Rubens and His Spanish Patrons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ontdek Schilder, Tekenaar, Prentkunstenaar Otto Van Veen

79637 4 afbeeldingen Otto van Veen man / Noord-Nederlands, Zuid-Nederlands schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, hofschilder Naamvarianten In dit veld worden niet-voorkeursnamen zoals die in bronnen zijn aangetroffen, vastgelegd en toegankelijk gemaakt. Dit zijn bijvoorbeeld andere schrijfwijzen, bijnamen of namen van getrouwde vrouwen met of juist zonder de achternaam van een echtgenoot. Vaenius, Octavius Vaenius, Otho Vaenius, Otto Veen, Octavius van Veen, Otho van Venius, Octavius Venius, Otho Venius, Otto Kwalificaties schilder, tekenaar, prentkunstenaar, hofschilder Nationaliteit/school Noord-Nederlands, Zuid-Nederlands Geboren Leiden 1556 Thieme/Becker 1940; according to Houbraken 1718: born in 1558 Overleden Brussel 1629-05-06 Houbraken 1718, vol. 1, p. Rombouts/Van Lerius 1872/1961, vol.1, p. 375, note 3 Familierelaties in dit veld wordt een familierelatie met één of meer andere kunstenaars vermeld. son of Cornelis Jansz. van Veen (1519-1591) burgomaster of Leyden and Geertruyd Simons van Neck (born 1530); marrried with Maria Loets/Loots/Loos (Duverger 1992, vol. 6, p. 186-187); brother of Gijsbert, Pieter, Artus and Aechtjen Cornelis; father of Gertrude van Veen; his 6-year old son Cornelis was buried on 19 September 1605 in St. Jacob's Church Zie ook in dit veld vindt u verwijzingen naar een groepsnaam of naar de kunstenaars die deel uitma(a)k(t)en van de groep. Ook kunt u verwijzingen naar andere kunstenaars aantreffen als het gaat om samenwerking zonder dat er sprake is van een groep(snaam). Dit is bijvoorbeeld het geval bij kunstenaars die gedeelten in werken van een andere kunstenaar voor hun rekening hebben genomen (zoals bij P.P. -

Map As Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira's 1656 Representation of Madrid

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Map as Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira's 1656 Representation of Madrid Jesús Escobar To cite this article: Jesús Escobar (2014) Map as Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira's 1656 Representation of Madrid, The Art Bulletin, 96:1, 50-69, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2014.877305 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2014.877305 Published online: 25 Apr 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 189 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Download by: [Northwestern University] Date: 22 September 2016, At: 08:04 Map as Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira’s 1656 Representation of Madrid Jesus Escobar “Mantua of the Carpentana, or Madrid, Royal City” reads the attributed to the overreach of Philip IV’s royal favorite and Latin inscription on the banderole that hovers above Pedro prime minister, Gaspar de Guzman, the count-duke of Teixeira’s monumental map of the Spanish capital, the Topo- Olivares (1587–1645). In 1640, in the midst of the Thirty graphia de la Villa de Madrid (Topography of the town of Years’ War, rebellions arose in Catalonia and Portugal, com- Madrid) (Fig. 1). The text refers to a place from the distant pounding the monarchy’s ongoing financial crises and lead- Roman past, the purported origin of Madrid, as well as the ing to Olivares’s ouster. -

Isabel Clara Eugenia and Peter Paul Rubens’S the Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series

ABSTRACT Title of Document: PIETY, POLITICS, AND PATRONAGE: ISABEL CLARA EUGENIA AND PETER PAUL RUBENS’S THE TRIUMPH OF THE EUCHARIST TAPESTRY SERIES Alexandra Billington Libby, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archeology This dissertation explores the circumstances that inspired the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, Princess of Spain, Archduchess of Austria, and Governess General of the Southern Netherlands to commission Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series for the Madrid convent of the Descalzas Reales. It traces the commission of the twenty large-scale tapestries that comprise the series to the aftermath of an important victory of the Infanta’s army over the Dutch in the town of Breda. Relying on contemporary literature, studies of the Infanta’s upbringing, and the tapestries themselves, it argues that the cycle was likely conceived as an ex-voto, or gift of thanks to God for the military triumph. In my discussion, I highlight previously unrecognized temporal and thematic connections between Isabel’s many other gestures of thanks in the wake of the victory and The Triumph of the Eucharist series. I further show how Rubens invested the tapestries with imagery and a conceptual conceit that celebrated the Eucharist in ways that symbolically evoked the triumph at Breda. My study also explores the motivations behind Isabel’s decision to give the series to the Descalzas Reales. It discusses how as an ex-voto, the tapestries implicitly credited her for the triumph and, thereby, affirmed her terrestrial authority. Drawing on the history of the convent and its use by the king of Spain as both a religious and political dynastic center, it shows that the series was not only a gift to the convent, but also a gift to the king, a man with whom the Infanta had developed a tense relationship over the question of her political autonomy. -

Four Tapestries After Hieronymus Bosch Author(S): Otto Kurz Source: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes , 1967, Vol

Four Tapestries after Hieronymus Bosch Author(s): Otto Kurz Source: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes , 1967, Vol. 30 (1967), pp. 150- 162 Published by: The Warburg Institute Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/750740 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Warburg Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes This content downloaded from 132.198.50.13 on Thu, 25 Feb 2021 15:18:23 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms FOUR TAPESTRIES AFTER HIERONYMUS BOSCH By Otto Kurz he first modern biographers of Hieronymus Bosch, Carl Justi and Hermann Dollmayr, knew from F6libien (1685) about the existence of a tapestry after a design by the artist, which was once in the Royal Gardemeuble at Paris, and they had heard rumours about other tapestries after Bosch in the Spanish Royal Collection.' It was natural to assume that Bosch, like so many other Netherlandish painters, had designed tapestries. When in 190o3 the Conde V. de Valencia de Don Juan published, in good reproductions, the magnificent collection of tapestries belonging to the Spanish Crown,2 it became obvious that the tapestries connected with Bosch, although still dating from the sixteenth century, must have been woven a considerable time after the death of the artist (Pls. -

Learned Love Sance

The emblem is a wonderful invention of the Renais- Learned Love sance. The funny, mysterious, moralizing, learned or pious combinations of word and image in the Learned Love crossover emblematic genre can be characterized as a delicate network of motifs and mottoes. This network served as a receptacle for the traditions of the European visual and literary arts. In its turn it Proceedings of the Emblem Project Utrecht Conference on influenced architecture, painting, love poetry, chil- dren’s books, preaching and interior decoration. Dutch Love Emblems and the Internet (November 2006) Together emblem books and the culture to which they belong form a web of closely interre- lated references. It is surely no coincidence that digitised emblem books are popular items on what may be their modern counterpart: the World Wide Web. In 2003 the Emblem Project Utrecht set out to digitise 25 representative Dutch love emblem books. The love emblem is one of the best known emblem- atic subgenres, first developed in the Low Countries and soon popular all over Europe. To celebrate the completion of the work done by the Emblem Project Utrecht, a conference was held on November 6 and 7, 2006. The focus of this con- ference was twofold: the Dutch love emblem and the process of digitising the emblems. This volume contains the selected papers of this conference, com- plemented by a general introduction and additional papers by the editors. Stronks and Boot DANS (Data Archiving and Networked Services) is the national organization in the Netherlands for storing and providing permanent access to research data from the humanities and social sciences. -

Dsm Magazine

CONTACT US SUBSCRIBE SUBMIT PHOTOS PAST ISSUES SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTIONS IA MAGAZINE ARTS DSM MAR/APR 2018 Lost and Found An unlikely investigation uncovers the naked truth behind a hidden treasure. ARTS Lost and Found ! " # 0 Showstoppers HOME ARTS DINING FASHION PEOPLE COMMUNITY NEWSLETTERS CALENDAR ! Facebook " Twitter # Pinterest Above: Skin, hair and fabric all share a fresh glow in this detail from a valuable artwork that languished in the shadows under centuries of darkened varnish and the grunge of time. Writer: Vicki L. Ingham Photographer: Duane Tinkey A dingy old painting pulled from a gloomy nook is about to experience a bright new life, with a new identity and a new value, enjoying it all from a perch on a wall at Hoyt Sherman Place. In many ways, the painting known as “Apollo and Venus” is a lottery winner in the art world, an instant celebrity plucked from obscurity by chance, destiny or mysterious intervention. Hoyt Sherman will unveil the restored painting March 21 at a special event (see details, page 146). As you may recall when we introduced the artwork in a previous dsm story, Hoyt Sherman’s executive director, Robert Warren, had been rummaging through a stash of old stuff, looking for Civil War flags, when he spotted some paintings tucked behind a table. One of them, a large, unsigned, oil-on-wood panel depicting a mythological scene, looked intriguing, he says, “so we pulled it out and put it on the table, thinking we’d go back to it.” Later, a member of the art and archives committee noticed it and texted Warren, saying, “I seem to recall that piece might be valuable.” As Warren wrapped the painting for protection, he noticed an auction tag on the back, identifying the work by name and attributing it to Italian artist Federico Barocci (1526-1612). -

The Leiden Collection

Emperor Commodus as Hercules ca. 1599–1600 and as a Gladiator oil on panel Peter Paul Rubens 65.5 x 54.4 cm Siegen 1577 – 1640 Antwerp PR-101 © 2017 The Leiden Collection Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator Page 2 of 11 How To Cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. "Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator." InThe Leiden Collection Catalogue. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017. https://www.theleidencollection.com/archive/. This page is available on the site's Archive. PDF of every version of this page is available on the Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. Archival copies will never be deleted. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2017 The Leiden Collection Emperor Commodus as Hercules and as a Gladiator Page 3 of 11 Peter Paul Rubens painted this bold, bust-length image of the eccentric Comparative Figures and tyrannical Roman emperor Commodus (161–92 A.D.) within an illusionistic marble oval relief. In stark contrast to his learned father Marcus Aurelius (121–80 A.D.), known as “the perfect Emperor,” Commodus, who reigned from 180 until he was murdered on New Year’s Eve of 192 at the age of 31, proudly distinguished himself by his great physical strength.[1] Toward the end of his life, Commodus went further than any of his megalomaniac predecessors, including Nero, and identified himself with Hercules, the superhumanly strong demigod of Greek mythology famous for slaughtering wild animals and monsters with his bare hands. According to the contemporary historian Herodian of Antioch (ca. -

Danaëandvenus and Adonis

AiA Art News-service Danaë and Venus and Adonis Danaë, Titian, 1551-1553. Oil on canvas, 192.5 cm x 114.6 cm. The Wellington Collection, Apsley House Venus and Adonis, Titian, 1554. Oil on canvas, 186 cm x 207 cm. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado The first "Poesie" presented to Prince Philip were Danaë(1553) and Venus and Adonis (1554), versions of other previous works, but endowed with all the prestige of the commissioning party. In turn, these works became models for numerous replicas. Danaë depicts the moment in which Jupiter possesses the princess in the form of golden rain. Titian painted his first Danaë in Rome in 1544-45 for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, in reference to the Cardinal's love affair with a courtesan. This Danaë was the model for the version created for Philip II, in which Cupid was replaced by an old nursemaid, whose inclusion enriched the painting by creating a series of sophisticated counterpoints: youth versus old age; beauty versus loyalty; a nude figure versus a dressed figure. Philip II received this work in 1553 and it was kept in the Spanish Royal Collection, first at the Alcázar and, subsequently, at the Buen Retiro Palace, until Ferdinand VII presented the work to the Duke of Wellington following the Peninsula War. Its original size was similar to that ofVenus and Adonis, but at the end of the 18th century, the upper third of the painting was removed for reasons of preservation. Historical descriptions and a Flemish copy reveal that the upper section included Jupiter's face and an eagle with bolts of lightning, both attributes of this particular god. -

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(S): W

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(s): W. R. Rearick Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 17, No. 33 (1996), pp. 23-67 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483551 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 17:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae. http://www.jstor.org W.R. REARICK Titian'sLater Mythologies I Worship of Venus (Madrid,Museo del Prado) in 1518-1519 when the great Assunta (Venice, Frari)was complete and in place. This Seen together, Titian's two major cycles of paintingsof mytho- was followed directlyby the Andrians (Madrid,Museo del Prado), logical subjects stand apart as one of the most significantand sem- and, after an interval, by the Bacchus and Ariadne (London, inal creations of the ItalianRenaissance. And yet, neither his earli- National Gallery) of 1522-1523.4 The sumptuous sensuality and er cycle nor the later series is without lingering problems that dynamic pictorial energy of these pictures dominated Bellini's continue to cloud their image as projected -

Abstracts of Amsterdam 2010 Conference Workshops

HNA in Amsterdam - "Crossing Boundaries" Workshop Summaries Rethinking Riegl Jane Carroll [email protected] Alison Stewart [email protected] In 1902, Alois Riegl wrote the Urquelle for all subsequent studies of Northern European group portraits, Das holländische Gruppenporträt. In that work, Riegl expanded art history beyond the contemporary emphasis on formalism and stylistic evolution. Drawing upon his interest in the relationship of objects within a work, Riegl asked his readers to expand that idea to include the viewer of art as an active participant in the understanding of visual works, an element he called “attentiveness.” In short, Riegl's book crossed the accepted boundary of what art history could consider and made viewing art a living exchange between present and past, and between viewer and object. Since its publication, all who have dealt with group portraiture have had to come into dialogue with Riegl’s book. In 1999, the Getty responded to a revived interest in Riegl's theories and republished The Group Portraiture of Holland in a new translation with historical introduction by Wolfgang Kemp. This reissuing increased the accessibility of Riegl’s work and reintroduced him to new generations of art historians. Prompted by that volume, we would like to gather together a group of scholars before the extensive collection of group portraits in the Amsterdams Historisch Museum. The venue of their Great Hall seems a perfect spot in which to reexamine the larger claims of Riegl’s work, and discuss current understandings of Dutch group portraiture. In keeping with the conference theme, we will explore how this genre crosses such boundaries as public vs. -

Titian, the Rape of Europa, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Titian, The Rape of Europa, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston Titian, Danaë, Wellington Collection, Apsley House, London The National Gallery’s much anticipated exhibition Titian – Love, Desire, Death opened on Monday, 16 March and I was lucky enough to see it the following day. It closed on the Wednesday of that week, together with the Gallery’s permanent collection, due to the Coronavirus crisis. A remarkable display, the most ravishing small-scale exhibition I have ever seen, the official closing date is 15 June, so if the Gallery reopens before then, please try to see it. The exhibition is due to continue at three of the other four art galleries whose generous loans have made this ground breaking art historical event possible: Edinburgh’s Scottish National Gallery, 11 July – 27 September; Madrid’s Prado Mueum, 20 October – 10 January; and Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 11 February – 9 May next year. So, should we not be able to feast our eyes on these spectacular works in London, we must hope for the opportunity elsewhere. The catalogue for the London, Edinburgh and Boston versions of the exhibition, also titled Titian – Love, Desire, Death is, given the closure of normal booksellers, widely available via Amazon or similar web suppliers: the ISBN number is 978 1 8570 9655 2 and costs £25. The Prado will publish a separate catalogue. As you may know, we have a Study Day in connection with the exhibition scheduled for 13 May and we very much hope that this may still be possible? Meanwhile, by way of anticipation I have written this short review of the exhibition, which I hope you will find of interest? 2 Titian, Venus and Adonis, Prado Museum, Madrid The exhibition represents a series of amazing ‘firsts’. -

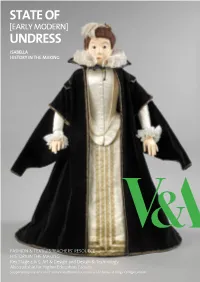

History in the Making – Isabella

ISABELLA HISTORY IN THE MAKING FASHION & TEXTILES TEACHERS’ RESOURCE HISTORY IN THE MAKING Key Stage 4 & 5: Art & Design and Design & Technology Also suitable for Higher Education Groups Supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council with thanks to Kings College London 1 FOREPART (PANEL) LIMEWOOD MANNEQUIN BODICE CHOPINES (SHOES) SLEEVE RUFFS GOWN NECK RUFF & REBATO HEADTIRE FARTHINGALE STOCKINGS & GARTERS WIG SMOCK 2 3 4 5 Contents Introduction: Early Modern Dress 9 Archduchess Isabella 11 Isabella undressing / dressing guide 12 Early Modern Materials 38 6 7 Introduction Early Modern Dress For men as well as women, movement was restricted in the Early Modern period, and as you’ll discover, required several The era of Early Modern dress spans between the 1500s to pairs of hands to put on. the 1800s. In different countries garments and tastes varied hugely and changed throughout the period. Despite this variation, there was a distinct style that is recognisable to us today and from which we can learn considerable amounts in terms of design, pattern cutting and construction techniques. Our focus is Europe, particularly Belgium, Spain, Austria and the Netherlands, where our characters Isabella and Albert lived or were connected to during their reign. This booklet includes a brief introduction to Isabella and Albert and a step-by-step guide to undressing and dressing them in order to gain an understanding of the detail and complexity of the garments, shoes and accessories during the period. The clothes you see would often be found in the Spanish courts, and although Isabella and Albert weren’t particularly the ‘trend-setters’ of their day, their garments are a great example of what was worn by the wealthy during the late 16th and early 17th centuries in Europe.