Curriculum Vitae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholland Masters Thesis Final Draft

Copyright By Christopher Paul Holland 2010 The Thesis committee for Christopher Paul Holland Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder ___________________________________ Gail Minault Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Rethinking Qawwali: Perspectives of Sufism, Music, and Devotion in North India by Christopher Paul Holland, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Scholarship has tended to focus exclusively on connections of Qawwali, a north Indian devotional practice and musical genre, to religious practice. A focus on the religious degree of the occasion inadequately represents the participant’s active experience and has hindered the discussion of Qawwali in modern practice. Through the examples of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s music and an insightful BBC radio article on gender inequality this thesis explores the fluid musical exchanges of information with other styles of Qawwali performances, and the unchanging nature of an oral tradition that maintains sociopolitical hierarchies and gender relations in Sufi shrine culture. Perceptions of history within shrine culture blend together with social and theological developments, long-standing interactions with society outside of the shrine environment, and an exclusion of the female body in rituals. -

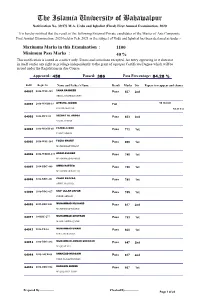

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final)

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 39/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final) First Annual Examination, 2020 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite First Annual Examination, 2020 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under:- Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -5E -4E Appeared: 458 Passed: 386 Pass Percentage: 84.28 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance 64001 2016-WST-348 SANA RASHEED Pass 637 2nd ABDUL RASHEED KHAN VII IX X XI 64002 2016-WNDR-19 AYESHA JAVAID Fail JAVAID AKHTAR R/A till S-22 64003 2014-IWY-88 SEERAT UL AROOJ Pass 653 2nd NASIR AHMAD 64004 2016-MOCB-05 FAZEELA BIBI Pass 712 1st JAM GAMMON 64005 2016-WST-164 FOZIA SHARIF Pass 690 1st MUHAMMAD SHARIF 64006 2016-WBDR-173 ANAM ASGHAR Pass 740 1st MUHAMMAD ASGHAR 64007 2018-BDC-440 AMNA RAFEEQ Pass 730 1st MUHAMMAD RAFEEQ 64008 2016-BDC-481 ZAHID RAZZAQ Pass 741 1st ABDUL RAZZAQ 64009 2016-BDC-427 SAIF ULLAH ZAFAR Pass 745 1st ZAFAR AHMAD 64010 2015-BDC-623 MUHAMMAD MUJAHID Pass 617 2nd MUHAMMAD AKRAM 64011 10-BDC-277 MUHAMMAD GHUFRAN Pass 753 1st MALIK ABDUL QADIR 64012 2016-US-16 MUHAMMAD UMAIR Pass 660 1st GHULAM RASOOL 64013 2016-BDC-434 MUHAMMAD AHMAD SHEHZAD Pass 647 2nd LIAQUAT ALI 64014 2015-AICB-08 SHAHZAD HUSSAIN Pass 617 2nd SYED SAJJAD HUSSAIN 64015 2016-BDC-542 HASNAIN AHMED Pass 667 1st MULAZIM HUSSAIN Prepared By--------------- Checked By-------------- Page 1 of 24 Roll# Regd. -

Visual Foxpro

RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT BHINDER IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/2/2003 33835 Sh.Bhagwati Lal Choubisa N.A.* 2 R/223/2007 47749 Sh.Laxman Giri Goswami L.T.M. 3 R/393/2018 82462 Sh.Manoj Kumar Regar N.A.* 4 R/3668/2018 85737 Kum.Kalavati Choubisa N.A.* 5 R/2130/2020 93493 Sh.Lokesh Kumar Regar N.A.* 6 R/59/2021 94456 Sh.Kailash Chandra Khariwal L.T.M. 7 R/3723/2021 98120 Sh.Devi Singh Charan N.A.* Total RAWF Members = 2 Total Terminated = 0 Total Defaulter = 0 N.A.* => Not Applied for Membership, L.T.M. => Life Time Member, Termi => Terminated Member RAJASTHAN ADVOCATES WELFARE FUND C/O THE BAR COUNCIL OF RAJASTHAN HIGH COURT BUILDINGS, JODHPUR Showing Complete List of Advocates Due Subscription of R.A.W.F. AT GOGUNDA IN UDAIPUR JUDGESHIP DATE 06/09/2021 Page 1 Srl.No.Enrol.No. Elc.No. Name as on the Roll Due Subs upto 2021-22+Advn.Subs for 2022-23 Life Time Subs with Int. upto Sep 2021 ...Oct 2021 upto Oct 2021 (A) (B) (C) (D) (E) (F) 1 R/460/1975 6161 Sh.Purushottam Puri NIL + 1250 = 1250 1250 16250 2 R/337/1983 11657 Sh.Kanhiya Lal Soni 6250+2530+1250=10030 10125 25125 3 R/125/1994 18008 Sh.Yuvaraj Singh L.T.M. -

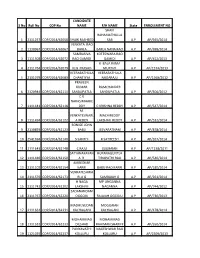

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

CC-7: HISTORY of INDIA (C.1206-1526) IV

CC-7: HISTORY OF INDIA (c.1206-1526) IV. RELIGION AND CULTURE (A). SUFI SILSILAS: CHISHTIS AND SUHRAWARDIS; DOCTRINES AND PRACTICES; SOCIAL ROLES (C). SUFI LITERATURE, MALFUZAT; PREMAKHAYANS The tenth century is important in Islamic history for a variety of reasons: it marks the rise of the Turks on the runs of the Abbasid Caliphate, as well as important changes in the realm of the ideas and beliefs. In the realm of ideas, it marks the end of the domination of the Mutazila or rationalist philosophy, and the rise of orthodox schools based on the Quran and Hadis (traditions of the Prophet and his companions) and of the Sufi mystic orders. The word Sufi is derived from ‘suf’ which means wool in Arabic, referring the simple cloaks the early Muslim ascetics wore. It also means ‘purity’ and thus can be understood as the one who wears wool on top of purity. The Sufis were regarded as people who kept their heart pure and who sought to communicate with God through their ascetic practice. Sufism or mysticism emerged in the 8th century and the early known Sufis were Rabiya al-Adawiya, Al-Junaid and Bayazid Bastami. However, it evolved into a well-developed movement by the end of the 11th century. Al-Hujwiri, who established himself in north India was buried in Lahore and regarded as the oldest Sufi in the sub-continent. By the 12th century, the Sufis were organised in Silsilahs (i,e., orders, which basically represented an unbreakable chain between the Pir, the teacher, and the murids, the disciples). -

A SUFI ‘FRIEND of GOD’ and HIS ZOROASTRIAN CONNECTIONS: the Paradox of Abū Yazīd Al-Basṭāmī ______Kenneth Avery

SAJRP Vol. 1 No. 2 (July/August 2020) A SUFI ‘FRIEND OF GOD’ AND HIS ZOROASTRIAN CONNECTIONS: The Paradox of Abū Yazīd al-Basṭāmī ____________________________________________________ Kenneth Avery ABSTRACT his paper examines the paradoxical relation between the T famed Sufi ‘friend’ Abū Yazīd al-Basṭāmī (nicknamed Bāyazīd; d. 875 C.E. or less likely 848 C.E.) and his Zoroastrian connections. Bāyazīd is renowned as a pious ecstatic visionary who experienced dream journeys of ascent to the heavens, and made bold claims of intimacy with the Divine. The early source writings in both Arabic and Persian reveal a holy man overly concerned with the wearing and subsequent cutting of the non- Muslim zunnār or cincture. This became a metaphor of his constant almost obsessive need for conversion and reconversion to Islam. The zunnār also acts as a symbol of infidelity and his desire to constrict his lower ego nafs. The experience of Bāyazīd shows the juxtaposition of Islam with other faiths on the Silk Road in 9th century Iran, and despite pressures to convert, other religions were generally tolerated in the early centuries following the Arab conquests. Bāyazīd’s grandfather was said to be a Zoroastrian and the family lived in the Zoroastrian quarter of their home town Basṭām in northeast Iran. Bāyazīd shows great kindness to his non-Muslim neighbours who see in him the best qualities of Sufi Islam. The sources record that his saintliness influenced many to become Muslims, not unlike later Sufi missionaries among Hindus and Buddhists in the subcontinent. 1 Avery: Sufi Friend of God INTRODUCTION Bāyazīd’s fame as a friend of God is legendary in Sufi discourse. -

An Analysis of Al-Hakim Al-Tirmidhi's Mystical

AN ANALYSIS OF AL-HAKIM AL-TIRMIDHI’S MYSTICAL IDEOLOGY BASED ON BOOKS: BADʼU SHAANI AND SIRAT AL-AWLIYA Kazem Nasirizare, Ph.D. Candidate in Persian Language and Literature University of Zanjan, Iran Mehdi Mohabbati, Ph.D. Professor. at Department of Persian Language and Literature University of Zanjan Abstract. Abu Abdullah Muhammad bin Hasan bin Bashir Bin Harun Al Hakim Al-Tirmidhi, also called Al- Hakim Al-Tirmidhi, is a Persian mystic living in the 3rd century AH. He is important in the history of Persian literature and the Persian-Islamic mysticism due to several reasons. First, he is one of the first Persian mystics who has significant works in the field of mysticism. Second, early instances of Persian prose can be identified in his world and taking the time that he was living into consideration, the origins of post-Islam Persian prose can be seen in his writings. Third, his ideas have had significant impacts on Mysticism, Sufism, and consequently, in the Persian mystical literature; thus, understanding and analyzing his viewpoints and works is of significant importance for attaining a better picture of Persian mystical literature. The current study attempts to analyze Al-Tirmidhi’s mystical ideology based on his two books: Bad’u Shanni Abu Abdullah (The Beginning of Abu Abdullah’s Journey) and Sirat Al-Awliya (Road of the Saints). Al-Tirmidhi’s ideology is going to be explained through investigating and analyzing his viewpoints regarding the manner of starting a spiritual journey, the status of asceticism and austerity in a spiritual journey, transition from the ascetic school of Baghdad to the Romantic school of Khorasan. -

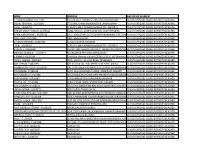

Name Address Nature of Payment P

NAME ADDRESS NATURE OF PAYMENT P. NAVEENKUMAR -91774443 NO 139 KALATHUMEDU STREETMELMANAVOOR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED VISHAL TEKRIWAL -31262196 27,GOPAL CHANDRAMUKHERJEE LANEHOWRAH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED BHIKAM SINGH THAKUR -21445522 JABALPURS/O UDADET SINGHVILL MODH PIPARIYA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ATINAINARLINGAM S -91828130 NO 2 HINDUSTAN LIVER COLONYTHAGARAJAN STREET PAMMAL0CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED USHA DEVI -27227284 VPO - SILOKHARA00 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUSHMA BHENGRA -19404716 A-3/221,SECTOR-23ROHINI CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAKESH V -91920908 NO 304 2ND FLOOR,THIRUMALA HOMES 3RD CROSS NGRLAYOUT,CLAIMS CHEQUES ROOPENA ISSUED AGRAHARA, BUT NOT ENCASHED KRISHAN AGARWAL -21454923 R/O RAJAPUR TEH MAUCHITRAKOOT0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED K KUMAR -91623280 2 nd floor.olympic colonyPLOT NO.10,FLAT NO.28annanagarCLAIMS west, CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MOHD. ARMAN -19381845 1571, GALI NO.-39,JOOR BAGH,TRI NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ANIL VERMA -21442459 S/O MUNNA LAL JIVILL&POST-KOTHRITEH-ASHTA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAMBHAVAN YADAV -21458700 S/O SURAJ DEEN YADAVR/O VILG GANDHI GANJKARUI CHITRAKOOTCLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD SHADAB -27188338 H.NO-10/242 DAKSHIN PURIDR. AMBEDKAR NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD FAROOQUE -31277841 3/H/20 RAJA DINENDRA STREETWARD NO-28,K.M.CNARKELDANGACLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAJIV KUMAR -13595687 CONSUMER APPEALCONSUMERCONSUMER CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MUNNA LAL -27161686 H NO 524036 YARDS, SECTOR 3BALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUNIL KUMAR -27220272 S/o GIRRAJ SINGHH.NO-881, RAJIV COLONYBALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED DIKSHA ARORA -19260773 605CELLENO TOWERDLF IV CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED R. -

From Rabi`A to Ibn Al-Färich Towards Some Paradigms of the Sufi Conception of Love

From Rabi`a to Ibn al-Färich Towards Some Paradigms of the Sufi Conception of Love By Suleyman Derin ,%- Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Department of Arabic and 1Viiddle Eastern Studies The University of Leeds The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. September 1999 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to investigate the significance of Divine Love in the Islamic tradition with reference to Sufis who used the medium of Arabic to communicate their ideas. Divine Love means the mutual love between God and man. It is commonly accepted that the Sufis were the forerunners in writing about Divine Love. However, there is a relative paucity of literature regarding the details of their conceptions of Love. Therefore, this attempt can be considered as one of the first of its kind in this field. The first chapter will attempt to define the nature of love from various perspectives, such as, psychology, Islamic philosophy and theology. The roots of Divine Love in relation to human love will be explored in the context of the ideas that were prevalent amongst the Sufi authors regarded as authorities; for example, al-Qushayri, al-Hujwiri and al-Kalabadhi. The second chapter investigates the origins Of Sufism with a view to establishing the role that Divine Love played in this. The etymological derivations of the term Sufi will be referred to as well as some early Sufi writings. It is an undeniable fact that the Qur'an and tladith are the bedrocks of the Islamic religion, and all Muslims seek to justify their ideas with reference to them. -

Reforming Madrasa Education in Pakistan; Post 9/11 Perspectives Ms Fatima Sajjad

Volume 3, Issue 1 Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization Spring 2013 Reforming Madrasa Education in Pakistan; Post 9/11 Perspectives Ms Fatima Sajjad Abstract Pakistani madrasa has remained a subject of intense academic debate since the tragic events of 9/11 as they were immediately identified as one of the prime suspects. The aim of this paper is to examine the post 9/11 academic discourse on the subject of madrasa reform in Pakistan and identify the various themes presented in them. This paper also seeks to explore the missing perspective in this discourse; the perspective of ulama; the madrasa managers, about the Western demand to reform madrasa. This study is based on qualitative research methods. To evaluate the views of academia, this study relies on a systematic analysis of the post 9/11 discourse on this subject. To find out the views of ulama, in-depth interviews of leading Pakistani ulama belonging to all major schools of thought have been conducted. The study finds that many fears generated by early post 9/11 studies were rejected by the later ones. This study also finds that contrary to the common perception the leading ulama in Pakistan are open to the idea of madrasa reform but they prefer to do it internally as an ongoing process and not due to outside pressure. This study recommends that in order to resolve the madrasa problem in Pakistan, it is imperative to take into account the ideas and concerns of ulama running them. It is also important to take them on board in the fight against the religious militancy and terrorism in Pakistan. -

Khawaja and the 'Amazing Bros'

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE - COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES NSP 1 - PSN 1 DIRECTED RESEARCH PROJECT May 18, 2009 KHAWAJA AND THE ‘AMAZING BROS’: A TEST OF CANADA’S ANTI-TERRORISM LAWS AS A RESPONSE TO THE CHALLENGES OF TRANSNATIONAL TERRORISM By/par DEBRA W. ROBINSON This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par attending the Canadian Forces un stagiaire du Collège des Forces College in fulfillment of one of the canadiennes pour satisfaire à l’une requirements of the Course of des exigences du cours. L’étude est Studies. The paper is a scholastic un document qui se rapporte au cours document, and thus contains facts et contient donc des faits et des and opinions which the author opinions que seul l’auteur considère alone considered appropriate and appropriés et convenables au sujet. -

Jihadist Violence: the Indian Threat

JIHADIST VIOLENCE: THE INDIAN THREAT By Stephen Tankel Jihadist Violence: The Indian Threat 1 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program ISBN: 978-1-938027-34-5 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and interna- tional affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan insti- tution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Thomas R. Nides, Chairman of the Board Sander R. Gerber, Vice Chairman Jane Harman, Director, President and CEO Public members: James H.