Issue 18, 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (Updated 22/2/2020)

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (updated 22/2/2020) Aberargie 17-1-1855: BRIDGE OF EARN. 1890 ABERNETHY RSO. Rubber 1899. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 29-11-1969. Aberdalgie 16-8-1859: PERTH. Rubber 1904. Closed 11-4-1959. ABERFELDY 1788: POST TOWN. M.O.6-12-1838. No.2 allocated 1844. 1-4-1857 DUNKELD. S.B.17-2-1862. 1865 HO / POST TOWN. T.O.1870(AHS). HO>SSO 1-4-1918 >SPSO by 1990 >PO Local 31-7-2014. Aberfoyle 1834: PP. DOUNE. By 1847 STIRLING. M.O.1-1-1858: discont.1-1-1861. MO-SB 1-8-1879. No.575 issued 1889. By 4/1893 RSO. T.O.19-11-1895(AYL). 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 19-1-1921 STIRLING. Abernethy 1837: NEWBURGH,Fife. MO-SB 1-4-1875. No.434 issued 1883. 1883 S.O. T.O.2-1-1883(AHT) 1-4-1885 RSO. No.588 issued 1890. 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 30-9-2008 >Mobile. Abernyte 1854: INCHTURE. 1-4-1857 PERTH. 1861 INCHTURE. Closed 12-8-1866. Aberuthven 8-12-1851: AUCHTERARDER. Rubber 1894. T.O.1-9-1933(AAO)(discont.7-8-1943). S.B.9-9-1936. Closed by 1999. Acharn 9-3-1896: ABERFELDY. Rubber 1896. Closed by 1999. Aldclune 11-9-1883: BLAIR ATHOL. By 1892 PITLOCHRY. 1-6-1901 KILLIECRANKIE RSO. Rubber 1904. Closed 10-11-1906 (‘Auldclune’ in some PO Guides). Almondbank 8-5-1844: PERTH. Closed 19-12-1862. Re-estd.6-12-1871. MO-SB 1-5-1877. -

Perth & Kinross Council Archive

Perth & Kinross Council Archive Collections Business and Industry MS5 PD Malloch, Perth, 1883-1937 Accounting records, including cash books, balance sheets and invoices,1897- 1937; records concerning fishings, managed or owned by PD Malloch in Perthshire, including agreements, plans, 1902-1930; items relating to the maintenance and management of the estate of Bertha, 1902-1912; letters to PD Malloch relating to various aspects of business including the Perthshire Fishing Club, 1883-1910; business correspondence, 1902-1930 MS6 David Gorrie & Son, boilermakers and coppersmiths, Perth, 1894-1955 Catalogues, instruction manuals and advertising material for David Gorrie and other related firms, 1903-1954; correspondence, specifications, estimates and related materials concerning work carried out by the firm, 1893-1954; accounting vouchers, 1914-1952; photographic prints and glass plate negatives showing machinery and plant made by David Gorrie & Son including some interiors of laundries, late 19th to mid 20th century; plans and engineering drawings relating to equipment to be installed by the firm, 1892- 1928 MS7 William and William Wilson, merchants, Perth and Methven, 1754-1785 Bills, accounts, letters, agreements and other legal papers concerning the affairs of William Wilson, senior and William Wilson, junior MS8 Perth Theatre, 1900-1990 Records of Perth Theatre before the ownership of Marjorie Dence, includes scrapbooks and a few posters and programmes. Records from 1935 onwards include administrative and production records including -

Perth and Kinross Local Development Plan DRAFT Main Issues Report

Perth and Kinross Local Development Plan DRAFT Main Issues Report Contents Page Foreword : By Leader and E & I Convener Chapter 1 : Introduction The Development Plan The Local Development Plan What is a Main Issues Report? The Consultation Process Strategic Environmental Assessment What Happens Next? Chapter 2 : The Vision The Vision The Local Development Plan Vision Statement Local Development Plan Key Objectives Chapter 3 Drivers for Change Sustainable Development Demographic Change Population Projections What is the impact of the current economic downturn? Climate Change Sustainable Economic Growth The Rural Economy Retailing and Town Centres Perth Other retail Centres Creating Quality Places Infrastructure Needs and Constraints Primary School Secondary Schools Strategic Road Network Capacity Air Quality in Perth Funding Infrastructure Chapter 4 : Main Land Use and Delivery Issues Housing Supply & Distribution Key Issue 1 – How many houses are required? 1 Key issue 2 – Distribution at Housing Market Area level Amendments to the TAYplan Housing Requirement Key Issue 3 – how much additional housing land needs to be identified? Key Issue 4 – Density & Greenfield Land Key Issue 5 – The hierarchical approach to distribution of housing Key Issue 6 – Taking a long term view Key Issue 7 – Meeting the need across all market sectors Key Issue 8 – Housing in the Countryside Policy Economic Development land and Policies Key Issue 9 – How much additional economic development land will be required? Key Issue -

Type 6 Taxi Operator - Saloon Car

Operators List Type 6 Taxi Operator - Saloon Car Reference No. Name Address Registration No Model Colour Granted Current Renewal Current Renewal Test Date Grant Test Date 1 OP791 Alexander R Adair 81 Hugh Fraser Court SF60 HBK PEUGEOT PARTNER white 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 11/03/2016 07/11/2016 Crookfur Road Newton Mearns Glasgow G77 6JZ 2 OP337 George Adam 15 Ashmore Street SJ58 XGU Skoda Octavia Classic TDi Silver 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 10/01/2017 14/05/2017 Kirkton Dundee DD3 0DS 3 OP25 Derek Adam 2 Lintrathen Street SV61 OGU RENAULT GRAND SCENIC GREY 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 03/08/2016 04/08/2017 Dundee DD3 8EE 4 OP442 Ronald Adams 17 Cowan Place KB07 WHX VAUXHALL VECTRA SILVER 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 02/03/2016 05/11/2016 Dundee DD4 6QL 5 OP141 Ronald Addison 16 Blantyre Place SY62TBU citeron berlingo blue 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 28/09/2016 15/10/2017 Dundee DD3 8RW 6 OP351 Robert F Alexander Midcrossgate Cottages NV66GYY SKODA OCTAVIA Silver 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 14/12/2016 14/12/2017 Inchture PH14 9RN 7 OP221 James J Anderson 37 Lintrathen Gardens MV66 RLX TOYOTA AVENSIS silver 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 19/09/2016 18/09/2017 Dundee DD3 8EJ 8 OP28 David S Balbirnie 48 Dickson Avenue SP65NMK SKODA OCTAVIA red 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 05/09/2016 05/09/2017 Dundee DD2 4EG 9 OP27 Pauline Balfour 101 Hawick Drive SP57 VTX VAUXHALL VECTRA EXCLUSIV SILVER 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 09/03/2012 16/03/2013 Dundee DD4 0TB 10 OP794 Bruce Banks 2 Ardminish Place GJ15ZGZ SKODA OCTAVIA black 01/06/2016 31/05/2017 26/05/2016 26/05/2017 Dundee DD4 0SJ 11 OP92 James Barclay -

16 Coats Drive, Luncarty, Perth, PH1 3FD £210,000

www.nexthomeonline.co.uk 16 Coats Drive, Luncarty, Perth, PH1 3FD £210,000 Next Home are delighted to bring to the market this 3 BEDROOM DETACHED VILLA situated within the sought after area of Luncarty. The property comprises mainly of entrance hall, W.C., lounge, dining room, kitchen, utility room, 3 double bedrooms (master with ensuite) and family bathroom. There is double glazing and gas central heating throughout. Externally there is a mono block driveway which leads to an integral garage. The property is situated on a substantial sized plot with garden grounds to the f ront and rear. EPC RATING C. Early viewings are highly recommended to appreciate this spacious accommodation on offer. AREA Luncarty is a very desirable village which is ideally placed for accessing the A9 trunk route providing access to the North a nd South. The village offers an extensive range of amenities including a fantastic nursery, beauty and hair salon, local pub, sh op, restaurant and excellent primary school. ENTRANCE HALL 9' 6" x 6' 0" (2.9m x 1.83m) A spacious entrance hall with built in cupboard, shelving and hanging rail. Cornicing to the ceiling. Radiator. W.C. 6' 9" x 2' 9" (2.06m x 0.84m) Fitted with a two piece suite comprising of W.C. and wash hand basin with tiling to the splash back areas. Complementary vinyl flooring. Opaque window to the front. Next Home Estate Agents 63 – 65 George Street, 1a James Square, 211 High Street, 41 – 43 Allan Street, 21 Atholl Road, Perth, Crieff, Auchterarder, Blairgowrie, Pitlochry, 01738 44 43 42 01764 65 00 44 01764 66 36 66 01250 39 80 02 01796 54 80 14 www.nexthomeonline.co.uk LOUNGE 14' 8" x 11' 3" (4.47m x 3.43m) A beautifully presented public room with window to the front. -

RSPB Loch Leven on Saturday 8 August and Agricultural Awards Scheme Organised by Scottish Local Retailer Magazine

Founding editor, Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council ISSN 1757-4781 Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 431 www.kinrossnewsletter.org www.facebook.com/kinrossnewsletter July 2015 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the August Issue 5.00 pm, Friday From the Editor ..................................................................2 Letters ................................................................................2 17 July 2015 News and Articles ...............................................................4 for publication on Police Box ........................................................................14 Saturday 1 August 2015 Community Councils ........................................................15 Club & Community Group News .....................................25 Contributions for inclusion in the Sport .................................................................................36 Newsletter Out & About. ....................................................................41 The Newsletter welcomes items from community organisations and individuals for publication. This Gardens Open. ..................................................................43 is free of charge (we only charge for business News from the Rurals .......................................................44 advertising – see below right). All items may be Congratulations & Thanks ................................................44 subject to editing and we reserve the right not -

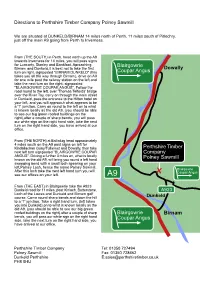

PDF Map and Directions

Directions to Perthshire Timber Company Polney Sawmill We are situated at DUNKELD/BIRNAM 14 miles north of Perth, 11 miles south of Pitlochry, just off the main A9 going from Perth to Inverness. From (THE SOUTH) in Perth, head north up the A9 towards Inverness for 14 miles, you will pass signs for Luncarty, Stanley and Bankfoot. Aproaching Blairgowrie Birnam and Dunkeld,it is best not to take the first turn on right, signposted "BIRNAM DUNKELD" (this Coupar Angus takes you all the way through Birnam), drive on A9 for one mile past the railway station on the left and take the next turn on the right, signposted "BLAIRGOWRIE COUPAR ANGUS". Follow the road round to the left, over 'Thomas Telfords' bridge over the River Tay, carry on through the main street in Dunkeld, pass the entrance to the Hilton hotel on your left, and you will approach what appears to be a 'T' junction. Carry on round to the left on to what is known locally as the old A9, (you should be able to see our big green roofed buildings on the right),after a couple of sharp bends, you will pass our white sign on the right hand side, take the next turn on the right hand side, you have arrived at our office. From (THE NORTH) at Ballinluig head approximately 4 miles south on the A9 past signs on left for Kindallachan Guay/Tulliemet and Dowally, then take Perthshire Timber next left turn signposted "BLAIRGOWRIE COUPAR Company ANGUS". Driving a further 3 miles on, what is locally Polney Sawmill known as the old A9, will bring you round a left hand sweeping bend with a small loch apearing on your left,Polney Loch, hence the name Polney Sawmill. -

Post Office Perth Directory

3- -6 3* ^ 3- ^<<;i'-X;"v>P ^ 3- - « ^ ^ 3- ^ ^ 3- ^ 3* -6 3* ^ I PERTHSHIRE COLLECTION 1 3- -e 3- -i 3- including I 3* ^ I KINROSS-SHIRE | 3» ^ 3- ^ I These books form part of a local collection | 3. permanently available in the Perthshire % 3' Room. They are not available for home ^ 3* •6 3* reading. In some cases extra copies are •& f available in the lending stock of the •& 3* •& I Perth and Kinross District Libraries. | 3- •* 3- ^ 3^ •* 3- -g Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeperthd1878prin THE POST OFFICE PERTH DIRECTORY FOR 1878 AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MARSHALL, POST OFFICE. WITH ^ Jleto ^lan of the Citg ant) i^nbixons, ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR THE WORK. PERTH: PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY LEITCH & LESLIE. PRICE THREE SHILLINGS. I §ooksz\ltmrW'Xmm-MBy & Stationers, | ^D, SILVER, COLOUR, & HERALDIC STAMPERS, Ko. 23 Qeorqe $treet, Pepjh. An extensive Stock of BOOKS IN GENERAL LITERATURE ALWAYS KEPT IN STOCK, THE LIBRARY receives special attention, and. the Works of interest in History, Religion, Travels, Biography, and Fiction, are freely circulated. STATIONEEY of the best Englisli Mannfactura.. "We would direct particular notice to the ENGRAVING, DIE -SINKING, &c., Which are carried on within the Previises. A Large and Choice Selection of BKITISK and FOEEIGU TAEOT GOODS always on hand. gesigns 0f JEonogntm^, Ac, free nf rhitrge. ENGLISH AND FOREIGN NE^A^SPAPERS AND MAGAZINES SUPPLIED REGULARLY TO ORDER. 23 GEORGE STREET, PERTH. ... ... CONTENTS. Pag-e 1. -

23X Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

23X bus time schedule & line map 23X Perth - Aberfeldy or Pitlochry View In Website Mode The 23X bus line Perth - Aberfeldy or Pitlochry has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Inveralmond: 12:14 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 23X bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 23X bus arriving. Direction: Inveralmond 23X bus Time Schedule 27 stops Inveralmond Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:14 AM Monday Not Operational Chapel Street, Aberfeldy 1 Dunkeld Street, Aberfeldy Tuesday Not Operational Industrial Estate, Aberfeldy Wednesday Not Operational Breadalbane Terrace, Aberfeldy Thursday Not Operational Caravan Site, Aberfeldy Friday Not Operational Castle, Grandtully Saturday Not Operational Croftcap Cottage, Grandtully Aultbeag Road, Little Ballinluig 23X bus Info Hotel, Grandtully Direction: Inveralmond Stops: 27 Eastertyre, Logierait Trip Duration: 52 min Line Summary: Chapel Street, Aberfeldy, Industrial Church, Logierait Estate, Aberfeldy, Caravan Site, Aberfeldy, Castle, Grandtully, Croftcap Cottage, Grandtully, Aultbeag Road, Little Ballinluig, Hotel, Grandtully, Eastertyre, Post O∆ce, Ballinluig Logierait, Church, Logierait, Post O∆ce, Ballinluig, Inn, Ballinluig, Tulliemet Road End, Ballinluig, Bus Bay, Inn, Ballinluig Kindallachan, Dowally, Rose Cottage, Inver, Bruce Gardens, Dunkeld, Royal Dunkeld Hotel, Dunkeld, Tulliemet Road End, Ballinluig North Car Park, Dunkeld, Royal Dunkeld Hotel, Dunkeld, Bruce Gardens, Dunkeld, Royal School Of Bus Bay, Kindallachan Dunkeld, Birnam, -

Plot 1, Flawcraig Neuk, Rait, Perthshire PH2 7RY

Plot 1, Flawcraig Neuk, Rait, Perthshire PH2 7RY Generous Plot Elevated Position 0.39 Acres Uninterrupted Views Outline Planning Permission Services Close By Offers Over £90,000 This is an excellent opportunity to purchase a The steep escarpment to the rear provides even DIRECTIONS generous plot with outline planning permission more seclusion and ensures that no houses could Travelling from Perth, exit the A90 at the (PKC Planning Reference 16/01172/IPL). Extending be built to the north of the plot. Inchmichael junction (signposted for Errol). Turn to around 0.39 acres, the plot lies between SERVICES right (signposted for Rait/Kilspindie/Pitroddie/ Perth and Dundee, about a mile north of the Westown/Kinnaird and follow the road for around A90 carriageway and just outside the village Mains water and electricity supplies are close by. ¾ mile. At the crossroads, turn right and the plot is of Rait. Set back from the main road with an It is proposed that the plot be serviced by a septic located approximately 1 mile along this road on elevated position, the plot offers privacy as tank system. the left, just before Flawcraig Cottage. well as uninterrupted views over the Carse of ROAD ACCESS Gowrie towards Newburgh and the Ochil Hills. From the east, exit the A90 at the Inchmichael The natural landscape is enhanced by the close Since purchasing the plot in 2014, the current junction (Signposted for Errol) and follow as proximity of a sizeable wildlife pond and mature owner has formed an access road providing entry above. trees which offer additional shelter. -

Kinross-Shire

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 388 August 2011 www.kinrossnewsletter.org ISSN 1757-4781 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the September Issue From the Editor ............................................................ 2 2.00 pm, Monday Letters ......................................................................... 2 22 August 2011 News and Articles ........................................................ 5 for publication on Police Box...................................................................15 Community Councils....................................................16 Saturday 3 September 2011 Club & Community Group News .................................21 Sport ..........................................................................30 Contributions for inclusion in the Out & About................................................................37 Newsletter Gardens Open. .............................................................39 The Newsletter welcomes items from clubs, Congratulations and Thanks..........................................40 community organisations and individuals for Kinross High School Awards ........................................41 publication. This is free of charge (we only Church Information......................................................43 charge for commercial advertising - see Playgroups & Nurseries................................................45 below right). All items may be subject to Notices........................................................................46 -

Kinross-Shire

Kinross Newsletter Founded in 1977 by Kinross Community Council. Founding Editor: Mrs Nan Walker, MBE Published by Kinross Newsletter Limited, Company No. SC374361 Issue No 407 May 2013 www.kinrossnewsletter.org ISSN 1757-4781 DEADLINE CONTENTS for the June Issue 5.00 pm, Friday From the Editor ............................................................ 2 17 May 2013 Letters ......................................................................... 2 for publication on News and Articles ........................................................ 3 Police Box...................................................................13 Saturday 1 June 2013 Community Councils....................................................14 Club & Community Group News .................................23 Contributions for inclusion in the Sport ..........................................................................37 Newsletter News from the Rurals ..................................................43 The Newsletter welcomes items from community Out & About................................................................44 organisations and individuals for publication. Gardens Open. .............................................................46 This is free of charge (we only charge for Congratulations & Thanks. ...........................................47 business advertising – see below right). All items Church Information & Obituaries..................................48 may be subject to editing and we reserve the right not to publish an item. Please also