Kurdish Question”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS POLICY FOCUS 137 Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2015 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: A Kurdish fighter keeps guard while overlooking positions of Islamic State mili- tants near Mosul, northern Iraq, August 2014. (REUTERS/Youssef Boudlal) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Acronyms | vi Executive Summary | viii 1 Introduction | 1 2 Federal Government Security Forces in Iraq | 6 3 Security Forces in Iraqi Kurdistan | 26 4 Optimizing U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq | 39 5 Issues and Options for U.S. Policymakers | 48 About the Author | 74 TABLES 1 Effective Combat Manpower of Iraq Security Forces | 8 2 Assessment of ISF and Kurdish Forces as Security Cooperation Partners | 43 FIGURES 1 ISF Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 10 2 Kurdish Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 28 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to a range of colleagues for their encouragement and assistance in the writing of this study. -

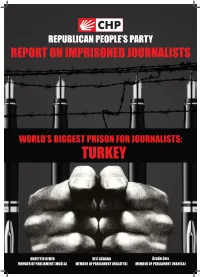

Report on Imprisoned Journalists

REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MALATYA) MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MANİSA) REPUBLICAN PEOPLE’S PARTY PRISON EXAMINATION AND WATCH COMMISSION REPORT ON IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS WORLD’S BIGGEST PRISON FOR JOURNALISTS: TURKEY NURETTİN DEMİR VELİ AĞBABA ÖZGÜR ÖZEL MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT (MUĞLA) (MALATYA) (MANİSA) CONTENTS PREFACE, Ercan İPEKÇİ, General Chairman of the Union of Journalists in Turkey ....... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 11 2. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON: OBSERVATIONS AND FINDINGS .................. 17 3. JOURNALISTS IN PRISON .......................................................................... 21 3.1 Journalists Put on Trial on Charges of Committing an Off ence against the State and Currently Imprisoned ................................................................................ 21 3.1.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ........................................................................ 21 3.2 Journalists Put on Trial in Association with KCK (Union of Kurdistan Communities) and Currently Imprisoned .................................... 32 3.2.1Information on a Number of Arrested/Sentenced Journalists and Findings on the Reasons for their Arrest ....................................................................... -

Turkey's Deep State

#1.12 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey FEATURE ARTICLES TURKEY’S DEEP STATE CULTURE INTERNATIONAL POLITICS ECOLOGY AKP’s Cultural Policy: Syria: The Case of the Seasonal Agricultural Arts and Censorship “Arab Spring” Workers in Turkey Pelin Başaran Transforming into the Sidar Çınar Page 28 “Arab Revolution” Page 32 Cengiz Çandar Page 35 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Content Editor’s note 3 ■ Feature articles: Turkey’s Deep State Tracing the Deep State, Ayşegül Sabuktay 4 The Deep State: Forms of Domination, Informal Institutions and Democracy, Mehtap Söyler 8 Ergenekon as an Illusion of Democratization, Ahmet Şık 12 Democratization, revanchism, or..., Aydın Engin 16 The Near Future of Turkey on the Axis of the AKP-Gülen Movement, Ruşen Çakır 18 Counter-Guerilla Becoming the State, the State Becoming the Counter-Guerilla, Ertuğrul Mavioğlu 22 Is the Ergenekon Case an Opportunity or a Handicap? Ali Koç 25 The Dink Murder and State Lies, Nedim Şener 28 ■ Culture Freedom of Expression in the Arts and the Current State of Censorship in Turkey, Pelin Başaran 31 ■ Ecology Solar Energy in Turkey: Challenges and Expectations, Ateş Uğurel 33 A Brief Evaluation of Seasonal Agricultural Workers in Turkey, Sidar Çınar 35 ■ International Politics Syria: The Case of the “Arab Spring” Transforming into the “Arab Revolution”, Cengiz Çandar 38 Turkey/Iran: A Critical Move in the Historical Competition, Mete Çubukçu 41 ■ Democracy 4+4+4: Turning the Education System Upside Down, Aytuğ Şaşmaz 43 “Health Transformation Program” and the 2012 Turkey Health Panorama, Mustafa Sütlaş 46 How Multi-Faceted are the Problems of Freedom of Opinion and Expression in Turkey?, Şanar Yurdatapan 48 Crimes against Humanity and Persistent Resistance against Cruel Policies, Nimet Tanrıkulu 49 ■ News from hbs 53 Heinrich Böll Stiftung – Turkey Representation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. -

The Making and Unmaking of Syria Strategy Under Trump

REPORT SYRIA The Making and Unmaking of Syria Strategy under Trump NOVEMBER 29, 2018 — ARON LUND PAGE 1 The most effective way to change the world these days seems to be to plant a message directly in the brain of its most powerful inhabitant: Donald J. Trump, president of the United States of America. Although the U.S. executive branch always had a fairly free hand in foreign policy, ideas would normally need to snake their way through a whole series of interagency deliberations before landing on the Oval Office desk for a final verdict. But as media leaks and disgruntled former members of the Trump administration have made abundantly clear, decision- making in the current White House is both more temperamental and more personalized, revolving around a president known for forming strong opinions based on ideas picked up from television, friends, and other outside sources. Advocates inside and outside the U.S. government increasingly seem to operate under the assumption that the best way to influence American policy is to sidestep the bureaucracy and speak directly to an audience of one: Donald Trump. And, last September, that’s exactly what two pro-opposition Syrian-Americans managed to do after paying a Republican lobbyist to get seats at an Indiana fundraising dinner.1 President Trump later told the story: I was at a meeting with a lot of supporters, and a woman stood up and she said, “There’s a province in Syria with 3 million people. Right now, the Iranians, the Russians, and the Syrians are surrounding their province. -

The 'New Middle East,' Revised Edition

9/29/2014 Diplomatist BILATERAL NEWS: India and Brazil sign 3 agreements during Prime Minister's visit to Brazil CONTENTS PRINT VERSION SPECIAL REPORTS SUPPLEMENTS OUR PATRONS MEDIA SCRAPBOOK Home / September 2014 The ‘New Middle East,’ Revised Edition GLOBAL CENTRE STAGE In July 2014, President Obama sent the White House’s Coordinator for the Middle East, Philip Gordon, to address the ‘Israel Conference on Peace’ in Tel-Aviv. ‘How’ Gordon asked ‘will [Israel] have peace if it is unwilling to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity?’ This is a good question, but Dr Emmanuel Navon asks how Israel will achieve peace if it is willing to delineate a border, end the occupation and allow for Palestinian sovereignty, security, and dignity, especially when experience, logic and deduction suggest that the West Bank would turn into a larger and more lethal version of the Gaza Strip after the Israeli withdrawal During the last war between Israel and Hamas (which officially ended with a ceasefire on August 27, 2014), US Secretary of State John Kerry inadvertently created a common ground among rivals: Israel, the Palestinian Authority, Egypt and Jordan all agreed in July 2014 that Kerry had ruined the chances of a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. Collaborating with Turkey DEFINITION and Qatar to reach a ceasefire was tantamount to calling the neighbourhood’s pyromaniac instead of the fire department to extinguish the fire. Qatar bankrolls Hamas and Turkey advocates on its behalf. While in Paris in July, Kerry was all smiles Diplomat + with Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu whose boss, Recep Erdogan, recently accused Israel of genocide and compared Netanyahu to Hitler. -

O'hanlon Gordon Indyk

Getting Serious About Iraq 1 Getting Serious About Iraq ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Philip H. Gordon, Martin Indyk and Michael E. O’Hanlon In his 29 January 2002 State of the Union address, US President George W. Bush put the world on notice that the United States would ‘not stand aside as the world’s most dangerous regimes develop the world’s most dangerous weapons’.1 Such statements, repeated since then in various forms by the president and some of his top advisers, have rightly been interpreted as a sign of the administration’s determination to overthrow Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.2 Since the January declaration, however, attempts by the administration to put together a precise plan for Saddam’s overthrow have revealed what experience from previous administrations should have made obvious from the outset: overthrowing Saddam is easier said than done. Bush’s desire to get rid of the Iraqi dictator has so far been frustrated by the inherent difficulties of overthrowing an entrenched regime as well as a series of practical hurdles that conviction alone cannot overcome. The latter include the difficulties of organising the Iraqi opposition, resistance from Arab and European allies, joint chiefs’ concerns about the problems of over-stretched armed forces and intelligence assets and the complications caused by an upsurge in Israeli– Palestinian violence. Certainly, the United States has good reasons to want to get rid of Saddam Hussein. Saddam is a menace who has ordered the invasion of several of his neighbours, killed thousands of Kurds and Iranians with poison gas, turned his own country into a brutal police state and demonstrated an insatiable appetite for weapons of mass destruction. -

Reframing Sacred Values

In Theory Reframing Sacred Values Scott Atran and Robert Axelrod Sacred values differ from material or instrumental values in that they incorporate moral beliefs that drive action in ways dissociated from prospects for success. Across the world, people believe that devotion to essential or core values — such as the welfare of their family and country, or their commitment to religion, honor, and justice — are, or ought to be, absolute and inviolable. Counterintuitively, understanding an opponent’s sacred values, we believe, offers surprising opportunities for breakthroughs to peace. Because of the emotional unwillingness of those in conflict situations to negotiate sacred values, conventional wisdom suggests that nego- tiators should either leave sacred values for last in political negotia- tions or should try to bypass them with sufficient material incentives. Our empirical findings and historical analysis suggest that conven- tional wisdom is wrong.In fact, offering to provide material benefits in exchange for giving up a sacred value actually makes settlement more difficult because people see the offering as an insult rather than a compromise. But we also found that making symbolic concessions of no apparent material benefit might open the way to resolving seem- ingly irresolvable conflicts. Scott Atran is research director in anthropology at CNRS — Institut Jean Nicod in Paris, a presidential scholar in sociology at the John Jay College of the City University of New York, and a visiting professor of psychology and public policy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. His e-mail address is [email protected]. Robert Axelrod is Walgreen Professor for the Study of Human Understanding in the department of political science and in the Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. -

Turkey in Transition: the Dynamics of Domestic and Foreign Politics

EXCERPTED FROM Turkey in Transition: The Dynamics of Domestic and Foreign Politics edited by Gürkan Çelik and Ronald H. Linden Copyright © 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62637-827-8 hc 1800 30th Street, Suite 314 Boulder, CO 80301 USA telephone 303.444.6684 fax 303.444.0824 This excerpt was downloaded from the Lynne Rienner Publishers website www.rienner.com Contents List of Tables and Figures vii Preface ix Turkey at a Glance xi 1 Turkey at a Turbulent Time, Ronald H. Linden and Gürkan Çelik 1 Part 1 Dynamics at Home 2 Domestic Politics in the AKP Era, Gürkan Çelik 19 3 Gains and Strains in the Economy, Gürkan Çelik and Elvan Aktaş 39 4 The Geopolitics of Energy, Mustafa Demir 55 5 Militarization of the Kurdish Issue, Joost Jongerden 69 6 The Diyanet and the Changing Politics of Religion, Nico Landman 81 v vi Contents 7 The Fragmentation of Civil Society, Gürkan Çelik and Paul Dekker 95 8 Women in the “New” Turkey, Jenny White 109 Part 2 Dynamics Abroad 9 Changes and Dangers in Turkey’s World, Ronald H. Linden 125 10 Erdoğan’s Foreign Policy: The Role of Personality and Identity, Henri J. Barkey 147 11 The Crisis in US-Turkish Relations, Aaron Stein 163 12 Turkey in the Middle East, Bill Park 185 13 Russian-Turkish Relations at a Volatile Time, Joris Van Bladel 201 14 Turkey and Europe: Alternative Scenarios, Hanna-Lisa Hauge, Funda Tekin, and Wolfgang Wessels 215 15 Eurocentrism in Migration Policy, Juliette Tolay 231 Part 3 Conclusion 16 Transition to What? Gürkan Çelik and Ronald H. -

OSW COMMENTARY NUMBER 275 1 from the Period of the Late Ottoman Empire1

Centre for Eastern Studies NUMBER 274 | 26.06.2018 www.osw.waw.pl Cadres decide everything – Turkey’s reform of its military Mateusz Chudziak Over the last two years, the Turkish Armed Forces (Türk Silahlı Kuvvetlerı – TSK) have been sub- ject to transformations with no precedent in the history of Turkey as a republic. The process of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) subordinating the army to civilian government has accelerated following the failed coup that took place on 15 July 2016. The government has managed to take away the autonomy of the armed forces which, while retaining their enor- mous significance within the state apparatus, ceased to be the main element consolidating the old Kemalist elites. However, the unprecedented scale of the purges and the introduc- tion of formal civilian control of the military are merely a prelude to a much more profound change intended to create a brand new military, one that would serve the authorities and be composed of a new type of personnel – individuals from outside the army’s traditional power base. This reflects the reshuffle of the elites that happened during AKP’s rule. However, due to the fact that the TSK are a highly complex structure and the political situation both in Turkey itself and in its neighbourhood is tense, the military needs to retain its signif- icance within the state system. Military actions are being carried out in northern Syria and in the south-eastern part of Turkey. In a situation of profound distrust between the political leadership and the military, the government is trying to impact the internal divisions within the TSK by favouring anti-Western, pro-Russian and nationalist groups. -

Beyond Belief: Science, Religion, Reason and Survival the Conversation Continues

Beyond Belief: Science, Religion, Reason and Survival The Conversation Continues Criticism of Beyond Belief by RP Bird It deeply annoys me when the Big Guns of science spout off about protecting science. Like the rest of us have our thumbs up our asses? I'm one of the thousands of Kansans who wrote to the state board of education complaining about the pseudo-science of Intelligent Design. I'm always short of money, but I gave a little to SEA when they started up operations. I've written letters to my state representatives and my congressmen on the subject of science and keeping religious ideas out of science education. So imagine my dismay when I read the NY Times account of the La Jolla meeting. Remember just before the Iraq war, when Middle Eastern experts warned Bush and the rest of us that invading Iraq would be confirmation of the worst fantasies of the jihadist movement? Congratulations, you've just done for science what Bush did for the USA in the Middle East. I can already hear the Christian Right: "We told you, they're out to get us!" Not only that, but you and others want to hurt the cause of science by adopting the methods of the Right? Are you nuts? If you adopt the methods of a religion, you make science into a religion. Also, what's with this "loyalty oath" everyone at the conference had to spout before being heard? No one will listen to them unless they declare the aren't religious? Isn't that what the Christian Right does? You of all people should know that the best defense of science is to do science and teach what you have learned. -

TOWARD the REUNIFICATION of CYPRUS: DEFINING and INTEGRATING RECONCILIATION INTO the PEACE PROCESS Virginie Ladisch

110 Virginie Ladisch 6 TOWARD THE REUNIFICATION OF CYPRUS: DEFINING AND INTEGRATING RECONCILIATION INTO THE PEACE PROCESS Virginie Ladisch In the search for a solution to the “Cyprus problem,” the focus of debate has been on power sharing agreements, land exchanges, right of return, and economics. There has been little focus on reconciliation. This research, conducted one year after the ref- erendum in which Cypriots were given an historic opportunity to vote on the reunifi cation of the island, places the concept of reconciliation at the center of the debate about the Cyprus problem. Based on data gathered through forty interviews with Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot politicians, businessmen, activists, academics, organizational leaders, economists, and members of civil society, this article presents Cypriots’ views on reconciliation. Drawing from literature on reconciliation in confl ict-divided societies as a framework, this article also analyzes the various perceptions Cypriots hold about reconciliation. Finally, this article identifi es initiatives that could be used to promote reconciliation in Cyprus. The process needs to begin immediately so that it can lay the groundwork for the open dialogue, trust building, and understanding that are essential to the successful settlement of the Cyprus problem.1 Virginie Ladisch is a Master in International Affairs candidate at the School of Inter- national and Public Affairs, Columbia University ([email protected]). 7 Toward the Reunifi cation of Cyprus: Defi ning and Integrating Reconciliation into the Peace Process 111 INTRODUCTION In the search for a solution to the “Cyprus problem,” the focus of debates and discussions has been on power sharing agreements, land exchanges, right of return, and economics, but there has been little to no focus on reconciliation. -

The Cost of an Incoherent Foreign Policy

The Cost of an Incoherent Foreign Policy Trump’s Iran Imbroglio Undermines U.S. Priorities Everywhere Else By Brett McGurk BRETT H. McGURK served in senior national security positions under Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump. He is now the Frank E. and Arthur W. Payne Distinguished Lecturer at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute and a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. MORE BY Brett McGurk January 22, 2020 Shortly after taking office, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower gathered senior advisers in the White House solarium to discuss policy toward the Soviet Union. In attendance was his hawkish secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, who had been a vocal critic of Harry Truman’s policy of containment and instead advocated an offensive policy whereby the United States would seek to “roll back” Soviet influence across Europe and Asia. Afternoon light from the southern exposure would have contrasted with the darkening mood inside the White House. Diplomacy to end the Korean War was deadlocked. The United States was entering a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union. Joseph Stalin was dead, but Eisenhower’s calls for dialogue with Moscow had gone unanswered. Defense spending seemed unsustainable. “The Reds today have the better position,” Dulles argued. Containment was proving “fatal” for the West. (Dulles had recently fired career diplomat George Kennan, the author of that policy.) European allies were acting like “shattered old people,” unwilling to face up to Moscow. Eisenhower should break from his predecessor’s shackles, Dulles concluded, and pursue a policy of “boldness” to more directly roll back the communist tide.