 000 SEK 19 A Swedish Empire 1820/30's console table. -

Lopulliset Hinnat Important Winter Sale 629

Lopulliset hinnat Important Winter Sale 629 Nro Esine Vasarahinta 1 A Swedish late Baroque 18th century cupboard. 45 000 SEK 2 A Swedish late Baroque 18th century cupboard. 35 000 SEK 3 A Swedish cupboard from region of Dalarna 18th Century. 65 000 SEK 4 A Swedish cabinet from the late 17th century. Ei myyty 5 A Swedish Empire bookcabinet. 65 000 SEK 6 A Swedish late Baroque commode by Johan Hugo Fürloh (master in Stockholm 1724- 12 000 SEK 1745). 7 A Swedish Rococo 18th century commode by Christian Linning, master 1744. 70 000 SEK 8 A Swedish Rococo 18th century commode attributed to N. Korp. Ei myyty 9 A Swedish Rococo 18th century commode by J Gröndahl. 30 000 SEK 10 A Swedish Rococo 18th century commode by J Noraeus, master 1769-1781. 30 000 SEK 11 A Swedish Rococo 18th century commode. 24 000 SEK 12 A Swedish Rococo commode by J Noraeus. 33 000 SEK 13 A Gustavian late 18th century commode attributed to J. Hultsten. 85 000 SEK 14 A Gustavian commode attributed to J. Hultsten. 70 000 SEK 15 A Gustavian late 18th century commode attributed to J. Hultsten. 100 000 SEK 16 A Gustavian late 18th century commode by C. Lindborg. 30 000 SEK 17 A Gustavian late 18th century commode by Johan Neijber (not signed), master 1768. 110 000 SEK 18 A late Gustavian commode, late 18th century. Ei myyty 19 A late Gustavian commode. 60 000 SEK 20 A late Gustavian circa 1800 commode. 17 000 SEK 21 A Swedish late Gustavian commode, from Nils Asplind's workshop in Falun, active 1785- 95 000 SEK 1820. -

Förändra Eller Bevara

1(11) Förändra eller bevara Carl Larsson (1853–1919) Friluftsmålaren. Vintermotiv från Åsögatan 145, Stockholm Open-Air Painter. Winter-Motif from Åsögatan 145, Stockholm NM 2546 Eugène Jansson (1862–1915) Riddarfjärden, Stockholm NM 1699 Axel Lindman (1848–1930) Inloppet till Stockholm Sea Approach to Stockholm NM 1370 Acke (eg. Johan Axel Gustaf Andersson), J.A.G. (1859–1924) Midsommarfest i metallstaden Midsummer Celebration in the Metal City NM 6735 Nils Kreuger (1858–1930) Marsafton March Evening NM 1555 Jean-Maxime Claude (1824–1904) Tre ryttare vid havet Three Riders at the Sea NM 1596 2(11) Okänd (1600/1699) Skelettskogen The Skeleton Forest NM 4668 Eugène Jansson (1862–1915) Stadens utkant The Outskirts of the Town NM 2134 Gustaf Wilhelm Palm (1810–1890) Utsikt över Riddarholmskanalen i Stockholm 1835 View of the Riddarholmskanalen, Stockholm, 1835 NM 1414 Kontroversiellt eller korrekt? Mathys Ignatius van Bree (1773–1839) Förnäm familj ger allmosa i en park A Noble Family Distributing Alms in a Park NM 361 Bernardo Cavallino (1622–1654) Judit med Holofernes huvud Judith with the head of Holofernes NM 80 Hildegard Thorell (1850–1930) Modersglädje. Konstnären Jacob Kulles maka Maternal Joy. The Wife of the Artist Jacob Kulle NM 1471 3(11) Gustaf Cederström (1845–1933) Epilog Epilogue NM 1296 Jan Massys (1509–1575) Det omaka paret The Ill-matched Couple NM 508 Lucas Cranach d.ä. (1472–1553) Lucretia NM 1080 Georg Engelhard Schröder (1684–1750) Juno eller Allegori över elementet Luften Juno or Allegory of the Element Air NM 1014 -

Results Autumn Classic Sale

Results Autumn Classic Sale, No. Item Hammer price 1 Nils Kreuger, "Utanför barriären", motiv från Paris (Outside the barrier, scene from Paris). 36 000 SEK 2 Julia Beck, "Fin d'Octobre, Vaucresson". 90 000 SEK 3 Julia Beck, River landscape, Grez-sur-Loing. 140 000 SEK 4 Helmer Osslund, Lake Kallsjön, Jämtland. 230 000 SEK 5 Helmer Osslund, "Vårvinterdag med nysnö, Forsmo" (Early spring with newly fallen 130 000 SEK snow, landscape from Forsmo). 6 Helmer Osslund, Spring landscape. 50 000 SEK 7 Anton Genberg, "Bodsjöedet". 21 000 SEK 8 Carl Johansson, Summer landscape from Åre. 22 000 SEK 9 Carl Johansson, Harbour scene from Härnösand. 12 000 SEK 10 Helmer Osslund, Northern landscape in autumn. Unsold 11 Helmer Osslund, "Höstdag, Fränsta" (Autumn Day, Fränsta). 175 000 SEK 12 Helmer Osslund, River landscape, Ångermanland. 60 000 SEK 13 Robert Thegerström, Reflecting pond. 5 000 SEK 14 Karl Nordström, "Borreberget, Tjörn". 70 000 SEK 15 Bruno Liljefors, Gustaf Kolthoff hunting. 42 000 SEK 16 Fanny Brate, Teasing children. 165 000 SEK 17 Prins Eugen, "Det klarnar" (Skies clear, scene from Tyresö). 150 000 SEK 18 Olle Hjortzberg, Still life with yellow roses and chinese porcelain. 50 000 SEK 19 Olle Hjortzberg, Meadow flowers in silver Beaker. 95 000 SEK 20 Olle Hjortzberg, Roses in a silver vase. 75 000 SEK 20A Prins Eugen, "Båthamnen, Waldemarsudde" (The boat harbour, Waldemarsudde). 55 000 SEK 21 Bruno Liljefors, Two sea eagles and an eider duck. 620 000 SEK 22 Bruno Liljefors, Hunter with hounds and fox. 250 000 SEK 23 Bruno Liljefors, Winter landscape with hare. -

Becoming Artists: Self-Portraits, Friendship Images and Studio Scenes by Nordic Women Painters in the 1880S (Diss

Carina Rech, Becoming Artists: Self-Portraits, Friendship Images and Studio Scenes by Nordic Women Painters in the 1880s (diss. Stockholm 2021) Edition to be published electronically for research, educational and library needs and not for commercial purposes. Published by permission from Makadam Publishers. A printed version is available through book stores: ISBN 978-91-7061-354-8 Makadam Publishers, Göteborg & Stockholm, Sweden Upplaga för elektronisk publicering för forsknings-, utbildnings- och biblioteksverksamhet och ej för kommersiella ändamål. Publicerad med tillstånd från Makadam förlag. Tryckt utgåva finns i bokhandeln: ISBN 978-91-7061-354-8 Makadam förlag, Göteborg & Stockholm www.makadambok.se becoming artists CARINA RECH Becoming Artists Self-Portraits, Friendship Images and Studio Scenes by Nordic Women Painters in the 1880s makadam makadam förlag göteborg · stockholm www.makadambok.se This book is published with grants from Gunvor och Josef Anérs stiftelse Gerda Boëthius’ minnesfond Stiftelsen Konung Gustaf VI Adolfs fond för svensk kultur Kungl. Patriotiska sällskapet Torsten Söderbergs stiftelse Berit Wallenbergs stiftelse Åke Wibergs stiftelse Becoming Artists: Self-Portraits, Friendship Images and Studio Scenes by Nordic Women Painters in the 1880s Academic dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History at Stockholm University, to be publicly defended on Friday 4 June 2021 © Carina Rech 2021 Cover image: Bertha Wegmann, The Artist Jeanna Bauck, 1881, detail of fig. 60. Photo: Nationalmuseum. © for illustrations, see list of figures on p. 436 isbn 978-91-7061-854-3 (pdf) table of contents Acknowledgments 7 Introduction 11 Aim and Research Questions 13 Artists, Locations and Social Fabric 15 Material 21 The 1880s in Nordic Art – Professionalization, Mobility and Transnational Encounters 28 Theories and Methods 34 Previous Research 54 Outline 62 I. -

Neither Reform Nor Rescue: “Woman’S Work,” Ordinary Culture, and the Articulation of Modern Swedish Femininities

JoAnn Conrad 2021: Neither Reform nor Rescue: “Woman’s Work,” Ordinary Culture, and the Articulation of Modern Swedish Femininities. Ethnologia Europaea 51(1): 99–136. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/ee.1896 Neither Reform Nor Rescue “Woman’s Work,” Ordinary Culture, and the Articulation of Modern Swedish Femininities JoAnn Conrad, Diablo Valley College, Pleasant Hill, California, United States, [email protected] This article examines the role of women in the construction of modern Swedish subjectivity through their participation in both quotidian activities and their networks of relations. Taking the work of Barbro Klein as a point of departure, I argue that Swedish women of the fin de siècle worked within overlapping and interconnected women’s networks through which they fashioned their own responses to the pressures of modernity within particular configurations of gender. Combining the social and political, formal and informal, labor and leisure, they created spaces for alternate cultural, commercial and social responses. These spaces from which femininity was lived as a positionality in discourse and social practice challenge the false dichotomies of past–future and tradition–modernity which have been central to the disciplinary narrative of folklore studies. Ethnologia Europaea is a peer-reviewed open access journal published by the Open Library of Humanities. © 2021 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. -

Lopulliset Hinnat Autumn Classic Sale

Lopulliset hinnat Autumn Classic Sale, Nro Esine Vasarahinta 1 Nils Kreuger, "Utanför barriären", motiv från Paris (Outside the barrier, scene from Paris). 36 000 SEK 2 Julia Beck, "Fin d'Octobre, Vaucresson". 90 000 SEK 3 Julia Beck, River landscape, Grez-sur-Loing. 140 000 SEK 4 Helmer Osslund, Lake Kallsjön, Jämtland. 230 000 SEK 5 Helmer Osslund, "Vårvinterdag med nysnö, Forsmo" (Early spring with newly fallen 130 000 SEK snow, landscape from Forsmo). 6 Helmer Osslund, Spring landscape. 50 000 SEK 7 Anton Genberg, "Bodsjöedet". 21 000 SEK 8 Carl Johansson, Summer landscape from Åre. 22 000 SEK 9 Carl Johansson, Harbour scene from Härnösand. 12 000 SEK 10 Helmer Osslund, Northern landscape in autumn. Ei myyty 11 Helmer Osslund, "Höstdag, Fränsta" (Autumn Day, Fränsta). 175 000 SEK 12 Helmer Osslund, River landscape, Ångermanland. 60 000 SEK 13 Robert Thegerström, Reflecting pond. 5 000 SEK 14 Karl Nordström, "Borreberget, Tjörn". 70 000 SEK 15 Bruno Liljefors, Gustaf Kolthoff hunting. 42 000 SEK 16 Fanny Brate, Teasing children. 165 000 SEK 17 Prins Eugen, "Det klarnar" (Skies clear, scene from Tyresö). 150 000 SEK 18 Olle Hjortzberg, Still life with yellow roses and chinese porcelain. 50 000 SEK 19 Olle Hjortzberg, Meadow flowers in silver Beaker. 95 000 SEK 20 Olle Hjortzberg, Roses in a silver vase. 75 000 SEK 20A Prins Eugen, "Båthamnen, Waldemarsudde" (The boat harbour, Waldemarsudde). 55 000 SEK 21 Bruno Liljefors, Two sea eagles and an eider duck. 620 000 SEK 22 Bruno Liljefors, Hunter with hounds and fox. 250 000 SEK 23 Bruno Liljefors, Winter landscape with hare.