Mangione-Produced-Docs-4.23.2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the District Court of Appeal of Florida Fifth District

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF FLORIDA FIFTH DISTRICT CASE NO. 5D14-2951 L.T. NO.: 2013-CA-2664-0 KNIGHT NEWS, INC., Appellant, v. THE UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA BOARD OF TRUSTEES and JOHN C. HITT, Appellees. ON REVIEW FROM THE NINTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT IN AND FOR ORANGE COUNTY, FLORIDA BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE STUDENT PRESS LAW CENTER, FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION, FLORIDA PRESS ASSOCIATION, REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS, AND WKMG-TV IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT Carol Jean LoCicero (FBN 603030) RECEIVED, 3/16/2015 2:49 PM, Pamela R. Masters, Fifth District Court of Appeal [email protected] Mark R. Caramanica (FBN 110581) [email protected] THOMAS & LOCICERO PL 601 South Boulevard Tampa, FL 33606 Tel.: (813) 984-3060 Fax: (813) 984-3070 Attorneys for Amici Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................... ii IDENTITY OF AMICI CURIAE AND STATEMENT OF INTEREST ................... l SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................................................................. 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................. 4 A. Access to public records from colleges and schools is essential for honest, accountable government ..................................................................... 4 B. Colleges and schools habitually misuse FERP A to conceal records even where no legitimate student privacy interest exists ................................ 6 -

Lexisnexis® Smartindexing Technology™

LexisNexis ® SmartIndexing Technology ™ Industry & Subject Terms Alphabetical Listing Table of Contents Page 0-9 - A 2 B 7 C 10 D 18 E 20 F 24 G 28 H 30 I 32 J - K 35 L 36 M 38 N 44 O 45 P 47 Q - R 53 S 61 T 55 U 66 V 67 W 68 X - Y - Z 70 1/09/2012 Copyright © 2010 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc All rights reserved. 1 LexisNexis ® SmartIndexing Technology ™ Industry & Subject Terms Alphabetical Listing 0-9 – A ACQUISITIONS ACQUITTAL 2008 GLOBAL FOOD CRISIS ACTION & ADVENTURE FILMS 2010 GULF COAST OIL SPILL ACTORS & ACTRESSES 2010 ICELANDIC VOLCANO ERUPTION ACTUARIAL SERVICES 2010 PAKISTAN FLOODS ACUTE CARE 2010 POLISH PLANE CRASH ACUTE RADIATION SYNDROME 2010 VANCOUVER WINTER OLYMPICS ADEQUATE YEARLY PROGRESS 2010 WALL STREET & BANKING REFORM ADHESIVES & SEALANTS 2010 WEST VIRGINIA COAL MINE EXPLOSION ADHESIVES & SEALANTS MFG 2011 EGYPTIAN PROTESTS ADMINISTRATIVE LAW 2011 LIBYAN UPRISING ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGES 2011 PENN STATE SEX ABUSE SCANDAL ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE 2011 TUCSON SHOOTING ADMINISTRATIVE SUPPORT SERVICES 2012 LONDON SUMMER OLYMPICS ADMIRALTY LAW 3G WIRELESS ADMISSION TO PRACTICE LAW 401K PLANS ADMISSIONS & CONFESSIONS 4G WIRELESS ADOLESCENTS ABORTION ADOPTION ABRASIVE PRODUCT MFG ADOPTION LAW ACADEMIC ADMISSIONS ADOPTION SERVICES ACADEMIC FREEDOM ADULT DAY CARE ACADEMIC LIBRARIES ADULT PROTECTIVE SERVICES ACADEMIC STANDARDS ADVANCED PLACEMENT PROGRAMS ACADEMIC STANDARDS & TESTING ADVERSE DRUG EVENT REPORTING ACADEMIC TENURE ADVERTISING ACCOUNTS IN REVIEW ACADEMIC TESTING ADVERTISING COPY TESTING ACCIDENT -

Ebooks-Civil Cover Sheet

, J:a 44C/SDNY COVE ~/21112 REV: CiV,L: i'l2 CW r 6·· .,.. The JS44 civil cover sheet and the information contained herein neither replace nor supplement the fiOm ic G) pleadings or other papers as required by law, except as provided by local rules of court. This form, approved IJ~ JUdicial Conference of the United Slates in September 1974, is required for use of the Clerk of Court for the purpose of 5 initiating the civil docket sheet. ~=:--- -:::-=:-:::-:-:-:~ ~AUG 292012 PLAINTIFFS DEFENDANTS State of Texas, State of Connecticut, State of Ohio, et. al (see attached Hachette Book Group, Inc; HarperCollins Publishers, LLC; Simon & Schuster, sheets for Additional Plaintiffs) Inc; and Simon & Schuster Digital Sales, Inc. ATIORNEYS (FIRM NAME, ADDRESS, AND TELEPHONE NUMBER ATIORNEYS (IF KNOWN) Rebecca Fisher, TX Att-j Gan.Off. P.O.Box 12548. Austin TX 78711-12548, Paul Yde. Freshflelds, 701 Pennsylvania Ave., NW, Washington D.C. 20004 512463-1265: (See attached sheets for additional Plaintiff Attomey contact 2692: Clifford Aronson, Skadden Arps, 4 Times Sq., NY, NY 10036-6522; information) Helene Jaffe, Prosknuer Rose,LLP, Eleven Times Square, NY, NY 10036 CAUSE OF ACTION (CITE THE U.S. CIVIL STATUTE UNDER WHICH YOU ARE FILING AND WRITE A BRIEF STATEMENT OF CAUSE) (DO NOT CITE JURISDICTIONAL STATUTES UNLESS DIVERSITY) 15 USC §1 and 15 USC §§15c & 26. Plaintiffs allege Defendants entered illegal contracts and conspiracies in restraint of trade for e-books. Has this or a similar case been previously filed in SONY at any time? No 0 Yes 0 Judge Previously Assigned Judge Denise Cote If yes, was lhis case Vol. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 11-564 In the Supreme Court of the United States FLORIDA , Petitioner , v. JOELIS JARDINES , Respondent . On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida BRIEF OF TEXAS , ALABAMA , ARIZONA , COLORADO , DELAWARE , GUAM , HAWAII , IDAHO , IOWA , KANSAS , KENTUCKY , LOUISIANA , MICHIGAN , NEBRASKA , NEW MEXICO , TENNESSEE , UTAH , VERMONT , AND VIRGINIA AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER GREG ABBOTT ADAM W. ASTON Attorney General of Assistant Solicitor Texas General Counsel of Record DANIEL T. HODGE First Assistant Attorney OFFICE OF THE General ATTORNEY GENERAL P.O. Box 12548 DON CLEMMER Austin, Texas 78711-2548 Deputy Attorney General [Tel.] (512) 936-0596 for Criminal Justice [email protected] JONATHAN F. MITCHELL Solicitor General COUNSEL FOR AMICI CURIAE [Additional counsel listed on inside cover] ADDITIONAL COUNSEL LUTHER STRANGE Attorney General of Alabama TOM HORNE Attorney General of Arizona JOHN W. SUTHERS Attorney General of Colorado JOSEPH R. BIDEN, III Attorney General of Delaware LEONARDO M. RAPADAS Attorney General of Guam DAVID M. LOUIE Attorney General of Hawaii LAWRENCE G. WASDEN Attorney General of Idaho ERIC J. TABOR Attorney General of Iowa DEREK SCHMIDT Attorney General of Kansas JACK CONWAY Attorney General of Kentucky JAMES D. “BUDDY” CALDWELL Attorney General of Louisiana BILL SCHUETTE Attorney General of Michigan JON BRUNING Attorney General of Nebraska GARY KING Attorney General of New Mexico ROBERT E. COOPER, JR. Attorney General of Tennessee MARK L. SHURTLEFF Attorney General of Utah WILLIAM H. SORRELL Attorney General of Vermont KENNETH T. CUCCINELLI, II Attorney General of Virginia i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities ........................ -

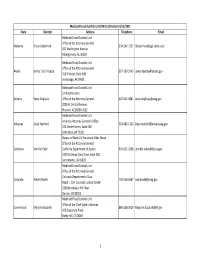

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021

Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alabama Bruce Lieberman 334‐242‐7327 [email protected] 501 Washington Avenue Montgomery, AL 36130 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Alaska James "Jay" Fayette 907‐269‐5140 [email protected] 310 K Street, Suite 308 Anchorage, AK 99501 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Criminal Division Arizona Steve Duplissis Office of the Attorney General 602‐542‐3881 [email protected] 2005 N. Central Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85004‐1592 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Arkansas Attorney General's Office Arkansas Lloyd Warford 501‐682‐1320 [email protected] 323 Center Street, Suite 200 Little Rock, AR 72201 Bureau of Medi‐Cal Fraud and Elder Abuse Office of the Attorney General California Jennifer Euler California Department of Justice 916‐621‐1858 [email protected] 2329 Gateway Oaks Drive, Suite 200 Sacramento, CA 95833 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Colorado Department of Law Colorado Robert Booth 720‐508‐6687 [email protected] Ralph L. Carr Colorado Judicial Center 1300 Broadway, 9th Floor Denver, CO 80203 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Chief State's Attorney Connecticut Marjorie Sozanski 860‐258‐5929 [email protected] 300 Corporate Place Rocky Hill, CT 06067 1 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU) Directors 4/15/2021 State Director Address Telephone Email Medicaid Fraud Control Unit Office of the Attorney General Delaware Edward Black (Acting) 302‐577‐4209 [email protected] 820 N French Street, 5th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Medicaid Fraud Control Unit District of Office of D.C. -

Jena M. Griswold Colorado Secretary of State

Jena M. Griswold Colorado Secretary of State July 28, 2020 Senator Mitch McConnell Senator Charles E. Schumer Senator Richard C. Shelby Senator Patrick J. Leahy Senator Roy Blunt Senator Amy Klobuchar Dear Senators: As Secretaries of State of both major political parties who oversee the election systems of our respective states, we write in strong support of additional federal funding to enable the smooth and safe administration of elections in 2020. The stakes are high. And time is short. The COVID-19 pandemic is testing our democracy. A number of states have faced challenges during recent primary elections. Local administrators were sometimes overwhelmed by logistical problems such as huge volumes of last-minute absentee ballot applications, unexpected shortages of poll workers, and difficulty of procuring and distributing supplies. As we anticipate significantly higher voter turnout in the November General Election, we believe those kinds of problems could be even larger. The challenge we face is to ensure that voters and our election workers can safely participate in the election process. While none of us knows what the world will look like on November 3rd, the most responsible posture is to hope for the best and plan for the worst. The plans in each of our states depend on adequate resources. While we are truly grateful for the resources that Congress made available in the CARES Act for election administration, more funding is critical. Current funding levels help to offset, but do not cover, the unexpectedly high costs that state and local governments face in trying to administer safe and secure elections this year. -

Brief of Petitioner for Howes V. Fields, 10-680

No. 10-680 In the Supreme Court of the United States ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ CAROL HOWES, Petitioner, v. RANDALL FIELDS, Respondent. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE OF OHIO, ALABAMA, ALASKA, ARIZONA, ARKANSAS, COLORADO, DELAWARE, FLORIDA, GUAM, HAWAII, IDAHO, ILLINOIS, INDIANA, IOWA, KANSAS, KENTUCKY, LOUISIANA, MAINE, MARYLAND, MONTANA, NEBRASKA, NEVADA, NEW HAMPSHIRE, NEW MEXICO, NORTH DAKOTA, PENNSYLVANIA, SOUTH CAROLINA, SOUTH DAKOTA, TENNESSEE, TEXAS, UTAH, VERMONT, VIRGINIA, WASHINGTON, WISCONSIN, AND WYOMING IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ MICHAEL DEWINE Attorney General of Ohio ALEXANDRA T. SCHIMMER* Solicitor General *Counsel of Record DAVID M. LIEBERMAN Deputy Solicitor 30 East Broad St., 17th Floor Columbus, Ohio 43215 614-466-8980 Counsel for Amici Curiae LUTHER STRANGE LISA MADIGAN Attorney General Attorney General State of Alabama State of Illinois JOHN J. BURNS GREGORY F. ZOELLER Attorney General Attorney General State of Alaska State of Indiana TOM HORNE TOM MILLER Attorney General Attorney General State of Arizona State of Iowa DUSTIN MCDANIEL DEREK SCHMIDT Attorney General Attorney -

VAWA”) Has Shined a Bright Light on Domestic Violence, Bringing the Issue out of the Shadows and Into the Forefront of Our Efforts to Protect Women and Families

January 11, 2012 Dear Members of Congress, Since its passage in 1994, the Violence Against Women Act (“VAWA”) has shined a bright light on domestic violence, bringing the issue out of the shadows and into the forefront of our efforts to protect women and families. VAWA transformed the response to domestic violence at the local, state and federal level. Its successes have been dramatic, with the annual incidence of domestic violence falling by more than 50 percent1. Even though the advancements made since in 1994 have been significant, a tremendous amount of work remains and we believe it is critical that the Congress reauthorize VAWA. Every day in this country, abusive husbands or partners kill three women, and for every victim killed, there are nine more who narrowly escape that fate2. We see this realized in our home states every day. Earlier this year in Delaware, three children – ages 12, 2 ½ and 1 ½ − watched their mother be beaten to death by her ex-boyfriend on a sidewalk. In Maine last summer, an abusive husband subject to a protective order murdered his wife and two young children before taking his own life. Reauthorizing VAWA will send a clear message that this country does not tolerate violence against women and show Congress’ commitment to reducing domestic violence, protecting women from sexual assault and securing justice for victims. VAWA reauthorization will continue critical support for victim services and target three key areas where data shows we must focus our efforts in order to have the greatest impact: • Domestic violence, dating violence, and sexual assault are most prevalent among young women aged 16-24, with studies showing that youth attitudes are still largely tolerant of violence, and that women abused in adolescence are more likely to be abused again as adults. -

March 7, 2019 Ms. Eva Guidarini U.S. Politics & Government Outreach

NASS EXECUTIVE BOARD Hon. Jim Condos, VT President March 7, 2019 Hon. Paul Pate, IA Ms. Eva Guidarini President-elect U.S. Politics & Government Outreach, Facebook Hon. Maggie Toulouse Oliver, NM 575 7th Street NW Treasurer Washington, D.C. 20004 Hon. Steve Simon, MN Secretary Dear Ms. Guidarini: Hon. Connie Lawson, IN Immediate Past President On behalf of the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS), I would like to thank you for your willingness to work with the Secretaries Hon. Denise Merrill, CT Eastern Region Vice President of State, election directors and other important stakeholders to address misinformation and disinformation on your platforms related to the Hon. Tre Hargett, TN elections process. We believe significant progress has been made to Southern Region Vice President understand and address these issues. As we move into 2019 and the 2020 Hon. Jay Ashcroft, MO general election, we urge Facebook to further engage on the following Midwestern Region Vice President issues: Hon. Alex Padilla, CA Western Region Vice President First, the elections community faced many challenges as a result of Facebook’s use of a non-government, third-party site to prompt Hon. Al Jaeger, ND Member-at-Large (NPA) users to register to vote. We instead encourage Facebook to either connect directly to the chief state election webpages, state online voter Hon. Matt Dunlap, ME registration system webpages, and/or vote.gov. These government- Member -at-Large (ACR) backed websites will provide accurate information to the public, eliminating confusion and frustration in the voter registration process. As we have previously discussed, in the 2018 midterm election cycle, a non- government, third-party site failed to properly notify users of incomplete voter registration applications initiated through their site. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2019 No. 206 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, House amendment to the Senate called to order by the Honorable THOM PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, amendment), to change the enactment TILLIS, a Senator from the State of Washington, DC, December 19, 2019. date. North Carolina. To the Senate: McConnell Amendment No. 1259 (to Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, Amendment No. 1258), of a perfecting f of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby appoint the Honorable THOM TILLIS, a Sen- nature. McConnell motion to refer the mes- PRAYER ator from the State of North Carolina, to perform the duties of the Chair. sage of the House on the bill to the The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- CHUCK GRASSLEY, Committee on Appropriations, with in- fered the following prayer: President pro tempore. structions, McConnell Amendment No. Let us pray. Mr. TILLIS thereupon assumed the 1260, to change the enactment date. Eternal God, You are our light and Chair as Acting President pro tempore. McConnell Amendment No. 1261 (the salvation, and we are not afraid. You instructions (Amendment No. 1260) of f protect us from danger so we do not the motion to refer), of a perfecting na- tremble. RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME ture. Mighty God, You are not intimidated The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- McConnell Amendment No. 1262 (to by the challenges that confront our Na- pore. -

Social Policy and the American Welfare State

CHAPTER 1 Social Policy and the American Welfare State Source: The Image Works 1 M01_KARG8973_7E_SE_C01.indd 1 12/5/12 11:45 AM 2 PART 1 American Social Welfare Policy ocial welfare policy is best viewed through would restrain Obama’s ambitions. Massive deficits Sthe lens of political economy (i.e., the interac- left by the Bush administration, compounded by a tion of economic, political, and ideological forces). severe global financial crisis and two unfunded wars, This chapter provides an overview of the Ameri- meant that economic issues would trump other pri- can welfare state through that lens. In particular, it orities. Reduced tax revenues would impede the examines various definitions of social welfare policy, ability of the government to meet existing obliga- the relationship between social policy and social tions, let alone expand social programs. Obama’s problems, and the values and ideologies that drive centrist inclinations to build bipartisan support for social welfare in the United States. In addition, the his legislative agenda failed as newly elected extrem- chapter examines the effects of ideology on the U.S. ist Tea Party legislators squashed most of his at- welfare state, including the important roles played tempts at compromise. Instead, ideologically driven by conservatism and liberalism (and their varia- legislators focused on social issues such as abor- tions) in shaping welfare policy. An understand- tion, and even resuscitated the previously long-dead ing of social welfare policy requires the ability to issue of contraception. Parts of the nation had not grasp the economic justifications and consequences just turned right, but hard right. -

Resolution Reaffirming the NASS Position on Funding and Authorization of the U.S

Resolution Reaffirming the NASS Position on Funding and Authorization of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission WHEREAS, the National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS), on February 6, 2005, voted to approve a resolution by a substantial majority asking Congress not to reauthorize or fund the U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) after the conclusion of the 2006 federal election, by which date all the states were required to fully implement the mandates of the Help America Vote Act; and WHEREAS, the 2005 resolution was passed to help prevent the EAC from eventually evolving into a regulatory body, contrary to the spirt of the Help America Vote Act; and WHEREAS, that action was meant to preserve the state’ ability to serve as laboratories of change through successful experiments and innovation in election reform; and WHEREAS, each resolution passed at a NASS conference sunsets after five years unless reauthorized by a vote of the members; and WHEREAS, the NASS position on funding and authorization of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission was renewed by the membership on July 20, 2010; NOW THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED that the National Association of Secretaries of State, expressing their continued consistent position in 2015, reaffirm their resolution of 2005 and 2010 and encourage Congress not to reauthorize or fund the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. Adopted the 12th day of July 2015 in Portland, ME EXPIRES: Summer 2020 Hall of States, 444 N. Capitol Street, N.W., Suite 401, Washington, DC 20001 (202) 624-3525 Phone (202) 624.3527 Fax www.nass.org On the motion to adopt the Resolution Reaffirming the NASS Position on Funding and Authorization of the U.S.