Jazz and Signifying in Ishmael Reed's Mumbo Jumbo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheets to Lull To

Sheets to Lull To - Pratyaksh Gautam Lo-Fi? So, What’s Different? usic spawns countless genres, with new ones Most genres of music aim to grab your attention and Mpopping up by the dozens every few years. move you, or to make you move. Lo-fi established Among the genres to come to prominence in the last itself as a genre whose aim is to not draw too much few years, lo-fi stands out as one of the more “un- attention, as demonstrated by the title of the largest interesting” ones. It isn’t bizarre, avant-garde, nor is lo-fi live stream on the internet, ChilledCow’s 24x7 it dominating the top 40. It doesn’t have any artists “lo-fi hip hop radio - beats to relax/study to”. They’re who constantly make headlines for their fashion or repetitive, relaxed and laid-back beats, with rarely relationships. any comprehensible lyrics, to be played without It begs the much more “interesting” question, why needing to pay attention, as filler, think Phillip Glass is such a seemingly niche genre enjoying growing meets J Dilla. popularity? Simply put, lo-fi hip hop is this generation’s elevator Lo-fi, short for ‘low fidelity’ is a genre of music music, well suited for late-night study sesh’s, or drawing largely on hip-hop, with elements of other questionable activities best appreciated with sampling, classic old school drum machine sounds, a calm ambience. lo-fi has existed in some way or unquantised drums, slightly detuned synths, form for a long time, but has recently attracted a repetition, and repetition. -

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

Press Release

PRESS Press Contact Rachel Eggers Associate Director of Public Relations [email protected] RELEASE 206.654.3151 FEBRUARY 24, 2020 JOHN AKOMFRAH: FUTURE HISTORY OPENS AT THE SEATTLE ART MUSEUM MARCH 5, 2020 SAM’s first special exhibition dedicated to video art features three works by celebrated British artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah SEATTLE, WA – The Seattle Art Museum (SAM) presents John Akomfrah: Future History (March 5–May 3, 2020), the museum’s first special exhibition exclusively dedicated to the medium of video art. Transforming SAM’s galleries into immersive theaters, Future History brings together three video works by John Akomfrah, the pioneering contemporary British filmmaker. The three works present a provocative vision of the past, present, and future, exploring issues such as climate change, slavery, colonialism, migration, and technology. Akomfrah’s uniquely personal and poetic visual language seeks to open a dialogue, rather than impose one truth. Future History was curated by Pam McClusky, Curator of African and Oceanic Art at SAM. “This presentation challenges the notion of what an exhibition can be,” says McClusky. “Instead of seeing many artworks, you’re sitting down to experience three that have incredible depth. The title of the exhibition speaks to the artist’s aim: to present crucial moments of history from different perspectives so that not-yet-imagined futures can emerge.” The artist will travel to Seattle for the opening. “In this exhibition, you’ll explore three moments from the last 500 years of history,” says Akomfrah. “My work offers an experience that pushes against this era of small screens and isolation. -

Nna Luke Abbott : Biography

nna luke abbott : biography It was towards the end of 2010 when Norfolk's self-styled ambassador of art school electronica Luke Abbott first unveiled the lush organic textures and pagan hypnotics of 'Holkham Drones', his ever-so- slightly-wonky debut album that takes its name from a beach on Norfolk's surprisingly northern section of coast. In the intervening months that have since elapsed, the unassuming twelve track collection of handcrafted hardware-jams has won over convert upon convert, staking a claim alongside recent releases from Four Tet and Gold Panda as one of the definitive works of the UK's ever-bolder Kraut- tinged corner of the dance music spectrum, as well as making serious inroads with the Drowned In Sound indie set, for whom the “game-changing electronic opus” stood out as “far and away one of DiS' favourite records of 2010”. Luke Abbott spent his formative years in the Norfolk fenland village of North Lopham, surrounded by records lovingly hoarded by his pop music historian father Kingsley, author of biographical tomes encompassing Sixties luminaries such as The Beach Boys and Phil Spector. Luke first headed towards the bright lights of Norwich to enrol at the city's respected art school, soon followed by a course in Electroacoustic Composition at the UEA. Here the university's open-minded approach would allow him to indulge all of his technological curiosities, wandering at will down the various experimental avenues that run through electronic music's leftfield. This hands-on and homemade DIY approach has continued to inform his fledgling steps into a musical career, from circuit-bending and hardware-hacking to generating bespoke software instruments and sequencers and building his own custom MIDI controller. -

Alternative Perspectives of African American Culture and Representation in the Works of Ishmael Reed

ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of Zo\% The requirements for IMl The Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Jason Andrew Jackl San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Jason Andrew Jackl 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Alternative Perspectives o f African American Culture and Representation in the Works o f Ishmael Reed by Jason Andrew Jackl, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English Literature at San Francisco State University. Geoffrey Grec/C Ph.D. Professor of English Sarita Cannon, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED Jason Andrew JackI San Francisco, California 2018 This thesis demonstrates the ways in which Ishmael Reed proposes incisive countemarratives to the hegemonic master narratives that perpetuate degrading misportrayals of Afro American culture in the historical record and mainstream news and entertainment media of the United States. Many critics and readers have responded reductively to Reed’s work by hastily dismissing his proposals, thereby disallowing thoughtful critical engagement with Reed’s views as put forth in his fiction and non fiction writing. The study that follows asserts that Reed’s corpus deserves more thoughtful critical and public recognition than it has received thus far. To that end, I argue that a critical re-exploration of his fiction and non-fiction writing would yield profound contributions to the ongoing national dialogue on race relations in America. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

An Anthropological Exploration of the Effects of Family Cash Transfers On

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF FAMILY CASH TRANSFERS ON THE DIETS OF MOTHERS AND CHILDREN IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON Ana Carolina Barbosa de Lima Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University July, 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Eduardo S. Brondízio, PhD ________________________________ Catherine Tucker, PhD ________________________________ Darna L. Dufour, PhD ________________________________ Richard R. Wilk, PhD ________________________________ Stacey Giroux Wells, PhD Date of Defense: April 14th, 2017. ii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my research committee. I have immense gratitude and admiration for my main adviser, Eduardo Brondízio, who has been present and supportive throughout the development of this dissertation as a mentor, critic, reviewer, and friend. Richard Wilk has been a source of inspiration and encouragement since the first stages of this work, someone who never doubted my academic capacity and improvement. Darna Dufour generously received me in her lab upon my arrival from fieldwork, giving precious advice on writing, and much needed expert guidance during a long year of dietary and anthropometric data entry and analysis. Catherine Tucker was on board and excited with my research from the very beginning, and carefully reviewed the original manuscript. Stacey Giroux shared her experience in our many meetings in the IU Center for Survey Research, and provided rigorous feedback. I feel privileged to have worked with this set of brilliant and committed academics. -

Introduction: Future Texts

,QWURGXFWLRQ)XWXUH7H[WV $ORQGUD1HOVRQ 6RFLDO7H[W 9ROXPH1XPEHU 6XPPHUSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\'XNH8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by Basel, Univ of (1 Dec 2016 13:59 GMT) Introduction FUTURE TEXTS We will make our own future Text. Alondra Nelson —Ishmael Reed, Mumbo Jumbo and on to post now post new —Amiri Baraka, “Time Factor a Perfect Non-Gap” In popular mythology, the early years of the late-1990s digital boom were characterized by the rags-to-riches stories of dot-com millionaires and the promise of a placeless, raceless, bodiless near future enabled by tech- nological progress. As more pragmatic assessments of the industry sur- faced, so too did talk of the myriad inequities that were exacerbated by the information economy—most notably, the digital divide, a phrase that has been used to describe gaps in technological access that fall along lines of race, gender, region, and ability but has mostly become a code word for the tech inequities that exist between blacks and whites. Forecasts of a utopian (to some) race-free future and pronouncements of the dystopian digital divide are the predominant discourses of blackness and technology in the public sphere. What matters is less a choice between these two nar- ratives, which fall into conventional libertarian and conservative frame- works, and more what they have in common: namely, the assumption that race is a liability in the twenty-first century—is either negligible or evi- dence of negligence. In these politics of the future, supposedly novel para- digms for understanding technology smack of old racial ideologies. In each scenario, racial identity, and blackness in particular, is the anti-avatar of digital life. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

Vodou and the U.S. Counterculture

VODOU AND THE U.S. COUNTERCULTURE Christian Remse A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2013 Committee: Maisha Wester, Advisor Katerina Ruedi Ray Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Tori Ekstrand Dalton Jones © 2013 Christian Remse All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Maisha Wester, Advisor Considering the function of Vodou as subversive force against political, economic, social, and cultural injustice throughout the history of Haiti as well as the frequent transcultural exchange between the island nation and the U.S., this project applies an interpretative approach in order to examine how the contextualization of Haiti’s folk religion in the three most widespread forms of American popular culture texts – film, music, and literature – has ideologically informed the U.S. counterculture and its rebellious struggle for change between the turbulent era of the mid-1950s and the early 1970s. This particular period of the twentieth century is not only crucial to study since it presents the continuing conflict between the dominant white heteronormative society and subjugated minority cultures but, more importantly, because the Enlightenment’s libertarian ideal of individual freedom finally encouraged non-conformists of diverse backgrounds such as gender, race, and sexuality to take a collective stance against oppression. At the same time, it is important to stress that the cultural production of these popular texts emerged from and within the conditions of American culture rather than the native context of Haiti. Hence, Vodou in these American popular texts is subject to cultural appropriation, a paradigm that is broadly defined as the use of cultural practices and objects by members of another culture. -

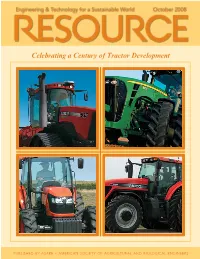

Resource Magazine October 2008 Engineering and Technology for A

Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development PUBLISHED BY ASABE – AMERICAN SOCIETY OF AGRICULTURAL AND BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERS Targeted access to 9,000 international agricultural & biological engineers Ray Goodwin (800) 369-6220, ext. 3459 BIOH0308Filler.indd 1 7/24/08 9:15:05 PM FEATURES COVER STORY 5 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development Carroll Goering Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Plowing down memory lane: a top-six list of tractor changes over the last century with emphasis on those that transformed agriculture. Vol. 15, No. 7, ISSN 1076-3333 7 Adding Value to Poultry Litter Using ASABE President Jim Dooley, Forest Concepts, LLC Transportable Pyrolysis ASABE Executive Director M. Melissa Moore Foster A. Agblevor ASABE Staff “This technology will not only solve waste disposal and water pollution Publisher Donna Hull problems, it will also convert a potential waste to high-value products such as Managing Editor Sue Mitrovich energy and fertilizer.” Consultants Listings Sandy Rutter Professional Opportunities Listings Melissa Miller ENERGY ISSUES, FOURTH IN THE SERIES ASABE Editorial Board Chair Suranjan Panigrahi, North Dakota State University 9 Renewable Energy Gains Global Momentum Secretary/Vice Chair Rafael Garcia, USDA-ARS James R. Fischer, Gale A. Buchanan, Ray Orbach, Reno L. Harnish III, Past Chair Edward Martin, University of Arizona and Puru Jena Board Members Wayne Coates, University of Arizona; WIREC 2008 brought together world leaders in the fi eld of renewable energy Jeremiah Davis, Mississippi State University; from 125 countries to address the market adoption and scale-up of renewable Donald Edwards, retired; Mark Riley, University of Arizona; Brian Steward, Iowa State University; energy technologies. -

MALAUENE Umn 0130E 22082.Pdf

A history of music and politics in Mozambique from the 1890s to the present A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY DENISE MARIA MALAUENE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUEREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ALLEN F. ISAACMAN JANUARY 2021 Ó DENISE MARIA MALAUENE, 2021 Acknowledgements Nhi bongide ku womi ni vikelo Thank you for life and protection Nhi bongide gurula ni guhodza Thank you for peace and provision Nhi bongide gu nengela omo gu Thank you for happiness in times of tsanisegani suffering Nhi bongide Pfumu Thank you, God! Denise Malauene song titled “Nhi bongide Pfumu”1 Pfumu Nungungulu, nhi bongide ngudzu! (Thank you, God!) My children Eric Silvino Tale and Malik TSakane Malauene Waete: I thank you for your unconditional love, Support, and understanding aS many timeS I could not be with you nor could meet your needs because I waS studying or writing. Mom and dad Helena ZacariaS Pedro Garrine and João Malauene, nhi bongide ku SatSavbo. My Siblings Eduardo Malauene, GiSela Malauene, Guidjima Donaldo, CriStina AgneSS Raúl, DioníSio, Edson Malauene, ChelSea Malauene, Kevin Malauene, obrigada por tudo. I am grateful to my adviSor Allen IsSacman for the advice, guidance, and encouragement, particularly during the difficult timeS in my Ph.D. trajectory Somewhat affected by Several challengeS including CycloneS Idai, the armed instability in central and northern Mozambique, and Covid 19. Barbara’s and hiS support are greatly appreciated. I am grateful to ProfeSSor Helena Pohlandt-McCormick for her encouragement, guidance, and Support. Her contribution to the completion of my degree in claSSeS, reading groups, paper preSentations, grant applications, the completion of my prelimS, and Michael’s and her support are greatly appreciated.