Psychotherapy in Neurorehabilitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurological Principles and Rehabilitation of Action Disorders: Rehabilitation Interventions

Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair Neurological Principles and Supplement to 25(5) 33$--435 ©TheAuthor(s) 2011 Reprints and permission: http://W'NW. Rehabilitation of Action Disorders: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOl: 10.1 1771154596831 1410942 Rehabilitation Interventions http://nnr.sagepub.com ®SAGE I 3 Valerie Pomeroy, PhD , Salvatore M. Aglioti, MD\ VictorW. Mark, MD , 4 6 Dennis McFarland, PhD , Cathy Stinear, PhD\ Steven L. Wolf, PhD , 7 7 Maurizio Corbetta, MD , and Susan M. Fitzpatrick, PhD ,8 This third chapter discusses the evidence for the rehabilitation of the most common movement disorders of the upper extremity. The authors also present a framework, building on the computation, anatomy, and physiology (CAP) model, for incorporating some of the principles discussed in the 2 previous chapters by Frey et al and Sathian et al in the practice of rehabilitation and for discussing potentially helpful interventions based on emergent neuroscience principles. Introduction General Principles for Delivery of Therapy Interventions Much of the evidence-based body of knowledge informing upper-limb rehabilitation has been generated from research Delivery of therapy interventions is multifaceted, and certain with patients recovering from stroke. It is not srnprising, general principles should be considered in each patient: given the number of affected individuals worldwide, that stroke would serve as the dominant model. However, many 1, The establishment of a 'contract' between people principles informing neurorehabilitation interventions can with neurological deficits and their therapy team. be translated from stroke into interventions for other neuro 2. Analysis of behavioral deficits in relation to known logical conditions when appropriate. principles of brain organization. -

Occupational Therapy Consensus Recommendations for Functional Neurological Disorder

Occasional essay J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp-2019-322281 on 30 July 2020. Downloaded from Occupational therapy consensus recommendations for functional neurological disorder Clare Nicholson ,1 Mark J Edwards,2 Alan J Carson,3 Paula Gardiner,4 Dawn Golder,5 Kate Hayward,1 Susan Humblestone,6 Helen Jinadu,7 Carrie Lumsden,8 Julie MacLean,9 Lynne Main,10 Lindsey Macgregor,11 Glenn Nielsen,2 Louise Oakley,12 Jason Price,13 Jessica Ranford,9 Jasbir Ranu,1 Ed Sum,14 Jon Stone 3 ► Additional material is ABSTRact jerks and dystonia), sensory symptoms, cognitive published online only. To view Background People with functional neurological deficits and seizure-like events (commonly known please visit the journal online as dissociative seizures or non- epileptic seizures). (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ disorder (FND) are commonly seen by occupational jnnp- 2019- 322281). therapists; however, there are limited descriptions in the Fatigue and persistent pain are also commonly literature about the type of interventions that are likely experienced as part of the disorder. Symptoms For numbered affiliations see to be helpful. This document aims to address this issue by can present acutely and resolve quickly or can be end of article. providing consensus recommendations for occupational long lasting. Regardless of duration, those affected therapy assessment and intervention. frequently experience high levels of distress, Correspondence to Methods The recommendations were developed in four disability, unemployment, social care utilisation and Mrs Clare Nicholson, Therapy 2 Services, University College stages. Stage 1: an invitation was sent to occupational reduced quality of life. The stigma associated with London Hospitals NHS therapists with expertise in FND in different countries to FND contributes to the burden of the diagnosis.3 Foundation Trust National complete two surveys exploring their opinions regarding OT is generally recognised as an integral part Hospital for Neurology and best practice for assessment and interventions for FND. -

The Role of Spasticity in Functional Neurorehabilitation- Part I: The

Research article iMedPub Journals ARCHIVES OF MEDICINE 2016 http://www.imedpub.com/ Vol.8 No.3:7 ISSN 1989-5216 The Role of Spasticity in Functional Neurorehabilitation- Part I: The Pathophysiology of Spasticity, the Relationship with the Neuroplasticity, Spinal Shock and Clinical Signs Angela Martins* Department of Veterinary Science, Lusophone University of Humanities and Technology, Hospital Veterinário da Arrábida, Portugal *Corresponding author: Angela Martins, Department of Veterinary Science, Lusophone University of Humanities and Technology, Hospital Veterinário da Arrábida, Portugal, Tel: 212181441; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: Feb 29, 2016; Acc date: Apr 05, 2016; Pub date: April 12, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Martins A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Citation: Martins A. The Role of Spasticity in Functional Neurorehabilitation- Part I: The Pathophysiology of Spasticity, the Relationship with the Neuroplasticity, Spinal Shock and Clinical Signs. Arch Med. 2016, 8:3 the quadrupeds spinal cord injuries are predominantly thoraco-lumbar [6] due to the discontinuity of the intercapital Abstract ligament [6], the clinical sign of spasticity is frequently addressed in functional neurorehabilitation (FNR) [7-9]. The symptom/clinical sign of spasticity is extremely Spasticity both on the biped and quadruped usually develops important in functional neurorehabilitation, since it in the antigravity muscles. reduces the functional independence both in the quadruped animal as in the human biped. In the human biped, spasticity appears in the upper- extremity flexor muscles as result of a stroke, whereas an This clinical sign/symptom manifests itself alonside with excessive muscle spasm is in the lower extremity extensor pain, muscle weakness, impaired coordination and poor muscles is secondary to SCI. -

Brain-Machine Interface: from Neurophysiology to Clinical

Neurophysiology of Brain-Machine Interface Rehabilitation Matija Milosevic, Osaka University - Graduate School of Engineering Science - Japan. Abstract— Long-lasting cortical re-organization or II. METHODS neuroplasticity depends on the ability to synchronize the descending (voluntary) commands and the successful execution Stimulation of muscles with FES was delivered using a of the task using a neuroprosthetic. This talk will discuss the constant current biphasic waveform with a 300μs pulse width neurophysiological mechanisms of brain-machine interface at 50 Hz frequency via surface electrodes. First, repetitive (BMI) controlled neuroprosthetics with the aim to provide transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) intermittent theta implications for development of technologies for rehabilitation. burst protocol (iTBS) was used to induce cortical facilitation. iTBS protocol consists of pulses delivered intermittently at a I. INTRODUCTION frequency of 50 Hz and 5 Hz for a total of 200 seconds. Functional electrical stimulation (FES) neuroprosthetics Moreover, motor imagery protocol was used to display a can be used to applying short electric impulses over the virtual reality hand opening and closing sequence of muscles or the nerves to generate hand muscle contractions movements (hand flexion/extension) while subject’s hands and functional movements such as reaching and grasping. remained at rest and out of the visual field. Our work has shown that recruitment of muscles using FES goes beyond simple contractions, with evidence suggesting III. RESULTS re-organization of the spinal reflex networks and cortical- Our first results showed that motor imagery can affect level changes after the stimulating period [1,2]. However, a major challenge remains in achieving precise temporal corticospinal facilitation in a phase-dependent manner, i.e., synchronization of voluntary commands and activation of the hand flexor muscles during hand closing and extensor muscles [3]. -

Brain-Computer Interfaces in Neurological Rehabilitation

British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine Brain-Computer Interfaces in neurological rehabilitation Essay Prize Submission 2013 Kundan Iqbal Newcastle University BSRM Essay Prize Submission 2013 Kundan Iqbal During my third year clinical rotations, I met Melissa1, a 12 year old who suffered a haemorrhagic stroke caused by an undetected brain tumour, which left her suffering with locked-in syndrome (LIS). LIS is a rare condition caused by brainstem damage resulting in sudden quadriplegia (sometimes sparing ocular muscles), with preserved consciousness and cognition. Sufferers are left severely limited. Meeting Melissa initiated my interest in therapies to improve the abilities and function of those with severe neuromuscular disorders including LIS. 1 Name and age has been changed to preserve anonymity 1 BSRM Essay Prize Submission 2013 Kundan Iqbal INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................3 WHAT ARE BCIS? ......................................................................................................................................................................3 TYPES OF BRAIN SIGNALS........................................................................................................................................................3 HOW DO BCIs WORK?.............................................................................................................................................................5 -

Neurorehabilitation in MS the Rôle of Neuroplasticity Jürg Kesselring

Disclosure & declaration of interests Prof. Dr. med. Jürg Kesselring, FRCP Head of the Department of Neurology and Neurorehabilitation Rehabilitation Centre Valens CH-7317 Valens Switzerland Tel +41 (0)81 303 14 08 www.kliniken-valens.ch • Interest in resilience since birth (uplifting forces) • applied learning since school age (uninterrupted since) • practicing & rehearsing music (cello) since november 1960 • applying neuroplasticity to neurological patients in Valens (& elsewhere) since july 1987 • teaching Clinical Neuroscience at Centre of Neuroscience University Zürich since 1999 • DMC FTY/BAF studies (Novartis) since 2005 • Member of ICRC (since 1.1.11) • First Honorary President of Swiss MS Society Recovery mechanisms: diaschisis (von Monakow 1914) A process in which neurons function abnormally because influences necessary to their normal functions have been removed by damage to neurons to which they have been connected Neuroplasticity – the flexible brain Legal basis forGesetzliche neurorehabilitation Grundlagen in Switzerland Base legale KVG Art. 32 Medical applications must be effective appropriate economic effectiveness must be determined and proven by scientific methods Neurorehabilitation Valens (1987 - 2015) N= 373 – 2565 (+687%) Multiple Sclerosis 0 - 652 (+%) stroke 105/124 -796 (+247%) ischemia haemorrhage Tumor 5-89 (+1680%) Trauma+ others 22/40 - 449 (+624%) Parkinson 0-188 (+ %) Epilepsy 0-118 + % Peripheral 14-213 +1421% Multiple Sclerosis: longterm disease course Age 53-57 years RR: after 22,1 years PP: after 9,6 -

Neuroplasticity & Implications for Stroke Recovery

4/6/2016 Neuroplasticity Mechanisms: Selected Neural Plasticity References How Therapy Changes the Brain • Bryck & Fisher (2012) Training the Brain: Practical Applications of Neural Plasticity From the Intersection of Cognitive Neuroscience, Developmental Psychology and Prevention Science. Am Psychol. 67(2): 87–100 Review as applied to perdiatrics After Injury Part 2 • Kerr, AL, Cheng, SY, Jones, TA (2011) - Experience-dependent neural plasticity in the adult damaged brain. Commun Disord. 44(5): 538–548 • Kleim, Jeffrey (2011) Neural plasticity and neurorehabilitation: Teaching the new MSHA brain old tricks. Journal of communication disorders, 44(5) • Kleim, J. and Jones, T.A. (2008) Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity. JSHR 51(1), S225-S239. • Murphy & Corbett (2009) Plasticity during stroke recovery: from synapse to Martha S. Burns, Ph.D. behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience • Pekna,M., Pekny, M., Nilsson,M.(2012) Modulation of Neural Plasticity as a Basis Joint Appointment for Stroke Rehabilitation. Stroke 43: 2819-2828 Thorough review for all disciplines Professor • Takeuchi, N & Izumi, S (2013) Rehabilitation with Poststroke Motor Recovery: A Review with a Focus on Neural Plasticity. Stroke Research and Treatment. Volume Northwestern University 2013, Article ID 128641 Excellent review for PT and OT • Warraich Z, Kleim JA. (2010) Neural plasticity: the biological substrate for neurorehabilitation. PM R. 2:S208 –S219. , References – EB task specific References on Recovery procedures • Corbetta M, Kincade MJ, Lewis C, Snyder AZ, Sapir A. (2005) Neural basis and • Harris, J., Eng, J., Miller, W., Dawson, A.(2009) A Self- recovery of spatial attention deficits in spatial neglect. Nature Neuroscience 8:1603-10. Administered Graded Repetitive Arm Supplementary • Castellanos, N et al. -

CLF Vita (08-19)

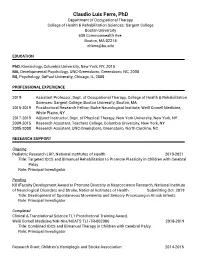

Claudio Luis Ferre, PhD Department of Occupational Therapy College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College Boston University 635 Commonwealth Ave. Boston, MA 02215 [email protected] EDUCATION PhD, Kinesiology, Columbia University, New York, NY, 2015 MA, Developmental Psychology, UNC-Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, 2008 BS, Psychology, DePaul University, Chicago, IL, 2005 June 2005 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2019- Assistant Professor, Dept. of Occupational Therapy, College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College, Boston University, Boston, MA 2015-2019 Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Burke Neurological Institute, Weill Cornell Medicine, White Plains, NY 2017-2019 Adjunct Instructor, Dept. of Physical Therapy, New York University, New York, NY 2009-2015 Research Assistant, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY 2005-2008 Research Assistant, UNC-Greensboro, Greensboro, North Carolina, NC RESEARCH SUPPORT Ongoing Pediatric Research LRP, National Institutes of Health 2019-2021 Title: Targeted tDCS and Bimanual Rehabilitation to Promote Plasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy Role: Principal Investigator Pending K01Faculty Development Award to Promote Diversity in Neuroscience Research, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health Submitting Oct. 2019 Title: Development of Spontaneous Movements and Sensory Processing in At-risk Infants Role: Principal Investigator Completed Clinical & Translational Science TL1 Postdoctoral Training Award, Weill Cornell Medicine/NIH NIH/NCATS -

2019 Neurorehabilitation

NeuroRehabilitation June 13-15 • Waltham, MA 2019 This course sold out the last two years. Early registration is strongly advised. Stroke • Concussion • TBI • SCI • Degenerative Neurological Diseases State-of-the-Art Rehabilitation Strategies and Practices to: • Accelerate recovery • Improve clinical skills • Reduce symptoms • Advance patient well-being • Elevate patients to their maximum level of function Updates, Innovations, and Best Practices for Earn up to 17.25 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ Physiatrists PTs Neuropsychologists Neurologists OTs Clinical Psychologists Psychiatrists SLPs Mental Health Counselors This educational activity will Internists NPs Clinical Social Workers be submitted for continuing Geriatricians PAs Case Managers education credits (CEUs) Family Physicians Nurses Register at NeuroRehab.HMSCME.com COURSE DIRECTORS Dear Colleague, Patients with stroke, TBI, SCI, and degenerative neurological diseases face significant disruption to so many facets of their lives, and clinicians are left with so many treatment dimensions to consider, that rehabilitation Ross Zafonte, DO is never simple. These challenges are compounded by the fact that rehabilitation approaches are now in a period of rapid expansion. It’s difficult to stay current with, choose, and use the best options for neurorehabilitation—yet this is key to optimizing patient outcomes. It’s with these challenges in mind that we provide this annual program: NeuroRehabilitation 2019. Many of the country’s most experienced and committed neurorehabilitation experts will present practical, cutting- Mel Glenn, MD edge clinical interventions to further your expertise in guiding patients to their maximum level of function. Participants will learn of state-of-the-art research and ASSISTANT COURSE its application to clinical practice in such diverse topics DIRECTORS as exercise, pharmacology, technology, wellness, patient motivation, and caregiver assistance. -

A Review of Neuromodulation in the Neurorehabilitation

l of rna Neu ou ro Yin and Slavin, Int J Neurorehabilitation Eng 2015, 2:1 J r l e a h a n b International DOI: 10.4172/2376-0281.1000151 o i i t l i t a a n t r i o e t n n I ISSN: 2376-0281 Journal of Neurorehabilitation Review Article Open Access A Review of Neuromodulation in the Neurorehabilitation Dali Yin and Konstantin V Slavin* Department of Neurosurgery, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA Abstract For many years, invasive neuromodulation has been used in neurorehabilitation, mainly in treatment of movement disorders and various psychiatric conditions. Use of deep brain stimulation and other implanted electrical stimulators is being explored in other conditions, such as stroke, traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. This paper provides a review of the possible role of Neuromodulation in neurorehabilitation and highlights some of its applications for patients with various neurological conditions. Since most of the existing findings are based on animal studies, preliminary data, case reports and poor-controlled studies, further investigations including research and clinical trials are necessary to increase the applications of neurostimulation in the field of neurorehabilitation. Keywords: Neuromodulation; Neurorehabilitation; Stroke; rehabilitation constantly improves motor function in ratsfollowing Traumatic brain injury; Spinal cord injury; Epilepsy motor cortex injury [10-11]. Introduction Motor Cortex Stimulation Neurorehabilitation is a complicated medical process; its goal is to A small randomized clinical trial [n=24] found that Motor Cortex help patients to recover from injuries or abnormalities in the Central Stimulation [MCS] lead to motor and functional improvements Nervous System [CNS], and to compensate for functional deficits if [difference of Fugl-Meyer motor scores in estimated means = 3.8, p = possible. -

Neurorehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis – Resilience in Practice

Review Multiple Sclerosis Neurorehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis – Resilience in Practice Jürg Kesselring Department of Neurology and Neurorehabilitation Rehabilitation Centre, Valens, Switzerland DOI: https://doi.org/10.17925/ENR.2017.12.01.31 n recent years, enormous strides have been made in increasing the range and efficacy of disease-modifying drugs available for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) in its early and remitting stages, and more continue to emerge. Another equally important concept I of successful treatment of MS is neurorehabilitation, which must be pursued alongside these medications. Key factors that contribute to the impact of neurorehabilitation include resilience and neuroplasticity. In the former, components such as nutrition, self-belief and physical activity provide a stronger response to the disease and improved responses to treatment. Neuroplasticity is the capacity of the brain to establish new neuronal networks after lesion damage has occurred and distant brain regions assume control of lost functions. In MS, it is vital that each patient is treated by a coordinated multidisciplinary team. This enables all aspects of the disease including problems with mobility, gait, bladder/bowel disturbances, fatigue and depression to be effectively treated. It is also important that the treating team adopts current best practice and provides internationally agreed standards of care. A further vital aspect of MS management is patient engagement, in which individuals are fully involved and are encouraged to strive and put effort into meeting treatment goals. In this approach, healthcare providers become motivators and patients need less intervention and consume fewer resources. Numerous interventions that promote neurorehabilitation are available, though evidence to support their use is limited by a lack of data from large randomised controlled trials. -

Exploring the Use of Brain-Computer Interfaces in Stroke Neurorehabilitation

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2021, Article ID 9967348, 11 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9967348 Review Article Exploring the Use of Brain-Computer Interfaces in Stroke Neurorehabilitation Siyu Yang,1 Ruobing Li,1 Hongtao Li,1,2 Ke Xu,1 Yuqing Shi,1 Qingyong Wang ,1 Tiansong Yang ,1,2,3 and Xiaowei Sun 1,2 1Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, 24 Heping Road, Xiangfang District, Harbin, China 8615-0040 2First Affiliated Hospital, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, 26 Heping Road, Xiangfang District, Harbin, China 8615- 0040 3Shenzhen People’s Hospital, Second Clinical Medical College of Jinan University, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Shenzhen 518120, China Correspondence should be addressed to Tiansong Yang; [email protected] and Xiaowei Sun; [email protected] Received 20 March 2021; Accepted 4 June 2021; Published 19 June 2021 Academic Editor: Wen Si Copyright © 2021 Siyu Yang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. With the continuous development of artificial intelligence technology, “brain-computer interfaces” are gradually entering the field of medical rehabilitation. As a result, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have been included in many countries’ strategic plans for innovating this field, and subsequently, major funding and talent have been invested in this technology. In neurological rehabilitation for stroke patients, the use of BCIs opens up a new chapter in “top-down” rehabilitation. In our study, we first reviewed the latest BCI technologies, then presented recent research advances and landmark findings in BCI-based neurorehabilitation for stroke patients.