Broad Parties and the Fight for Left Unity in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Left Info Flyer

United for a left alternative in Europe United for a left alternative in Europe ”We refer to the values and traditions of socialism, com- munism and the labor move- ment, of feminism, the fem- inist movement and gender equality, of the environmental movement and sustainable development, of peace and international solidarity, of hu- man rights, humanism and an- tifascism, of progressive and liberal thinking, both national- ly and internationally”. Manifesto of the Party of the European Left, 2004 ABOUT THE PARTY OF THE EUROPEAN LEFT (EL) EXECUTIVE BOARD The Executive Board was elected at the 4th Congress of the Party of the European Left, which took place from 13 to 15 December 2013 in Madrid. The Executive Board consists of the President and the Vice-Presidents, the Treasurer and other Members elected by the Congress, on the basis of two persons of each member party, respecting the principle of gender balance. COUNCIL OF CHAIRPERSONS The Council of Chairpersons meets at least once a year. The members are the Presidents of all the member par- ties, the President of the EL and the Vice-Presidents. The Council of Chairpersons has, with regard to the Execu- tive Board, rights of initiative and objection on important political issues. The Council of Chairpersons adopts res- olutions and recommendations which are transmitted to the Executive Board, and it also decides on applications for EL membership. NETWORKS n Balkan Network n Trade Unionists n Culture Network Network WORKING GROUPS n Central and Eastern Europe n Africa n Youth n Agriculture n Migration n Latin America n Middle East n North America n Peace n Communication n Queer n Education n Public Services n Environment n Women Trafficking Member and Observer Parties The Party of the European Left (EL) is a political party at the Eu- ropean level that was formed in 2004. -

Janice Godrich - Why I’M Standing for Election As the Left Unity Candidate for PCS Assistant General Secretary

Janice Godrich - Why I’m standing for election as the Left Unity candidate for PCS Assistant General Secretary It has been a privilege to have been elected annually by members since 2002 as PCS President. I am standing for election as the Left Unity candidate for the post of PCS Assistant General Secretary and ask that you consider voting for me. It is the most important decision I have taken in over 35 years as a PCS activist. I am standing for election on the basis of my experience, my record of achievement and most importantly our policies set by our democratic conference for the future direction of our union. If elected I pledge to only take an average workers wage. I have vast experience as an activist. I have been a PCS rep and activist since 1981. I began like most of you as a workplace rep in what was then the Employment Service, now DWP. I was soon elected as a regional rep and then served as Group President before being elected by PCS members as our national president a record 17 consecutive times. Nobody has been elected by all PCS members as often as me. I am clearly the most electable candidate and best placed to secure this post for Left Unity. My record of achievement is second to none. I have negotiated at all levels of the union and on a wide range of issues. From my beginning as a local rep, through my leadership of the Employment Service to 17 years as President I have negotiated, campaigned and won for our members. -

Cleaning the Muck of Ages from the Windows Into the Soul of Tax

Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 5 (2016), DOI: 10.1515/bjals-2016-0006 Cleaning the Muck of Ages from the Windows Into the Soul of Tax John Passant* Australian National University, Australia ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to provide readers with an insight into Marx’s me- thods as a first step to understanding income tax more generally but with specific reference to Australia’s income tax system. I do this by introducing readers to the ideas about the totality, that is, capitalism, appearance, and form, and the dialectic in Marx’s hands. This will involve looking at income tax as part of the bigger picture of capitalism and understanding that all things are related and changes in one produce changes in all. Appearances can be deceptive, and we need to delve below the surface to understand the reali- ty or essence of income and, hence, of income tax. Dialectics is the study of change. By developing an understanding of the processes of contradiction and change in society, the totality, we can then start to understand income tax and its role in our current society more deeply. To do that, we need to understand the ways of thinking and approaches that Marx and others have used. Only then, armed with the tools that we have uncovered, we can begin the process of cleaning the muck of ages from the windows into the soul of tax and move from the world of appearance to the essence of tax. CONTENTS I. Introduction ....................................................................... 179 II. Of Icebergs and other Titanic Arguments ..................... -

A Critical and Comparative Analysis of Organisational Forms of Selected Marxist Parties, in Theory and in Practice, with Special Reference to the Last Half Century

Rahimi, M. (2009) A critical and comparative analysis of organisational forms of selected Marxist parties, in theory and in practice, with special reference to the last half century. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/688/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A critical and comparative analysis of organisational forms of selected Marxist parties, in theory and in practice, with special reference to the last half century Mohammad Rahimi, BA, MSc Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Centre for the Study of Socialist Theory and Movement Faculty of Law, Business and Social Science University of Glasgow September 2008 The diversity of the proletariat during the final two decades of the 20 th century reached a point where traditional socialist and communist parties could not represent all sections of the working class. Moreover, the development of social movements other than the working class after the 1960s further sidelined traditional parties. The anti-capitalist movements in the 1970s and 1980s were looking for new political formations. -

SYRIZA, Bloco and Podemos

Transnational networking and cooperation among neo-reformist left parties in Southern Europe during the Eurozone crisis: SYRIZA, Bloco and Podemos Vladimir Bortun The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. March 2019 Abstract European parties to the left of social democracy have always lagged behind the main political families in terms of transnational cooperation at the level of the EU. However, the markedly transnational character of the Eurozone crisis and of the management of that crisis has arguably provided a uniquely propitious context for these parties to reduce that gap. This research project aims to establish whether they achieved that by focusing on three parties that were particularly prone to seeking an increase in their transnational cooperation: SYRIZA from Greece, Bloco de Esquerda from Portugal and Podemos from Spain. For these parties not only come from the member states most affected by the crisis, both economically and politically, but they also share several programmatic and strategic features favouring such an increase. By using a mix of document analysis, semi-structured interviews and non-participatory observation, the thesis discusses both the informal and formal transnational networking and cooperation among the three parties. This discussion reveals four key findings, with potentially useful insights for wider transnational party cooperation that are to be pursued in future research. Firstly, the transnational networking and cooperation among SYRIZA, Bloco and Podemos did increase at some point during the crisis, particularly around SYRIZA’s electoral victory in January 2015. Secondly, since the U-turn of that government in July 2015, SYRIZA’s relationship with both Bloco and Podemos has declined significantly, as reflected in their diverging views of the EU. -

August 2009 / 1

SOCIALIST VOICE / AUGUST 2009 / 1 Contents 338. Left Refoundation: For new unity on an anti-sectarian basis Rowland Keshena 339. Vancouver Socialist Forum Statement of Purpose 340. Venezuela: The best defence is to deepen the Revolution Marea Socialista 341. Venezuela: Class struggle intensifies over battle for workers’ control Federico Fuentes 342. Honduras Coup: Template for a Hemispheric Assault on Democracy Felipe Stuart Cournoyer 343. Climate Justice: Red is the New Green Jeff White 344. ALBA, the English-Speaking Caribbean, and the Coup in Honduras Faiz Ahmed 345. Two Accounts of Engels’ Revolutionary Life Ian Angus 346. Afghan Women’s Rights Leader Says Foreign Troops Should Leave Interview with Malalai Joya 347. Political Crisis, Economic Crisis: Challenges for the Radical Left Alex Callinicos 348. ‘Black Book’ Exposes Canadian Imperialism Suzanne Weiss ——————————————————————————————————— Socialist Voice #338, August 4, 2009 Left Refoundation: For new unity on an anti-sectarian basis LeftViews is Socialist Voice’s forum for articles related to rebuilding the left in Canada and around the world, reflecting a wide variety of socialist opinion. This article is an excerpt from a statement by Rowland Keshena, an indigenous socialist activist in southwestern Ontario. It was published in his blog, By Any Means Necessary, which “aims to be a home for anyone who wants to change the current system of oppression and exploitation.” We encourage readers to read the full text, which includes much more on the author’s background and experiences, and an excellent 10-point program entitled “What I Stand For.” It is online here. * * * * * * By Rowland Keshena This is a (brief) statement of my background, belief and principles that I hope will help in bringing my readers closer to an understanding of what I want to see in the world and where I am SOCIALIST VOICE / AUGUST 2009 / 2 coming from. -

Although Many European Radical Left Parties

Peace, T. (2013) All I'm asking, is for a little respect: assessing the performance of Britain's most successful radical left party. Parliamentary Affairs, 66(2), pp. 405-424. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/144518/ Deposited on: 21 July 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 2 All I’m asking, is for a little Respect: assessing the performance of Britain’s most successful radical left party BY TIMOTHY PEACE1 ABSTRACT This article offers an overview of the genesis, development and decline of the Respect Party, a rare example of a radical left party which has achieved some degree of success in the UK. It analyses the party’s electoral fortunes and the reasons for its inability to expand on its early breakthroughs in East London and Birmingham. Respect received much of its support from Muslim voters, although the mere presence of Muslims in a given area was not enough for Respect candidates to get elected. Indeed, despite criticism of the party for courting only Muslims, it did not aim to draw its support from these voters alone. Moreover, its reliance on young people and investment in local campaigning on specific political issues was often in opposition to the traditional ethnic politics which have characterised the electoral process in some areas. When the British public awoke on the morning of Friday 6th May 2005 most would have been unsurprised to discover that the Labour Party had clung on to power but with a reduced majority, as had been widely predicted. -

LSE Brexit: Lexit Undermines the Left – It Will Be No Prize for Labour Page 1 of 3

LSE Brexit: Lexit undermines the Left – it will be no prize for Labour Page 1 of 3 Lexit undermines the Left – it will be no prize for Labour Brexit has been very divisive for the Left in Britain. While some socialist intellectuals claim that it is a prize within reach for the Labour movement, it remains largely a neo-colonial project of a ‘Global Britain’, writes Peter J. Verovšek. He argues that the case for Lexit ignores the right-wing roots of the EU referendum, and that it will be no prize for Labour. Much like support for Europe, Euroscepticism cuts across the political spectrum rather than through it. The rifts within the Conservative Party – whose members have to take decisions while in government – are obvious. However, Brexit is equally divisive for the Labour Party. While some took to the streets of Liverpool outside the party’s conference calling for a ‘people’s vote’ to stop Brexit, Jeremy Corbyn has remained conspicuously silent. In contrast to the reticence of the Labour leadership, some socialist intellectuals have claimed – and continue to claim – that ‘Brexit is a prize within reach for the British left’. The ‘left case for Brexit’ is based on the idea that it reempowers the democratic state, which these thinkers argue the left has historically been able to use to further its agenda. Noting the importance of nationalisation – which is prohibited under EU laws against state aid – as a tool of the left, the principled argument for Lexit notes that a new socialist agenda can only be achieved once the UK is free from the quasi-constitutional constraints of the EU. -

Socialist Fight No.23

Page Socialist Fight Liaison Committee for the Fourth International No. 23 Autumn 2016 Price: Cons: £1, Waged: £2.00 (€2) Major setbacks for Anglo-American imperialism: Corbyn humiliates the Blairites and the US- sponsored coup fails in Turkey Leon Trotsky: I am confident of the victory of the Fourth International; Go Forward! Page 2 Socialist Fight Where We Stand (extracts) Socialist Fight is a member of the Liaison 1. We stand with Karl Marx: ‘The emancipa- ist state to ban fascist marches or parties; these Committee for the Fourth International tion of the working classes must be conquered laws would inevitably primarily be used against with: by the working classes themselves. The strug- workers’ organisations, as history has shown. The Communist Workers Front, Brazil gle for the emancipation of the working class 14. We oppose all immigration controls. Inter- The Socialist Workers League, USA and means not a struggle for class privileges and national finance capital roams the planet in Tendencia Militante Bolchevique, Argentina monopolies but for equal rights and duties and search of profit and imperialist governments The Editorial Board is: the abolition of all class rule’ (The Internation- disrupts the lives of workers and cause the Gerry Downing, Ian Donovan, Carl al Workingmen’s Association 1864, General collapse of whole nations with their direct Zacharia, Ailish Dease, Chris Williams, Rules). The working class ‘cannot emancipate intervention in the Balkans, Iraq and Afghani- and Clara Rosen. itself without emancipating itself from all other stan and their proxy wars in Somalia and the Contact: Socialist Fight PO Box 59188, sphere of society and thereby emancipating all Democratic Republic of the Congo, etc. -

Scottish Leftreview

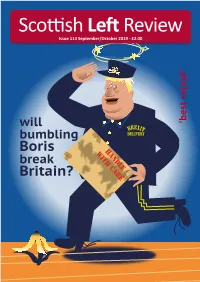

ScottishLeft Review Issue 113 September/October 2019 - £2.00 'best re(a)d' 'best 1 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 113 September/October 2019 ASLEF CALLS FOR AN INTEGRATED, PUBLICLY OWNED, ACCOUNTABLE RAILWAY FOR SCOTLAND (which used to be the SNP’s position – before they became the government!) Mick Whelan Tosh McDonald Kevin Lindsay General Secretary President Scottish Ocer ASLEF the train drivers union- www.aslef.org.uk STUC 2018_Layout 1 09/01/2019 10:04 Page 1 Britain’s specialist transport union Campaigning for workers in the rail, maritime, offshore/energy, bus and road freight sectors NATIONALISE SCOTRAIL www.rmt.org.uk 2 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 113 September/OctoberGeneral 2019Secretary: Mick Cash President: Michelle Rodgers feedback comment Like many others, Scottish Left Review is outraged at the attack on democracy represented by prorogation and condemns this extended suspension of Parliament to allow for a no-deal Brexit to be forced through without any parliamentary scrutiny or the opportunity for parliamentary opposition. Scottish Left Review supports initiatives to mobilise citizens outside of Parliament to confront this anti-democratic outrage. We call on all opposition MPs and Tory MPs who believe in parliamentary democracy to join together to defeat this outrage. All the articles in this issue (bar Kick up the Tabloids) were written before reviewsthe prorogation on 28 August 2019. t has long been a shibboleth on the Who will benefit from Brexit? of contradictions. This is certainly true radical left, following from Marx and as Boris seems to be prepared to engage In the lead article in this issue, George Engels, that politics in the last instance in Keynesian-style reflation to try to aid I Kerevan explains this perplexing situation bends to the will of economics. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

Summary of Results

Summary of Results Printed: 14 May 2015 Election: Electoral Ward held on 07/05/2015 Ward: Bowthorpe Electorate: 8811 Sands, Mike Labour Party 1955 39.98 % (Elected) Seats: 1 Elmer, Daniel Edward Conservative Party 1087 22.23 % Votes Cast: 4913 Turnout % 55.76 % Masters, Eric Phillip Ashwell UK Independence Party 743 15.19 % (UKIP) Bishop, Jean Kathleen Green Party 710 14.52 % Johnston, Thomas Jack Liberal Democrats 395 8.08 % Labour Party hold Majority: 868 ELECSUMM - Summary of Results Page: 1 Report Version Date: 31/07/2013-1 Summary of Results Printed: 14 May 2015 Election: Electoral Ward held on 07/05/2015 Ward: Catton Grove Electorate: 8245 Kendrick, Paul Labour Party 1702 36.49 % (Elected) Seats: 1 Holmes, Will Conservative Party 1411 30.25 % Votes Cast: 4690 Turnout % 56.88 % Ho, Michelle UK Independence Party 799 17.13 % (UKIP) Park, Tony Arthur Green Party 483 10.36 % Tooke, Leigh Liberal Democrats 269 5.77 % Labour Party hold Majority: 291 ELECSUMM - Summary of Results Page: 2 Report Version Date: 31/07/2013-1 Summary of Results Printed: 14 May 2015 Election: Electoral Ward held on 07/05/2015 Ward: Crome Electorate: 7334 Waters, Alan Henry Labour Party 1821 42.27 % (Elected) Seats: 1 Mackie, David John Conservative Party 1132 26.28 % Votes Cast: 4325 Turnout % 58.97 % Williams, Ann Doris UK Independence Party 793 18.41 % (UKIP) Ford, Judith Marianne Green Party 350 8.12 % Thomas, Chris Liberal Democrats 175 4.06 % Sweeney, Anthony Left Unity 37 0.86 % Labour Party hold Majority: 689 ELECSUMM - Summary of Results Page: 3 Report