Stick Houses in Peshawbestown Matthew L.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warten Auf Das Neue Album

# 2018/01 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2018/01/warten-auf-das-neue-album In diesem Jahr erscheint das neue Album von The Breeders Warten auf das neue Album Von Dierk Saathoff Zehn Jahre sind vergangen, seit The Breeders ihr letztes Album veröffentlicht haben. Nun wurde ein neues für 2018 angekündigt. Die beiden Gitarre spielenden Frauen sahen sich zum Verwechseln ähnlich, auch ihre Singstimmen waren kaum voneinander zu unterscheiden. Der Moderator Conan O’Brien, in dessen Sendung dieser Auftritt 1993 stattfand, hatte die Band anhand ihrer Selbstbeschreibung angekündigt: »Just a bunch of rock chicks who like to play loud guitar music.« Und das taten die Breeders dann auch, vor einer Videoprojektion, die Menschen beim Billard zeigte, spielten sie laute Gitarrenmusik, genauer gesagt den Song »Divine Hammer«, wobei man nicht eindeutig klären kann, ob in dem Stück über einen gigantisch großen Penis oder doch über eine religiöse Erweckung gesungen wird. Über die Breeders wird durchgängig kolportiert, es handele sich bei ihnen um ein Nebenprojekt der Bassistin der Pixies, Kim Deal. Mit der Verwendung des Wortes »Nebenprojekt« geht eine Abwertung einher, eingefleischte Fans der Pixies reden sich so ein, die Mitglieder ihrer heiligen Band seien auf diese verpflichtet, wenn einer von ihnen noch in einer anderen Band involviert ist, sei das nur eine Spielerei, passiere nur nebenbei. Für Kim Deal war es wohl mehr als das: Genervt von den Attitüden des Sängers der Pixies, Frank Black, gründete sie 1989 wohl nicht zufällig eine fast ausschließlich aus Frauen bestehende Band, die Breeders. Auch Tanya Donelli und Josephine Wiggs hatten schon in anderen Bands gespielt und suchten bei den Breeders ein neues Umfeld, um besser das musikalisch verwirklichen zu können, was ihnen vorschwebte. -

Led Zeppelin R.E.M. Queen Feist the Cure Coldplay the Beatles The

Jay-Z and Linkin Park System of a Down Guano Apes Godsmack 30 Seconds to Mars My Chemical Romance From First to Last Disturbed Chevelle Ra Fall Out Boy Three Days Grace Sick Puppies Clawfinger 10 Years Seether Breaking Benjamin Hoobastank Lostprophets Funeral for a Friend Staind Trapt Clutch Papa Roach Sevendust Eddie Vedder Limp Bizkit Primus Gavin Rossdale Chris Cornell Soundgarden Blind Melon Linkin Park P.O.D. Thousand Foot Krutch The Afters Casting Crowns The Offspring Serj Tankian Steven Curtis Chapman Michael W. Smith Rage Against the Machine Evanescence Deftones Hawk Nelson Rebecca St. James Faith No More Skunk Anansie In Flames As I Lay Dying Bullet for My Valentine Incubus The Mars Volta Theory of a Deadman Hypocrisy Mr. Bungle The Dillinger Escape Plan Meshuggah Dark Tranquillity Opeth Red Hot Chili Peppers Ohio Players Beastie Boys Cypress Hill Dr. Dre The Haunted Bad Brains Dead Kennedys The Exploited Eminem Pearl Jam Minor Threat Snoop Dogg Makaveli Ja Rule Tool Porcupine Tree Riverside Satyricon Ulver Burzum Darkthrone Monty Python Foo Fighters Tenacious D Flight of the Conchords Amon Amarth Audioslave Raffi Dimmu Borgir Immortal Nickelback Puddle of Mudd Bloodhound Gang Emperor Gamma Ray Demons & Wizards Apocalyptica Velvet Revolver Manowar Slayer Megadeth Avantasia Metallica Paradise Lost Dream Theater Temple of the Dog Nightwish Cradle of Filth Edguy Ayreon Trans-Siberian Orchestra After Forever Edenbridge The Cramps Napalm Death Epica Kamelot Firewind At Vance Misfits Within Temptation The Gathering Danzig Sepultura Kreator -

Sun-Kissed Indie Rock with UM-Dearborn Roots

michiganjournal.org VOL. XLV, No. 10 THE STUDENT PUBLICATION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN-DEARBORN December 1, 2015 Sun-kissed Indie Rock With UM-Dearborn Roots Amber Ainsworth/MJ Go Tiger, Go!, a sun-kissed indie rock band, has University of Michigan-Dearborn roots through lead guitarist Paul Corsi, an alumn and former WUMD general manager. By AmBeR AINSwoRTh prefers ‘60s pop music and The Beatles, while still focusing A&E Editor on modern groups like Alabama Shakes and The Black Keys. It’s a Sunday evening and the usually streaming playlists Puz also enjoys ‘60s pop, but credits most of his inspiration on WUMD are suddenly interrupted by a playlist that hasn’t to his interest in ‘90s alternative, especially Soundgarden and echoed through the DJ booth in years. University of Michigan- Dearborn alum and former WUMD general manager Paul that he enjoys all music and takes “a little bit from hardcore, a Corsi and his band are on campus, relishing the early days of little bit from rap, a little bit from rock, punk.” Go Tiger, Go! in the room where it all began. If they had the option to collaborate with any musician, Puz would want to work with Chris Cornell because of the way laugh about how the room has changed over the years, and his music has evolved over the past 30 years, while Victor and reminisce while seated on a couch that Corsi credits himself Patten would like to make music with the multitalented Jack Paul Corsi Jon Victor as bringing into the WUMD room when he was still a student. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

7 1 @ = E = @ : 2 a > = AB

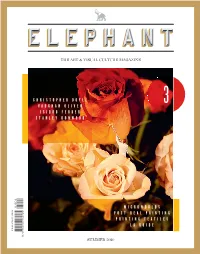

ELEPHANT / ISSUE 3 / SUMMER 2010 THE ART & VISUAL CULTURE MAGAZINE 16@7AB=>63@2=G:3 D / C 5 6 / < = : 7 D 3 @ 7A72@=43@@3@ AB/<:3G2=<E==2 ; 7 1 @ = E = @ : 2 A >=AB@3/:>/7<B7<5 >@7<B7<5B3FB7:3A :/5C723 £14.99, ¤19.95,£14.99, $19.99 BP BP SUMMER 2010 (BFRYHUB&RULQGG (BSB92OLYHULQGG B63 by Marc Valli ;7<=B/C@ 7< B63 :/0G@7<B6 D/C56/<Vaughan Oliver’s Extreme Regions =:7D3@Portrait by Giles Revell (BSB92OLYHULQGG ‘Fame requires every kind of excess. I mean true fame, a de- vouring neon… I mean danger, the edge of every void, the cir- cumstance of one man imparting an erotic terror to the dreams of the republic. Understand the man who must inhabit these ex- treme regions, monstrous and vulval, damp with memories of violation. Even if half-mad he is absorbed into the public’s to- tal madness: even if fully rational, a bureaucrat in hell, a secret genius of survival, he is sure to be destroyed by the public’s con- tempt for survivors… (Is it clear I was a hero of rock’n’roll?)’ — Don Delillo, ‘Great Jones Street’ It is diffi cult to think of Vaughan Oliver without making the aughan Oliver is mak- ing coffee with a digital radio playing in connection to music. His story seems to belong to the music the background. It is an unlikely setting: the clean and perfectly fitted kitchen of rather than the design world, following a path that’s closer to his tidy and tastefully decorated new that of a legend of rock’n’roll than a visual art one. -

History Report Freiburg HOT 30.07.2016 00 Through 05.08.2016 23

History Report Freiburg_HOT 30.07.2016 00 through 05.08.2016 23 Air Date Air Time Cat RunTime Artist Keyword Title Keyword Sa 30.07.2016 00:05 ARO 02:47 AnnenMayKantereit Wohin du gehst Sa 30.07.2016 00:08 SRO 04:17 BadBadNotGood Time Moves Slow (feat. Samuel T. Herring) Sa 30.07.2016 00:12 HIP 03:45 G Love and Special Sauce Baby's Got Sauce Sa 30.07.2016 00:16 J 00:12 uniFM ID Brothers Of Santa Claus Sa 30.07.2016 00:16 RCK 02:43 Beatsteaks Ain't Complaining Sa 30.07.2016 00:19 SRO 03:50 Hanna Georgas Don't Go Sa 30.07.2016 00:23 POP 02:38 Lambchop Gone Tomorrow Sa 30.07.2016 00:25 RCK 03:53 Funeral Suits All Those Friendly People Sa 30.07.2016 00:29 RCK 02:21 Kings of leon king of the rodeo Sa 30.07.2016 00:31 ARO 03:41 Gypsy and the Cat Inside Your Mind Sa 30.07.2016 00:35 POP 02:20 Fenster Oh Canyon Sa 30.07.2016 00:37 SRO 02:48 Charlie Cunningham Telling It Wrong Sa 30.07.2016 00:40 HIP 04:05 Der Tobi Und Das Bo Morgen geht die Bombe hoch Sa 30.07.2016 00:44 J 00:13 uniFM ID Wanda Sa 30.07.2016 00:45 SRO 02:45 Aesop Rock Kirby Sa 30.07.2016 00:47 ARO 03:54 Femme Dumb Blonde Sa 30.07.2016 00:51 EKR 03:29 Me Succeeds Riemerling Sa 30.07.2016 00:55 POP 02:46 Poor Moon People In Her Mind Sa 30.07.2016 00:57 POP 03:46 Coldplay Strawberry Swing Sa 30.07.2016 00:61 RCK 03:31 Say Hi to Your Mom northwestern girls Sa 30.07.2016 00:65 SRO 03:51 Oracles Amoeba Sa 30.07.2016 00:69 RCK 03:31 Kensington Road Tired Man Sa 30.07.2016 01:05 SRO 03:46 Joana Serrat Cloudy Heart Sa 30.07.2016 01:09 EKR 03:20 Caribou Our Love Sa 30.07.2016 01:12 HIP 04:22 -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/11/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/11/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Someone Like You - Adele Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Piano Man - Billy Joel At Last - Etta James Don't Stop Believing - Journey Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Wannabe - Spice Girls Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Jackson - Johnny Cash Free Fallin' - Tom Petty Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Look What You Made Me Do - Taylor Swift I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Body Like a Back Road - Sam Hunt Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Santeria - Sublime Summer Nights - Grease Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Turn The Page - Bob Seger Zombie - The Cranberries Crazy - Patsy Cline Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Kryptonite - 3 Doors Down My Girl - The Temptations Despacito (Remix) - Luis Fonsi Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Monster Mash - Bobby Boris Pickett Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's My Way - Frank Sinatra In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Rolling In The Deep - Adele All Of Me - John Legend These -

Progressive Music and Beyond a Discussion with Ivan Bertolla

Everything is Happy Underground by Ben Christie tracks, plus both sides of the hard-to-find all- following night, it looks as if we’ll be seeing more The sounds of Californian underground darlings instrumental 7” that came with initial copies of their of her in court (that is if she bothers to show up Grandaddy have been hovering around in our Isn’t Anything album. And all the tracks are lovingly and behave herself in the process) rather than on minds for the last few years, thanks in part to Triple remastered, so yeah, while it’s not quite new stage this year. J’s strong endorsement of them. But they’ve never material, it’s still very exciting news indeed. Well, the people of Detroit certainly got a surprise found the time to tour Australia – until now. They after Bob Dylan breezed through the last of three will arrive around May, and in the meantime get shows he did in the Motor City last month. yourself familiar with their gorgeous new album Sumday, which one critic described as sounding like a cross between Gram Parsons and the Alan Parsons Project(???). Someone who does have some belated new material in the can is PJ Harvey, who hasn’t put out anything new in nearly four years. On what Ahh, nothing like a little bit of Radiohead news will be her sixth studio album, Polly Jean handles to help us count down the days until they arrive most of the instrumental duties (with Rob Ellis on our golden soil. Thom Yorke’s middle finger helping out on percussion), and tackles the much appeared up for auction on eBay last month. -

Dossier De Premsa

22 – 26 MAYO BARCELONA DOSSIER DE PREMSA EL FESTIVAL CARTELL PARC DEL FÒRUM PROGRAMACIÓ COMPLEMENTÀRIA PRIMAVERA A LA CIUTAT PRIMAVERAPRO ORGANITZACIÓ I PARTNERS TICKETS CAMPANYA GRÀFICA CITES DE PREMSA HISTÒRIA CONTACTE ANNEX: BIOGRAFIES D’ARTISTES EL FESTIVAL Des dels seus inicis, el festival ha centrat els seus esforços en oferir noves propostes musicals de l’àmbit independent juntament amb artistes de contrastada trajectòria i de qualsevol estil o gènere, buscant primor- dialment la qualitat i apostant essencialment pel pop, el rock i les tendències més underground de la música electrònica i de ball. El festival ha comptat al llarg de la seva història amb propostes dels més diversos colors i estils. Així ho demostren els artistes que durant aquests deu anys han desfilat pels seus escenaris: de Pixies a Aphex Twin, passant per Neil Young, Sonic Youth, Portishead, Pet Shop Boys, Pavement, Echo & The Bunnymen, Lou Reed, My Bloody Valentine, El-P, Pulp, Patti Smith, James Blake, Arcade Fire, Cat Power, Public Enemy, Grin- derman, Franz Ferdinand, Television, Devo, Enrique Morente, The White Stripes, LCD Soundsystem, Tinders- ticks, PJ Harvey, Shellac, Dinosaur Jr., New Order, Surfin’ Bichos, Fuck Buttons, Swans, Melvins, The National, Psychic TV, Spiritualized, The Cure, Bon Iver, La Buena Vida, Death Cab For Cutie, Iggy & The Stooges, De La Soul, Marianne Faithfull o Mazzy Star, entre molts d’altres. Primavera Sound s’ha consolidat com el festival urbà per excel·lència amb característiques úniques, atès que es desmarca de la resta de macro esdeveniments musicals i es manté fidel a la línia artística, el nivell d’exigència i la qualitat organitzativa de les passades edicions, prescindint de grups de caràcter comercial. -

Arbiter, March 15 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 3-15-2004 Arbiter, March 15 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. I .\ L I' B 0 I S E ATE'S NDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER s ",. MONDAY CELEBRATING . MARCH 15; 2004 70 YEARS BSU speaks out Hawk and squad show aboul"Passion" their soft sides A&E-8 SPORTS· 5 FIRST COPY FREE , WWW.ARBITERONLINE ..COM VOLUME 16 ISSUE SO 11 j! . I 11 II : ! j, I.' l BYBETHANY MAILE News Reporter David Morriss and Tom Labrecque were announced ASBSU President and Vice President, Friday in the SUB's dining hall. Morriss and Labrecque took home 726 votes, leaving competitors Wolfe and Greene with 560 and Skaggs and Campbell with 394. Boise State experienced its largest voter turn out in 11 years, totaling 1,702 votes. Morriss said his first objective in office is to appoint a diverse cabinet. "I want representatives from all fields so .1 can feel the heart beat of Boise State stu- dents," Morriss said. Morriss also emphasized the importance of representation. "The whole point of stu- dent government is to give students a voice. -

Students Express Priorities at Forum Man Charged in Village Shootings

lE'W* i the Rice resher Vol. XCI, Issue No. 28 SINCE 1916 Friday, April 23, 2004 Students express priorities at forum by Risa Gordon Students at the forum brought WRKSHER i:i»rr<»KIAl STAFF up the importance of emphasizing research while also maintaining Teaching quality, building projects high-quality teaching. Brown Col- and student-governance were among lege Senator James Lloyd said the issues discussed by about 30 stu- class sizes are much larger than a dents at an SA forum held Monday. decade ago. citing CHEM 211/212: Student Association President Derrick Organic Chemistry, which has Matthews held the forum in lieu of 242 students enrolled this semester. the weekly SA meeting in order to "I don't know if it's a corollary decide what issues students found to the fact that in the past 10 years, important to convey to President-elect we've focused on building, but I've David Ixiebron. talked to alumni from 10 years ago Leebron will take office July 1, ... and they've noticed a decline in and Matthews, a Will Rice College undergraduate education." Lloyd, a junior, said he expects to meet with sophomore, said. • ,• v.: • - . Leebron over the summer to present Jones College Senator Kendall some of the ideas identified as most Smith said he agrees the quality important by forum participants. of undergraduate education is an The main topics Matthews said important issue. he will present are improving the "I think that the quality of teachers quality of teaching offered at Rice, needs to improve, because I agree MARSHALL ROBIN building a new recreation center and that people are unmotivated to go increasing the amount of on-campus to class just because some of the housing available to students. -

Jesse Reiter Attends Forum Looking at the Use Of

Jun15 6/14/06 3:05 PM Page 1 Thursday June 15, 2006 DAILY www.legalnews.com BRIEFING Vol. CXI No. 119 News you cannot get anywhere else 75 Cents Court announces HOWARD SOIFER MEMORIAL LECTURE appointments to grievance commission Inaugural sports, entertainment law lecture hosted The Michigan Supreme Court recently ROBERTA M. GUBBINS by Smith, the largest gift from a professional “In those days, not too many people citizens in their communities. made the following appointments and reap- Legal News athlete to his alma mater. thought of professional sports as a serious —Last, the globalization of sports. pointments to the Attorney Grievance Com- Steve Smith, an outstanding player for career. My father was the one who supported “I guess,” he added, “I have to include a mission (AGC): Steve Smith, National Basketball Associa- Michigan State University, turned pro at the my decision to go to the NBA. I was the only fifth area, the use of performance enhancing • Karen Quinlan Valvo of Ann Arbor, attorney tion All-Star, and Russ Granik, deputy com- age of 18. “At that time Howard became my lawyer. Now we have more than twenty drugs on sports. The game of basketball and shareholder in the law firm of Reach, Reach, missioner and chief operating officer of the lawyer. His favorites words were ‘go for it.’ lawyers on our staff who specialize in intellec- seems to have been spared involvement with Fink, & Valvo P.C. She is reappointed as chair for National Basketball Association, were the fea- He pushed me to become a better person.