The Challenge to the South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizational Framework of the G-77

17 CHAPTER 2 ORGANIZATIONAL FRAMEWORK OF THE GROUP OF 77 by Lydia Swart …neither the Western media nor Western scholars pay much attention to the multilateral policies and practices of the states variously described as the South, the third world, or developing countries. In particular, patterns of cooperation among these states in pursuit of common interests at the UN are often ignored or dismissed as of little consequence. Sally Morphet, 2004 Institutional Arrangements: UNCTAD The institutional arrangements of the G-77 developed slowly. In its first years, the G-77’s activities primarily coalesced around UNCTAD as it was regarded by the South as the key locus to improve conditions of trade for development and to form a counterbalance to the Bretton Woods Institutions dominated by the North. The G-77 focus on UNCTAD was so pronounced that until 1976—when it held a Conference on Economic Cooperation among Developing Countries—the group only convened high-level meetings in preparation for UNCTAD sessions. These ministerial meetings to prepare for UNCTAD started in 1967 at the initiative of the Group of 31, consisting of developing countries that were members of UNCTAD’s Trade and Development Board (TDB), represented by Ambassadors in Geneva.10 The first G-77 ministerial meeting in 1967 adopted the Charter of Algiers, which details the G-77’s programme of action but is rather short on internal institutional issues. It is only at the very end of the Algiers Charter that a few organizational aspects are mentioned. The G-77 decided to meet at the ministerial level as “often as this may be deemed necessary” but “always prior to the convening of sessions” of 10 Later referred to as preparatory meetings. -

Ecreee Energy and Energy Efficiency

ECOWAS CENTRE FOR RENEWABLE ECREEE ENERGY AND ENERGY EFFICIENCY www.ecreee.org – no 7 – July 2013 highlights ECREEE RECEIVES AWARD AT MessaGE FROM THE ED P. 2 VIENNA ENERGY FORUM The ECOWAS region is now very well positioned to make the most of major developments in renewable energy and energy efficiency. ECREEE AS MODEL FOR OTHER ENERGY CENTRES P. 5 ECREEE’s activities and achievements in the sustainable energy sector have proved a success story for other sub-re- gions on the continent to emulate. HIGH LEVEL GERMAN DELEGATION VISITS ECREEE P. 9 The Vice- Minister President and Minister of Economy, Energy, Climate Protection and Territorial Planning of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, Ms Eveline Lemke ECREEE PARTICIPATES IN CWEE7 IN SHANGHAI 9 ecowas validates regional action plan Framework on clean COOKING The conference also provided a platform Besides validating the action plan framework, this regional workshop provided for the exchange of information between valuable insight into the latest on best practice and information exchange developed and developing regions on wind energy focused on issues such as the challenges regarding the proliferation of clean cooking technologies and services, ways of addressing these challenges from ECOWAS President Visits the a regional and international perspective, as well as and policy and planning ECREEE Secretariat tools that promote clean, safe and efficient cooking as a driver for economic growth and improvement of environmental and social conditions. AUSTRIA DEEPENS PARTNERSHIP WITH ECREEE The Austrian Development Agency (ADA) reinforced its existing collaboration with ECREEE, with the award of a further 2m EUR to support the implementation of the centre’s second operational phase in line with its Business Plan which ends in 2016. -

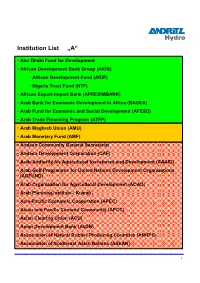

Institution List „A“

Institution List „A“ • Abu Dhabi Fund for Development • African Development Bank Group (AfDB) • African Development Fund (AfDF) • Nigeria Trust Fund (NTF) • African Export-Import Bank (AFREXIMBANK) • Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA) • Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) • Arab Trade Financing Program (ATFP) • Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) • Arab Monetary Fund (AMF) • Andean Community General Secretariat • Andean Development Corporation (CAF) • Arab Authority for Agricultural Investment and Development (AAAID) • Arab Gulf Programme for United Nations Development Organizations (AGFUND) • Arab Organization for Agricultural Development (AOAD) • Arab Planning Institute - Kuwait • Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) • Asian and Pacific Coconut Community (APCC) • Asian Clearing Union (ACU) • Asian Development Bank (AsDB) • Association of Natural Rubber Producing Countries (ANRPC) • Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 1 Institution List „B-C“ • Bank of Central African States (BEAC) • Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) • Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) • Baltic Council of Ministers • Bank for International Settlements (BIS) • Black Sea Trade and Development Bank (BSTDB) • Caribbean Centre for Monetary Studies (CCMS) • Caribbean Community (CARICOM) • Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) • Caribbean Regional Technical Assistance Centre (CARTAC) • Center for Latin American Monetary Studies (CEMLA) • Center for Marketing Information and Advisory Services for Fishery Products -

Development of Payment and Settlement System

CHAPTER 7 Development of Payment and Settlement System Khin Thida Maw This chapter should be cited as: Khin Thida Maw, 2012. “Development of Payment and Settlement System.” In Economic Reforms in Myanmar: Pathways and Prospects, edited by Hank Lim and Yasuhiro Yamada, BRC Research Report No.10, Bangkok Research Center, IDE- JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. Chapter 7 Development of Payment and Settlement System Khin Thida Maw ______________________________________________________________________ Abstract The new government of Myanmar has proved its intention to have good relations with the international community. Being a member of ASEAN, Myanmar has to prepare the requisite measures to assist in the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015. However, the legacy of the socialist era and the tight control on the banking system spurred people on to cash rather than the banking system for daily payment. The level of Myanmar’s banking sector development is further behind the standards of other regional banks. This paper utilizes a descriptive approach as it aims to provide the reader with an understanding of the current payment and settlement system of Myanmar’s financial sector and to recommend some policy issues for consideration. Section 1 introduces general background to the subject matter. Section 2 explains the existing domestic and international payment and settlement systems in use by Myanmar. Section 3 provides description of how the information has been collected and analyzed. Section 4 describes recent banking sector developments and points for further consideration relating to payment and settlement system. And Section 5 concludes with the suggestions and recommendation. ______________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction Practically speaking, Myanmar’s economy was cash-based due to the prolonged decline of the banking system after nationalization beginning in the early 1960s. -

TEMPERED LIKE STEEL the Economic Community of West African States Celebrated Its 30Th Anniversary in May, 2005

ECOWAS 30th anniversary and roughly for the same reasons: economic cooperation among of the 15 members have met the economic convergence criteria. member states and collective bargaining strength on a global level. However, it is an instrument whose time has come and it seems cer- Ecowas was an acknowledgement that despite all their differ- tain that the Eco will make its appearance in the near future. ences, the member states were essentially the same in terms of needs, One of Ecowas’ successes has been in allowing relatively free resources and aspirations. It was also an acknowledgement that the movement of people across borders. Passports or national identity integration of their relative small markets into a large regional one documents are still required but not visas. Senegal and Benin issue was essential to accelerate economic activity and therefore growth. Ecowas passports to their citizens. The founders of the organisation were just as convinced that artifi- The Ecowas Secretariat in Abuja is working on modalities to allow cial national barriers, created on old colonial maps, were cutting across document-free movement of people and goods. This might take time, ancient trade routes and patterns and that these barriers had to go. as other regulations, such as residence and establishment rights have However, this came about at a time when sub-regional organisa- to be put in place first. tions were looked on with a degree of suspicion and African coun- One of the organisation's most vital arms is Ecomog, its peace- tries, encouraged by Cold War politics, had become inward-looking keeping force. -

Saman Kelegama: Even the Blood Running Through His Veins Is Oriented to Economics

7/14/2017 Saman Kelegama: Even the blood running through his veins is oriented to economics Custom Search Search Friday Jul 14, 2017 (http s(h:/t/twp ws(h:w/t/t.pwfa:i/ct/tweebrw.ocwoo.kmft..c/lfkot/_mrs/rsdi)laainlykfat)) HOME (HTTP://WWW.FT.LK/) / COLUMNISTS (HTTP://WWW.FT.LK/COLUMNS)/ SAMAN KELEGAMA: EVEN THE BLOOD RUNNING THROUGH HIS VEINS IS ORIENTED TO ECONOMICS Saman Kelegama: Even the blood running through his veins is oriented to economics 1 Comments / 2838 Views / Tuesday, 27 June 2017 00:10 10 940 The bearded economist who saw shortcomings of Sri Lanka’s liberalisation move My association with Dr. Saman Kelegama, Executive Director of the Institute of Policy Studies or IPS, dates back to the early 1990s when I had the opportunity to listen to him at an international conference on trade liberalisation. At that time, it was a cardinal sin to pinpoint shortcomings of the trade liberalisation experiment which Sri Lanka had initiated a decade earlier, but the bearded young economist who took the podium as a researcher from IPS surprised us all. He said that the trade liberalisation move initiated by Sri Lanka in 1978 was a necessity, but the timing and the steps taken were all catastrophic. What he meant was that Sri Lanka, instead of going for a wholesale trade liberalisation, could have done it in steps so that its adverse effects could have been minimised. Since then, I became a fan of Dr. Saman Kelegama, who is known as Saman to his friends. I had a very close rapport with him, personally as well as professionally. -

South-South Cooperation: a Challenge to the Aid System?

South-South Cooperation: A Challenge to the Aid System? The Reality of Aid Special Report on South-South Cooperation 2010 The Reality of Aid South-South Cooperation: A Challenge to the Aid System? is published in the Philippines in 2010 by IBON Books, IBON Center, 114 Timog Avenue, Quezon City, 1103 Philippines [email protected] www.ibon.org Copyright @2010 by the Reality of Aid Management Committee Layout: Jennifer T. Padilla Cover Photos: unescap.com, xanthis.files.wordpress.com Printed and bound in the Philippines by IBON Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved ISBN 978-971-0483-50-1 The Reality of Aid Network The Reality of Aid (RoA) Network exists to promote national and international policies that will contribute to new and effective strategies for poverty eradication built on solidarity and equity. Established in 1993, the Reality of Aid is a collaborative non-profit initiative involving non- governmental organisations from North and South. The Reality of Aid regularly publishes reliable reports on international development cooperation and the extent to which governments, North and South, address the extreme income inequalities and structural, social and political injustices that entrench people in poverty. The Reality of Aid has been publishing its reports and Reality Checks on aid and development cooperation since 1993. The Reality of Aid Global Management Committee is made up of regional representatives of all its member-organisations. Antonio Tujan, Jr. Chairperson / Representing Asia-Pacific CSO partners IBON Foundation/Chairperson of the Steering Committee RoA-Asia-Pacific Brian Tomlinson Vice Chairperson/Representing non-European Canadian Council for International Cooperation Country CSO partners (CCIC) Vitalice Meja Representing African CSO partners Coordinator, RoA-Africa Secretariat Ruben Fernandez Representing Latin American CSO partners Asociación Latinoamericana de Organizaciones de Promoción al Desarrollo, A.C. -

Assessment of South-South Cooperation and the Global Narrative on the Eve of Bapa+40

Research Paper 88 November 2018 ASSESSMENT OF SOUTH-SOUTH COOPERATION AND THE GLOBAL NARRATIVE ON THE EVE OF BAPA+40 Yuefen LI RESEARCH PAPERS 88 ASSESSMENT OF SOUTH-SOUTH COOPERATION AND 1 THE GLOBAL NARRATIVE ON THE EVE OF BAPA+40 Yuefen LI2 SOUTH CENTRE NOVEMBER 2018 1 This paper is based on the author’s presentations at two workshops for the Group of 77 and China in August and September 2018. The author wishes to express her deep appreciation of the valuable and detailed comments from Dr. Carlos Correa, Dr. Rashmi Banga and Mr. Daniel Uribe. The views contained in this paper are attributable to the author and do not represent the institutional views of the South Centre or its Member States. Any mistake or omission in this study is the sole responsibility of the author. 2 Senior Adviser on South-South Cooperation and Development Finance, The South Centre (e-mail: [email protected]) SOUTH CENTRE In August 1995 the South Centre was established as a permanent inter- governmental organization of developing countries. In pursuing its objectives of promoting South solidarity, South-South cooperation, and coordinated participation by developing countries in international forums, the South Centre has full intellectual independence. It prepares, publishes and distributes information, strategic analyses and recommendations on international economic, social and political matters of concern to the South. The South Centre enjoys support and cooperation from the governments of the countries of the South and is in regular working contact with the Non-Aligned Movement and the Group of 77 and China. The Centre’s studies and position papers are prepared by drawing on the technical and intellectual capacities existing within South governments and institutions and among individuals of the South. -

How Feasible Is the ECO Currency? a Study of ECOWAS Business Cycles Synchronicity

RESEARCH PAPER April 2020 How Feasible Is the ECO Currency? A Study of ECOWAS Business Cycles Synchronicity Youssef EL JAI RP-20/05 About Policy Center for the New South Policy Center for the New South, formerly OCP Policy Center, is a Moroccan policy- oriented think tank based in Rabat, Morocco, striving to promote knowledge sharing and to contribute to an enriched reflection on key economic and international relations issues. By offering a southern perspective on major regional and global strategic challenges facing developing and emerging countries, the Policy Center for the New South aims to provide a meaningful policy-making contribution through its four research programs: Agriculture, Environment and Food Security, Economic and Social Development, Commodity Economics and Finance, Geopolitics and International Relations. On this basis, we are actively engaged in public policy analysis and consultation while promoting international cooperation for the development of countries in the southern hemisphere. In this regard, Policy Center for the New South aims to be an incubator of ideas and a source of forward thinking for proposed actions on public policies within emerging economies, and more broadly for all stakeholders engaged in the national and regional growth and development process. For this purpose, the Think Tank relies on independent research and a solid network of internal and external leading research fellows. One of the objectives of Policy Center for the New South is to support and sustain the emergence of wider Atlantic Dialogues and cooperation on strategic regional and global issues. Aware that achieving these goals also require the development and improvement of Human capital, we are committed through our Policy School to effectively participate in strengthening national and continental capacities, and to enhance the understanding of topics from related research areas. -

Malaysia Permanent Mission to the United Nations

MALAYSIA PERMANENT MISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS (Please check against delivery) STATEMENT BY H.E. AMBASSADOR HUSSEIN HANIFF PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF MALAYSIA TO THE UNITED NATIONS ON BEHALF OF ASEAN AT THE SECOND COMMITTEE OF THE 68th SESSION OF THE UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY, ON AGENDA ITEM 17: MACROECONOMIC POLICY QUESTIONS NEW YORK, 24 OCTOBER 2013 313 East 43rd Street Tel: (212) 986 6310 Email: [email protected] New York, NY 10017 Fax: (212) 490 8576 Website: www.un.int/malaysia Mr. Chairman, I have the honour to speak on behalf of the ten Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), namely Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. ASEAN would like to align itself with the statement delivered by the distinguished representative of Fiji on behalf of the Group of 77 and China. ASEAN would like to express its gratitude to the Secretary-General and the President of Trade and Development Board (TDB) for their reports which provide a picture on the current economic situation and interrelated issues in trade, debt and sustainable development. Mr. Chairman, 2. ASEAN’s economic performance as a whole has been resilient since recovering from the global crisis in 2008. ASEAN has continued its robust economic performance in 2012. In particular, ASEAN economies as a whole grew by 5.7 percent, which is almost one percentage point higher than the region's economic growth rate in 2011. The faster growth is noteworthy in a global environment of weaker growth performance overall. -

South-South Economic Cooperation: Motives, Problems and Possibilities

SOUTH-SOUTH ECONOMIC COOPERATION: MOTIVES, PROBLEMS AND POSSIBILITIES Amitava Krishna Dutt Department of Political Science University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA [email protected] December 2013 Over the last fifty years or so, and especially in the last decade or so, calls for increases in South- South economic cooperation and interaction have intensified with a view to promoting Southern development. This paper examines the main motives behind this call and the analytical approaches underlying them, discusses whether recent trends in South-South interaction have fulfilled the expectations of its advocates, and explores the possibilities that exist for increasing such cooperation and interaction for Southern development. Prepared for presentation at an URPE session on South-South economic integration and development at the ASSA meetings in Philadelphia, January 4, 2014. 0 1. Introduction Calls for greater South-South economic cooperation leading to more economic interaction between less- developed countries (which are collectively called the South) in trade, capital movements, technology transfers, and other spheres, have a fairly long history. Ever since the independence of many Southern countries, and the growing recognition that trade with more-developed countries, the North, South-South trade was advocated by many scholars and policymakers focused on Southern development. Recently there have been renewed calls for greater South-South cooperation and interaction, especially through the promotion of South-South trade and capital flows (see, for instance, Asian Development Bank, 2011, Thrasher and Najam, 2012). A great deal of effort has been expended by Southern countries to increase South-South interaction, with Southern governments playing an important role in promoting regional integration within the South. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners. a Copy Can Be Downlo

Taylor, Owen (2014) International law and revolution. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20343 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. INTERNATIONAL LAW AND REVOLUTION OWEN TAYLOR Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2014 Law Department SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. Signed: ____________________________ Date: _________________23/10/2014 2 ABSTRACT: This thesis aims to provide an investigation into how revolutionary transformation aimed to affect the international legal order itself, rather than what the international order might have to say about a revolution.