War Crimes Prosecution Watch, Vol. 15, Issue 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint Were and S: 25 of the District Detained

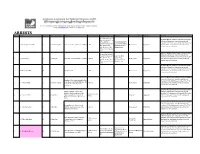

Current No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Address Remark Condition Superintendent Myanmar Military Seizes Power Kyi Lin of and Senior NLD leaders S: 8 of the Export Special Branch, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint were and S: 25 of the District detained. The NLD’s chief Natural Disaster Administrator ministers and ministers in the Management law, (S: 8 and 67), states and regions were also 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Penal Code - Superintendent House Arrest Naypyitaw detained. 505(B), S: 67 of Myint Naing Arrested State Counselor Aung the (S: 25), U Soe San Suu Kyi has been charged in Telecommunicatio Soe Shwe (S: Rangoon on March 25 under ns Law, Official 505 –b), Section 3 of the Official Secrets Secret Act S:3 Superintendent Act. Aung Myo Lwin (S: 3) Myanmar Military Seizes Power S: 25 of the and Senior NLD leaders Natural Disaster including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Superintendent Management law, and President U Win Myint were Myint Naing, Penal Code - detained. The NLD’s chief 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Dekkhina House Arrest Naypyitaw 505(B), S: 67 of ministers and ministers in the District the states and regions were also Administrator Telecommunicatio detained. ns Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. -

The CIA Rigged Foreign Spy Devices for Years. What Secrets Should It Share

The CIA rigged foreign spy devices for years. What secrets shouldnow/2020/02/28/b570a4ea-58ce-11ea-9000-f3cffee23036_story.html it share now? By Peter Kornbluh/ senior analyst at the National Security Archive, a nonprofit research center in Washington that advocates for declassification and freedom of information/ Twitter: @peterkornbluh February 28, 2020 The revelation that the CIA secretly co-owned the world’s leading manufacturer of encryption machines, and rigged those devices to conduct espionage on more than 100 nations that purchased them for more than half a century, has generated a number of historical and ethical questions: What did U.S. officials know, and when did they know it, about key episodes in recent world history? How did U.S. policymakers act on the intelligence that was gathered? Did U.S. officials have an obligation, as The Washington Post’s Greg Miller put it, to “expose or stop human rights violations unfolding in their view”? Should the United States have been spying on friends and foes alike? But the most immediate question has yet to be answered: What should the United States do with the massive trove of intercepted communications it obtained and decrypted, along with the thousands of secret intelligence reports those intercepts generated? Those files are gathering dust in the SCIFs — the sensitive compartmented information facilities — of the CIA and the National Security Agency. Hidden away, the documents represent a history held hostage; they have the potential to significantly advance the historical record, not only on U.S. foreign policy but on key world crises and events (wars, coups, terrorist attacks, peace accords) over more than five decades. -

Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 1-26-1996 Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation." (1996). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/12109 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 55802 ISSN: 1060-4189 Arrest of Suspected Assassin Yields New Demands for Pinochet Resignation by LADB Staff Category/Department: Chile Published: 1996-01-26 In mid-January, police in Argentina arrested the person believed responsible for the 1974 assassination in Buenos Aires of Chilean Gen. Carlos Prats and his wife Sofia Couthbert. The individual arrested is a former Chilean intelligence agent, and his capture has brought renewed calls for the resignation of Chile's army chief, Gen. Augusto Pinochet. The case has also resurfaced tensions between the Chilean military and the civilian government of President Eduardo Frei. On Jan. 19, Argentine police in Buenos Aires arrested Enrique Lautaro Arancibia Clavel, a Chilean citizen who is suspected of being the intellectual author of the 1974 assassination of Gen. Prats and his wife. The arrest was announced by Argentine President Carlos Saul Menem, who called it "a new victory for justice and for the federal police." Police sources said Arancibia Clavel had been sought for years by Argentine, Chilean, and Italian authorities in connection with the deaths of Prats and his wife, as well as for carrying out other assassinations on behalf of the Chilean secret service (Direccion de Inteligencia Nacional, DINA). -

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Hagelin) by Williaj-1 F

.. REF ID :A2436259 Declassified and approved for release by NSA on 07-22 2014 pursuant to E.O. 1352e REF ID:A2436259 '!'UP SECRE'l' REPORT"OF.VISIT 1Q. CRYPTO A.G. (HAGELIN) BY WILLIAJ-1 F. FRIEDI.W.if SPECIAL ASSISTANT TO THE DIRECTOR, NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY 21 - 28 FEBRUARY 1955 ------------------ I -:-· INTRO:bUCTIOI~ 1. In accordance with Letter Orders 273 dated 27 January 1955, as modified by L.0.273-A dated~ February 1955, I left Washington via MATS at 1500 houri' on 18 'February 1955, arrived at Orly Field, Pe,ris, at 1430 hours on 19 February, ' • • f • I ' -,-:--,I." -'\ iII ~ ~ ,.oo4 • ,. ,.. \ • .... a .. ''I •:,., I I .arid at Zug, Switzerland, at 1830 the same day. I sp~~~ th~· ~e~t .few da;s· ~ Boris Hagelin, Junior, for the purpose of learning the status of their new deyelop- ' ments in crypto-apparatus and of makifie an approach and a proposal to Mr. Hagelin S~, 1 / as was recently authorized by.USCIB and concurred in by LSIB. ~ Upon completion of that part of my mission, I left Zug at 1400 hours on ··'··· 28 February and proceeded by atrb-eme:Bfle to Zll:N:ch, ·1.'fteu~ I l3e-a.d:ee: a s~f3:es ah3::i:nMP plE.t;i~ie to London, arriving i:n mndo-l't' at 1845 that evening, f;the schedu1 ed p1anli ed 2_. The following report is based upon notes made of the subste.nce of several talks with the Hagel~ns, at times in separate meetings with each of them and at other times in meetings with both of them. -

The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2008 The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976 Emily R. Steffan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Steffan, Emily R., "The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976" (2008). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1235 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emily Steffan The United States' Janus-Faced Approach To Operation Condor: Implications For The Southern Cone in 1976 Emily Steffan Honors Senior Project 5 May 2008 1 Martin Almada, a prominent educator and outspoken critic of the repressive regime of President Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, was arrested at his home in 1974 by the Paraguayan secret police and disappeared for the next three years. He was charged with being a "terrorist" and a communist sympathizer and was brutally tortured and imprisoned in a concentration camp.l During one of his most brutal torture sessions, his torturers telephoned his 33-year-old wife and made her listen to her husband's agonizing screams. -

0714685003.Pdf

CONTENTS Foreword xi Acknowledgements xiv Acronyms xviii Introduction 1 1 A terrorist attack in Italy 3 2 A scandal shocks Western Europe 15 3 The silence of NATO, CIA and MI6 25 4 The secret war in Great Britain 38 5 The secret war in the United States 51 6 The secret war in Italy 63 7 The secret war in France 84 8 The secret war in Spain 103 9 The secret war in Portugal 114 10 The secret war in Belgium 125 11 The secret war in the Netherlands 148 12 The secret war in Luxemburg 165 ix 13 The secret war in Denmark 168 14 The secret war in Norway 176 15 The secret war in Germany 189 16 The secret war in Greece 212 17 The secret war in Turkey 224 Conclusion 245 Chronology 250 Notes 259 Select bibliography 301 Index 303 x FOREWORD At the height of the Cold War there was effectively a front line in Europe. Winston Churchill once called it the Iron Curtain and said it ran from Szczecin on the Baltic Sea to Trieste on the Adriatic Sea. Both sides deployed military power along this line in the expectation of a major combat. The Western European powers created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) precisely to fight that expected war but the strength they could marshal remained limited. The Soviet Union, and after the mid-1950s the Soviet Bloc, consistently had greater numbers of troops, tanks, planes, guns, and other equipment. This is not the place to pull apart analyses of the military balance, to dissect issues of quantitative versus qualitative, or rigid versus flexible tactics. -

180203 the Argentine Military and the Antisubversivo Genocide

Journal: GSI; Volume 11; Issue: 2 DOI: 10.3138/gsi.11.2.03 The Argentine Military and the “Antisubversivo” Genocide DerGhougassian and Brumat The Argentine Military and the “Antisubversivo ” Genocide: The School of Americas’ Contribution to the French Counterinsurgency Model Khatchik DerGhougassian UNLa, Argentina Leiza Brumat EUI, Italy Abstract: The article analyzes role of the United States during the 1976–1983 military dictatorship and their genocidal counterinsurgency war in Argentina. We argue that Washington’s policy evolved from the initial loose support of the Ford administration to what we call “the Carter exception” in 1977—79 when the violation of Human Rights were denounced and concrete measures taken to put pressure on the military to end their repressive campaign. Human Rights, however, lost their importance on Washington’s foreign policy agenda with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the end of the Détente. The Argentine military briefly recuperated US support with Ronald Reagan in 1981 to soon lose it with the Malvinas War. Argentina’s defeat turned the page of the US support to military dictatorships in Latin America and marked the debut of “democracy promotion.” Keywords: Proceso, dirty war, human rights, Argentine military, French School, the School of the Americas, Carter Page 1 of 48 Journal: GSI; Volume 11; Issue: 2 DOI: 10.3138/gsi.11.2.03 Introduction: Framing the US. Role during the Proceso When an Argentine military junta seized the power on March 24, 1976 and implemented its “ plan antisubversivo ,” a supposedly counterinsurgency plan to end the political violence in the country, Henry Kissinger, the then United States’ Secretary of State of the Gerald Ford Administration, warned his Argentine colleague that the critiques for the violation of human rights would increment and it was convenient to end the “operations” before January of 1977 when Jimmy Carter, the Democratic candidate and winner of the presidential elections, would assume the power in the White House. -

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra-kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter-stock.com @IERES2019 Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

Bulletin 10-Final Cover

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN Issue 10 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. March 1998 Leadership Transition in a Fractured Bloc Featuring: CPSU Plenums; Post-Stalin Succession Struggle and the Crisis in East Germany; Stalin and the Soviet- Yugoslav Split; Deng Xiaoping and Sino-Soviet Relations; The End of the Cold War: A Preview COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 10 The Cold War International History Project EDITOR: DAVID WOLFF CO-EDITOR: CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN ADVISING EDITOR: JAMES G. HERSHBERG ASSISTANT EDITOR: CHRISTA SHEEHAN MATTHEW RESEARCH ASSISTANT: ANDREW GRAUER Special thanks to: Benjamin Aldrich-Moodie, Tom Blanton, Monika Borbely, David Bortnik, Malcolm Byrne, Nedialka Douptcheva, Johanna Felcser, Drew Gilbert, Christiaan Hetzner, Kevin Krogman, John Martinez, Daniel Rozas, Natasha Shur, Aleksandra Szczepanowska, Robert Wampler, Vladislav Zubok. The Cold War International History Project was established at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., in 1991 with the help of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and receives major support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Smith Richardson Foundation. The Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to disseminate new information and perspectives on Cold War history emerging from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side”—the former Communist bloc—through publications, fellowships, and scholarly meetings and conferences. Within the Wilson Center, CWIHP is under the Division of International Studies, headed by Dr. Robert S. Litwak. The Director of the Cold War International History Project is Dr. David Wolff, and the incoming Acting Director is Christian F. -

Linkiesta.It - Delle Chiaie, L’Uomo Dei Misteri: “Un Sovversivo Megalomane E Teatrale”

Linkiesta.it - Delle Chiaie, l’uomo dei misteri: “Un sovversivo megalomane e teatrale” Il docente Elia Rosati ricorda i tanti segreti che Stefano Delle Chiaie, esponente della destra radicale italiana, si è portato con sé nella tomba. Misteri legati alle stragi nere di Piazza Fontana e Bologna. Latitante fino al 1987, è morto a 83 anni «Qual è la sua professione?». Risposta: «Sono un rivoluzionario al servizio dell’idea». Quella fascista, naturalmente. Con la morte di Stefano Delle Chiaie, scompare l’ultimo “grande vecchio” del neofascismo italiano, accusato di concorso in strage nell’attentato di Bologna del 1980, ma assolto poi per insufficienza di prove. «La teatralità e l’autocompiacenza erano il suo tratto distintivo», dice Elia Rosati, docente a contratto dell’Università degli Studi di Milano, esperto di destre e fascismo. Due tratti che emergono nell’intervista concessa a Enzo Biagi in una foresta colombiana durante la latitanza, nel 1983, prima di essere catturato nel 1987 a Caracas. Il periodo all’estero fu una delle tante fasi nella vita della primula nera del terrorismo, vero e proprio spauracchio evocato in tutte le stragi e i disordini di matrice fascista che insanguinarono l’Italia tra gli anni Sessanta e Settanta. «Delle Chiaie fu il simbolo di Avanguardia Nazionale e, insieme a Rauti, Graziani e Freda, uno dei dirigenti più importanti del mondo della destra extraparlamentare», spiega Rosati. Il golpe Borghese? Un colpo di Stato ipotetico, ma se ci fosse stato realmente io ne avrei fatto parte Noto sin dalla metà degli anni Sessanta nel mondo della destra eversiva romana, fu uno dei leader delle bande di picchiatori fascisti responsabili della morte dello studente socialista Paolo Rossi nel 1966, precipitato da una scalinata a seguito dei durissimi scontri davanti alla facoltà di Lettere, e nel 1968 tentò di inflitrarsi con le sue bande durante gli scontri di Valle Giulia. -

Virtual Currencies: International Actions and Regulations Last

Virtual Currencies: International Actions and Regulations Last Updated: January 8, 2021 No Legal Advice or Attorney-Client Relationship: This chart is provided by Perkins Coie LLP’s Decentralized Virtual Currency industry practice group for informational purposes only and is not legal advice. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. Recipient should not act upon this information without seeking advice from a lawyer licensed in his/her own state or country. For questions or comments regarding this chart, please contact [email protected]. Developments Over Time Country Current Summary Date Occurrence Sources 2/20/2020 The Financial Services Regulatory Authority has updated and Guidance expanded its guidance through amendments to its cryptoasset regulatory framework. The amendments change the terminology used in the framework from “crypto asset” to “virtual asset,” a change that aligns with those descriptions used by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) (see Issuers and intermediaries of virtual Financial Action Task Force (below)). The FATF currencies and “security” tokens may be recommendations are an international standard for regulation Abu Dhabi subject to regulation—depending upon of crypto assets including KYC requirements, anti-money the nature of the product and service. laundering and fraud prevention rules, and sanctions and screening controls. The amendments also overhaul regulations to move the applicable rules from a singular category to those respective to the underlying activities. This means that such assets can be regulated according to their idiosyncratic natures and not as a monolithic class. 29032535.40 10/09/2017 The Financial Services Regulatory Authority (FSRA) of Abu Supplementary Dhabi issued guidance on the regulation of initial coin/token Guidance – Regulation offerings (ICO) and digital currency as supplemental of Initial Coin/Token guidance to the existing 2015 Financial Services and Markets Offerings and Virtual Regulations (FSMR).