THE HISTORY of MEMBERSHIP and CERTIFICATION in the APSAA: Old Demons, New Debates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin No. 65 (2019-2020)

The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis & Psychology Bulletin No. 65 (2019-2020) Programs Of Psychoanalytic Training based on the conviction that the study of lives in depth provides the best foundation for all forms of psychotherapy and for research into difficulties in living. Founded 1943 Harry Stack Sullivan, M.D., 1892-1949 Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, M.D., 1889-1957 Clara Thompson, M.D., 1893-1958 Janet Rioch Bard, M.D., 1905-1974 Erich Fromm, Ph.D., 1900-1980 David McK. Rioch, M.D., 1900-1985 COUNCIL OF FELLOWS Jacqueline Ferraro, D.M.H., Chair Emeriti: Janet Jeppson, . (Deseased) Cynthia Field, Ph.D. Anna M Antonovsky, Ph.D. Bernard Gertler, Ph.D. Lawrence Brown, Ph.D. Judy Goldberg, Ph.D. .Jay S. Kwawer, Ph.D. Evelyn Hartman, Ph.D. Edgar A. Levenson, M.D. David E. Koch, Ph.D. Carola Mann, Ph.D. Susan Kolod, Ph.D. Dale Ortmeyer, Ph.D. Robert Langan, Ph.D. Miltiades L.Zaphiropoulos, M.D. (deceased) Suzanne Little, Ph.D. Ruth Imber, Ph.D. Pasqual Pantone, Ph.D. Marcelo Rubin, Ph.D. Active: Cleonie V. White, Ph.D. Miri Abramis, Ph.D. Stefan Zicht, Ph.D. Toni Andrews, Ph.D. Seth Aronson, Ph.D. Max Belkin, Ph.D Mark Blechner, Ph.D. Susan Fabrick, M.A., L.C.S.W. The following Fellows have been awarded The Edith Seltzer Alt Distinguished Service Award in recognition of their extraordinary contributions, over many years, to the Council of Fellows, to the White Institute and to the professional community. Mrs. Edith Alt 1980 Ralph M. Crowley, M.D. -

The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis & Psychology

The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis & Psychology Bulletin No. 60 (2012 – 2013) Programs Of Psychoanalytic Training based on the conviction that the study of lives in depth provides the best foundation for all forms of psychotherapy and for research into difficulties in living. Founded 1943 Harry Stack Sullivan, M.D., 1892-1949 Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, M.D., 1889-1957 Clara Thompson, M.D., 1893-1958 Janet Rioch Bard, M.D., 1905-1974 Erich Fromm, Ph.D., 1900-1980 David McK. Rioch, M.D., 1900-1985 COUNCIL OF FELLOWS Lori Caplovitz Bohm, Ph.D., Chair Emeriti: Cynthia Field, Ph.D. Anna M. Antonovsky, Ph.D. Judith Goldberg, Ph.D. Janet Jeppson, M.D. Anton Hart, Ph.D. Edgar A. Levenson, M.D. Ruth Imber, Ph.D. Carola Mann, Ph.D. Elizabeth K. Krimendahl, Psy.D. Dale Ortmeyer, Ph.D. Jay S. Kwawer, Ph.D. Miltiades Zaphiropoulos, M.D. Paul Lippmann, Ph.D. Gilead Nachmani, Ph.D. Active: Maria Nardone, Ph.D. Seth Aronson, Psy.D. Pasqual Pantone, Ph.D. Grant H. Brenner, M.D. Jean Petrucelli, Ph.D. Lawrence Brown, Ph.D. Marcelo Rubin, Ph.D. Jacqueline Ferraro, D.M.H. Donnel B. Stern, Ph.D. The following Fellows have been awarded The Edith Seltzer Alt Distinguished Service Award in recognition of their extraordinary contributions, over many years, to the Council of Fellows, to the White Institute and to the professional community. Mrs. Edith Alt 1980 Ralph M. Crowley, M.D. 1980 Edward S. Tauber, M.D. 1985 Rose Spiegel, M.D. 1986 Ruth Moulton, M.D. 1987 John L. -

CIRCULAR LETTER #597 Pre-Meeting Spring

CIRCULAR LETTER #597 Pre-Meeting Spring MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT MARCH 2006 Dear Colleagues: Our Spring Meeting is fast approaching and I hope it is as successful as our 60th Anniversary meeting was. This will be a very unusual meeting because the Board has planned for a strategic planning meeting to take place on Thursday, which will include the Board and the Steering Committee, to take a good look at the organization and to try to figure out the direction of GAP for the next decade. I am sure the entire organization will be buzzing about the “retreat” and everyone will get a chance to voice their opinion and views over the next few months. There are many members who love the organization and find it to be one of the few places where small groups of psychiatrists gather to work on areas of our specialty that need further exploration and explication. We are laid back and yet quite intense, creative, and still product oriented with a deep sense of comradeship, fun loving and still determined to make a mark. There is truly no other psychiatric organization like it in the world. Work in between meetings has picked up and you will hear that we have a lot of good work in the pipeline and our decision to move beyond books to other forms of publication and other media is in keeping with the new electronic age that many of us have, reluctantly, been schlepped into (at least it feels that way to me). In the last few years we have used the term “think tank” more and more frequently and that means we want to use our meetings to think out of the box, to be creative and develop new ideas, to enter new territories, and to truly believe that nothing is off limits. -

PSYCHOANALYST Quarterly Magazine of the American Psychoanalytic Association

the WINTER/SPRING 2015 AMERICAN Volume 49, No . 1 PSYCHOANALYST Quarterly Magazine of The American Psychoanalytic Association Historic Moment for APsaA: INSIDE TAP… The William Alanson White Institute Election Results . 4 Mark D. Smaller Thursday, January 15, 2015, will remain a disappointment with APsaA for its exclu- National Meeting historic day for the American Psychoanalytic sionary policies. in NYC . 6–10 Association and the William Alanson White As some might not be aware, during the Institute (WAW). It was on that day APsaA’s 1950s APsaA attempted to marginalize lead- Beginnings Executive Council voted unanimously to ers and teachers of the WAW. It was not approve the WAW Society becoming an until a lawsuit, based on restraint of trade, and Endings . 12 APsaA affiliate society. Two days before, 61 was threatened by the WAW, that APsaA new WAW members were approved for backed away from these misguided actions. Annual Meeting membership by the Membership Require- The WAW was aided by legal counsel Abe in San Francisco . 24 ments and Review Committee. One day Fortas, former Supreme Court justice and a before, during the meeting of our Board on former WAW board trustee. Professional Standards, BOPS approved a The WAW was founded in 1943 in reac- Seventh Annual revised version of the APsaA Training Stan- tion to exclusionary policies of American Art Exhibit . 26 dards to include the WAW training model. psychoanalysis. As Jay Kwawer, WAW direc- As I said to members of the WAW a year tor writes, the WAW was: before during a WAW “town meeting,” APsaA’s invitation to the WAW to join us …a revolutionary alter- was probably 70 years overdue. -

Smith Ely Jelliffe

Smith Ely Jelliffe Smith Ely Jelliffe Smith Ely Jelliffe (1866-1945). American neurologist, psychiatrist, and psychoanalyst who lived and practiced in New York City nearly his entire life. Originally trained in botany and pharmacy, Jelliffe switched first to neurology in the mid-1890s then to psychiatry, neuropsychiatry, and ultimately to psychoanalysis. He received his M.D. from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University. Dr. Jelliffe was the Clinical Professor of Mental Diseases at Fordham University, president of the New York Psychiatric Society, the New York Neurological Society, and the American Psychopathological Association, and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. He was also a corresponding member of the French and Brazilian neurological societies and author of more than four hundred articles. His book, The Modern Treatment of Nervous and Mental Diseases, which he co-authored with William White, has been a classic in the field, with many reprintings. Dr. Jelliffe founded Psychoanalytic Review, the first English-language publication devoted to psychoanalysis. In it, he wrote a number of articles on psychoanalytic technique, daydreams, and transference. Dr. Jelliffe is also credited with important contributions in the field of psychosomatic medicine. These were collected in his Sketches in Psychosomatic Medicine. One of the earliest Freudian adherents in the United States, Jelliffe (with the aid of his rarely attributed first wife, Helena Leeming Jelliffe, who died in 1916) produced after the turn-of- the-century numerous translations of European works in psychopathology, neurology, psychiatry, and psychotherapy. From about 1902 he owned and edited for the next forty years the influential Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. -

The Prescient Librarian: Ilse Bry and "Sociobibliography"

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln Summer 2019 The rP escient Librarian: Ilse Bry and "Sociobibliography" Ellen D. Gilbert [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Gilbert, Ellen D., "The rP escient Librarian: Ilse Bry and "Sociobibliography"" (2019). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 2678. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2678 The Prescient Librarian: Ilse Bry and “Sociobibliography” Ellen D. Gilbert, Princeton, NJ 08540, [email protected] Abstract In the 1960s, before computers enabled people to combine myriad terms in a single search and “interdisciplinary research” was just coming into vogue, Ilse Bry (1905-1974), a German-born émigré librarian working in New York City suggested that the lines between the behavioral sciences and individual disciplines were not as rigidly drawn as was assumed. With this in mind, she founded the Mental Health Book Review Index (1956-1974), compiling and making sense of book reviews from some 255 journals that, she believed, signaled trends in literature and the discovery of new knowledge. The essays she wrote for each issue were remarkable for their breadth of literary knowledge and appreciation of bibliographic applications. In 1977 Bry’s writings were compiled in a book, The Emerging Field of Sociobibliography.(Afflerbach) Figure 1. Ilse Bry in an undated photo before she left Germany. (Reproduced from Stern, 1976) As a young woman, Bry studied philosophy in Berlin, Munich, and Vienna, Austria, where she received her Ph.D. -

B29254747.Pdf

Copyright Undertaking This thesis is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. By reading and using the thesis, the reader understands and agrees to the following terms: 1. The reader will abide by the rules and legal ordinances governing copyright regarding the use of the thesis. 2. The reader will use the thesis for the purpose of research or private study only and not for distribution or further reproduction or any other purpose. 3. The reader agrees to indemnify and hold the University harmless from and against any loss, damage, cost, liability or expenses arising from copyright infringement or unauthorized usage. IMPORTANT If you have reasons to believe that any materials in this thesis are deemed not suitable to be distributed in this form, or a copyright owner having difficulty with the material being included in our database, please contact [email protected] providing details. The Library will look into your claim and consider taking remedial action upon receipt of the written requests. Pao Yue-kong Library, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong http://www.lib.polyu.edu.hk AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF THE SUBJECTIVE TRAUMATIC SCHOOL BULLYING EXPERIENCES OF ADOLESCENT VICTIMS WHO HAVE LATER DEVELOPED EARLY PSYCHOSIS WONG MEI KWAN ROSETTA Ph.D The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 2016 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of Applied Social Sciences An exploratory study of the subjective traumatic school bullying experiences of adolescent victims who have later developed early psychosis Wong Mei-kwan Rosetta A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it reproduces no material previously published or written, nor material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

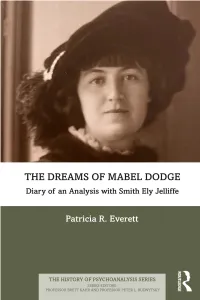

The Dreams of Mabel Dodge; Diary of an Analysis with Smith Ely Jelliffe

The Dreams of Mabel Dodge “History comes alive, as we are drawn into the dream life of Mabel Dodge, an articulate woman who played a significant role in the history of psycho- analysis in America. It is 1916 and we listen as she recounts dreams and associations to her analyst, Smith Ely Jelliffe, and he responds. Through impeccable scholarship and priceless historical documentation, Patricia Everett contextualizes a psychoanalytic adventure. Unconscious meets con- scious, patient meets analyst, and reader meets author, as this fascinating story unfolds. Patricia Everett gives us privileged access to their exciting, spirited, even thrilling interplay as they explore a realm of dreams.” — Sandra Buechler, PhD, Training and Supervising Analyst at the William Alanson White Institute, author of Psychoanalytic Approaches to Problems in Living (Routledge, 2019) “If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I’d find it hard to believe that such a book actually exists. Everett presents us with the dreams of Mabel Dodge, recorded during her analysis with Smith Ely Jelliffe, one of the most influ- ential and creative of the first American psychoanalysts. We are whisked, as if by a time machine, deep into a lost world of a century ago. And what is revealed is the inner life of an extraordinary woman, the contours of the American avant-garde, of which she was a central figure, and the workings of psychoanalysis in an early, crucial period of its history.” —James William Anderson, PhD, Professor of Clinical Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University In 1916, salon host Mabel Dodge entered psychoanalysis with Smith Ely Jelliffe in New York, recording 142 dreams during her six-month treat- ment. -

The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis & Psychology

The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis & Psychology Bulletin No. 59 (2011 – 2012) Programs Of Psychoanalytic Training based on the conviction that the study of lives in depth provides the best foundation for all forms of psychotherapy and for research into difficulties in living. Founded 1943 Harry Stack Sullivan, M.D., 1892-1949 Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, M.D., 1889-1957 Clara Thompson, M.D., 1893-1958 Janet Rioch Bard, M.D., 1905-1974 Erich Fromm, Ph.D., 1900-1980 David McK. Rioch, M.D., 1900-1985 COUNCIL OF FELLOWS Susan Kolod, Ph.D., Chair Emeriti: Jacqueline Ferraro, D.M.H. Anna M. Antonovsky, Ph.D. Judith Goldberg, Ph.D. Janet Jeppson, M.D. Anton Hart, Ph.D. Edgar A. Levenson, M.D. Ruth Imber, Ph.D. Dale Ortmeyer, Ph.D. Elizabeth K. Krimendahl, Psy.D. Miltiades Zaphiropoulos, M.D. Jay S. Kwawer, Ph.D. Robert Langan, Ph.D. Active: Paul Lippmann, Ph.D. Seth Aronson, Psy.D. Carola Mann, Ph.D. Mark Blechner, Ph.D. Karen Marisak, Ph.D. Lori Bohm, Ph.D. Gilead Nachmani, Ph.D. Joerg Bose, M.D. Maria Nardone, Ph.D. Grant H. Brenner, M.D. Pasqual Pantone, Ph.D. Lawrence Brown, Ph.D. Jean Petrucelli, Ph.D. The following Fellows have been awarded The Edith Seltzer Alt Distinguished Service Award in recognition of their extraordinary contributions, over many years, to the Council of Fellows, to the White Institute and to the professional community. Mrs. Edith Alt 1980 Ralph M. Crowley, M.D. 1980 Edward S. Tauber, M.D. 1985 Rose Spiegel, M.D. 1986 Ruth Moulton, M.D. -

Reckoning / Foresight

RECKONING / FORESIGHT MARCH 18-21, 2020 40TH ANNUAL SPRING MEETING GRAND HYATT NEW YORK TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors.............................................................4 Conference Organizers ....................................................5 General Conference Information ......................................7 Welcome Message ...........................................................8 Special Events ................................................................10 List of Division Committees and Sections ...................... 11 Continuing Education Information ..................................12 Pre-Conference Workshops ...........................................13 Keynotes.........................................................................16 Conference Programs Wednesday ..........................................................13 Thursday ..............................................................18 Friday. ..................................................................41 Saturday ..............................................................58 Award Recipients ............................................................32 Poster Presentations. .....................................................36 Hotel Maps .....................................................................80 List of Presenters............................................................83 MARK YOUR CALENDARS NOW! SPPP 2021 SPRING MEETING April 14 - 17, 2021 Chicago, IL division39springmeeting.net / MARCH 18-21, 2020 / GRAND -

Concept, in Her Example, and in Her Vision. the Story of the White

REVOLUTION WITHIN PSYCHOANALYSIS: A HISTORY OF THE WILLIAM ALANSON WHITE INSTITUTE 1 by Ralph M. Crowley, M.D. and Maurice R. Green, M.D. The Institute began with Clara Thompson's vision and the people she attracted to her vision, not only of psychoanalysis but of life. So we must understand what her vision was in order to understand the be ginnings of the Institute. Her vision is well expressed in an unpublished paper written in 1947 entitled "Anxiety and Social Standards", in which she discusses definitions of maturity and goals in therapy. In contrast with the concept of a mature man as one who adjusts to his culture, Thompson defined the mature man as a "person sufficiently anxiety-free to be able to deviate from the culture when he finds it nec essary to maintain his integrity or when he is convinced that the aims of the culture are bad for man." on or publication of She believed that the goal in therapy and analysis "is not suc cessful conformity but successful fulfillment of what is best for man." This meant that a person in a destructive culture may have to be a deviant, or in a less destructive culture a revolutionary. personal use only. Citati Clara Thompson was an example of this type of maturity and those rums. Nutzung nur für persönliche Zwecke. who associated themselves with her shared, in varying degrees, in this concept, in her example, and in her vision. The story of the White tten permission of the copyright holder. Institute begins and continues with Clara and her beliefs in "what is best for man." In the spring of 1943, Clara Thompson, Erich Fromm, David Rioch, Janet Rioch, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann and Harry Stack Sullivan made a be ginning of a new teaching and training facility. -

The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis & Psychology

The William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry, Psychoanalysis & Psychology Bulletin No. 63 (2016 – 2017) Programs Of Psychoanalytic Training based on the conviction that the study of lives in depth provides the best foundation for all forms of psychotherapy and for research into difficulties in living. Founded 1943 Harry Stack Sullivan, M.D., 1892-1949 Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, M.D., 1889-1957 Clara Thompson, M.D., 1893-1958 Janet Rioch Bard, M.D., 1905-1974 Erich Fromm, Ph.D., 1900-1980 David McK. Rioch, M.D., 1900-1985 COUNCIL OF FELLOWS Maria Nardone, Ph.D., Chair Emeriti: Jacqueline Ferraro, D.M.H. Anna M. Antonovsky, Ph.D. Cynthia Field, Ph.D. Lawrence Brown, Ph.D. Susanne Fabrick, L.C.S.W Janet Jeppson, M.D. Bernard Gertler, Ph.D. Jay S. Kwawer, Ph.D. Ruth Imber, Ph.D. Edgar A. Levenson, M.D. David E. Koch, Ph.D. Carola Mann, Ph.D. Sue Kolod, Ph.D. Dale Ortmeyer, Ph.D. Sharon Kofman, Ph.D. Miltiades L.Zaphiropoulos, M.D. (deceased) Robert Langan, Ph.D. Suzanne Little, Ph.D. Active: Maria Nardone, Ph.D. Miri Abramis, Ph.D. Jean Petrucelli, Ph.D. Lori Bohm, Ph.D. Marcelo Rubin, Ph.D. Susan Fabrick, L.C.S.W. Donnel B. Stern, Ph.D. Kenneth Eisold, Ph.D. Cleonie V. White, Ph.D. The following Fellows have been awarded The Edith Seltzer Alt Distinguished Service Award in recognition of their extraordinary contributions, over many years, to the Council of Fellows, to the White Institute and to the professional community. Mrs. Edith Alt 1980 Ralph M.