Student Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Drag Force Calculation

DRAG FORCE CALCULATION “Drag is the component of force on a body acting parallel to the direction of relative motion.” [1] This can occur between two differing fluids or between a fluid and a solid. In this lab, the drag force will be explored between a fluid, air, and a solid shape. Drag force is a function of shape geometry, velocity of the moving fluid over a stationary shape, and the fluid properties density and viscosity. It can be calculated using the following equation, ퟏ 푭 = 흆푨푪 푽ퟐ 푫 ퟐ 푫 Equation 1: Drag force equation using total profile where ρ is density determined from Table A.9 or A.10 in your textbook A is the frontal area of the submerged object CD is the drag coefficient determined from Table 1 V is the free-stream velocity measured during the lab Table 1: Known drag coefficients for various shapes Body Status Shape CD Square Rod Sharp Corner 2.2 Circular Rod 0.3 Concave Face 1.2 Semicircular Rod Flat Face 1.7 The drag force of an object can also be calculated by applying the conservation of momentum equation for your stationary object. 휕 퐹⃗ = ∫ 푉⃗⃗ 휌푑∀ + ∫ 푉⃗⃗휌푉⃗⃗ ∙ 푑퐴⃗ 휕푡 퐶푉 퐶푆 Assuming steady flow, the equation reduces to 퐹⃗ = ∫ 푉⃗⃗휌푉⃗⃗ ∙ 푑퐴⃗ 퐶푆 The following frontal view of the duct is shown below. Integrating the velocity profile after the shape will allow calculation of drag force per unit span. Figure 1: Velocity profile after an inserted shape. Combining the previous equation with Figure 1, the following equation is obtained: 푊 퐷푓 = ∫ 휌푈푖(푈∞ − 푈푖)퐿푑푦 0 Simplifying the equation, you get: 20 퐷푓 = 휌퐿 ∑ 푈푖(푈∞ − 푈푖)훥푦 푖=1 Equation 2: Drag force equation using wake profile The pressure measurements can be converted into velocity using the Bernoulli’s equation as follows: 2Δ푃푖 푈푖 = √ 휌퐴푖푟 Be sure to remember that the manometers used are in W.C. -

Chapter 4: Immersed Body Flow [Pp

MECH 3492 Fluid Mechanics and Applications Univ. of Manitoba Fall Term, 2017 Chapter 4: Immersed Body Flow [pp. 445-459 (8e), or 374-386 (9e)] Dr. Bing-Chen Wang Dept. of Mechanical Engineering Univ. of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, R3T 5V6 When a viscous fluid flow passes a solid body (fully-immersed in the fluid), the body experiences a net force, F, which can be decomposed into two components: a drag force F , which is parallel to the flow direction, and • D a lift force F , which is perpendicular to the flow direction. • L The drag coefficient CD and lift coefficient CL are defined as follows: FD FL CD = 1 2 and CL = 1 2 , (112) 2 ρU A 2 ρU Ap respectively. Here, U is the free-stream velocity, A is the “wetted area” (total surface area in contact with fluid), and Ap is the “planform area” (maximum projected area of an object such as a wing). In the remainder of this section, we focus our attention on the drag forces. As discussed previously, there are two types of drag forces acting on a solid body immersed in a viscous flow: friction drag (also called “viscous drag”), due to the wall friction shear stress exerted on the • surface of a solid body; pressure drag (also called “form drag”), due to the difference in the pressure exerted on the front • and rear surfaces of a solid body. The friction drag and pressure drag on a finite immersed body are defined as FD,vis = τwdA and FD, pres = pdA , (113) ZA ZA Streamwise component respectively. -

Sept. 12, 1950 W

Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2 Sheets-Sheet. INVENTOR. M/2 2.7aar alwg,57. A77OAMA). Sept. 12, 1950 W. ANGST 2,522,337 MACH METER Filed Dec. 9, 1944 2. Sheets-Sheet 2 N 2 2 %/ NYSASSESSN S2,222,W N N22N \ As I, mtRumaIII-m- III It's EARAs i RNSITIE, 2 72/ INVENTOR, M247 aeawosz. "/m2.ATTORNEY. Patented Sept. 12, 1950 2,522,337 UNITED STATES ; :PATENT OFFICE 2,522,337 MACH METER Walter Angst, Manhasset, N. Y., assignor to Square D Company, Detroit, Mich., a corpora tion of Michigan Application December 9, 1944, Serial No. 567,431 3 Claims. (Cl. 73-182). is 2 This invention relates to a Mach meter for air plurality of posts 8. Upon one of the posts 8 are craft for indicating the ratio of the true airspeed mounted a pair of serially connected aneroid cap of the craft to the speed of sound in the medium sules 9 and upon another of the posts 8 is in which the aircraft is traveling and the object mounted a diaphragm capsuler it. The aneroid of the invention is the provision of an instrument s: capsules 9 are sealed and the interior of the cas-l of this type for indicating the Mach number of an . ing is placed in communication with the static aircraft in fight. opening of a Pitot static tube through an opening The maximum safe Mach number of any air in the casing, not shown. The interior of the dia craft is the value of the ratio of true airspeed to phragm capsule is connected through the tub the speed of sound at which the laminar flow of ing 2 to the Pitot or pressure opening of the Pitot air over the wings fails and shock Waves are en static tube through the opening 3 in the back countered. -

The Difference Between Higher and Lower Flap Setting Configurations May Seem Small, but at Today's Fuel Prices the Savings Can Be Substantial

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HIGHER AND LOWER FLAP SETTING CONFIGURATIONS MAY SEEM SMALL, BUT AT TODAY'S FUEL PRICES THE SAVINGS CAN BE SUBSTANTIAL. 24 AERO QUARTERLY QTR_04 | 08 Fuel Conservation Strategies: Takeoff and Climb By William Roberson, Senior Safety Pilot, Flight Operations; and James A. Johns, Flight Operations Engineer, Flight Operations Engineering This article is the third in a series exploring fuel conservation strategies. Every takeoff is an opportunity to save fuel. If each takeoff and climb is performed efficiently, an airline can realize significant savings over time. But what constitutes an efficient takeoff? How should a climb be executed for maximum fuel savings? The most efficient flights actually begin long before the airplane is cleared for takeoff. This article discusses strategies for fuel savings But times have clearly changed. Jet fuel prices fuel burn from brake release to a pressure altitude during the takeoff and climb phases of flight. have increased over five times from 1990 to 2008. of 10,000 feet (3,048 meters), assuming an accel Subse quent articles in this series will deal with At this time, fuel is about 40 percent of a typical eration altitude of 3,000 feet (914 meters) above the descent, approach, and landing phases of airline’s total operating cost. As a result, airlines ground level (AGL). In all cases, however, the flap flight, as well as auxiliarypowerunit usage are reviewing all phases of flight to determine how setting must be appropriate for the situation to strategies. The first article in this series, “Cost fuel burn savings can be gained in each phase ensure airplane safety. -

Aerodynamic Characteristics of Naca 0012 Airfoil Section at Different Angles of Attack

AERODYNAMIC CHARACTERISTICS OF NACA 0012 AIRFOIL SECTION AT DIFFERENT ANGLES OF ATTACK SUPREETH NARASIMHAMURTHY GRADUATE STUDENT 1327291 Table of Contents 1) Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1 2) Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 3) Results……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………......5 4) Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..9 5) References…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………10 List of Figures Figure 1: Basic nomenclature of an airfoil………………………………………………………………………………………………...1 Figure 2: Computational domain………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Figure 3: Static Pressure Contours for different angles of attack……………………………………………………………..5 Figure 4: Velocity Magnitude Contours for different angles of attack………………………………………………………………………7 Fig 5: Variation of Cl and Cd with alpha……………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Figure 6: Lift Coefficient and Drag Coefficient Ratio for Re = 50000…………………………………………………………8 List of Tables Table 1: Lift and Drag coefficients as calculated from lift and drag forces from formulae given above……7 Introduction It is a fact of common experience that a body in motion through a fluid experience a resultant force which, in most cases is mainly a resistance to the motion. A class of body exists, However for which the component of the resultant force normal to the direction to the motion is many time greater than the component resisting the motion, and the possibility of the flight of an airplane depends on the use of the body of this class for wing structure. Airfoil is such an aerodynamic shape that when it moves through air, the air is split and passes above and below the wing. The wing’s upper surface is shaped so the air rushing over the top speeds up and stretches out. This decreases the air pressure above the wing. The air flowing below the wing moves in a comparatively straighter line, so its speed and air pressure remain the same. -

No Acoustical Change” for Propeller-Driven Small Airplanes and Commuter Category Airplanes

4/15/03 AC 36-4C Appendix 4 Appendix 4 EQUIVALENT PROCEDURES AND DEMONSTRATING "NO ACOUSTICAL CHANGE” FOR PROPELLER-DRIVEN SMALL AIRPLANES AND COMMUTER CATEGORY AIRPLANES 1. Equivalent Procedures Equivalent Procedures, as referred to in this AC, are aircraft measurement, flight test, analytical or evaluation methods that differ from the methods specified in the text of part 36 Appendices A and B, but yield essentially the same noise levels. Equivalent procedures must be approved by the FAA. Equivalent procedures provide some flexibility for the applicant in conducting noise certification, and may be approved for the convenience of an applicant in conducting measurements that are not strictly in accordance with the 14 CFR part 36 procedures, or when a departure from the specifics of part 36 is necessitated by field conditions. The FAA’s Office of Environment and Energy (AEE) must approve all new equivalent procedures. Subsequent use of previously approved equivalent procedures such as flight intercept typically do not need FAA approval. 2. Acoustical Changes An acoustical change in the type design of an airplane is defined in 14 CFR section 21.93(b) as any voluntary change in the type design of an airplane which may increase its noise level; note that a change in design that decreases its noise level is not an acoustical change in terms of the rule. This definition in section 21.93(b) differs from an earlier definition that applied to propeller-driven small airplanes certificated under 14 CFR part 36 Appendix F. In the earlier definition, acoustical changes were restricted to (i) any change or removal of a muffler or other component of an exhaust system designed for noise control, or (ii) any change to an engine or propeller installation which would increase maximum continuous power or propeller tip speed. -

UNIT – 4 FORCES on IMMERSED BODIES Lecture-01

1 UNIT – 4 FORCES ON IMMERSED BODIES Lecture-01 Forces on immersed bodies When a body is immersed in a real fluid, which is flowing at a uniform velocity U, the fluid will exert a force on the body. The total force (FR) can be resolved in two components: 1. Drag (FD): Component of the total force in the direction of motion of fluid. 2. Lift (FL): Component of the total force in the perpendicular direction of the motion of fluid. It occurs only when the axis of the body is inclined to the direction of fluid flow. If the axis of the body is parallel to the fluid flow, lift force will be zero. Expression for Drag & Lift Forces acting on the small elemental area dA are: i. Pressure force acting perpendicular to the surface i.e. p dA ii. Shear force acting along the tangential direction to the surface i.e. τ0dA (a) Drag force (FD) : Drag force on elemental area = p dAcosθ + τ0 dAcos(90 – θ = p dAosθ + τ0dAsinθ Hence Total drag (or profile drag) is given by, Where �� = ∫ � cos � �� + ∫�0 sin � �� = pressure drag or form drag, and ∫ � cos � �� = shear drag or friction drag or skin drag (b) Lift0 force (F ) : ∫ � sin � ��L Lift force on the elemental area = − p dAsinθ + τ0 dA sin(90 – θ = − p dAsiθ + τ0dAcosθ Hence, total lift is given by http://www.rgpvonline.com �� = ∫�0 cos � �� − ∫ p sin � �� 2 The drag & lift for a body moving in a fluid of density at a uniform velocity U are calculated mathematically as 2 � And �� = � � � 2 � Where A = projected area of the body or�� largest= � project� � area of the immersed body. -

16.00 Introduction to Aerospace and Design Problem Set #3 AIRCRAFT

16.00 Introduction to Aerospace and Design Problem Set #3 AIRCRAFT PERFORMANCE FLIGHT SIMULATION LAB Note: You may work with one partner while actually flying the flight simulator and collecting data. Your write-up must be done individually. You can do this problem set at home or using one of the simulator computers. There are only a few simulator computers in the lab area, so not leave this problem to the last minute. To save time, please read through this handout completely before coming to the lab to fly the simulator. Objectives At the end of this problem set, you should be able to: • Take off and fly basic maneuvers using the flight simulator, and describe the relationships between the control yoke and the control surface movements on the aircraft. • Describe pitch - airspeed - vertical speed relationships in gliding performance. • Explain the difference between indicated and true airspeed. • Record and plot airspeed and vertical speed data from steady-state flight conditions. • Derive lift and drag coefficients based on empirical aircraft performance data. Discussion In this lab exercise, you will use Microsoft Flight Simulator 2000/2002 to become more familiar with aircraft control and performance. Also, you will use the flight simulator to collect aircraft performance data just as it is done for a real aircraft. From your data you will be able to deduce performance parameters such as the parasite drag coefficient and L/D ratio. Aircraft performance depends on the interplay of several variables: airspeed, power setting from the engine, pitch angle, vertical speed, angle of attack, and flight path angle. -

Emergency Procedures C172

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES NON CRITICAL ACTION June 2015 1. Maintain aircraft control. Table of Contents 2. Analyze the situation and take proper action. C 172 3.Land as soon as conditions permit NON CRITICAL ACTION PROCEDURES E-2 GROUND OPERATION EMERGENCIES GROUND OPERATION EMERGENCIES E-2 Emergency Engine Shutdown on the Ground Emergency Engine Shutdown on the Ground E-2 1. FUEL SELECTOR -------------------------------- OFF Engine Fire During Start E-2 2. MIXTURE ---------------------------- IDLE CUTOFF TAKEOFF EMERGENCIES E-2 3. IGNITION ------------------------------------------ OFF Abort E-2 4. MASTER SWITCH ------------------------------- OFF IN-FLIGHT EMERGENCIES E-3 Engine Failure Immediately After T/O E-3 Engine Fire during Start Engine Failure In Flt - Forced Landing E-3 If Engine starts Engine Fire During Flight E-4 1. POWER ------------------------------------- 1700 RPM Emergency Descent E-4 2. ENGINE -------------------------------- SHUTDOWN Electrical Fire/High Ammeter E-4 If Engine fails to start Negative Ammeter Reading E-4 1. CRANKING ----------------------------- CONTINUE Smoke and Fume Elimination E-5 2. MIXTURE --------------------------- IDLE CUT-OFF Oil System Malfunction E-4 3 THROTTLE ----------------------------- FULL OPEN Structural Damage or Controllability Check E-5 4. ENGINE -------------------------------- SHUTDOWN Recall E-6 FUEL SELECTOR ------ OFF Lost Procedures E-6 IGNITION SWITCH --- OFF Radio Failure E-7 MASTER SWITCH ----- OFF Diversions E-8 LANDING EMERGENCIES E-9 TAKEOFF EMERGENCIES Landing with flat tire E-9 ABORT E-9 LIGHT SIGNALS 1. THROTTLE -------------------------------------- IDLE 2. BRAKES ----------------------------- AS REQUIRED E-2 E-1 IN-FLIGHT EMERGENCIES Engine Fire During Flight Engine Failure Immediately After Takeoff 1. FUEL SELECTOR --------------------------------------- OFF 1. BEST GLIDE ------------------------------------ ESTABLISH 2. MIXTURE------------------------------------ IDLE CUTOFF 2. FUEL SELECTOR ----------------------------------------- OFF 3. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

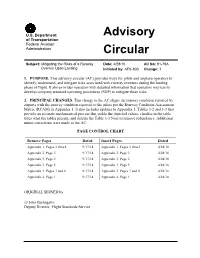

AC 91-79A CHG 1 Appendix 1 APPENDIX 1

U.S. Department Advisory of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Circular Subject: Mitigating the Risks of a Runway Date: 4/28/16 AC No: 91-79A Overrun Upon Landing Initiated by: AFS-800 Change: 1 1. PURPOSE. This advisory circular (AC) provides ways for pilots and airplane operators to identify, understand, and mitigate risks associated with runway overruns during the landing phase of flight. It also provides operators with detailed information that operators may use to develop company standard operating procedures (SOP) to mitigate those risks. 2. PRINCIPAL CHANGES. This change to the AC aligns the runway condition reported by airports with the runway condition reported to the pilots per the Runway Condition Assessment Matrix (RCAM) in Appendix 1. It also includes updates to Appendix 3, Tables 3-2 and 3-3 that provide an accurate mathematical process that yields the depicted values, clarifies in the table titles what the tables present, and deletes the Table 3-3 Note to remove redundancy. Additional minor corrections were made to the AC. PAGE CONTROL CHART Remove Pages Dated Insert Pages Dated Appendix 1, Pages 1 thru 4 9/17/14 Appendix 1, Pages 1 thru 3 4/28/16 Appendix 2, Page 2 9/17/14 Appendix 2, Page 2 4/28/16 Appendix 3, Page 2 9/17/14 Appendix 3, Page 2 4/28/16 Appendix 3, Page 5 9/17/14 Appendix 3, Page 5 4/28/16 Appendix 3, Pages 7 and 8 9/17/14 Appendix 3, Pages 7 and 8 4/28/16 Appendix 4, Page 1 9/17/14 Appendix 4, Page 1 4/28/16 ORIGINAL SIGNED by /s/ John Barbagallo Deputy Director, Flight Standards Service U.S.