Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

(03) ISC Draft Minute Final.Pdf

Item: 3 Page: 6 ABERDEENSHIRE COUNCIL INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES COMMITTEE WOODHILL HOUSE, ABERDEEN, 3 OCTOBER, 2019 Present: Councillors P Argyle (Chair), J Cox (Vice Chair), W Agnew, G Carr, J Gifford (substituting for I Taylor), J Ingram, P Johnston, J Latham, I Mollison, C Pike, G Reid, S Smith, B Topping (substituting for D Aitchison) and R Withey. Apologies: Councillors D Aitchison and I Taylor. Officers: Director of Infrastructure Services, Head of Service (Transportation), Head of Service (Economic Development and Protective Services), Team Manager (Planning and Environment, Chris Ormiston), Team Leader (Planning and Environment, Piers Blaxter), Senior Policy Planner (Ailsa Anderson), Internal Waste Reduction Officer (Economic Development), Corporate Finance Manager (S Donald), Principal Solicitor, Legal and Governance (R O’Hare), Principal Committee Services Officer and Committee Officer (F Brown). OPENING REMARKS BY THE CHAIR The Chair opened the meeting by saying a few words about the weather and recent flooding across the north of Aberdeenshire, which had seen seven bridges closed, with some being destroyed and others extensively damaged. There was also damage to properties, with gardens and driveways being washed away and the Scottish Fire and Rescue being called out to assist with the pumping of water out from homes. Banff, Macduff, Whitehills, St Combs and Crovie were particularly badly hit, along with the King Edward area. The Chair commended the resilience of the local community, with neighbours looking out for one another and businesses starting the clean-up with repairs underway. The closure of seven bridges around King Edward had been particularly challenging and demonstrated the vulnerability of ageing infrastructure which was simply no longer fit for conditions, whether that was the volume and weight of traffic or extreme weather conditions. -

Banffshire, Scotland Fiche and Film

Banffshire Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 Census Maps Probate Records 1861 Census Indexes Miscellaneous Taxes 1881 Census Transcript & Index Monumental Inscriptions Wills 1891 Census Index Non-Conformist Records Directories Parish Registers 1861 CENSUS Banffshire Parishes in the 1861 Census held in the AIGS Library Note that these items are microfilm of the original Census records and are filed in the Film cabinets under their County Abbreviation and Film Number. Please note: (999) number in brackets denotes Parish Number Aberlour (145) Film BAN 145-152 Craigillachie Charleston Alvah (146) Parliamentary Burgh of Banff Royal Burgh of Banff/Banff Town Film BAN 145-152 Macduff (Parish of Gamrie) Macduff Elgin (or Moray) Banff (147) Film BAN 145-152 Banff Landward Botriphnie (148) Film BAN 145-152 Boyndie (149) Film BAN 145-152 Whitehills Cullen (150) Film BAN 145-152 Deskford (151) Kirkton Ardoch Film BAN 145-152 Milltown Bovey Killoch Enzie (152) Film BAN 145-152 Parish of Fordyce (153) Sandend Fordyce Film BAN 153-160 Portsey Parish of Forglen (154) Film BAN 153-160 Parish of Gamrie (155) Gamrie is on Film 145-152 Gardenstoun Crovie Film BAN 153-160 Protstonhill Middletonhill Town of McDuff Glass (199) (incorporated with Aberdeen Portion of parish on Film 198-213) Film BAN 198-213 Parish of Grange (156) Film BAN 153-160 Parish of Inveravon (157) Film BAN 153-160 Updated 18 August 2018 Page 1 of 6 Banffshire Catalogue of Fiche and Film 1861 CENSUS Continued Parish of Inverkeithny (158) Film BAN 153-160 Parish of Keith (159) Old Keith Keith Film BAN 153-160 New Mill Fifekeith Parish of Kirkmichael (160) Film BAN 153-160 Avonside Tomintoul Marnoch (161) Film BAN 161-167 Marnoch Aberchirder Mortlach (162) Film BAN 161-167 Mortlach Dufftown Ordiquhill (163) Film BAN 161-167 Cornhill Rathven (164) Rathven Netherbuckie Lower Shore of Buckie Buckie New Towny Film BAN 161-167 Buckie Upper Shore Burnmouth of Rathven Peterhaugh Porteasie Findochty Bray Head of Porteasie Rothiemay (165) Film BAN 161-167 Milltown Rothiemay St. -

The Fishing-Boat Harbours of Fraserburgh, Sandhaven, Arid Portsoy, on the North-East Coaxt of Scotland.” by JOHNWILLET, M

Prooeedings.1 WILLET ON FRASERBURGH HARBOUR. 123 (Paper No. 2197.) ‘I The Fishing-Boat Harbours of Fraserburgh, Sandhaven, arid Portsoy, on the North-East Coaxt of Scotland.” By JOHNWILLET, M. Inst. C.E. ALONGthe whole line of coast lying between the Firth of Forth and Cromarty Firth, at least 160 miles in length, little natural protection exists for fishing-boats. The remarkable development, however, of the herring-fishery, during the last thirty years, has induced Harbour Boards and owners of private harbours, at several places along the Aberdeenshire and Banffshire coasts, to improve theshelter and increase the accommodation of their harbours, in the design and execution of which works the Author has been engaged for the last twelve years. FIXASERBURGHHARBOUR. Fraserburgh may be regarded as t,he chief Scottish port of the herring-fishery. In 1854, the boats hailing from Fraserburgh during the fishing season were three hundred and eighty-nine, and in 1885 seven hundred and forty-two, valued with their nets and lines atS’255,OOO ; meanwhile the revenue of the harbour increased from 51,743 in 1854 to 59,281 in 1884. The town and harbour are situated on the west side of Fraserburgh Bay, which faces north- north-east, and is about 2 miles longand 1 mile broad. The harbour is sheltered by land, except between north-west and east- south-east. The winds from north round to east bring the heaviest seas into the harbour. The flood-tide sets from Kinnaird Head, at the western extremity of the bay, to Cairnbulg Point at the east, with a velocity of 24 knots an hour ; and the ebb-tide runs in a north-easterly direction from the end of thebreakwater. -

Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Cairnbulg-Whitelinks Bay-St Combs

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Cairnbulg-Whitelinks Bay-St Combs Circuit (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary This is a bracing walk along the windy coastline at the NE corner of Scotland passing through evocative old fishing villages and crossing the wonderful crescent-shaped beach at Whitelinks Bay. Duration: 2.75 hours. Route Overview Duration: 2.75 hours. Transport/Parking: Stagecoach 69 bus service from Fraserburgh. Check timetable. Free parking at walk start/finish, Cairnbulg Harbour. Length: 8.170 km / 5.11 mi Height Gain: 60 meter. Height Loss: 60 meter. Max Height: 16 meter. Min Height: 0 meter. Surface: Moderate. Mostly on paved surfaces. Some walking on good grassy tracks and a section of beach walking. Difficulty: Easy. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance. Dog Friendly: Yes, but keep dogs on lead on public roads. Refreshments: Options in Fraserburgh. Description This is an enjoyable circuit along the airy coast between Cairnbulg and St Combs, on the “Knuckle of North East Scotland”, where the coastline turns west from the more exposed North Sea to the increasingly more sheltered Moray Firth. The combined villages of Cairnbulg and Inverallochy (the local Community Council is now called “Invercairn”) have a long association with the fishing industry, although as the nature of fishing operations changed, the locus moved to nearby Fraserburgh. The inadequate nature of the original fisher huts was cruelly exposed in the cholera epidemics of the 1860s and they were cleared to make way for planned settlements centred on Inverallochy and Cairnbulg and, a little further down the coast, at St Combs. -

Cairn of Memsie Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC231 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90216) Taken into State care: 1930 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE CAIRN OF MEMSIE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH CAIRN OF MEMSIE BRIEF DESCRIPTION The Cairn of Memsie stands about 4.5km SSW of Fraserburgh in agricultural land. It is a splendid and well-preserved example of a large round burial cairn built in latter half of the 3rd millennium BC, and was once accompanied by two other large burial cairns and many smaller cairns. -

The Dalradian Rocks of the North-East Grampian Highlands of Scotland

Revised Manuscript 8/7/12 Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian 6 7 Highlands of Scotland 8 9 D. Stephenson, J.R. Mendum, D.J. Fettes, C.G. Smith, D. Gould, 10 11 P.W.G. Tanner and R.A. Smith 12 13 * David Stephenson British Geological Survey, Murchison House, 14 West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 15 [email protected] 16 0131 650 0323 17 John R. Mendum British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 18 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 19 Douglas J. Fettes British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 20 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 21 C. Graham Smith Border Geo-Science, 1 Caplaw Way, Penicuik, 22 Midlothian EH26 9JE; formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 23 David Gould formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 24 P.W. Geoff Tanner Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences, 25 University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow 26 27 G12 8QQ. 28 Richard A. Smith formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 29 30 * Corresponding author 31 32 Keywords: 33 Geological Conservation Review 34 North-east Grampian Highlands 35 Dalradian Supergroup 36 Lithostratigraphy 37 Structural geology 38 Metamorphism 39 40 41 ABSTRACT 42 43 The North-east Grampian Highlands, as described here, are bounded 44 to the north-west by the Grampian Group outcrop of the Northern 45 Grampian Highlands and to the south by the Southern Highland Group 46 outcrop in the Highland Border region. The Dalradian succession 47 therefore encompasses the whole of the Appin and Argyll groups, but 48 also includes an extensive outlier of Southern Highland Group 49 strata in the north of the region. -

Banffshire and Buchan Coast Polling Scheme

Polling Station Number Constituency Polling Place Name Polling Place Address Polling District Code Ballot Box Number Eligible electors Vote in person Vote by post BBC01 Banffshire and Buchan Coast DESTINY CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HALL THE SQUARE, PORTSOY, BANFF, AB45 2NX BB0101 BBC01 1342 987 355 BBC02 Banffshire and Buchan Coast FORDYCE COMMUNITY HALL EAST CHURCH STREET, FORDYCE, BANFF, AB45 2SL BB0102 BBC02 642 471 171 BBC03 Banffshire and Buchan Coast WHITEHILLS PUBLIC HALL 4 REIDHAVEN STREET, WHITEHILLS, BANFF, AB45 2NJ BB0103 BBC03 1239 1005 234 BBC04 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ST MARY'S HALL BANFF PARISH CHURCH, HIGH STREET, BANFF, AB45 1AE BBC04 BBC05 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ST MARY'S HALL BANFF PARISH CHURCH, HIGH STREET, BANFF, AB45 1AE BBC05 BBC06 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ST MARY'S HALL BANFF PARISH CHURCH, HIGH STREET, BANFF, AB45 1AE BB0104 BBC06 3230 2478 752 BBC07 Banffshire and Buchan Coast WRI HALL HILTON HILTON CROSSROADS, BANFF, AB45 3AQ BB0105 BBC07 376 292 84 BBC08 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ALVAH PARISH HALL LINHEAD, ALVAH, BANFF, AB45 3XB BB0106 BBC08 188 141 47 BBC09 Banffshire and Buchan Coast HAY MEMORIAL HALL 19 MID STREET, CORNHILL, BANFF, AB45 2ES BB0107 BBC09 214 169 45 BBC10 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ABERCHIRDER COMMUNITY PAVILION PARKVIEW, ABERCHIRDER, AB54 7SW BBC10 BBC11 Banffshire and Buchan Coast ABERCHIRDER COMMUNITY PAVILION PARKVIEW, ABERCHIRDER, AB54 7SW BB0108 BBC11 1466 1163 303 BBC12 Banffshire and Buchan Coast FORGLEN PARISH CHURCH HALL FORGLEN, TURRIFF, AB53 4JL BB0109 BBC12 250 216 34 -

Ritchie Road

Ritchie Road 5 Rosehearty, Fraserburgh, AB43 7NY Ritchie Road 5 Rosehearty, Fraserburgh, AB43 7NY Located within the coastal village of Rosehearty, we are delighted to offer to the market this substantial five bedroom executive detached family dwelling house situated on a large plot with fabulous views over the sea. The property was architecturally designed in 1997 and built by the current owners in 1998 with quality fixtures and fittings throughout. The property would serve as an excellent family home as it is located in a safe and quiet cul-de-sac. The accommodation comprises:- The ground floor: An expansive reception hallway providing access to the staircase with a large walk in cupboard below as well as an additional storage cupboard. A well proportioned lounge with bay window is currently being used as a games room. There is also a bright and airy sun room with 180 degree views overlooking the garden with excellent sea views with French doors leading outside. The ground floor bathroom has split level four piece bathroom suit comprises of corner bath, single shower cubicle with mains shower over, and wash hand basin and WC. Open plan dining kitchen, dining room and family room. The kitchen has large bay windows overlooking the rear garden and sea and is fitted with solid wood base and wall mounted units with complimenting worktops, sink and tiled splashback. Integrated ceramic hob with extractor hood, double oven and American fridge freezer. Large dining area leading to the family area with patio doors leading to the rear garden. The utility room is fitted with cream base and wall mounted units, stainless steel sink, under counter washing machine and tumble dryer, external door to the garden and door providing access to the double garage. -

Banff Castle

UE 12 2010 - ISS insideinside thisthis issueissue .. .. .. newsnews fromfrom aroundaround thethe areaarea .. .. .. TransportTransport newsnews .. .. .. andand lotslots moremore partnershipupdate Chairman’s Letter Design: Kay Beaton, elcome to the latest edition of the Banffshire Partnership PURPLEcreativedesign WNewsletter. During the year one of the longest serving directors Eddie Bruce Printed by had to stand down due to ill-health. Eddie was a very valued Halcon, Aberdeen member of the board and I would like to record our thanks for community transport Paper his contribution and wise counsel over the years. Printed on environ- Also during the year Evelyn Elphinstone, our administrator and book-keeper retired. Evelyn had worked for the Partnership for many mentally friendly paper. years and I would also like to record our thanks for her hard work and Woodpulp sourced from dedication over the years. sustainable forests. This has been a busy and challenging year for BPL. Once again we entered into a formal Service Level Agreement with Aberdeenshire Council which commenced on 1st April and Board Of Directors runs to 31st March 2010. This is core funding for the Partnership which allows it to carry Directors can be out its very important tasks helping many community groups throughout our operational “keeping the community moving” area. contacted through the With the expected squeeze on local government finances in the coming years there Partnership is no guarantee that such funding will endure at the required level. However, both community use minibus office - 01261 843286. Aberdeenshire Council and the Local Rural Partnerships across the shire are keen to ensure that they survive any reduced funding from the Scottish Government. -

Cottonhill Quarry to Bodychell Quarry

The institute of quarrying Quarry Trails SCOTLAND | ENGLAND | WALES | N.Ireland The Institute of Quarrying From Cottonhill Quarry to Bodychell Quarry Approximate journey time: 1 hourS 41 MINUTES Distance: 20.2 miles QuarrIES Fact file: Address: Address: Macduff, Banff, Aberdeenshire Memsie, Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire, AB43 7DB (57.664583° -2.4642653°) (57.659841° -2.0805119°) Operator Name: Operator Name: Lovie Ltd Lovie Ltd Planning Region: Planning Region: Scotland Scotland Commodity Produce: Commodity Produce: Igneous & Metamorphic Rock Sand & Gravel lithostratigraphy: lithostratigraphy: Macduff Formation (Macduff Slates) Glaciofluvial Sheet Deposits Age: Age: Neoproterozoic Quaternary www.quarrying.org The Institute of Quarrying Route planner Distance to directions travel Start at Cottonhill Quarry Macduff, Banff, Aberdeenshire 0.0 mi (57.664583° -2.4642653°) 0.2 mi Head south-west towards B9031 0.8 mi Turn left onto B9031 0.7 mi Turn right 17.9 mi Turn left onto A98 0.7 mi Turn right onto B9032 Arrive at Bodychell Quarry Memsie, Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire, AB43 7DB 0.0 mi (57.659841° -2.0805119°) www.quarrying.org The Institute of Quarrying Safety Advice Please ensure you do not enter onto any quarry site. Ensure follow all road markings and are aware of your surroundings. Wear appropriate clothing and be prepared for changing weather conditions. Only undertake the route if it is within your cycling and fitness capability and ensure you schedule in refreshment breaks in along the way. Check all of your equipment is in good condition. Environmental conditions can change the nature of the trails within a short space of time, you should only continue if safe to do so. -

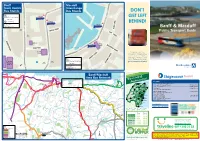

Banff and Macduff Public Transport Guide October 2015

Banff_Town_Centre_Map.ai 1 16/10/2015 11:44 Macduff_Town_Centre_Map.ai 1 16/10/2015 11:43 Banff BOYNDIE STREET Macduff Town©P1ndar Centre ©P1ndar © Interchange©P1ndar ©P1ndar © Bus Stands Bus Stands REET DON’T CARMELITE STREET T S S Key A S E Low Street ©P1ndar Road served by bus B9142 LOW STREE GET LEFT O’N A98 HIGH STREET Bus stop K B E Car parking ©P1ndar Low Street N CROO BEHIND! A Don’t get left behind Contains Ordnance Survey data LA Nicols Brae ©P1ndar © Crown copyright 2015 L i Digital Cartography by Pindar Creative www.pindarcreative.co.uk©P1ndar ©P1ndar © ©P1ndar ©P1ndar © HOO Banff & Macduff SC High T Street ©P1ndar BRIDGE STREET DUF Public Transport Guide F 8 S 9 TREET High A ©P1ndar Street October 2015 WALKER AVENUE Library ©P1ndar B Town Town Hall I ©P1ndar ©P1ndar © ©P1ndar ©P1ndarHall NST © IT UT ©P1ndar I To receive advanced notification of changes to BACK PATH Hutcheon Street ON STREET S bus services in Aberdeenshire by email, E TR sign up for our free alert service at OR EE Court SH T www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/publictransport/status/ EET To receive advanced House R T We are currently in the process of ET notificationequipping of all buschanges stops in to bus S Aberdeenshire with QR Codes and NFC Technology. TRE services in Aberdeenshire by W This will allow you to look up bus S times from your stop for free* in O seconds using your Smartphone. L L email, sign up for our free alert CHURCH STREET L Look for symbols like these Key I service at www.aberdeenshire.at the bus stop Just scan the top QR Code, or if you Airlie Road served by bus LLYM have a smartphone equipped with NFC gov.uk/publictransport/status/technology, hold it against the indicated Banff ©P1ndar E 9142 Gardens Airlie G area to take you to a page showing B the departure times from your stop.