Incendiarism, Rural Order and England's Last Scene of Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2017 Antonia Pugh-Thomas

Drumming up something new WINTER 2017 ANTONIA PUGH-THOMAS Haute Couture Shrieval Outfits for Lady High Sheriffs 0207731 7582 659 Fulham Road London, SW6 5PY www.antoniapugh-thomas.co.uk Volume 36 Issue 2 Winter 2017 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL 14 20 Officers and Council November 2016 to November 2017 OFFICERS Chairman The Hon HJH Tollemache 30 38 Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary J H A Williams Esq Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory Esq DL Thorpland Hall, Fakenham Norfolk NR21 0HD Tel 01328 862392 Email [email protected] COUNCIL Col M G C Amlôt OBE DL Canon S E A Bowie DL Mrs E J Hunter D C F Jones Esq DL JAT Lee Esq OBE Mrs VA Lloyd DL Lt Col AS Tuggey CBE DL W A A Wells Esq TD (Hon Editor of The High Sheriff ) Mrs J D J Westoll MBE DL Mrs B Wilding CBE QPM DL The High Sheriff is published twice a year by Hall-McCartney Ltd for the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales Hon Editor Andrew Wells Email [email protected] ISSN 1477-8548 4 From the Editor 13 Recent Events – 20 General Election © 2017 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales From the new Chairman The City and the Law The Association is not as a body responsible for the opinions expressed 22 News – from in The High Sheriff unless it is stated Chairman’s and about members that an article or a letter officially 6 14 Recent represents the Council’s views. -

Summer 2017 Antonia Pugh-Thomas

Young people creating safer communities SUMMER 2017 ANTONIA PUGH-THOMAS Haute Couture Shrieval Outfits for Lady High Sheriffs 0207731 7582 659 Fulham Road London, SW6 5PY www.antoniapugh-thomas.co.uk Keystone is an independent consultancy which prioritises the needs and aspirations of its clients with their long-term interests at the centreoftheir discussions on their often-complex issues around: Family assets l Governance l Negotiation l Optimal financing structures l Accurate data capturefor informed decision-making l Mentoring and informal mediation These areall encapsulated in adeveloped propriety approach which has proved transformational as along-term strategic planning tool and ensures that all discussions around the family enterprise with its trustees and advisers arebased on accurate data and sustainable finances Advising families for the 21st Century We work with the family offices, estate offices, family businesses, trustees, 020 7043 4601 |[email protected] lawyers, accountants, wealth managers, investment managers, property or land agents and other specialist advisors www.keystoneadvisers.uk Volume 36 Issue 1 Summer 2017 the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL Officers and Council November 2016 to November 2017 11 14 OFFICERS Chairman J J Burton Esq DL Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary 24 34 J H A Williams Esq Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Fax 07092 846777 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory -

A History of Landford in Wiltshire

A History of Landford in Wiltshire Appendix 3 – Other families connected with the Eyres of Newhouse, Brickworth, Landford and Bramshaw The genealogical details of the various families connected with the Eyre family have been compiled from various sources using information taken from the Internet. Not all sources are 100% reliable and there are conflicting dates for births, marriages and deaths, particularly for the earlier generations. Subsequently the details given in this account may also perpetuate some of those errors. The information contained in this document is therefore for general information purposes only and whilst I have tried to ensure that the information given is correct, I cannot guaranty the accuracy or reliability of the sources used or the information contained in this document. Anyone using this website for family reasons needs to be aware of this. CONTENTS Page 2 Introduction Page 2 The Rogers of Bryanston, Dorset Page 4 The Bayntuns of Bromham, Wiltshire Page 13 The Alderseys of Aldersey and Spurstow, Cheshire Page 16 The Lucys of Charlcote, Warwickshire Page 20 The Tropenell family of Great Chalfield, Wiltshire Page 22 The Nortons of Rotherfield, East Tisted, Hants Page 28 The Ryves of Ranston, Dorset Page 32 The Wyndhams of Kentsford, Somerset and Felbrigg, Norfolk Page 41 The Briscoe and Hulse family connections Page 44 The Richards of Penryn, Cornwall John Martin (Jan 2019) Page 1 of 45 A History of Landford in Wiltshire Appendix 3 – Other families connected with the Eyres of Newhouse, Brickworth, Landford and Bramshaw Introduction Whilst researching the historical background regarding the development of Landford and the ownership of the larger estates, it soon became apparent that members of the Eyre family played an important role in the social and political life of this part of Wiltshire. -

The Descendants of John Pease 1

The Descendants of John Pease 1 John Pease John married someone. He had three children: Edward, Richard and John. Edward Pease, son of John Pease, was born in 1515. Basic notes: He lived at Great Stambridge, Essex. From the records of Great Stambridge. 1494/5 Essex Record office, Biography Pease. The Pease Family, Essex, York, Durham, 10 Henry VII - 35 Victoria. 1872. Joseph Forbe and Charles Pease. John Pease. Defendant in a plea touching lands in the County of Essex 10 Henry VII, 1494/5. Issue:- Edward Pease of Fishlake, Yorkshire. Richard Pease of Mash, Stanbridge Essex. John Pease married Juliana, seized of divers lands etc. Essex. Temp Henry VIII & Elizabeth. He lived at Fishlake, Yorkshire. Edward married someone. He had six children: William, Thomas, Richard, Robert, George and Arthur. William Pease was born in 1530 in Fishlake, Yorkshire and died on 10 Mar 1597 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. William married Margaret in 1561. Margaret was buried on 25 Oct 1565 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. They had two children: Sibilla and William. Sibilla Pease was born on 4 Sep 1562 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. Basic notes: She was baptised on 12 Oct 1562. Sibilla married Edward Eccles. William Pease was buried on 25 Apr 1586. Basic notes: He was baptised on 29 May 1565. William next married Alicia Clyff on 25 Nov 1565 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. Alicia was buried on 19 May 1601. They had one daughter: Maria. Maria Pease Thomas Pease Richard Pease Richard married Elizabeth Pearson. Robert Pease George Pease George married Susanna ?. They had six children: Robert, Nicholas, Elizabeth, Alicia, Francis and Thomas. -

Newton St Loe, Bath – Memorial Inscriptions

Newton St Loe, Bath – Memorial Inscriptions Names Inscriptions Notes 1 Mary Gawen (1740- 1797) of A____________ Joseph Gawen (1704- of _______ 1799) She died ________ Aged __ Likewise the Remains of the above JOSEPH GAWEN who departed this Life Jan. 4th 1799 Aged 74 Large rectangular headstone. The top half is delaminated. 1A Giles Baine (1704-1775) G B 1775 M B 1778 Mary Baine (-1778) J B 1787 John Baine (-1787) Small headstone. 2 Chest tomb. No inscription found. 1 Newton St Loe, Bath – Memorial Inscriptions Names Inscriptions Notes 3 Small headstone. No inscription found. 4 James Smith (1748- The Bodies of 1749) James and William Sones of JAMES and MARY SMITH of Ye Pish William Smith (1749- James Died 26. March 1749. Aged 3M. 1757) Wm died __ Janur 1757. Aged 7Yrs6M. 5 6 2 Newton St Loe, Bath – Memorial Inscriptions Names Inscriptions Notes 7 Martha Deverill (-1768) In Memory of Martha, Wife Daniel Deverill (-1779) of Daniel Deverill who died 6 March 1768. Aged 66. John Deverill Also ye said Daniel Deverill Died 20 Octr 1779 Aged 80. And of John Deverill their Son who died 5 Headstone. 7A Small headstone. No inscription found. 8 Mary Thatcher (1727- Here Lie the Bodys 1728) of Two Daughters and One Son of JAMES and SARAH THATCHER of this Parish Sarah Thatcher (1737- MARY died May 10. 1728. Aged 1Yr2Mo 1738) SARAH March 24, 1738. Aged 17WKS JAMES August 13. 1743. Aged 6Y3M James Thatcher (1737- Also here lieth the Body of ye above 1743) mentioned JAMES THATCHER who Departed this Life the 8th of January Small headstone. -

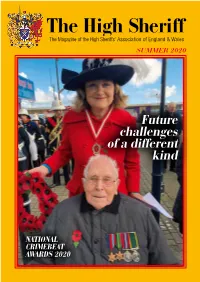

Future Challenges of a Different Kind

SUMMER 2020 Future challenges of a different kind NATIONAL CRIMEBEAT AWARDS 2020 www Lady Shrieval .antoniapugh-thom High Ant Haute dr ess Sheriffs onia for Coutur Pugh- as.co.uk eW omensw Thomas 020 ear 7731 7582 Photo courtesy of Harald Altmaier Volume 39 Issue 1 Summer 2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales President J R Avery Esq DL 12 15 Officers and Council 2020 OFFICERS Chairman The Hon H J H Tollemache Email [email protected] Honorary Secretary 34 38 J H A Williams Esq MBE Gatefield, Green Tye, Much Hadham Hertfordshire SG10 6JJ Tel 01279 842225 Email [email protected] Honorary Treasurer N R Savory Esq DL Thorpland Hall, Fakenham Norfolk NR21 0HD Tel 01328 862392 Email [email protected] COUNCIL Canon S E A Bowie DL T H Birch Reynardson Esq D C F Jones Esq DL J A T Lee Esq OBE DL Mrs V A Lloyd DL Mrs A J Parker JP DL Dr R Shah MBE JP DL Lt Col A S Tuggey CBE DL W A A Wells Esq TD (Hon Editor of The High Sheriff ) S J Young Esq MC JP DL The High Sheriff is published twice a year by Hall-McCartney Ltd for the High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales Hon Editor Andrew Wells Email [email protected] ISSN 1477-8548 ©2020 The High Sheriffs’ Association of England and Wales 4 From the Editor 12 General Election 44 Association regalia The Association is not as a body responsible for the opinions expressed and publications in The High Sheriff unless it is stated The ‘Red Mass’ that an article or a letter officially Diary 15 represents the Council’s views. -

General Somersetshire Notes

OF THE BLOOD ROYAL OF ENGLAND and GENERAL SOMERSETSHIRE NOTES OF THE BLOOD ROYAL OF ENGLAND [Page 178 of the book contains a chart that traces the lineage of Rector Charles Alford and his son Bishop Charles Richard Alford to royalty. Charles Richard Alford is the father of Josiah Alford, the author of Alford Family Notes. The chart is reprinted below, slightly modified. This family is discussed fully in AAFA ACTION, Fall 1993, “Part 19, Josiah Alford’s Alford Family Notes,” pp. 12–20. Descendancy charts for this family tracing the Alford lineage back to Henry Alford of Weston Zoyland (will dated 1575), appear on pp. 116 and 132 of the book, but they were not reproduced for this publication.] "OF THE BLOOD ROYAL OF ENGLAND was Sir John Stourton, of Stourton, co. Wilts, and of Stavordale, co. Somerset, High Sheriff of Somerset," 1428 and 1431. "In direct descent from the King, and entitled to quarter the Plantagenet Arms" (Harl. MSS. 1110, 1155, 1074, Brit. Mus. Lib.) Married i, Catherine, d. of Lord Beaumont; ii, Jane, d. of Lord Bassett. [Son of John and Jane] John Stourton, of Preston, co. Somerset, m. iii, Catherine Payne. [Their daughter] Joan Alice Stourton m. John Sydenham, M.P., of Brympton, and Combe Sydenham, High Sheriff co. Somerset, 1465. [Their son] Walter Sydenham, of Brympton, co. Somerset, d. 1469. He m. Margaret, d. of Sir Wm. Harcourt. [Their son] John Sydenham, of Brympton, M.P., High Sheriff of co. Somerset in 1506. He m. Elizabeth,d. of Sir Humphrey Audley. [Their son] Thomas Sydenham (younger son) of Whestow, co. -

March 2015 1

RoundRound AboutAbout the villages of Langford Budville and Runnington March 2015 1 CONTENTS 1 Welcome 2 What's On 4 All About Round About 5 Green Fingers: Pruning 6 Village Hall 10 News from the Villages 12 David Percy 13 Community Contacts 14 Mad March Hares 16 A Walk Back in Time Part 2 18 News from the Churches 22 Dairy Delights: Bread 23 Langford Ladies 24 Langford Budville Arch 25 The Night Sky 26 Young Buddies 27 Our School 35 Magazine Info/Ad Rates 36 Bus Timetable 2 Welcome... ... to the March edition of Round About. We’re Out and About with Hares this month, as you’ll guess from the cover. We’ve illustrated our article with images taken, with permission, from the work of local artist, the late Richard Pocock. March sees the days lengthening, and spring seems well on the way with snowdrops brightening our gardens, and tempting us out of doors— where we are faced with the need to shape up in the garden. Green Fingers will give you some hints! In Village News we welcome several recent arrivals in the villages, and congratulate our Bell Ringers on their recent ringing success. We also bid farewell to a former resident. Once again Marilyn goes walking around Langford Budville as it was in the 1940s, in the second half of a Walk Back in Time. And we wonder if anyone recognises where our own Arch was erected—and when? Those of us who enjoy the lovely Soup Lunches at St Peter’s church will welcome our Dairy Delights recipe this month—we feature Trevor Pritchard’s delicious bread recipe. -

Report of Tfje Curator of Caunton Castle Museum

Report of tfje Curator of Caunton Castle Museum for tfte pear entitng December 3ist, 1909. A LTHOUGrH the objects acquired for the Museum during 1909 are, numerically, rather fewer than for the last two or three years, some of the acquisitions, especially those of archaeological and local interest, are of great importance. Foremost among these is the gold tore, or necklet, of the Bronze Age found at Yeovil, which is fully dealt with by tbe Curator in a paper in the second part of this volume (Proc. Som. Arch. Soc, lv, 1909). A facsimile of the tore, in silver-gilt, has been made for exhibition, but the original can be seen on application by those specially interested in the dis- covery. From excavations conducted by the Curator, additions have been made to the Museum from Charterhouse-on-Mendip and Maumbury Rings, Dorchester ; while another series of antler picks and other objects found in the excavations at Avebury are temporarily exhibited, and the 1907 relics from the Glaston- bury Lake Village are still on view in the Society's Museum. Excavations have also accounted for archaeological acquisitions " from Downend, Preston Plucknett and Portland. " Finds from quarrying operations on Ham Hill have perhaps not been so numerous this year, but some of the objects from that place, added to the Museum by Mr. Hensleigh Walter during 1909, are of considerable interest. Of other acquisitions of local interest the Museum has been enriched by a staff of office of the ancient borough of Newport, North Curry, the old coach of the High Sheriff of Somerset, and the Tudor archway of oak removed from the site of the 86 Sixty-first Annual Meeting, new Post Office at Taunton. -

Lord North Papers a Handlist

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES TEL: 01782 733237 EMAIL: [email protected] LIBRARY Ref code : GB 172 N Lord North Papers A handlist Librarian: Paul Reynolds Library Telephone: (01782) 733232 Fax: (01782) 734502 Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, United Kingdom Tel: +44(0)1782 732000 http://www.keele.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF KEELE (Lists of Archives) Accession No. or Code: N Name and Address of Owner : University of Keele, Keele, Staffordshire. ~ccumulatio~or .Lord North's papers, part of the Raymond Richards Collection: Collection. Class : Private Reference . Date : Item: Number : LORD NORTH & GUZI,FORD, LATER 1ST EARL OF GUILFORD, AS EXECUTOR OF WILLIAM MOORE, ESQ-I OF POLESDEN, SURREY (d.1746) Moore family papers I N 1. 1690-1738 Deeds Property: ano or of Cornwalls, mansion house in Thirwuy, farm near Iver and' pepper mill in Iver, all in Backinghamshire; manor of Pollesden in Great Ejookham, Surrey, half parsonage of Great Eookhm, and meadcw called Hale mead in Leather- head, Surrey; "the little house of flea'lf; farm of Stumblehole in the parishes of Ifield and Rusper, Sussex. Parties: Henry and Richard Berringer of Iver, Bucks., John Hayes of London and Thomas Hampton of Cowley , Middx. ; Thomas Berenger of Iver, Bucks., and Arthur Moore of London; Richard Cook; Thomas Harris of Dorking, Surrey; Thomas Moore and Thomas Reeve; Thomas Oneley of Fradley and William Moore of Polsden. Business and estate correspondence, receipts, etc. Property : Walton Grounds ; manor of Ockley . [surrey]; estate in Cobham; estate in Gloucestershire; Frodley Hall. N 3. 1745 & [18th cent1 Correspondence of William Moore, esq. , M.P . -

College Notes 1920S

Eagle .')0 Tlte Tlte Holl. ]Oll� died al ollege N oles SI FHEDERICI{ GIWNING, C'. l.E., J><ll lla cto e aged 52. He was educated at Eastbourne 1'I1r James Donald (Matric. I895)", een C.I.E., I.C.S., has b Col011 Olege bandr 3, at H) 22,St John's, where he matriculated in 1892. appointed a member of thr. Executive Council to the Governor The same year he entered the Indian Civil Service ; he became of Bengal . 7I1 agistrate and Collector in 1906, and since 1917 had been P. J. (B.A. It)IZ) has accompanied the British iVlr. Grigg Commissioner of the Orissa Division. He compiled for the Financial Mission to the United States as Private Sec etary lo r Government of Bengal a Gazetteer of the ]al paig i district, the Chancellor o[ the Exchequer. which was published in 1911. ur Sir Eclwarc1 :'I1arshall-Hall. K.c. (B.A. I883) has been The Venerable PERCY HAHRIS BOWERS (B.A. 1879) , elected Master of the Loriners' Company H . Archdeacon of Loughborough, died at his Rectory, Sir llmphrey Rolleston (B.A. 188('), has been appointed Bosworth, Nuneaton , on November IS, It)22, after Marketa long representative of the Royal College of Phvsicians on the illness, aged 67· He was ordained in 1886, was curate General lVledical Council. successively of Fladbury and Leyland, and was presented to The nominations to the Council Lhe Royal SocieLy of the rectory of Market Bosworth with Shenton in 1886. He include the ol lo\\'in members of the College :-Sir Arthur [ g became Rural Dean of Sparkenhoe in 1909, an Honorary 'Schuster ( Fore ign Secretary) , Professors V. -

A History of Dunster and of the Families of Mohun & Luttrell

A HISTORY OF D UNST ER A HISTORY OF D U N ST E R AND OF THE FAMILIES OF MOHUN ^ LUTTRELL BY SIR H.C.MAXWELL LYTE,K.C.B. Deputy Keeper of the Records. PART II I L L us T RA TED LONDON THE ST. CATHERINE PRESS LTD 8 YORK BUILDINGS, ADELPHI 1909 t^ CHAPTER X. The topography of Dunster, The station of the Great Western Railway bearing the name of ' Dunster ' is actually in the parish of Carhampton. A little to the south of it stands Marsh Bridge, formerly of some importance as situate on the road between the Haven, or sea-port, of Dunster and the town. It was reckoned to be in Dunster, and in the middle ages the commonalty of that borough was responsible for its maintenance. ^ Higher Marsh, now a farmhouse close by, seems to occupy the site of Marsh Place, the cradle of the Stewkleys, who eventually became rich and migrated to Hinton Ampner in Hampshire. Further south are several scattered houses, dignified collectively by the name of Marsh Street. There were formerly two public approaches to the town of Dunster from the north. One of these, known in the fourteenth century as Brook Lane, diverged from the highroad between Carhampton and Minehead at the western end of Loxhole Bridge, formerly Brooklanefoot Bridge, which spans the river that there divides the parishes of Carhampton and Dunster. ^ The other, skirting round the eastern side of Conigar, was a southern continuation of Marsh Street, and was anciently known as St. Thomas's Street, ' D.C.M.