Why We Need a Relative Income Poverty Measure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remedy and Elimination of Tuberculosis” Akanksha Mishra [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Theses Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Winter 12-15-2017 A Novel Model of “Remedy and Elimination of Tuberculosis” Akanksha Mishra [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes Part of the Analytical, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Techniques and Equipment Commons, Diseases Commons, Epidemiology Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Other Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mishra, Akanksha, "A Novel Model of “Remedy and Elimination of Tuberculosis”" (2017). Master's Theses. 1118. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Novel Model of “Remedy and Elimination of Tuberculosis” By: Akanksha Mishra University of San Francisco November 21, 2017 MASTER OF ARTS in INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Novel Model of “Remedy and Elimination of Tuberculosis” MASTER OF ARTS in INTERNATIONAL STUDIES By AKANKSHA MISHRA December 18, 2017 UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Under the guidance and approval of the committee, and approval by all the members, this thesis project has been accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree. Adviser__________________________________ Date ________________________ Academic Director Date ________________________________________ ______________________ 2 ABSTRACT Tuberculosis (TB), is one of the top ten causes of death worldwide. -

HOW EDUCATION BREAKS the CYCLE of POVERTY: an INTER-REGIONAL STUDY of INDONESIAN HOUSEHOLDS by MASNIARITTA POHAN Sarjana Ekonomi

HOW EDUCATION BREAKS THE CYCLE OF POVERTY: AN INTER-REGIONAL STUDY OF INDONESIAN HOUSEHOLDS By MASNIARITTA POHAN Sarjana Ekonomi Universitas Katolik Parahyangan Bandung, Indonesia 2000 Magister Sains Perencanaan dan Kebijakan Publik Universitas Indonesia Depok, Indonesia 2003 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2013 HOW EDUCATION BREAKS THE CYCLE OF POVERTY: AN INTER-REGIONAL STUDY OF INDONESIAN HOUSEHOLDS Dissertation Approved: Dr. Jeffrey D. Vitale Dissertation Adviser Dr. Brian D. Adam Dr. Arthur L. Stoecker Dr. Keith D. Willett ii Name: MASNIARITTA POHAN Date of Degree: MAY, 2013 Title of Study: HOW EDUCATION BREAKS THE CYCLE OF POVERTY: AN INTER-REGIONAL STUDY OF INDONESIAN HOUSEHOLDS Major Field: AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS Abstract: The positive contribution of human capital to income has long been studied and shown to be significant. This study shows the importance of public spending on education in order to accelerate growth and reduce poverty. Results suggest that government expenditure on education programs can help overcome negative family socioeconomic conditions, leading to intergenerational improvement of income. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 Background ..............................................................................................................1 The Global -

Breaking the Cycle of Poverty in Young Families

POLICY REPORT | APRIL 2015 Breaking the Cycle of Poverty in Young Families TwO-GEneration Policy RecommEnd ations The two-generation approach is a poverty reduction strategy meeting the unique needs of both parents and children simultaneously, which differs from other models that provide service provision to parents or their children separately. The focus of this two-generation research was specifically young families, which are defined as out-of-school, out-of-work youth 15–24 with dependent children under the age of 6. Families in poverty can best be served by addressing parental needs for education, workforce training, and parental skills, while also addressing child development essentials. The recent economic downturn has tremendously impacted communities and families in the United States, especially young families. Over 1.4 million youth ages 15–24 are out-of-school, out-of-work and raising dependent children. When youth are out of the education system, lack early work experience, and cannot find employment, it is unlikely that they will have the means to support themselves.1 Too often, this traps their families in a cycle of poverty for generations. With generous support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation and ASCEND at the Aspen Institute, the National Human Services Assembly (NHSA), an association of America’s leading human service nonprofit organizations, set out to identify policy and administrative barriers to two- generation strategies. The NHSA engaged its member organizations and local affiliates to better understand their two-generation programs, challenges to success, and strategies for overcoming. It also convened advo- cates, experts, and local providers together to determine the appropriate government strategies to break the cycle of poverty in young families. -

Policy Brief 1 Breaking the Vicious Cycle of Mental Ill-Health and Poverty

proving me Im nt al h e a l Policy brief 1 t h , R e d u c i Breaking the vicious cycle of n g p o mental ill-health and poverty v e r t y Mental Health and Poverty Project g pov ucin erty ed , R h lt a e h l a t n The purpose of the Mental Health and Poverty Project is to develop, implemente and evaluate mental m health policy in poor countries, in order to provide new knowledge regarding comprehensive multi- g n sectoral approaches to breaking the negative cycle of i poverty and mental ill-health. v o r p m I proving me Im nt al h e a l t h , R e Breaking the vicious cycle of mental ill-health and poverty d u c i n g p o v e r t The Mental Health and Poverty Project living in poverty, such as low socio-economic status, exposure y (MHaPP) to stressful life events (such as crime and violence), inadequate housing, unemployment and social conflict, are linked to mental There is growing recognition that mental health is a crucial ill-health. Poverty is also associated with exclusion, isolation, public health and development issue in South Africa. feelings of disempowerment, helplessness and hopelessness, Neuropsychiatric conditions rank 3rd in their contribution to the which can lead to chronic insecurity and social mistrust, burden of disease in SA1 and 16.5% of South Africans report affecting people’s mental well being. As the mental well being having suffered from mental disorders in the last year.2 The of individuals is eroded by poverty, the available energies within Mental Health and Poverty Project, a ground-breaking research communities to contribute to nation-building are reduced. -

Working out of Poverty

REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR-GENERAL WORKING OUT OF POVERTY INTERNATIONAL LABOUR CONFERENCE 91st Session 2003 INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE GENEVA This Report may also be consulted on the ILO Internet site (http://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc91/pdf/rep-i-a.pdf). ISBN 92-2-112870-9 ISSN 0074-6681 First published 2003 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. ILO publications can be obtained through major booksellers or ILO local offices in many countries, or direct from ILO Publications, International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. Catalogues or lists of new publications are available free of charge from the above address. Photocomposed by the International Labour Office, Geneva, Switzerland DTP Printed in Switzerland SRO Preface This is my third opportunity to offer the Director-General’s Report to the International Labour Conference. The first, Decent work, 1 revisited our mandate, interpreted it and defined our mission for the world of today, based on ILO values. You subscribed to the agenda we set out, which af- firmed that the ILO had to be concerned with all workers, including those beyond the formal labour market. -

1 Why Research Infectious Diseases of Poverty?

1 Why research infectious diseases of poverty? 11 in chapteR 1: • Poverty and infectious disease – a problematic relationship • infectious disease – the true burden on communities • the value of research: new ways to end old diseases • moving beyond the Millennium Development Goals • the cost of inaction – social and economic consequences • tackling disease – a need for investment • ten reasons to research infectious diseases of poverty AUTHORS Research is the key to making things Professor SiAn GRiffiths happen for poor populations. This Director, School of Public Health introductory chapter of the Global and Primary Care, The ChineSe Report examines the need for research univerSity of Hong Kong, Hong into the infectious diseases that Kong SPecial AdminiStrative region, China disproportionately affect poor and marginalized communities – the so- Professor Xiao-NonG Zhou Director, National InStitute called “infectious diseases of poverty”. of ParaSitic DiSeaSeS, ChineSe It examines the link between poverty center for DiSeaSe Control anD and disease and outlines ten reasons Prevention, Shanghai, China to support research for such diseases. Such research represents unfinished Report fellOw Allison Thorpe business of global relevance, work that the world can no longer afford to neglect. 11 According to the latest published data in 2012, infectious (including parasitic) diseases were together responsible for the death of more than 8.7 million people worldwide in 2008 (1). The majority of these deaths were of poor people living in low and middle- income countries, with many of the deaths Infectious diseases have occurring in children under five years of age. shaped societies, driven Given the sketchy data, misdiagnosis and conflict and spawned the under-detection that are typical of health marginalization of infected systems in impoverished areas, these num- individuals and communities bers are almost certainly underestimated. -

Poverty Alleviation in China: a Lesson for the Developing World?

Poverty Alleviation in China: A Lesson for the Developing World? Gerhard K. Heilig(1) / Zhang, Ming(2) / Long, Hualou(2) Li, Xiubin(3) / Wu, Xiuqin(4) December 27, 2005 Part of this paper was presented at the International Conference on the West Development and Sustainable Development August 2-4, 2005 Urumqi, China 1 The title photo depicts the “traditional muslim market” in Urumqi - complete with a huge Carrefour market, KFC fastfood restaurant, and open food court. In the background the recently renovated mosque. The photo was taken in August 2005 by Gerhard K. Heilig. (1) Senior Research Scholar, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Leader of the Research Activity on Sustainable Rural Development (SRD) and Professor for China Studies, Vienna University. (2) Research Scholar, IIASA, SRD-Research; (3) Deputy Head, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research (IGSNRR), Chinese Academy of Sciences. (4) Associate Professor, College of Soil and Water Conservation, Beijing Forestry University. Correspondence to: Gerhard K. Heilig, Neulinggasse 16, A-1030 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: [email protected] This document can be downloaded from: www.gerhard-k-heilig.com 2 Introduction - China’s Rural Development With Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the late 1970s China started its spectacular transi- tion from a state-run economy, based on centralized command and control, to a modern eco- nomic system based on market principles and international cooperation. The first phase in these reforms was the introduction of the “household responsibility system” in the early 1980s, which essentially abandonded the system of communal farming and re-established the autonomy of the individual farm household. -

Poverty and Sustainable Socio-Economic Development in Africa: the Nigeria Experience

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal November edition vol. 8, No.26 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 POVERTY AND SUSTAINABLE SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA: THE NIGERIA EXPERIENCE Akhakpe Ighodalo, PhD Department Of Public Administration, Lagos State University, Ojo Abstract The paper argues that poverty has remained a major obstacle to sustainable development and democracy in the global South. With the return to civil rule in 1999 in Nigeria, hopes were high that the return to democracy will stem the decline of the economy and provide the citizenry with the social dividends of democracy. More than a decade after the economy is still on it’s kneels with more than half of the population living on less than one dollar per day. With the use of dependency theory the paper posited that unless the people are empowered to make choices and participate in making decisions that affects their lives sustainable socio- economic development will remain elusive in Africa in general and Nigeria in particular. Keywords: Poverty, Sustainable development, Africa, Nigeria Introduction The global south has one thing in common. It is the ravaging plague of poverty that has stunted the ability of its people to transform themselves and environment in order to a state create of continuous improvement in their human and physical conditions of life. While the phenomenon of poverty is not restricted to countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, countries in Africa attract more concerns because of the peculiar challenges they face which limit their abilities to tackle this recurring decimal in the life of people and their nations. -

ABSTRACT the FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE the EFFECTIVENESS of POVERTY ALLEVIATION PROGRAMS in NIGERIA Nigeria Has Had a Long Fight Wi

ABSTRACT THE FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF POVERTY ALLEVIATION PROGRAMS IN NIGERIA by Roseline Jindori Yunusa Nigeria has had a long fight with poverty since its independence, various policies and poverty alleviation programs have been put in place with the goal to eradicate poverty; however they have not yielded the expected result. The goal of this qualitative study was to investigate the claim by beneficiaries that poverty alleviation programs do not solve the poverty situation in Nigeria, in addition explore the reasons they gave for why programs have not been successful, and what could make them more successful. There is a general feeling of frustration and lack of confidence in government organized programs, stemming from policy formulation and in appropriately targeting the poor. The problems of poverty alleviation programs as seen by this study are that, policy makers have no knowledge about the culture of poverty or the emotional preparedness that people need to break family generation cycle of poverty and ultimately transition out of poverty. THE FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE EFFECTIVENESS OF POVERTY ALLEVIATION PROGRAMS IN NIGERIA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Department of Family Studies and Social Work by Roseline Jindori Yunusa Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2012 Advisor…………………………. Sherrill L. Sellers PhD Reader………………………… Katherine A. Kuvalanka, PhD Reader………………………….. Kevin R. Bush, PhD Table of Contents TABLE -

Measuring Child Poverty by the Rothbarth Scales: Estimates for an Urban Chinese

1 Measuring Child Poverty by the Rothbarth Scales: Estimates for an Urban Chinese East Coast Province Feridoon Koohi-Kamali and Yibin Liu Abstract The commonly employed Engel method of poverty measurement, based on the budget share of food, is known to lead to a large overestimation of age-specific poverty. This paper applies an alternative model based on variations in adults’ living standard that offers a particularly effective method of obtaining age-specific poverty measures, especially for children. However, only a few studies using this alternative model are available. This paper contributes to that small body of studies based on the latter model by applying it to two urban surveys from an east coast province of China for 2002 and 2009. We obtain measures of child poverty that have plausible values in size when compared to those reported for other studies using the same method. Our results indicate that the extremely high Chinese rates of economic growth during 2002-09 have had only a modest impact on child poverty, and an almost negligible impact on extreme child poverty. The paper points to rising urban inequality as the most likely explanation of the results obtained. 2 Preliminary Draft Please Do Not Quote Measuring Child Poverty by the Rothbarth Scales: Estimates for an Urban Chinese East Coast Province1 Feridoon Koohi-Kamali and Yibin Liu, Department of Economics, Franklin & Marshall College, PA. October 2013 1. Introduction Child poverty reinforces the endless cycle of poverty. Children born into poor families are likely to suffer from poor health, poor education, and low skills, with serious impact on their labor market earning in adulthood. -

Addressing Poverty in Tb Control

ADDRESSING POVERTY IN TB CONTROL options for national tb control programmes WHO/HTM/TB/2005.352 ADDRESSING POVERTY IN TB CONTROL OPTIONS FOR NATIONAL TB CONTROL PROGRAMMES © World Health Organization 2005 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concern- ing the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a sim- ilar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary prod- ucts are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the infor- mation contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication. CONTENTS | 3 CONTENTS PREFACE . 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 6 SUMMARY . 7 INTRODUCTION . 10 CHAPTER 1. Rationale for integrating pro-poor and equity- enhancing measures in TB control . 12 CHAPTER 2. Barriers to accessing TB services by poor and vulnerable groups . 21 CHAPTER 3. -

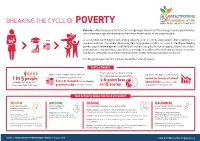

Breaking the Cycle of Poverty

BREAKING THE CYCLE OF POVERTY Poverty is affected by several factors including hunger and malnutrition. Hunger pushes poor families into a downward spiral and prevents them from breaking out of the poverty cycle. A sustainable world begins with ending poverty in all its forms everywhere. Breastfeeding is a universal solution that levels the playing field to give every child a fair start in life. Breastfeeding powers cognitive development and the IQ of children, thus greatly improving educational attainment, participation in the workforce and lifetime earnings. It enables millions of young children to survive and thrive, setting them on a path towards better health and a more prosperous future. It is the great equaliser that can help break the cycle of poverty. FACTS & FIGURES Shorter durations of breastfeeding Breastfeeding is one of the best Not breastfeeding is associated with for children were associated with a investments in global health. 1 in 5 people 2.6-point loss economic losses of about in developing regions still Every $1 invested in breastfeeding $302 billion annually or 0.49% live on less than $1.90 a day generates $35 in economic returns in IQ scores of world gross national income TAKE ACTION TO BREAK THE CYCLE OF POVERTY INFORM ANCHOR ENGAGE GALVANISE people about the links breastfeeding as the with individuals and organisations for greater impact action to advance breastfeeding as between poverty reduction foundation of life a part of poverty reduction and breastfeeding Engage organisations that work on nutrition, hunger, food security, Integrate breastfeeding into food aid, environment, climate change, and poverty reduction issues.