Rethinking Mental Illness with Pen in Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(2016) When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi

When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Random House Publishing Group (2016) http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Copyright © 2016 by Corcovado, Inc. Foreword copyright © 2016 by Abraham Verghese All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. RANDOM HOUSE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kalanithi, Paul, author. Title: When breath becomes air / Paul Kalanithi ; foreword by Abraham Verghese. Description: New York : Random House, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2015023815 | ISBN 9780812988406 (hardback) | ISBN 9780812988413 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Kalanithi, Paul—Health. | Lungs—Cancer—Patients—United States—Biography. | Neurosurgeons—Biography. | Husband and wife. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | MEDICAL / General. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Death & Dying. Classification: LCC RC280.L8 K35 2016 | DDC 616.99/424—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015023815 eBook ISBN 9780812988413 randomhousebooks.com Book design by Liz Cosgrove, adapted for eBook Cover design: Rachel Ake v4.1 ep http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Editor's Note Epigraph Foreword by Abraham Verghese Prologue Part I: In Perfect Health I Begin Part II: Cease Not till Death Epilogue by Lucy Kalanithi Dedication Acknowledgments About the Author http://ikindlebooks.com When Breath Becomes Air Paul Kalanithi EVENTS DESCRIBED ARE BASED on Dr. Kalanithi’s memory of real-world situations. However, the names of all patients discussed in this book—if given at all—have been changed. -

The Literary Neurosurgeon

IS THE OFFICIAL NEWSMAGAZINE OF THE CONGRESS OF NEUROLOGICAL SURGEONS SPRING 2016 < 8 > STORIES FROM A Telling Stories: WAR ZONE < 30 > The Literary THE INTERNATIONAL DIVISION: STRONG AND GROWING Neurosurgeon Spring 2016 EDITOR’S NOTE Volume 17, Number 2 EDITOR: Gerald A. Grant, MD, FACS CO-EDITOR: It is my sincere pleasure to introduce the spring issue of Michael Y. Wang, MD, FACS Congress Quarterly (cnsq). In this issue, we will dive into EDITORIAL BOARD: the minds of neurosurgeons around the globe who also have Aviva Abosch, MD become prolific writers. What motivates them to tell their Kimon Bekelis Edward C. Benzel, MD stories? Who inspired them to write and how has this writing Nicholas M. Boulis, MD shaped their careers as neurosurgeons? How do they achieve James S. Harrop, MD balance in their lives? We interviewed seven accomplished Todd Charles Hollon, MD neurosurgeons to better understand what motivates them to Vivek Mehta, MD Charles J. Prestigiacomo, MD write. Brian T. Ragel, MD Jason M. Schwalb, MD Gerald A. Grant, MD We first hear from Dr. Henry Marsh, who is a consultant Ashwini Dayal Sharan, MD neurosurgeon in the United Kingdom and recently published Kyle Anthony Smith Jamie S. Ullman, MD, FACS his book Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain MANAGING EDITOR: Surgery. This is a frank and powerful narrative of his life in neurosurgery. Mr. Marsh Antonia D. Callas admits that “as a writer, you’re trying to describe things because you’re involved, STAFF EDITORS: but you remain detached and struggle to write objectively.” I had the opportunity of Michele L. -

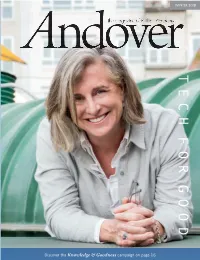

T E C H F O R G O

WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER WINTER 2 018 Periodicals postage paid at 2 018 Andover, MA and additional mailing oces Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachuses 01810-4161 Households that receive more than one Andover magazine are encouraged to call 978-749-4267 to discontinue extra copies. TECH PHILLIPS ACADEMY SUMMER SESSION July 3–August 5, 2018 F OR G Introduce your child to a whole new world OOD of academic and cultural enrichment this summer. Learn more at www.andover.edu/summer Discover the Knowledge & Goodness campaign on page 16 WINTER 2 018 -

Alumni Journal, School of Medicine Loma Linda University Publications

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Alumni Journal, School of Medicine Loma Linda University Publications 4-2017 Alumni Journal - Volume 88, Number 1 Loma Linda University School of Medicine Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/sm-alumni-journal Part of the Other Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Loma Linda University School of Medicine, "Alumni Journal - Volume 88, Number 1" (2017). Alumni Journal, School of Medicine. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/sm-alumni-journal/24 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Loma Linda University Publications at TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Journal, School of Medicine by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alumni JOURNALAlumni Association, School of Medicine of Loma Linda University January–April 2017 Am I My Brother’s Keeper? Reflections on physician-assisted death Coming Up APC: MarchPreview Inside 3-6 INSIDE: 85 Years of the AJ • Interview with Dr. Walter Johnson • Review: ‘When Breath Becomes Air’ TABLE of CONTENTS Alumni JOURNAL RESERVE YOUR SPOT TODAY! January–April 2017 85TH ANNUAL Volume 88, Number 1 Plenary Sessions $300 (1 day)/$600 (3 days) Orthopaedics Symposium $300 POSTGRADUATE Otolaryngology Symposium $300 Plastic Surgery Symposium $300 Editor Surgery Symposium $180 Burton A. Briggs ’66 CONVENTION Annual dues-paying members receive 20% off Silver perpetual members receive 40% off Associate Editor MARCH 3-6, 2017 | LOMA LINDA, CA Gold or higher perpetual members attend free Donna L. -

Fall 2015 Young Neurosurgeonsnews Committee Editor: Edjah Nduom, MD

Young Neurosurgeons Fall 2015 Young NeurosurgeonsNEWS Committee Editor: Edjah Nduom, MD Chairman’s Message Honoring our Past; to improve the reach of the AANS and further Preparing for our our mission. Our past members are role models In This Issue… Future. for us all, and we thank them for paving this road for us. The aptly-selected theme For the past two years, the YNC was tasked for this edition of the with developing and implementing medical 2 Young Neurosurgeons student chapters at universities with neurosurgical Book Reviews Committee (YNC) residency programs. Thirty-four chapters have 3 newsletter truly embodies already been created with several more pending. Secretary’s Message the concept and mission We will be collecting annual reports from these of the YNC. In 2000, YNC members held just chapters to develop additional resources, allowing 4 under 20 liaison positions, interfacing with us to evaluate the success of the chapters over Career Column various levels of AANS leadership. Now, in 2015, time. Our hope is to evolve this process to 5 we hold over 40. Comprised of residents-in- continue to attract the best and brightest into An Interview with Ian McCutcheon training as well as young faculty at the beginning the field. We have created opportunities to of our careers, we aim to combine our clinical attract medical students to YNC leadership and 6 roles with leadership in organized neurosurgery committee roles and will continue to do so to YNC Division Reports at all facets. Through the years, have sought carry on the mission of the YNC. -

Reviews and Reflections David A

Reviews and reflections David A. Bennahum, MD, and Jack Coulehan, MD, Book Review Editors Paul Kalanithi, MD, resident in Neurological Surgery, at Stanford Hospital and Clinics, February 5, 2014. Courtesy Norbert von der Groeben/Stanford Hospital and Clinics When Breath Becomes Air Medical Center, he begins with his discovery of his immi- nent mortality. Paul Kalanithi, MD (AΩA, Yale University School of Medicine, 2007) I flipped through the CT scan images, the diagnosis Forward by Abraham Verghese, MD (AΩA, James H. Quillen College of Medicine of East Tennessee State obvious: the lungs were matted with innumerable tumors, University, 1989, Faculty) the spine deformed, a full lobe of the liver obliterated. Cancer widely disseminated. I was a neurosurgical resi- Epilogue by Lucy Kalanithi, MD (AΩA, Yale University School of Medicine, 2007) dent entering my final year of training. Over the last six Random House, New York, 2016, 228 pages years, I’d examined scores of such scans, on the off chance that some procedure might benefit the patient. But this Reviewed by David A. Bennahum, MD (AΩA, University scan was different: it was my own.p3 of New Mexico, 1984, Faculty) Growing up in Kingman, Arizona, a way station for those driving west on U.S. Route 40 to Nevada and California, a he author, Paul Kalanithi, MD, wrote an extraordinary city that his East Indian-born parents—his father Christian memoir of his life prior to his death of lung cancer and his mother Hindu—selected so that his father could atT the age of 35 in 2015. This is a beautiful, difficult, and practice cardiology where he would be truly needed, at times painful, book that can bring the reader to tears, Kalanithi and his brothers had a very western American especially if that reader is a physician. -

My Last Day As a Surgeon - the New Yorker

My Last Day as a Surgeon - The New Yorker PAGE-TURNER JANUARY 11, 2016 My Last Day as a Surgeon BY PAUL KALANITHI In May of 2013, the Stanford University neurosurgical resident Paul Kalanithi was diagnosed with Stage IV metastatic lung cancer. He was thirty-six years old. In his two remaining years—he died in March of 2015—he continued his medical training, became the father to a baby girl, and wrote beautifully about his experience facing mortality as a doctor and a patient. In this excerpt from his posthumously published memoir, “When Breath Becomes Air,” which is out on PHOTOGRAPH BY NORBERT VON DER GROEBEN January 12th, from Random House, Kalanithi writes about his last day practicing medicine. http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/my-last-day-as-a-surgeon[1/14/2016 6:38:55 PM] My Last Day as a Surgeon - The New Yorker hopped out of the CT scanner, seven months since I had returned to surgery. This would be my last scan before fnishing residency, before becoming a I father, before my future became real. “Wanna take a look, Doc?” the tech ADVERTISEMENT said. “Not right now,” I said. “I’ve got a lot of work to do today.” It was already 6 P.M. I had to go see patients, organize tomorrow’s O.R. schedule, review flms, dictate my clinic notes, check on my post-ops, and so on. Around 8 P.M., I sat down in the neurosurgery offce, next to a radiology viewing station. I turned it on, looked at my patients’ scans for the next day—two simple spine cases—and, fnally, typed in my own name. -

The Life and Death of Paul Kalanithi: the Dilemma of Illness Identity in a Physician-Turned-Patient

The Life and Death of Paul Kalanithi: The Dilemma of Illness Identity in a Physician-Turned-Patient by Daniella Conley Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2018 © Copyright by Daniella Conley, 2018 “Even if I’m dying, until I actually die, I am still living.” Paul Kalanithi ii Table of Contents Abstract...............................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements..............................................................................................................v Chapter One: Introduction....................................................................................................1 Chapter Two: Illness, Self, and Identity...............................................................................7 Chapter Three: The Role of Suffering................................................................................20 Chapter Four: Discussion...................................................................................................37 Works Cited........................................................................................................................44 iii Abstract After his diagnosis of stage IV lung cancer, Paul Kalanithi composed the memoir When Breath Becomes Air. Kalanithi’s background as a student of literature allows for a well-crafted illness narrative in which he examines his life’s journey and his experience -

Optimistic Life Reflected in Paul Kalanithi's When

OPTIMISTIC LIFE REFLECTED IN PAUL KALANITHI’S WHEN BREATH BECOMES AIR (2016) BY USING EXISTENTIALIST PERSPECTIVE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department By: FAHMI GHIFFARI A320140191 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH EDUCATION SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITAS MUHAMMADIYAH SURAKARTA 2020 APPROVAL OPTIMISTIC LIFE REFLECTED IN PAUL KALANITHI’S WHEN BREATH BECOMES AIR (2016) BY USING EXISTENTIALIST PERSPECTIVE. PUBLICATION ARTICLE By: FAHMI GHIFFARI A320140191 Approved to be examined by Consultant School of Teacher Training and Education Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta Consultant, Dr. Phil. Dewi Candraningrum, S.Pd.,M.Pd NIDN. 0609127502 i OPTIMISTIC LIFE REFLECTED IN PAUL KALANITHI’S WHEN BREATH BECOMES AIR (2016) BY USING EXISTENTIALIST PERSPECTIVE. PUBLICATION ARTICLE Written by: Fahmi Ghiffari A320140191 Accepted by: The Board by Examiners of School Teacher Training and Education Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta The Board of Examiners: 1. Dr.Phil. Dewi Candraningrum, S.Pd.,M.Pd. (………………………..) (Chair Person) 2. Dr. Muhammad Thoyibi, M.S. (Member I) (………………………..) 3. Dr. Abdillah Nugroho, M.Hum. (Member II) (………………………..) Surakarta, January 13 2020 Universitas Muhammdiyah Surakarta School of Teacher Training and Education Dean, Prof. Dr. Harun Joko Prayitno, M.Hum NIP. 19650428 199303 1 001 ii TESTIMONY Here with, I testify that in this publication article, there is no plagiarism of the previous literary work, which has been raised to obtain bachelor degree in any university, nor there are opinions or master pieces which have been written or published by others except those in which the writing are referred in this paper and mentioned in the literary review and bibliography.