University of Kentucky Lexington, KY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Irish Schools Xi V Cork Co at the Mardyke, Cork

Players quality at the right price , > .., s• ' z , 00...'" :0'" "z :> mild. smooth. satisfying PNSE 165 PACKETS CARRY A GOVERNMENT HEALTH WARNING Irish THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE IRISH CRICKET SOCIETY Television Contents and Thoughts on looking into Morgan Dockrell 3 "Strange rs' Gallery" Mix ed Season for Galway Cricketers 5 Ulster League Championship 1974 Cor{ A"derson 7 Players No.6 Cup Championships 1974 M. N.A. Bre"na" 8 CRICKET Woolm3rk/ Peter Tait Trophy M.P. Ruddle 9 The Council of Cricket Societies LC Horron 10 1974 in the North-West O. W. Todd II The Irish Schools V TIle Welsh Schools Frank Morrisson ]J The Northern Senior Cup Carl Alldersoll 14 Since its inception the Irish Television Cork County Cricket Cub 100 Not Out D.II. Donovall IS Service (RTE) has done nothing for The Guinness Cup 1974 Seal! Pellder 17 cricket eithcrnationally or internationally. Alfie Well done Skipper IS Over :I number of years many requests Guinness Cup Statistics 1974 19 have been made for the inclusion of Personalities 2()"2 1 cricket in the sports programmes, but Old We11ingtonian Irish Tour.August 1974 23 with little success. nlere is no live- Answers to the Competition in Summer 24 coverage of Irish cri cket except when lssue of "Irish Cricket" Australia or West Indies have played in As One Englishman Sees It James D. Coldham 25 Dublin, and then considerable pressure had to be applied to get some limited 'Tween Innings Teasers 26 coverage. This must now change. During The New Wiggins Tea pe League Scorer 27 1975 the World Cup Cricket Competition Mullingar c.c. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1913-05-14

THE ·DAILY. PUBLIBBED BY THE STUDENTS OF THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA VOLUMZ XU IOWA ITY, IOWA, WED IEsn,\Y MOR.'l.'O, MAY 14, 1913 T-IELLENIC SOCIETY PRfSIOENT LOWELL AND TO HOLD MEETING ASSISTANT SECRETARY BAcA~~J~~~I~ERTiPLOT OF GREEK PlAY WIFf NOW IN CITY Teachel'S of GI'Cck TIlI'oughout the FOR Y. M. C. A. CHOSfN Fit· t Open •• \lr , lu~J ftl F.\ nl .,t III HIGHLY INTfRfSTING State to Aniv in City 111 Tillie Year to H If hI Thur!odlt ' ARE Gl:ESTS OF PRESlD}JNT AND for Greek Play GRE. O'l'IERRI<;L 01.< I'EXX 0[,. E\' nlng 'It" 1('.\1, ~l"lIn; 1t IS (.1\'''; ' BY l\ffi JOliN G. nOW~IAN- J,EGE TO AID WU LL\~LS IN CROlU', nl'. \\,};E. REOEPTIO GlVl';N The annual m tlng of the Iowa TIIB WOIU\: NE:\r YE,Ut Th first op n-alr mU81c v nt RUlli.\{ ---. State Hell nlc Society of th 8 1l80n will tak pi c on the Lowell to .<lddress Students ThJs at Iowa City, l\Iay 16 and 17. The e 1'(' sldent t the Y. ~I. C.. \ , lit liberal art8 campus tomorrow v n- ('a t Con .. l~t 'h... tl MOl'ning in Natul'tIl Science AI1<U. dates wel'e arranged so that the vls Penu CoUegt' IIIHI prominent .Hh· Ing at 7: 15. 'hen th unh('rsily tOl'hUll-Is Noted AlltllOI·Jty 011 I te--WIlJ ollie to nlver,'lty Itors could attend the performance band will give & <'on rt of eight Education-Hec I>Oon I~ns t Night It ~ h'e<J on In .\1l-S ' no'll. -

The Penguin Book of Zen Poetry Received the Islands and Continents Translation Award and the Society of Midland Authors Poetry Award

INTERLUDE BOOKS 3 : PENGUIN POETS The Penguin Book ofZen Poetry Lucien Stryk's most recent of eight books of verse are Selected Poems (1976), The Duckpond (1978) and Zen Poems (1980). His Encounter with Zen: Writings on Poetry and Zen is forthcoming, as is a recording of Zen poems (original poems and translations) from Folkways Records. He has received awards for poetry, held a National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowship and a National Translation Center Grant, along with Takashi Ikemoto, to work on Zen poetry. He is editor of World of the Buddha and the anthologies Heartland: Poets of the Midwest (I and II), and translator, with Takashi Ikemoto, of, among other volumes, Afterimages: Zen Poems of Shinkichi Takahashi and Zen Poems of China and Japan The Crane's Bill. In 1978 The Penguin Book of Zen Poetry received the Islands and Continents Translation Award and the Society of Midland Authors Poetry Award. He has given poetry readings and lectured throughout the United States and England and held a Fulbright Lectureship in Iran and a Fulbright Travel/ Research grant and two visiting lectureships in Japan. He teaches Oriental literature and poetry at Northern Illinois University. Takashi Ikemoto, educated in English Literature at Kyushu Univer- sity, was Emeritus Professor of Yamaguchi University and taught English literature at Otemongakuin University in Ibaraki City. He was a Zen follower of long standing and co-translator into Japan- ese of a volume of Thomas Merton's essays on Zen and Enomiya- Lasalle's Zen: Weg iur Erleuchtung. His major concern was for many years the introduction of Zen literature to the West, and he collaborated with Lucien Stryk on a number of Zen works. -

Winter Warmer

FarleyTHE T-shirts still available Fox Election Day Megabits In search AGM – of RAM of sauce 3 th 5 6 December 6 The season’s stats The Worcester tour WINTER WARMER It probably sums up our topsy-turvy 2010 that the end-of-year Fox is released from the traps just after an October heatwave – with the weather far better than it was throughout the last month of the season. Unfortunately, the damp potential and Butch emerged August put paid to any hopes as a quality strike bowler, while of a strong end to the season, Wakeo and Geoff both had as the First team’s form good seasons. Others know OX OFF! deserted them and the Seconds that they didn’t consistently were on the wrong end of some play to their ability, and will be As many of you will already know, bizarre results. The tour, dinner looking to rectify that next year. the honourable Lord Oxley is and end of season curry night leaving Farley CC. He’s moving to all did their bit to lift spirits For the 2s, it’s been a difficult Norfolk to advise farmers on loans and ensure that come February, year with an ever-changing for their tractors and how to best we’ll all be itching to get back lineup. The big positives were invest their dubious EU grants. out there. the emergence of Shahab and Oxo has been a club stalwart for Luke, and Gary Waller was a several years, captaining the 2s There’s no doubt that, for the welcome addition to the and the Sunday side and coaching 1st team, 2010 will feel like an ranks. -

Virginia Tech Vs Clemson (9/13/1986)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1986 Virginia Tech vs Clemson (9/13/1986) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Virginia Tech vs Clemson (9/13/1986)" (1986). Football Programs. 181. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/181 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. — None Can Compete Batson is the exclusive U.S. agent for textile equipment from the leading textile manufacturers worldwide. Experienced people back up our sales with complete service, spare parts, technical assistance, training and follow-up. DREF 3 Friction Spinning Machine Excellent for Core Yarns and Multi-Component Yarns. Count range 3.5c.c. to 18c. c. Delivery speeds to 330 yds/min. Dornier Rapier Weaving Machine—Versatile enough to weave any fabric. Also ideally suited for short runs. State-of-the-art monitoring and control. An optimum tool for the creative weaver. -

Andrew Sullivan, Blogger

Endangered Species • Comics Czar • Metabolic Scientists may-june 2011 • $4.95 The New Media Andrew Sullivan, Blogger Seeking 29 great leaders... motivated to tackle big challenges facing communities around the world with a successful track record of 20-25 years of accomplishments in their primary career recognizing the value of re-engaging with Harvard to prepare for their next phase of life’s work The Advanced Leadership Fellowship is a flexible year of education, transition, and student mentoring...for great leaders from any profession who are ready to shift focus from their main income-earning years to their next years of service...guided by a unique collaboration of award-winning Harvard faculty from across professional schools. Inquire now for January 2012. Visit us online to be inspired by the possibilities: www.advancedleadership.harvard.edu Harvard University Advanced Leadership Initiative Email our Relationship Director: [email protected] . MAY-JUNE 2011 VOLUME 113, NUMBER 5 FEATURES 27 Fathoming Metabolism INCOLN A new way of studying humanity’s inner chemistry promises deep insights into L OSE health and disease R page 45 by Jonathan Shaw 32 Vita: Leverett Gleason DEPARTMENTS Brief life of a comics impresario: 1898-1971 4 Cambridge 02138 by Brett Dakin Communications from our readers 9 Right Now 34 World’s Best Blogger? Safe crossings for four-footed Andrew Sullivan, fiscal conservative friends, the power of proximity, NSTITUTION and social liberal, navigates I modern malaise IC K APH A the changing media landscape 8A -

Annual Report 2018–19

Ormond Cricket Club Incorporated Incorporation No. A00186342 ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 AFFILIATIONS Victorian Sub-District Cricket Association South East Cricket Association To be presented to the Members at the Annual General Meeting at the Bentleigh Club on Wednesday 31 July, 2019 Annual Report 2018—2019 Ormond Cricket Club NOTICE The Seventy-Second Annual General Meeting of the Ormond Cricket Club Inc. will be held at The Bentleigh Club on Wednesday 31st July 2019, commencing at 6.30 p.m. Nominations for the election of the Office Bearers must be forwarded to the Secretary by 5pm on the 24th July 2019, duly signed by the Proposer and Seconder and endorsed by the Nominee. BUSINESS 1. Confirmation of the Minutes of the previous Annual General Meeting held on 23rd July 2018. 2. Presentation of the Annual Report. 3. Adoption of the Statement of Income and Expenditure. 4. Election of Office Bearers. 5. General Business. Page 2 Annual Report 2018—2019 Ormond Cricket Club LIFE MEMBERS • E.E. Gunn † • G.V. Corbett † • H. Ladson † • W. Park † • W. Dynon † • W.A.L. Rowse † • L. Sykes † • E.J. Barwick † • G. Macpherson † • Mrs. I. Rowse † • L.G. Laver † • K. Donald † • J.L. Robertson † • R.J. Zimmer † • G. Lees • R.W. Chapman † • C.P. Hyland • D.L. Chisholm • J.G. Craig • L.M. Patterson • E.J. Plant † • A.W. Doble • C.A. Rogers † • K. Saddington † • I.W. Shields • M.V. Carracher • Mrs. B. Craig † • J. Craig (Snr) † • R. Sommerville • Mrs. L.J. Patterson • P.J.E. Scott † • G. Cowen • R. Oaten • M. Williams • G Wilcox • I Hewett • R Simon • K Greenway • M Pedersen • S Ambler † • A Gough • P Parton • T Forrest • G Zimmer • M. -

North Carolina Vs Clemson (11/5/1988)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1988 North Carolina vs Clemson (11/5/1988) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "North Carolina vs Clemson (11/5/1988)" (1988). Football Programs. 198. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/198 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRANGE YOU WORTHY OF THE BEST? is the exclusive U.S. agent for textile Batson ~ equipment from the leading textile manufacturers P r>. 'V % worldwide. Experienced people back up our sales with complete service, spare parts, technical assistance, training and follow-up. /J • KNOTEX WARP TYING MACHINE has speeds up to 600 knots per minute. HACOBA WARPERS/BEAMERS guarantee high quality warps. Yarn & Fabrics Machinery Borne Office: GrOUp, InC. BARCO INDUSTRIES, SYCOTEX: A complete integrated BOX 3978 • GREENVILLE, S.C. 29608 U.S.A. production management system for the textile industry. -

Irishcricketautumn1973.Pdf

A MESSAGE FROM OUR PATRON On behalf of all those associated with cricket in Ireland, I am delighted to welcome this magazi ne as the official Journal of The Ir is h Cricket Society_ Our appreciation of the work and enthusiasm of the many who have brought this first issue to frui tion is deep and sincere. We thank the publi shers and congratu late them on their confidence in this valuable publication. Equally we we lcome the foresight of its advertisers who recognise that cricket lovers hasten to respond to the sincerity of these sponsors of the great game. Elsewhere appear acknowledg ments to those who have aided the creat ion of this publication but I am su re that every reader with me, will wish to recognise the ge nerosity of the many contribu tors for their gifls of the high quality text and illustrations. I take this opportunity to welcome contributions from the va rious cricket unions. Our Society co-operates with cricket in Ireland at all levels. Perhaps, one day, this magazine will reveal the record in more detail, meanwhile, we are happy that a new fo rm of communication is available to reinforce our collaboration. 'Irish Cricket ', then, is not only the official journal of the Society, it is a medi um of commun ication wi th a tremendous potential to unite members of the Society and the untiring campaigners for the health of cri cket in Ireland. The Committee of The Irish Cricket SocielY are confident in the future of this splendid magazine, they are sure thal its vigour will be reflected throughout the spectrum of Irish cricket and they assure its editorial panel of their continuing and enthusiastic support. -

Engineering the Atmosphere?

Master Woodcarver • Commencement • The Euro Crisis July-August 2013 • $4.95 Engineering the Atmosphere? Responding to climate change 70792 ThereThere is a pursuitpursuit wwee allall share.share. A betterbete ter lifelifee forfor youryour fafamily,mily, a bebettertter oopportunityppporo tunityt for yyourour bubusiness,usis ness, a betterbetter legalegacycy ttoo leleaveave ththee woworld.orld. FForor ooverver 75 yyears,eaarsr , throughthrouggh warwaw r andand crisis,crisis, we hhaveave nevernen ver stoppedsts opped helpinghelpping ourour clientscliei ntn s susucceedcceed - aandnd succeedsucceedd tthehe rrightight wway.ay. StStrivingriivingn to bringbringn insinsightight ttoo everyevery investment,investment, intelligenceintelligence toto eveveryery tradetradde andand integrityintegrity to everyevery plan.plan. BecauseBece ause aass lolongng as we sstaytay trtrueue to ththeseese prprinciples,inciples, ththehe prpromiseommisi e of cacapitalismpitalism wwillill alalwayswaw ysy pprosper.rosper. We aarere MMorganorgan StStanley.anley.y AnAAndnd wewe’re’re readyready to wworkoro k foforr yoyou.u. morganstanley.com/wealthmorganstanley.y coc m/wealth © 2013 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC660528 06/13 130719_MorganStanley.indd29310075_Anthem_16.25x10.5_Rev.2_1.indd 1 5/30/13 1:56 PM Cyan Magenta Yellow Black 70792 ThereThere is a pursuitpursuit wwee allall share.share. A betterbete ter lifelifee forfor youryour fafamily,mily, a bebettertter oopportunityppporo tunityt for yyourour bubusiness,usis ness, a betterbetter legalegacycy -

Chadron State College, I Am Overwhelmed by the Many Supportive and Congratulatory Messages My Family and I Received

AlumniCHADRON STATE MagazineSummer 2013 Table of contents The Big Event is a smashing success . 1 Campus celebrates Rhine inauguration . 2 Graduatation . 10 Ivy Day . 11 CSC Sports . 14 Living Legacy Society . 17 Class Notes . 20 Letter from the President Dear Alumni, As I reflect back on my April 26 inauguration by the Nebraska State College System as the 11th president of Chadron State College, I am overwhelmed by the many supportive and congratulatory messages my family and I received. The hours of planning and attention to detail that preceded the inauguration day are sincerely appre- ciated. I’m sure I will never experience anything like this again. Fortunately, the weather cooperated and allowed all of our guests to safely travel to Chadron. Thank you for the generous donations that have been and continue to be made to the Rhine Legacy Scholarship. Supporting student success is especially meaningful to me. Over the last few months I have gained a new appreciation for all of the presidents who came to Chadron State before me. And while they all no doubt had their challenges, it must have been a daunt- ing prospect for our first president, Joseph Sparks. With a promise of 80 acres from the City of Chadron, a $35,000 appropriation from the legislature, and a dream, Sparks began the journey of Chadron Normal. On June 5, 1911, the first group of faculty and 111 students started their first term. I believe this monumental effort established a legacy of cour- age in the face of change that resides on this campus today. -

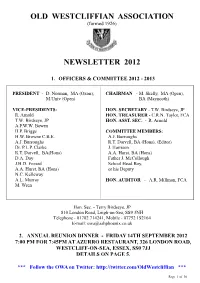

OWA Newsletter 2012 PDF File

OLD WESTCLIFFIAN ASSOCIATION (formed 1926) NEWSLETTER 2012 1. OFFICERS & COMMITTEE 2012 - 2013 PRESIDENT - D. Norman, MA (Oxon), CHAIRMAN - M. Skelly, MA (Open), M.Univ (Open) BA (Maynooth) VICE-PRESIDENTS: HON. SECRETARY - T.W. Birdseye, JP R. Arnold HON. TREASURER - C.R.N. Taylor, FCA T.W. Birdseye, JP HON. ASST. SEC. - R. Arnold A.P.W.W. Bowen H.P. Briggs COMMITTEE MEMBERS: H.W. Browne C.B.E. A.J. Burroughs A.J. Burroughs R.T. Darvell, BA (Hons), (Editor) Dr. P.L.P. Clarke J. Harrison R.T. Darvell, BA(Hons) A.A. Hurst, BA (Hons) D.A. Day Father J. McCollough J.H.D. Fozard School Head Boy, A.A. Hurst, BA (Hons) or his Deputy N.C. Kelleway A.L. Murray HON. AUDITOR - A.R. Millman, FCA M. Wren Hon. Sec. - Terry Birdseye, JP 810 London Road, Leigh-on-Sea, SS9 3NH Telephone - 01702 714241, Mobile - 07752 192164 E-mail: [email protected] 2. ANNUAL REUNION DINNER - FRIDAY 14TH SEPTEMBER 2012 7:00 PM FOR 7:45PM AT AZURRO RESTAURANT, 326 LONDON ROAD, WESTCLIFF-ON-SEA, ESSEX, SS0 7JJ DETAILS ON PAGE 5. *** Follow the OWA on Twitter: http://twitter.com/OldWestcliffian *** Page 1 of 36 Page 2 of 36 CONTENTS 1. Officers & Committee 2012 - 2013. 2. O.W.A Annual Reunion Dinner, Friday 14th September 2012 - 7:00 pm for 7:45 pm at Azurro Restaurant, 326 London Road, Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, SS0 7JJ. Details and reply slips on page 5. 3. (i) Honorary Secretary - Careers Guidance Support Form (ii) New Members (iii) Donations 4.