Cleavage: This Term Refers to the Series of Mitotic Divisions by Which the Large Zygote Is Fractionated Into Numerous “Normal Size” Cells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Embryology and Development

BIOL 6505 − INTRODUCTION TO FETAL MEDICINE 3. EMBRYOLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT Arlet G. Kurkchubasche, M.D. INTRODUCTION Embryology – the field of study that pertains to the developing organism/human Basic embryology –usually taught in the chronologic sequence of events. These events are the basis for understanding the congenital anomalies that we encounter in the fetus, and help explain the relationships to other organ system concerns. Below is a synopsis of some of the critical steps in embryogenesis from the anatomic rather than molecular basis. These concepts will be more intuitive and evident in conjunction with diagrams and animated sequences. This text is a synopsis of material provided in Langman’s Medical Embryology, 9th ed. First week – ovulation to fertilization to implantation Fertilization restores 1) the diploid number of chromosomes, 2) determines the chromosomal sex and 3) initiates cleavage. Cleavage of the fertilized ovum results in mitotic divisions generating blastomeres that form a 16-cell morula. The dense morula develops a central cavity and now forms the blastocyst, which restructures into 2 components. The inner cell mass forms the embryoblast and outer cell mass the trophoblast. Consequences for fetal management: Variances in cleavage, i.e. splitting of the zygote at various stages/locations - leads to monozygotic twinning with various relationships of the fetal membranes. Cleavage at later weeks will lead to conjoined twinning. Second week: the week of twos – marked by bilaminar germ disc formation. Commences with blastocyst partially embedded in endometrial stroma Trophoblast forms – 1) cytotrophoblast – mitotic cells that coalesce to form 2) syncytiotrophoblast – erodes into maternal tissues, forms lacunae which are critical to development of the uteroplacental circulation. -

Cleavage of Cytoskeletal Proteins by Caspases During Ovarian Cell Death: Evidence That Cell-Free Systems Do Not Always Mimic Apoptotic Events in Intact Cells

Cell Death and Differentiation (1997) 4, 707 ± 712 1997 Stockton Press All rights reserved 13509047/97 $12.00 Cleavage of cytoskeletal proteins by caspases during ovarian cell death: evidence that cell-free systems do not always mimic apoptotic events in intact cells Daniel V. Maravei1, Alexander M. Trbovich1, Gloria I. Perez1, versus the cell-free extract assays (actin cleaved) raises Kim I. Tilly1, David Banach2, Robert V. Talanian2, concern over previous conclusions drawn related to the Winnie W. Wong2 and Jonathan L. Tilly1,3 role of actin cleavage in apoptosis. 1 The Vincent Center for Reproductive Biology, Department of Obstetrics and Keywords: apoptosis; caspase; ICE; CPP32; actin; fodrin; Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, proteolysis; granulosa cell; follicle; atresia Boston, Massachusetts 02114 USA 2 Department of Biochemistry, BASF Bioresearch Corporation, Worcester, Massachusetts 01605 USA Abbreviations: caspase, cysteine aspartic acid-speci®c 3 corresponding author: Jonathan L. Tilly, Ph.D., Massachusetts General protease (CASP, designation of the gene); ICE, interleukin- Hospital, VBK137E-GYN, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, Massachusetts 1b-converting enzyme; zVAD-FMK, benzyloxycarbonyl-Val- 02114-2696 USA. tel: +617 724 2182; fax: +617 726 7548; Ala-Asp-¯uoromethylketone; zDEVD-FMK, benzyloxycarbo- e-mail: [email protected] nyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-¯uoromethylketone; kDa, kilodaltons; Received 28.1.97; revised 24.4.97; accepted 14.7.97 ICH-1, ICE/CED-3 homolog-1; CPP32, cysteine protease Edited by J.C. Reed p32; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose)-polymerase; MW, molecular weight; STSP, staurosporine; C8-CER, C8-ceramide; DTT, dithiothrietol; cCG, equine chorionic gonadotropin (PMSG or Abstract pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin); ddATP, dideoxy-ATP; kb, kilobases; HEPES, N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N'-(2- Several lines of evidence support a role for protease ethanesulfonic acid); SDS ± PAGE, sodium dodecylsulfate- activation during apoptosis. -

Determination of Cell Development, Differentiation and Growth

Pediat. Res. I: 395-408 (1967) Determination of Cell Development, Differentiation and Growth A Review D.M.BROWN[ISO] Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA Introduction plasmic synthesis, water uptake, or, in the case of intact tissue, intercellular deposition. It may include prolifera It has become increasingly apparent that the basis for tion or the multiplication of identical cells and may be biologic variation in relation to disease states is in accompanied by differentiation which implies anatomical large part predetermined from early embryonic stages. as well as functional changes. The number of cellular Consideration of variations of growth and development units in a tissue may be related to the deoxyribonucleic must take into account the genetic constitution and acid (DNA) content or nucleocytoplasmic units [24, early embryonic events of tissue and organ develop 59, 143]. Differentiation may refer to physical and ment. chemical organization of subcellular components or The incidence of congenital malformation has been to changes in the structure and organization of cells estimated to be 2 to 3 percent of all live born infants and leading to specialized organs. may double by one year [133]. Minor abnormalities are even more common [79]. Furthermore, the large variety of well-defined 'inborn errors of metabolism', Control of Embryonic Chemical Development as well as the less apparent molecular and chromosomal abnormalities, should no doubt be considered as mal Protein syntheses during oogenesis and embryogenesis formations despite the possible lack of gross somatic are guided by nuclear and nucleolar ribonucleic acid aberrations. Low birth weight is a frequent accom (RNA) which are in turn controlled by primer DNA. -

The Zebrafish Presomitic Mesoderm Elongates Through Compression-Extension

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.11.434927; this version posted March 11, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. The zebrafish presomitic mesoderm elongates through compression-extension Lewis Thomson1, Leila Muresan2 and Benjamin Steventon1* 1) Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, CB2 3EH 2) Cambridge Advanced Imaging Centre, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK *[email protected] Abstract In vertebrate embryos the presomitic mesoderm become progressively segmented into somites at the anterior end while extending along the anterior- posterior axis. A commonly adopted model to explain how this tissue elongates is that of posterior growth, driven in part by the addition of new cells from uncommitted progenitor populations in the tailbud. However, in zebrafish, much of somitogenesis is associated with an absence of overall volume increase and posterior progenitors do not contribute new cells until the final stages of somitogenesis. Here, we perform a comprehensive 3D morphometric analysis of the paraxial mesoderm and reveal that extension is linked to a volumetric decrease, compression in both dorsal-ventral and medio-lateral axes, and an increase in cell density. We also find that individual cells decrease in their cell volume over successive somite stages. Live cell tracking confirms that much of this tissue deformation occurs within the presomitic mesoderm progenitor zone and is associated with non-directional rearrangement. Furthermore, unlike the trunk somites that are laid down during gastrulation, tail somites develop from a tissue that can continue to elongate in the absence of functional PCP signalling. -

The Migration of Neural Crest Cells and the Growth of Motor Axons Through the Rostral Half of the Chick Somite

/. Embryol. exp. Morph. 90, 437-455 (1985) 437 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1985 The migration of neural crest cells and the growth of motor axons through the rostral half of the chick somite M. RICKMANN, J. W. FAWCETT The Salk Institute and The Clayton Foundation for Research, California division, P.O. Box 85800, San Diego, CA 92138, U.S.A. AND R. J. KEYNES Department of Anatomy, University of Cambridge, Downing St, Cambridge, CB2 3DY, U.K. SUMMARY We have studied the pathway of migration of neural crest cells through the somites of the developing chick embryo, using the monoclonal antibodies NC-1 and HNK-1 to stain them. Crest cells, as they migrate ventrally from the dorsal aspect of the neural tube, pass through the lateral part of the sclerotome, but only through that part of the sclerotome which lies in the rostral half of each somite. This migration pathway is almost identical to the path which pre- sumptive motor axons take when they grow out from the neural tube shortly after the onset of neural crest migration. In order to see whether the ventral root axons are guided along this pathway by neural crest cells, we surgically excised the neural crest from a series of embryos, and examined the pattern of axon outgrowth approximately 24 h later. In somites which contained no neural crest cells, ventral root axons were still found only in the rostral half of the somite, although axonal growth was slightly delayed. These axons were surrounded by sheath cells, which had presumably migrated out of the neural tube, to a point about 50 jan proximal to the growth cones. -

Sperm Penetration and Early Patterning in the Mouse 5805

Development 129, 5803-5813 5803 © 2002 The Company of Biologists Ltd doi:10.1242/dev.00170 Early patterning of the mouse embryo – contributions of sperm and egg Karolina Piotrowska* and Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz† Wellcome Trust/Cancer Research UK Institute, and Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge CB2 1QR, UK *On leave from the Department of Experimental Embryology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Jastrzebiec, Poland †Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 12 September 2002 SUMMARY The first cleavage of the fertilised mouse egg divides the 2-cell blastomere to divide in parthenogenetic embryo does zygote into two cells that have a tendency to follow not necessarily contribute more cells to the blastocyst. distinguishable fates. One divides first and contributes its However, even when descendants of the first dividing progeny predominantly to the embryonic part of the blastomere do predominate, they show no strong blastocyst, while the other, later dividing cell, contributes predisposition to occupy the embryonic part. Thus mainly to the abembryonic part. We have previously blastomere fate does not appear to be decided by observed that both the plane of this first cleavage and the differential cell division alone. Finally, when the cortical subsequent order of blastomere division tend to correlate cytoplasm at the site of sperm entry is removed, the first with the position of the fertilisation cone that forms after cleavage plane no longer tends to divide the embryo sperm entry. But does sperm entry contribute to assigning into embryonic and abembryonic parts. Together these the distinguishable fates to the first two blastomeres or is results indicate that in normal development fertilisation their fate an intrinsic property of the egg itself? To answer contributes to setting up embryonic patterning, alongside this question we examined the distribution of the progeny the role of the egg. -

Human Blastocyst Morphological Quality Is Significantly Improved In

Human blastocyst morphological quality is significantly improved in embryos classified as fast on day 3 (R10 cells), bringing into question current embryological dogma Martha Luna, M.D.,a,b Alan B. Copperman, M.D.,a,b Marlena Duke, M.Sc.,a,b Diego Ezcurra, D.V.M.,c Benjamin Sandler, M.D.,a,b and Jason Barritt, Ph.D.a,b a Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Department of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, and b Reproductive Medicine Associates of New York, New York, New York; and c EMD Serono, Rockland, Massachusetts Objective: To evaluate developmental potential of fast cleaving day 3 embryos. Design: Retrospective analysis. Setting: Academic reproductive center. Patient(s): Three thousand five hundred twenty-nine embryos. Intervention(s): Day 3 embryos were classified according to cell number: slow cleaving: %6 cells, intermediate cleaving: 7–9 cells, and fast cleaving: R10 cells, and further evaluated on day 5. The preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) results of 43 fast cleaving embryos were correlated to blastocyst formation. Clinical outcomes of transfers involving only fast cleaving embryos (n ¼ 4) were evaluated. Main Outcome Measure(s): Blastocyst morphology correlated to day 3 blastomere number. Relationship between euploidy and blastocyst formation of fast cleaving embryos. Implantation, pregnancy (PR), and birth rates resulting from fast embryo transfers. Result(s): Blastocyst formation rate was significantly greater in the intermediate cleaving (72.7%) and fast cleav- ing (54.2%) groups when compared to the slow cleaving group (38%). Highest quality blastocysts were formed significantly more often in the fast cleaving group. Twenty fast cleaving embryos that underwent PGD, formed blastocysts, of which 45% (9/20) were diagnosed as euploid. -

The Genetic Basis of Mammalian Neurulation

REVIEWS THE GENETIC BASIS OF MAMMALIAN NEURULATION Andrew J. Copp*, Nicholas D. E. Greene* and Jennifer N. Murdoch‡ More than 80 mutant mouse genes disrupt neurulation and allow an in-depth analysis of the underlying developmental mechanisms. Although many of the genetic mutants have been studied in only rudimentary detail, several molecular pathways can already be identified as crucial for normal neurulation. These include the planar cell-polarity pathway, which is required for the initiation of neural tube closure, and the sonic hedgehog signalling pathway that regulates neural plate bending. Mutant mice also offer an opportunity to unravel the mechanisms by which folic acid prevents neural tube defects, and to develop new therapies for folate-resistant defects. 6 ECTODERM Neurulation is a fundamental event of embryogenesis distinct locations in the brain and spinal cord .By The outer of the three that culminates in the formation of the neural tube, contrast, the mechanisms that underlie the forma- embryonic (germ) layers that which is the precursor of the brain and spinal cord. A tion, elevation and fusion of the neural folds have gives rise to the entire central region of specialized dorsal ECTODERM, the neural plate, remained elusive. nervous system, plus other organs and embryonic develops bilateral neural folds at its junction with sur- An opportunity has now arisen for an incisive analy- structures. face (non-neural) ectoderm. These folds elevate, come sis of neurulation mechanisms using the growing battery into contact (appose) in the midline and fuse to create of genetically targeted and other mutant mouse strains NEURAL CREST the neural tube, which, thereafter, becomes covered by in which NTDs form part of the mutant phenotype7.At A migratory cell population that future epidermal ectoderm. -

Animal Origins and the Evolution of Body Plans 621

Animal Origins and the Evolution 32 of Body Plans In 1822, nearly forty years before Darwin wrote The Origin of Species, a French naturalist, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, was examining a lob- ster. He noticed that when he turned the lobster upside down and viewed it with its ventral surface up, its central nervous system was located above its digestive tract, which in turn was located above its heart—the same relative positions these systems have in mammals when viewed dorsally. His observations led Geoffroy to conclude that the differences between arthropods (such as lobsters) and vertebrates (such as mammals) could be explained if the embryos of one of those groups were inverted during development. Geoffroy’s suggestion was regarded as preposterous at the time and was largely dismissed until recently. However, the discovery of two genes that influence a sys- tem of extracellular signals involved in development has lent new support to Geof- froy’s seemingly outrageous hypothesis. Genes that Control Development A A vertebrate gene called chordin helps to establish cells on one side of the embryo human and a lobster carry similar genes that control the development of the body as dorsal and on the other as ventral. A probably homologous gene in fruit flies, called axis, but these genes position their body sog, acts in a similar manner, but has the opposite effect. Fly cells where sog is active systems inversely. A lobster’s nervous sys- become ventral, whereas vertebrate cells where chordin is active become dorsal. How- tem runs up its ventral (belly) surface, whereas a vertebrate’s runs down its dorsal ever, when sog mRNA is injected into an embryo (back) surface. -

Animal Phylum Poster Porifera

Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES ANNELIDA MOLLUSCA ECHINODERMATA ARTHROPODA CHORDATA Hexactinellida -- glass (siliceous) Anthozoa -- corals and sea Turbellaria -- free-living or symbiotic Polychaetes -- segmented Gastopods -- snails and slugs Asteroidea -- starfish Trilobitomorpha -- tribolites (extinct) Urochordata -- tunicates Groups sponges anemones flatworms (Dugusia) bristleworms Bivalves -- clams, scallops, mussels Echinoidea -- sea urchins, sand Chelicerata Cephalochordata -- lancelets (organisms studied in detail in Demospongia -- spongin or Hydrazoa -- hydras, some corals Trematoda -- flukes (parasitic) Oligochaetes -- earthworms (Lumbricus) Cephalopods -- squid, octopus, dollars Arachnida -- spiders, scorpions Mixini -- hagfish siliceous sponges Xiphosura -- horseshoe crabs Bio1AL are underlined) Cubozoa -- box jellyfish, sea wasps Cestoda -- tapeworms (parasitic) Hirudinea -- leeches nautilus Holothuroidea -- sea cucumbers Petromyzontida -- lamprey Mandibulata Calcarea -- calcareous sponges Scyphozoa -- jellyfish, sea nettles Monogenea -- parasitic flatworms Polyplacophora -- chitons Ophiuroidea -- brittle stars Chondrichtyes -- sharks, skates Crustacea -- crustaceans (shrimp, crayfish Scleropongiae -- coralline or Crinoidea -- sea lily, feather stars Actinipterygia -- ray-finned fish tropical reef sponges Hexapoda -- insects (cockroach, fruit fly) Sarcopterygia -- lobed-finned fish Myriapoda Amphibia (frog, newt) Chilopoda -- centipedes Diplopoda -- millipedes Reptilia (snake, turtle) Aves (chicken, hummingbird) Mammalia -

Essential Role of Non-Canonical Wnt Signalling in Neural Crest Migration Jaime De Calisto1,2, Claudio Araya1,2, Lorena Marchant1,2, Chaudhary F

Research article 2587 Essential role of non-canonical Wnt signalling in neural crest migration Jaime De Calisto1,2, Claudio Araya1,2, Lorena Marchant1,2, Chaudhary F. Riaz1 and Roberto Mayor1,2,3,* 1Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK 2Millennium Nucleus in Developmental Biology, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Casilla 653, Santiago, Chile 3Fundacion Ciencia para la Vida, Zanartu 1482, Santiago, Chile *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 8 April 2005 Development 132, 2587-2597 Published by The Company of Biologists 2005 doi:10.1242/dev.01857 Summary Migration of neural crest cells is an elaborate process that the Wnt receptor Frizzled7 (Fz7). Furthermore, loss- and requires the delamination of cells from an epithelium and gain-of-function experiments reveal that Wnt11 plays an cell movement into an extracellular matrix. In this work, it essential role in neural crest migration. Inhibition of neural is shown for the first time that the non-canonical Wnt crest migration by blocking Wnt11 activity can be rescued signalling [planar cell polarity (PCP) or Wnt-Ca2+] by intracellular activation of the non-canonical Wnt pathway controls migration of neural crest cells. By using pathway. When Wnt11 is expressed opposite its normal site specific Dsh mutants, we show that the canonical Wnt of expression, neural crest migration is blocked. Finally, signalling pathway is needed for neural crest induction, time-lapse analysis of cell movement and cell protrusion in while the non-canonical Wnt pathway is required for neural crest cultured in vitro shows that the PCP or Wnt- neural crest migration. -

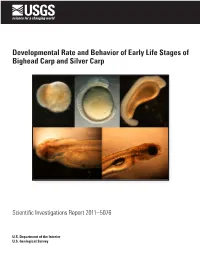

Developmental Rate and Behavior of Early Life Stages of Bighead Carp and Silver Carp

Developmental Rate and Behavior of Early Life Stages of Bighead Carp and Silver Carp Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5076 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover images. Left to right (top) silver carp embryo at morula stage, silver carp embryo at olfactory placode stage, silver carp embryo at otolith appearance stage, (bottom) silver carp larvae at gill filament stage, silver carp larvae at one-chamber gas bladder stage. Developmental Rate and Behavior of Early Life Stages of Bighead Carp and Silver Carp By Duane C. Chapman and Amy E. George Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5076 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Chapman, D.C., George, A.E., 2011, Developmental rate and behavior of early life stages of bighead carp and silver carp: U.S.