The Journey to Light and the Road to the Restorative Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members List

MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Second Session of the Sixtieth General Assembly Speaker: The Honourable Alfie MacLeod Constituency Member Annapolis Stephen McNeil (LIB) Antigonish Angus MacIsaac (PC) Argyle Chris A. d’Entremont (PC) Bedford-Birch Cove Len Goucher (PC) Cape Breton Centre Frank Corbett (NDP) Cape Breton North Cecil Clarke (PC) Cape Breton Nova Gordie Gosse (NDP) Cape Breton South Manning MacDonald (LIB) Cape Breton West Alfie MacLeod (PC) Chester-St. Margaret’s Judy Streatch (PC) Clare Wayne Gaudet (LIB) Colchester-Musquodoboit Valley Brooke Taylor (PC) Colchester North Karen Casey (PC) Cole Harbour Darrell Dexter (NDP) Cole Harbour-Eastern Passage Becky Kent (NDP) Cumberland North Ernest Fage (I) Cumberland South Murray Scott (PC) Dartmouth East Joan Massey (NDP) Dartmouth North Trevor Zinck (NDP) Dartmouth South-Portland Valley Marilyn More (NDP) Digby-Annapolis Harold Jr. Theriault (LIB) Eastern Shore Bill Dooks (PC) Glace Bay H. David Wilson (LIB) Guysborough-Sheet Harbour Ronald Chisholm (PC) Halifax Atlantic Michèle Raymond (NDP) Halifax Chebucto Howard Epstein (NDP) Halifax Citadel-Sable Island Leonard Preyra (NDP) Halifax Clayton Park Diana Whalen (LIB) Halifax Fairview Graham Steele (NDP) Halifax Needham Maureen MacDonald (NDP) Hammonds Plains-Upper Sackville Barry Barnet (PC) Hants East John MacDonell (NDP) Hants West Chuck Porter (PC) Inverness Rodney J. MacDonald (PC) Kings North Mark Parent (PC) Kings South David Morse (PC) Kings West Leo Glavine (LIB) Lunenburg Michael Baker (PC) * Lunenburg West Carolyn Bolivar-Getson (PC) Pictou Centre Pat Dunn (PC) Pictou East Clarrie MacKinnon (NDP) Pictou West Charlie Parker (NDP) Preston Keith Colwell (LIB) Queens Vicki Conrad (NDP) Richmond Michel Samson (LIB) Sackville-Cobequid David A. -

HANSARD 19-55 DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker

HANSARD 19-55 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Kevin Murphy Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ Second Session FRIDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PRESENTING AND READING PETITIONS: Govt. (N.S.): Breast Prosthesis: MSI Coverage - Ensure, Hon. K. Regan....................................................................................................4081 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 1317, Dixon, Kayley: Prov. Volun. of the Yr. - Commend, The Premier ........................................................................................................4082 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4083 Res. 1318, Intl. Day of the Girl Child: Women in Finance, Ldrs. - Recog., Hon. K. Casey ....................................................................................................4083 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4084 Res. 1319, Dobson, Sarah/Evans, Grace: 50 Women MLAs Proj. - Congrats., Hon. K. Regan....................................................................................................4084 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................4085 Res. 1320, Maintenance Enforcement Prog.: Reducing Arrears - Recog., Hon. M. Furey ....................................................................................................4085 -

TROUT POINT LODGE, LIMITED, a Nova Scotia Limited Company; VAUGHN PERRET and CHARLES LEARY, Plaintiff, Civil Action No.: 1:12-CV-90LG-JMR V

Case 1:12-cv-00090-LG-JMR Document 27 Filed 08/06/12 Page 1 of 10 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI SOUTHERN DIVISION TROUT POINT LODGE, LIMITED, A Nova Scotia Limited Company; VAUGHN PERRET and CHARLES LEARY, Plaintiff, Civil Action No.: 1:12-CV-90LG-JMR v. DOUG K. HANDSHOE, Defendant. * * * * * * * * * * * * * SUPPLEMENTAL REPLY MEMORANDUM OF DEFENDANT, DOUGLAS K. HANDSHOE MAY IT PLEASE THE COURT: This Supplemental Memorandum is submitted by defendant, Douglas K. Handshoe (“Handshoe”), in reply to the Memorandum in Opposition to Motion for Summary Judgment, which was filed by the plaintiffs, Trout Point, Vaughn Perret, and Charles Leary (collectively, “Trout Point”). As previously discussed in defendant’s Reply Memorandum, the parties agreed that this dispute would focus on pure questions of law, rather than specific facts, and would be resolved solely on motions for summary judgment. Still, as pointed out in defendant’s Reply Memorandum, plaintiffs have focused a great deal of their arguments on facts. Because of plaintiffs’ harping on the facts, defendant feels compelled to provide the court with factual points as well. Thus, this supplemental memorandum will focus on revealing the factual bases for defendant’s allegedly defamatory statements. Case 1:12-cv-00090-LG-JMR Document 27 Filed 08/06/12 Page 2 of 10 Plaintiffs repeatedly point to the assertion that in the Canadian adjudication, they proved that the statements made about them were false. Specifically, they state in their Response to Memorandum in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment that plaintiffs have clearly demonstrated that the statements were false and defamatory. -

Members List

MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Second Session of the Sixty-First General Assembly Speaker: The Honourable Charlie Parker1 Constituency Member Annapolis Stephen McNeil (LIB) Antigonish Maurice Smith (NDP) Argyle Chris A. d’Entremont (PC) Bedford-Birch Cove Kelly Regan (LIB) Cape Breton Centre Frank Corbett (NDP) Cape Breton North Cecil Clarke (PC)2 Cape Breton Nova Gordie Gosse (NDP) Cape Breton South Manning MacDonald (LIB) Cape Breton West Alfie MacLeod (PC) Chester-St. Margaret’s Denise Peterson-Rafuse (NDP) Clare Wayne Gaudet (LIB) Colchester-Musquodoboit Valley Gary Burrill (NDP) Colchester North Karen Casey (PC)3 Cole Harbour Darrell Dexter (NDP) Cole Harbour-Eastern Passage Becky Kent (NDP) Cumberland North Brian Skabar (NDP) Cumberland South Murray Scott (PC)4 Dartmouth East Andrew Younger (LIB) Dartmouth North Trevor Zinck (I) Dartmouth South-Portland Valley Marilyn More (NDP) Digby-Annapolis Harold Jr. Theriault (LIB) Eastern Shore Sidney Prest (NDP) Glace Bay Geoff MacLellan (LIB)5 Guysborough-Sheet Harbour Jim Boudreau (NDP) Halifax Atlantic Michèle Raymond (NDP) Halifax Chebucto Howard Epstein (NDP) Halifax Citadel-Sable Island Leonard Preyra (NDP) Halifax Clayton Park Diana Whalen (LIB) Halifax Fairview Graham Steele (NDP) Halifax Needham Maureen MacDonald (NDP) Hammonds Plains-Upper Sackville Mat Whynott (NDP) Hants East John MacDonell (NDP) Hants West Chuck Porter (PC) Inverness Allan MacMaster (PC) Kings North Jim Morton (NDP) Kings South Ramona Jennex (NDP) Kings West Leo Glavine (LIB) Lunenburg Pam Birdsall(NDP) Lunenburg West Gary Ramey (NDP) Pictou Centre Ross Landry (NDP) Pictou East Clarrie MacKinnon (NDP) Pictou West Charlie Parker (NDP) Preston Keith Colwell (LIB) Queens Vicki Conrad (NDP) Richmond Michel Samson (LIB) Sackville-Cobequid David A. -

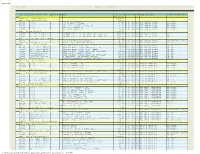

Report Output

Report output 03.03.2011 Dynamic List Display 1 Cost Elem. Cost element name Quantity PUM Name Val.in RC Postg Date Year Supp Code Name Document Header Text *** 221,644.64 ** Annapolis - Member Expenses 4,269.36 * Anna - Other Travel Expenses 819.56 638100 M L A JAN 24-27, COMMUTE 4 127.98 10.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL JAN TRAVEL 638100 M L A JAN 31-FEB 3, COMMUTE 5 127.98 10.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL JAN TRAVEL 638100 M L A JAN 25-27, CAUCUS 1, HOTEL, PD 307.64 10.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL JAN TRAVEL 638100 M L A FEB 7-12, COMMUTE 6 127.98 23.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL FEB TRAVEL 638100 M L A FEB 14-20, COMMUTE 7 127.98 23.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL FEB TRAVEL * Anna - Living Expenses 1,640.00 639100 MLA Living Allowance 2730979 CANADA INC, FEB, RENT 1,640.00 11.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL FEB LA 639100 MLA Living Allowance 2739079 CANADA INC, FEB RENT, REF 3200711615 1,640.00 28.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL FEB LA 639100 MLA Living Allowance 2739079 CANADA INC, FEB RENT, REF 3200711615 1,640.00- 28.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL FEB LA * Anna - Franking and Travel Expenses 303.88 638100 M L A JAN 1-30, FRANKING & TRAVEL 243.70 09.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL JAN FRANKING & TRAVEL 761400 Postage CANADA POST, TR628069, POSTAGE 60.18 09.02.2011 2010 HON STEPHEN MCNEIL JAN EXP * Anna - Constituency Expenses 1,505.92 761200 Misc. -

Legislative Proceedings

HANSARD 12-44 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Gordon Gosse Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ Fourth Session WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE STATEMENTS BY MINISTERS: Com. Serv.: Affordable Housing - Plan, Hon. D. Peterson-Rafuse....................................................................................3320 ERDT - PROJEX Technologies: Halifax - Expansion, The Premier ........................................................................................................3323 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 1800, Crohn’s & Colitis Awareness Mo. (11/12) - Recognize, Hon. D. Wilson .............................................................................3327 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................3327 Res. 1801, Take Our Kids to Work Day: Importance - Recognize, Hon. R. Jennex ..............................................................................3328 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................3329 Res. 1802, Creative N.S. Leadership Awards: Winners/Finalists - Congrats., Hon. L. Preyra ................................................................................3329 Vote - Affirmative..................................................................................3329 Res. 1803, Haynes, Michael: Hiking Trails of Mainland -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 86 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................96 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................94 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar..........................................95 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer.....................................96 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston......................................98 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ................................99 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ......................................96 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong..................................96 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ..............................98 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .........................................96 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson................................98 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

Hansard 10-55 Debates And

HANSARD 10-55 DEBATES AND PROCEEDINGS Speaker: Honourable Charlie Parker Published by Order of the Legislature by Hansard Reporting Services and printed by the Queen's Printer. Available on INTERNET at http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/proceedings/hansard/ Second Session WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 1, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PRESENTING REPORTS OF COMMITTEES: Law Amendments Committee, Mr. D. Wilson ........................................ 4407 Law Amendments Committee, Mr. D. Wilson ........................................ 4408 GOVERNMENT NOTICES OF MOTION: Res. 2600, Mainstay Award: Winners - Congrats., Hon. M. More ........................................ 4408 Vote - Affirmative ................................ 4409 Res. 2601, Hurricane Earl: Preparedness - Acknowledge, Hon. R. Jennex ....................................... 4409 Vote - Affirmative ................................ 4410 Res. 2602, World AIDS Day (12/01/10): Importance - Recognize, Hon. Maureen MacDonald (by Hon. G. Steele) .............. 4410 Vote - Affirmative ................................ 4411 Res. 2603, Meat Cove - Flooding (08/10): Response - Recognize, Hon. R. Jennex ....................................... 4411 Vote - Affirmative ................................ 4411 Res. 2604, EHS: Accreditation - Congrats. Hon. Maureen MacDonald (by Hon. G. Steele) .............. 4411 Vote - Affirmative ................................ 4412 Res. 2605, St. F.X.: African Cdn. Serv. Div. - Partnership, Hon. P. Paris (by Hon. J. MacDonell) ..................... 4412 Vote - Affirmative -

Journals and Proceedings

APPENDIX C STATUS OF BILLS C-2 STATUS OF BILLS Bill 1. House of Assembly Management Commission Act Honourable Darrell E. Dexter - President of the Executive Council First Reading . March 26, 2010 Second Reading. May 7, 2010 Law Amendments Committee. May 11, 2010 Committee of the Whole House . May 11, 2010 Third Reading . May 11, 2010 Royal Assent . May 11, 2010 Commencement. Royal Assent 2010 Statutes . Chapter 5 Bill 2. Health Act - amended Honourable Stephen McNeil - Annapolis First Reading . March 26, 2010 Bill 3. Provincial Finance Act - amended Leo Glavine - Kings West First Reading . March 26, 2010 Bill 4. Electricity Act - amended Andrew Younger - Dartmouth East First Reading . March 26, 2010 Bill 5. Provincial Finance Act - amended Leo Glavine - Kings West First Reading . March 26, 2010 Bill 6. Industrial Expansion Fund Transfer Act Honourable Stephen McNeil - Annapolis First Reading . March 29, 2010 STATUS OF BILLS C-3 Bill 7. Pharmacy Act - amended Honourable Maureen MacDonald - Minister of Health First Reading . March 29, 2010 Second Reading. May 7, 2010 Law Amendments Committee. November 17, 2010 Committee of the Whole House . November 25, 2010 Third Reading . November 25, 2010 Royal Assent . December 10, 2010 Commencement. Royal Assent 2010 Statutes . Chapter 67 Bill 8. Multi-Year Funding Act Honourable Manning MacDonald, C.D. - Cape Breton South First Reading . March 29, 2010 Bill 9. Advisory Council on Mental Health Act Diana Whalen - Halifax Clayton Park First Reading . March 29, 2010 Bill 10. Cape Breton Island Marketing Levy Act - amended Honourable Percy A. Paris - Minister of Tourism, Culture and Heritage First Reading . March 30, 2010 Second Reading. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 88 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Saanich South .........................................Lana Popham ....................................100 Shuswap..................................................George Abbott ....................................95 Total number of seats ................85 Skeena.....................................................Robin Austin.......................................95 Liberal..........................................49 Stikine.....................................................Doug Donaldson .................................97 New Democratic Party ...............35 Surrey-Cloverdale...................................Kevin Falcon.......................................97 Independent ................................1 Surrey-Fleetwood ...................................Jaqrup Brar..........................................96 Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................97 Abbotsford South....................................John van Dongen ..............................101 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................95 Abbotsford West.....................................Michael de Jong..................................97 Surrey-Panorama ....................................Stephanie Cadieux -

VICTORIA COUNTY MUNICIPAL COUNCIL January 10, 2011 A

VICTORIA COUNTY MUNICIPAL COUNCIL January 10, 2011 A meeting of Victoria County Municipal Council was held at the Court House, Baddeck, on Monday, January 10, 2011, beginning at 5:00 p.m. with Warden Bruce Morrison in the Chair. Present were: District #1 – Paul MacNeil District #2 – Keith MacCuspic District #3 – Bruce Morrison, Warden District #4 – Merrill MacInnis District #5 – Fraser Patterson, Deputy Warden District #6 – Larry Dauphinee District #7 – David Donovan District #8 – Johnny Buchanan Also present were: Sandy Hudson, CAO Heather MacLean, Recording Secretary CALL TO ORDER/APPROVAL OF AGENDA Warden Morrison called the meeting to order and extended a Happy New Year to all present. The agenda was presented for approval. It was moved by Councillor MacInnis, seconded by Councillor Buchanan, that the agenda be approved as presented. Motion carried. Warden Morrison also welcomed Alicia Lake, a Political Science Major at CBU, who was in attendance to observe the workings of Council. DEBBIE NIELSEN, UNSM SUSTAINABILITY COORDINATOR Courtesy of Council was extended to Debbie Nielsen, UNSM Sustainability Coordinator, who was in attendance to make a presentation on the projects being undertaken and the resources available through the UNSM Sustainability Office. Ms. Nielsen began by stating that sustainability is an opportunity to look at how to do things better and more efficiently which results in saving energy and dollars. She then made her presentation on the origins the Sustainability Office; projects undertaken and presently being worked on; awareness raising and education initiatives; Page 2, VICTORIA COUNTY MUNICIPAL COUNCIL, January 10, 2011 building capacities through partnerships and consultation on provincial strategies (copy attached). -

Ref.: NSE LCC Threshold TP2014 (21 Pages) To: Hon. (Prof.) Randy Delorey, Minister, Nova Scotia Environment Dept Cc (All Rt

Soil & Water Conservation Society of Metro Halifax (SWCSMH) 310-4 Lakefront Road, Dartmouth, NS, Canada B2Y 3C4 Email: [email protected] Tel: (902) 463-7777 Master Homepage: http://lakes.chebucto.org Ref.: NSE_LCC_Threshold_TP2014 (21 pages) To: Hon. (Prof.) Randy Delorey, Minister, Nova Scotia Environment Dept Cc (all Rt. Hon. Stephen McNeil, Hon. Diana C. Whalen, Hon. Andrew Younger, Hon. Lena MLAs w/in Metlege Diab, Hon. Keith Colwell, Hon. Tony Ince, Hon. Kelly Regan, Hon. Joanne the HRM Bernard, Hon. Labi Kousoulis, Hon. Kevin Murphy, Hon. Maureen MacDonald, Hon. area): Denise Peterson-Rafuse, Hon. Dave Wilson, Mr. Allan Rowe, Mr. Stephen Gough, Mr. Brendan Maguire, Mr. Bill Horne, Ms. Patricia Arab, Mr. Ben Jessome, Mr. Iain Rankin, Mr. Joachim Stroink, Ms. Joyce Treen From: S. M. Mandaville Post-Grad Dip., Professional Lake Manage. Chairman and Scientific Director Date: March 14, 2014 Subject: Phosphorus:- Details on LCC (Lake Carrying Capacity)/Threshold values of lakes, and comparison with artificially high values chosen by the HRM We are an independent scientific research group with some leading scientists across Canada and the USA among our membership. Written informally. I provide web scans where necessary as backup to Government citations. Pardon any typos/grammar. T-o-C: Subject/Topic Page #s Overview 2 Introduction 2 Eutrophication 4 Potential sources of phosphorus 4 CCME (Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment)’s guidance 5 table --- --- Conclusions of the 18-member countries of the OECD (Organization for