ORAL HISTORY of STANLEY TIGERMAN Interviewed by Betty J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture

1 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture Fall 2011 Contents “Permanent Change” symposium review by Brennan Buck 2 David Chipperfield in Conversation Anne Tyng: Inhabiting Geometry 4 Grafton Architecture: Shelley McNamara exhibition review by Alicia Imperiale and Yvonne Farrell in Conversation New Users Group at Yale by David 6 Agents of Change: Geoff Shearcroft and Sadighian and Daniel Bozhkov Daisy Froud in Conversation Machu Picchu Artifacts 7 Kevin Roche: Architecture as 18 Book Reviews: Environment exhibition review by No More Play review by Andrew Lyon Nicholas Adams Architecture in Uniform review by 8 “Thinking Big” symposium review by Jennifer Leung Jacob Reidel Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern 10 “Middle Ground/Middle East: Religious review by Enrique Ramirez Sites in Urban Contexts” symposium Pride in Modesty review by Britt Eversole review by Erene Rafik Morcos 20 Spring 2011 Lectures 11 Commentaries by Karla Britton and 22 Spring 2011 Advanced Studios Michael J. Crosbie 23 Yale School of Architecture Books 12 Yale’s MED Symposium and Fab Lab 24 Faculty News 13 Fall 2011 Exhibitions: Yale Urban Ecology and Design Lab Ceci n’est pas une reverie: In Praise of the Obsolete by Olympia Kazi The Architecture of Stanley Tigerman 26 Alumni News Gwathmey Siegel: Inspiration and New York Dozen review by John Hill Transformation See Yourself Sensing by Madeline 16 In The Field: Schwartzman Jugaad Urbanism exhibition review by Tributes to Douglas Garofalo by Stanley Cynthia Barton Tigerman and Ed Mitchell 2 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 David Chipperfield David Chipperfield Architects, Neues Museum, façade, Berlin, Germany 1997–2009. -

Aspects of Architectural Drawings in the Modern Era

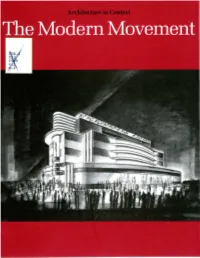

Acknowledgments Fellows of the Program (h Architecture Society 1oiLl13l I /113'1 l~~g \JI ) C,, '"l.,. This exhibition of drawings by European and American archi Darcy Bonner Exhibition tects of the Modern Movement is the fifth in The Art Institute of Laurence Booth The Modern Movement: Selections from the Chicago's Architecture in Context series. The theme of Modern William Drake, Jr. Permanent Collection April 9 - November 20, 1988 ism became a viable exhibition topic as the Department of Archi Lonn Frye Galleries 9 and 10, The Art Institute of Chicago tecture steadily strengthened over the past five years its collection Michael Glass Lectures of drawings dating from the first four decades of this century. In Joseph Gonzales Dennis P. Doordan, Assistant Professor of Architec the case of some architects, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Bruce Gregga tural History, University of Illinois at Chicago, "The Ludwig Hilberseimer, Paul Schweikher, William Deknatel, and Marilyn and Modern Movement in Architectural Drawin gs," James Edwin Quinn, the drawings represented in this exhibition Wilbert Hasbrouck Wednesday, April 27, 1988,at 2:30 p.m. , at The Art are only a small selection culled from the large archives of their Scott Himmel Institute of Chicago. Admission by ticket only. For reservations, telephone 443-3915. drawings that have been donated to the Art Institute. In the case Helmut Jahn of European Modernists whose drawings rarely come on the mar James L. Nagle Steven Mansbach, Acting Associate Dean of the ket, such as Eric Mendelsohn, J. J. P. Oud, and Le Corbusier, the Gordon Lee Pollock Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Na Art Institute has acquired drawings on an individual basis as John Schlossman tional Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., "Reflections works by these renowned architects have become available. -

Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, Ve Aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Jonathan Vimr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Vimr, Jonathan, "Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 211. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 Suggested Citation: Vimr, Jonathan (2013). Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Abstract Just as architectural history traditionally takes the form of a march of styles, so too do preservationists repeatedly campaign to save seminal works of an architectural manner several decades after its period of prominence. This is currently happening with New Brutalism and given its age and current unpopularity will likely soon befall postmodern historicism. In hopes of preventing the loss of any of the manner’s preeminent works, this study provides professionals with a framework for evaluating the significance of postmodern historicist designs in relation to one another. Through this, the limited resources required for large-scale preservation campaigns can be correctly dedicated to the most emblematic sites. Three case studies demonstrate the application of these criteria and an extended look at recent preservation campaigns provides lessons in how to best proactively preserve unpopular sites. -

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

CAA-Final 4.18Am.Pdf

GENETIC MEMORY A memory present at birth that exists in the absence of sensory experience and is incorporated into the genome over long spans of time Rodolfo R Llinas, I of the Vortex: From Neurons to self, 2001 • Need for contact with nature • Desire to be with people • Preference for handmade products & local material • Longing for blending-in & aspiration for personalization • Being at ease in human scale of spaces A fluid landscape … NEED FOR CONTACT WITH NATURE Work Image: typical village layout (sketch) why not intimidated by the unfamiliar setting? why this affinity to nature? A person from a cold climate, who is used to be protected from nature, is instantly drawn to a tropical island where indoors cannot be separated from the outdoors “picture window” where nature is enjoyed like a picture from the protected comfort of the warm indoors Is it because for thousands of years we the human race have evolved in nature? Our intimacy with nature has been for too long a period to be ignored or disassociated. DESIRE TO BE WITH PEOPLE PREFERENCE FOR HANDMADE PRODUCTS & LOCAL MATERIALS We notice amongst people, irrespective of our geographical location, a general visual and tactile bias towards products where we can feel a human touch. Whether the product is an item of clothing; furniture; a household item we use every day or something we put in our homes to satisfy our aesthetic desires, we put more value on products that have a human behind its creation. All forms of Art are valued the most. Art, thankfully till now, cannot be factory produced. -

Prospectus 2006.1.Indd

I•N•T•B•A•U International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture & Urbanism Patron: His royal highness THE PRINCE OF WALES P ro s p e c t u s Dr Matthew Hardy • Aura Neag London • May 2006 Produced by Dr Matthew Hardy and Aura Neag for the International Network for Traditional Building Architecture & Urbanism © INTBAU 2006 all rights reserved # Contents Char ter A personal message from our Patron, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales 1. Introduction 1.1 INTBAU 1.2 Need for INTBAU 1.3 Support for INTBAU 1.4 Charter 1.5 Committee of Honour 1.6 Chapters 1.7 Patron 1.8 Income 2. Membership 2.1 General Membership 2.2 Higher Membership 2.3 INTBAU College of Traditional Practitioners ICTP 3. Activities 4. Recent projects 5. Future projects 6. How you can support INTBAU 7. Appendices 7.1 Organisational structure diagrams 7.2 Members of Board 7.3 Members of Committee of Honour 7.4 Members of Management Committee 3 Charter The International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism is an active network of individuals and institutions dedicated to the creation of humane and harmonious buildings and places that respect local traditions. • • • • • Traditions allow us to recognise the lessons of history, enrich our lives and offer our inheritance to the future. Local, regional and national traditions provide the opportunity for communities to retain their individuality with the advance of globalisation. Through tradition we can preserve our sense of identity and counteract social alienation. People must have the freedom to maintain their traditions. Traditional buildings and places maintain a balance with nature and society that has been developed over many generations. -

Bi Works for Issuu.Cdr

BENGAL INSTITUTE WORKS The Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements is a unique, multi-disciplinary forum for the study and design of the environment. As a place for advancing the understanding of the lived environment, the Bengal Institute presents a platform for developing ideas to improve the qualities of architecture, landscapes, cities and settlements in Bangladesh. In generating a critical, creative and humanistic dialogue, the Institute applies an integrated approach to the study and rearrangement of the environment. Innovative transdisciplinary programs of the Institute integrate architectural and design research, investigation of cities and settlements, and the study of larger regions and landscapes. ACADEMIC PROGRAM With the intention of creating an inter-disciplinary, postgraduate educational development in architecture, urban design, landscape design, and settlement studies in Bangladesh, Bengal Institute's Academic Program was launched in August, 2015. Structured around seminars, lecture series, and workshop styled design studios, the Academic Program offers monthly sessions in Spring and Fall Sequences that are open to anyone with an interest in the study and rearrangement of the environment. Faculty with national and international repute conducts the activities of the program. RESEARCH AND DESIGN PROGRAM The Research and Design Program is dedicated to the study, design and planning of cities, settlements and landscapes. With the aim of facilitating the planned physical future of Bangladesh along with socio-economic development, the Program operates at various scales, from the regional to the small neighborhood. The research and design focus of the program includes regional contexts, small towns, public space, public transport, high density livability, hydrological dynamics, landscape forms and settlement patterns. -

Boston Government Services Center: Lindemann-Hurley Preservation Report

BOSTON GOVERNMENT SERVICES CENTER: LINDEMANN-HURLEY PRESERVATION REPORT JANUARY 2020 Produced for the Massachusetts Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) by Bruner/Cott & Associates Henry Moss, AIA, LEED AP Lawrence Cheng, AIA, LEED AP with OverUnder: 2016 text review and Stantec January 2020 Unattributed photographs in this report are by Bruner/Cott & Associates or are in the public domain. Table of Contents 01 Introduction & Context 02 Site Description 03 History & Significance 04 Preservation Narrative 05 Recommendations 06 Development Alternatives Appendices A Massachusetts Cultural Resource Record BOS.1618 (2016) B BSGC DOCOMOMO Long Fiche Architectural Forum, Photos of New England INTRODUCTION & CONTEXT 5 BGSC LINDEMANN-HURLEY PRESERVATION REPORT | DCAMM | BRUNER/COTT & ASSOCIATES WITH STANTEC WITH ASSOCIATES & BRUNER/COTT | DCAMM | REPORT PRESERVATION LINDEMANN-HURLEY BGSC Introduction This report examines the Boston Government Services Center (BGSC), which was built between 1964 and 1970. The purpose of this report is to provide an overview of the site’s architecture, its existing uses, and the buildings’ relationships to surrounding streets. It is to help the Commonwealth’s Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) assess the significance of the historic architecture of the site as a whole and as it may vary among different buildings and their specific components. The BGSC is a major work by Paul Rudolph, one of the nation’s foremost post- World War II architects, with John Paul Carlhian of Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbot. The site’s development followed its clearance as part of the city’s Urban Renewal initiative associated with creation of Government Center. A series of prior planning studies by I. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS OCTOBER 1976 VOL. XX NO. 5 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103 • Marian C. Donnelly, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Associate Editor: Dora P. Crouch, School of Architecture RPI, Troy, New York 12181 • Assistant Editor: Richard Guy Wilson, 1318 Qxford Place, Charlottesville, Virginia22901. SAH NOTICES 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles-February 2-6. Adolf K. CONTRIBUTIONS OF BACK ISSUES OF SAH Placzek, Columbia University, is general chairman and David JOURNAL REQUESTED Gebhard, University of California, Santa Barbara, is local chairman. The Board of Directors of SAH voted at their May, 1976 Sessions will be held at the Biltmore Hotel February 3, 4 and 5. meeting to request those members who have the back (For a complete listing, please refer to the April1976 issue of the issues of the SAH Journal listed below and are willing to Newsletter.) The College Art Association of America will be part with them to donate them to the central office: Vols. meeting at the Hilton Hotel (a few blocks from the Biltmore) at I-VIII (1940-1949)- all numbers; Vol. IX (1950)-nos. 1, 2, 3; Vol. X (1951) - nos. I & 3; Vol. XI (1952)-nos. I, 2, the same time. As is customary, registration with either organiza tion entitles participants to attend either SAH or CAA sessions, 4; Vol. XII (1953) - no.-2; Vol. XIII (1954) - nos. I & 2; and a fruitful scholarly exchange is anticipated. Vol. XIV (1955)- all numbers; Vol. -

Arquitectura En La Era De La Austeridad Architecture in the Age of Austerity

La Arquitectura en la Era de la Austeridad Architecture in the Age of Austerity Mairea Libros Seminario Internacional International Seminar La Arquitectura en la Era de la Austeridad Architecture in the Age of Austerity Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid (ETSAM) 18 al 20 de Junio de 2013 Organizado, gracias a la generosidad de la Richard H. Driehaus Charitable Lead Trust, por el Premio Rafael Manzano Martos de Arquitectura Clásica y Restauración de Monumentos y la School of Architecture of the Notre Dame University, con la participación de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid y la colaboración del Centro de Investigación de Arquitectura Tradicional (CIAT) e INTBAU España Edición a cargo de Alejandro García Hermida Mairea Libros Editado por: Alejandro García Hermida Diseño: Helena García Hermida © De los textos sus autores © De esta edición, Mairea Libros 2013 Mairea Libros Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura Avenida Juan de Herrera, 4. 28040 MADRID Correo E: [email protected] Internet: www.mairea-libros.com ISBN: 978-84-941317-9-0 Depósito Legal: M-18411-2013 Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra sólo puede ser realizada con la autorización de sus titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la Ley 23/2006 de Propiedad Intelectual, y en concreto por su artículo 32, sobre “cita e ilustración de la enseñanza”. Impresión: StockCeroDayton San Romualdo, 26 28037 Madrid Impreso en España – Printed in Spain labor. A Carol Wyant, quien, a pesar to the search for more humane and effort. To all the wonderful friends from de la distancia física, siempre ha estado sustainable models for the practice of Escuela Superior de Arquitectura de cerca para dar la mejor solución a architecture, urbanism and cultural he- Madrid and Universidad Alfonso X cuantos escollos hemos hallado en el ritage preservation in its wider sense. -

Architecture

April Press 15 Final Cranial_Layout 1 3/8/15 12:58 PM Page 16 architecture A new book by Chatham and New York City architect George Ranalli Below: Ranalli’s book complete with clamshell shows award-winning examples of buildings and industrial products case in a vibrant red – whose design vocabulary has roots in a longer craft tradition in design has the gravitas of treasured bible. and architecture. Ace Frehley, of the rock group Kiss, wanted a house in the Connecticut countryside that expressed his need for a dwelling that would provide some respite from waking up to find fans pressing their In Situ noses against his windows. By Rich Kraham In a new, lavishly illustrated book entitled In Situ , architect George K-Loft in Chelsea, Ranalli, who owns a home on Hudson Avenue in Chatham, sums New York City. up his theoretical positions on architectural projects that he has Living room, din - ing room and been involved in here, in New York City, and around the world. kitchen as seen These include large urban projects, additions, renovations to from the entry to major landmark buildings, interiors, new constructions and the master bed - houses in the landscape. Ranalli explains that the title of his book room is from the Latin meaning “in place,” and he stresses that buildings become iconic, not because some “starchitect” has created a stunning form plopped down on a site, but because the building fits and “responds lovingly to the specificities of place.” Apparently, a host of architectural critics feel the same way. Former New York Times critic Paul Goldberger, in discussing a Ranalli project in Rhode Island to convert a school into condos, wrote: “For all its modernity, this project is an architectural experience worthy of Ranalli designs tables and other Newport, and it connects us again to the architectural traditions furniture to go of this unusual city.” Ada Louise Huxtable, an architectural critic along with his with the Wall Street Journal, wrote that Ranalli’s Saratoga Avenue interior designs. -

Robert Adam 2017 Laureate

Robert Adam 2017 Laureate Contents Press Release ……………………………………………………………… 2 Images …………………………………………………………………….. 4 Driehaus Prize ……………………………………………………………. 13 Ceremony Choregic Monument Past Laureates Henry Hope Reed Award …………………………………………………. 14 Medal Past Recipients Jury ……………………………………………………………………….. 15 Press Release Robert Adam named 15th Richard H. Driehaus Prize Laureate James S. Ackerman posthumously presented the Henry Hope Reed Award Robert Adam, an architect known for his scholarship as well as his practice, has been named the recipient of the 2017 Richard H. Driehaus Prize at the University of Notre Dame. Adam, the 15th Driehaus Prize laureate, will be awarded the $200,000 prize and a bronze miniature of the Choregic Monument of Lysikrates during a ceremony on March 25 (Saturday) in Chicago. In conjunction with the Driehaus Prize, the $50,000 Henry Hope Reed Award, given annually to an individual working outside the practice of architecture who has supported the cultivation of the traditional city, its architecture and art, will be presented posthumously to architectural historian James S. Ackerman. Additionally, on the occasion of the 15th anniversary of the Driehaus Prize, the jury has elected to honor the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) with a special award for contributions to the public realm. “Throughout his career, Robert Adam has engaged the critical issues of our time, challenging contemporary attitudes toward architecture and urban design. He has written extensively on the tensions between globalism and regionalism as we shape our built environment,” said Michael Lykoudis, Driehaus Prize jury chair and Francis and Kathleen Rooney Dean of Notre Dame’s School of Architecture. “Sustainability is at the foundation of his work, achieved through urbanism and architecture that is respectful of local climate, culture and building customs.” Adam received his architectural education at Westminster University and was a Rome Scholar in 1972–73.