Americans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1718Studyguidetosca.Pdf

TOSCA An opera in three acts by Giocomo Puccini Text by Giacosa and Illica after the play by Sardou Premiere on January 14, 1900, at the Teatro Constanzi, Rome OCTOBER 5 & 7, 2O17 Andrew Jackson Hall, TPAC The Patricia and Rodes Hart Production Directed by John Hoomes Conducted by Dean Williamson Featuring the Nashville Opera Orchestra CAST & CHARACTERS Floria Tosca, a celebrated singer Jennifer Rowley* Mario Cavaradossi, a painter John Pickle* Baron Scarpia, chief of police Weston Hurt* Cesare Angelotti, a political prisoner Jeffrey Williams† Sacristan/Jailer Rafael Porto* Sciarrone, a gendarme Mark Whatley† Spoletta, a police agent Thomas Leighton* * Nashville Opera debut † Former Mary Ragland Young Artist TICKETS & INFORMATION Contact Nashville Opera at 615.832.5242 or visit nashvilleopera.org. Study Guide Contributors Anna Young, Education Director Cara Schneider, Creative Director THE STORY SETTING: Rome, 1800 ACT I - The church of Sant’Andrea della Valle quickly helps to conceal Angelotti once more. Tosca is immediately suspicious and accuses Cavaradossi of A political prisoner, Cesare Angelotti, has just escaped and being unfaithful, having heard a conversation cease as she seeks refuge in the church, Sant’Andrea della Valle. His sis - entered. After seeing the portrait, she notices the similari - ter, the Marchesa Attavanti, has often prayed for his release ties between the depiction of Mary Magdalene and the in the very same chapel. During these visits, she has been blonde hair and blue eyes of the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca, observed by Mario Cavaradossi, the painter. Cavaradossi who is often unreasonably jealous, feels her fears are con - has been working on a portrait of Mary Magdalene and the firmed at the sight of the painting. -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

FINAL Tosca 2018

Stories Told Through Singing TOSCA Giacomo Puccini OPERA: Stories Told Through Singing At Palm Beach Opera, we believe that opera tells stories to which we can all relate, and that is why the operatic art form has thrived for centuries. The education programs at Palm Beach Opera plug the community directly into those stories, revealing timeless tales of love, passion, and joy. We challenge each person to find their own connection to opera’s stories, inspiring learners of all ages to explore the world of opera. At Palm Beach Opera there is something for everyone! #PBOperaForAll 1 PBOPERA.ORG // 561.833.7888 TOSCA Giacomo Puccini The Masterminds pg 3 Who's Who pg 7 Understanding the Action pg 9 Engage Your Mind pg 13 PBOPERA.ORG // 561.833.7888 2 The Masterminds 3 PBOPERA.ORG // 561.833.7888 Giacomo Puccini Composer Giacomo Puccini (December 22, 1858 – November 29, 1924) was born into a musical family. He studied composition at the Milan Conservatory, writing his first opera in 1884 at the age of 26. A prolific composer, Puccini wrote many operas including several that are still in performance today: Manon Lescaut, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, La fanciulla del West, La rondine, Suor Angelica, Gianni Schicchi, Turandot, and La bohème. Although the designation of Puccini as a verismo composer is debated, many of his works can fit in this category. Verismo is derived from the Italian word ‘vero’ meaning'true;' the style is distinguished by realistic lines and genuine characters. Fun Factoid: Puccini's full name was Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini. -

(“You Love Opera: We'll Go Twice a Week”), Des Grieux Promise

MANON AT THE OPERA: FROM PRÉVOST’S MANON LESCAUT TO AUBER’S MANON LESCAUT AND MASSENET’S MANON VINCENT GIROUD “Vous aimez l’Opéra: nous irons deux fois la semaine” (“You love opera: we’ll go twice a week”), Des Grieux promises Manon in Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, as the lovers make plans for their life at Chaillot following their first reconciliation.1 Opera, in turn, has loved Manon, since there exist at least eight operatic versions of the Abbé Prévost’s masterpiece – a record for a modern classic.2 Quickly written in late 1730 and early 1731, the Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut first appeared in Amsterdam as Volume VII of Prévost’s long novel Mémoires d’un homme de qualité.3 An instantaneous success, it went 1 Abbé Prévost, Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, ed. Frédéric Deloffre and Raymond Picard, Paris: Garnier frères, 1965, 49-50. 2 They are, in chronological order: La courtisane vertueuse, comédie mȇlée d’ariettes four Acts (1772), libretto attributed to César Ribié (1755?-1830?), music from various sources; William Michael Balfe, The Maid of Artois, grand opera in three Acts (1836), libretto by Alfred Bunn; Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Manon Lescaut, opéra comique in three Acts (1856), libretto by Eugène Scribe; Richard Kleinmichel, Manon, oder das Schloss de l’Orme, romantic-comic opera in four Acts (1887), libretto by Elise Levi; Jules Massenet, Manon, opéra comique in five Acts and six tableaux (1884), libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe Gille; Giacomo Puccini, Manon Lescaut, lyrical drama in four Acts (1893), libretto by Domenico Oliva, Giulio Ricordi, Luigi Illica, Giuseppe Giacosa, and Marco Praga; and Hans Werner Henze, Boulevard Solitude, lyric drama in seven Scenes (1951), libretto by Grete Weil on a scenario by Walter Jockisch. -

Giuseppe Giacosa

Percorso I generi 4. Il dramma borghese e il teatro verista e dialettale in Italia Giuseppe La vita Nato nel 1847 a Colleretto Parella (Ivrea), Giacosa si laureò in giurisprudenza ed eser- Giacosa citò la professione di avvocato nello studio legale paterno, prima di dedicarsi all’attività teatrale. Trasferitosi a Milano, frequentò gli ambienti della Scapigliatura, si avvicinò al Verismo e fu direttore all’Accademia di recitazione fi lodrammatica. Morì nel 1906. Le opere e i temi Le prime opere teatrali in versi Una partita a scacchi (1873) e Il Conte Rosso (1880) sono di ambientazione medioevale e di gusto tardoromantico. Sensibile alla lezione del Verismo e del Naturalismo francese (Zola, Becque), passò ad argomenti contem- poranei nei suoi drammi più signifi cativi: Tristi amori (1887), recitato da Eleonora Duse; La signora di Challant (1891), portato con successo sulle scene a New York da Sarah Bernhardt; I diritti dell’anima (1894) infl uenzato da lbsen; Come le foglie (1900; Il confl itto familiare, ), vicino alle grigie atmosfere di Cˇechov. Le tecniche drammaturgiche di Giacosa rifuggono dall’eff etto scenico e si affi dano alla capacità di esprimere il dramma anche attraverso le suggestioni del sottinteso, del non detto, mentre balzano in primo piano la quotidianità della vita borghese, i problemi fami- liari, il tema del denaro come forza motrice e disgregatrice della società borghese. Giacosa collaborò anche con Luigi Illica ai libretti di alcune opere di Puccini (La Bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfl y). LA TRAMA Come le foglie Il banchiere Giovanni Rosani, in seguito a un tracollo economico di cui non è responsabile, è costretto a trasferirsi da un sontuoso palazzo di Milano in una modesta casa in Svizzera. -

Madama Butterfly

A Letter to the Teachers Dear Teachers, 1 A Letter to the Teachers Opera Colorado is pleased to continue providing engaging and educational programs and performances for students across Colorado. What follows is a guide that we hope you find useful as you, and your students, learn about and explore Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. In the spirit of exploration, we have included a set of 45 minute lessons that connects the opera with all different subjects of learning: music, visual arts, language arts, social studies, math, and science. The lessons include reference to, and are based upon, the new Colorado Department of Education’s Academic Standards: specifically, focusing on the fourth grade expectations. This does not mean, however, that these lessons should be limited to this age group. While we would be very pleased if you used these lessons in the exact format provided, we encourage you to expand, alter, and adapt these lessons so that they best fit your students’ abilities and development. After all, the teacher knows their student’s needs best. We would appreciate your feedback on our teacher evaluation form found at the end of this guide, and we hope that you enjoy all that Opera Colorado has to offer! Ciao! - Cherity Koepke - Director of Education & Community Engagement - Elena Kalahar - Education Intern - Alexandra Kotis - Education Intern 2 Contact us to learn more! Opera Colorado’s Education & Community Engagement department offers many more programs to assist your students as they continue to discover the world of opera. We have programs that take place at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House as well as programs that we can bring directly to your classroom. -

SOCIAL STUDIES: Historical Settings for Opera/ Becoming the Librettist

SOCIAL STUDIES: Historical Settings for Opera/ Becoming the Librettist Students will Read for information and answer questions Research an event, civilization, landmark, or literary work as a source for a setting Write a brief setting and story as the basis for an opera Copies for Each Student: Tosca Synopsis, “What is a Librettist”, “Our Librettists, Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica“, Activity Worksheet Copies for the Teacher: Social Studies lesson plan, Tosca Synopsis, “What is a Librettist”, “Our Librettists, Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica“, Activity Worksheet, Answer Key Getting Ready Prepare internet access for possible research for guided practice or group work. Gather pens, pencils and additional writing paper as needed for your students. Introduction Explain to your students that a commissioned work is a piece of visual or performing art created at the request and expense of someone else. Begin the lesson by explaining to your students that composers and librettists work closely to create an opera. Have the students discuss what they believe the research duties of a librettist are. You may want to guide the discussion so that the students begin to understand the historic and cultural influence on opera and art as a whole. Have your students read the synopsis, “What is a Librettist”, and “Our Librettists, Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica”. Give each student a copy of the Activity Worksheet or display it on a screen. Give an overview of the assignment, and point out the information your students are expected to research and write about. To align with Texas TEKS, you may provide and tailor research topics according to your grade level: 6th Grade: Societies of the contemporary world. -

Bob & Phyllis Neumann

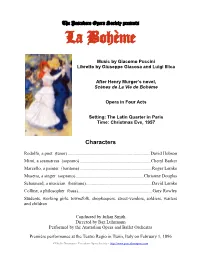

The Pescadero Opera Society presents La Bohème Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica After Henry Murger’s novel, Scènes de La Vie de Bohème Opera in Four Acts Setting: The Latin Quarter in Paris Time: Christmas Eve, 1957 Characters Rodolfo, a poet (tenor) ........................................................................ David Hobson Mimì, a seamstress (soprano) .............................................................. Cheryl Barker Marcello, a painter (baritone) ............................................................... Roger Lemke Musetta, a singer (soprano) ............................................................Christine Douglas Schaunard, a musician (baritone) .......................................................... David Lemke Colline, a philosopher (bass) ................................................................. Gary Rowley Students, working girls, townsfolk, shopkeepers, street-vendors, soldiers, waiters and children Conducted by Julian Smith Directed by Baz Luhrmann Performed by the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra Première performance at the Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy on February 1, 1896 ©Phyllis Neumann • Pescadero Opera Society • http://www.pescaderoopera.com 2 Synopsis Act I A garret in the Latin Quarter of Paris on Christmas Eve, 1957 The near-destitute artist, Marcello and poet Rodolfo try to keep warm on Christmas Eve by feeding the stove with pages from Rodolfo’s latest drama. They are soon joined by their roommates, Colline, a young philosopher, and Schaunard, a musician who has landed a job bringing them all food, fuel and money. While they celebrate their unexpected fortune, the landlord, Benoit, arrives to collect the rent. Plying the older man with wine, the Bohemians urge him to tell of his flirtations, then throw him out in mock indignation at his infidelity to his wife. Schaunard proposes that they celebrate the holiday at the Café Momus. Rodolfo remains behind to try to finish an article, promising to join them later. -

WNO Boheme Sim REORDER2 Print Spreads

WASHINGTON NATIONAL OPERA ORCHESTRA HEINZ FRICKE, MUSIC DIRECTOR Violin I Cello Clarinet Bass Trombone Oleg Rylatko, Amy Frost Baumgarten, David Jones, Principal Stephen Dunkel Concertmaster Principal Lora Ferguson, Assistant Eric Lee, Associate Elizabeth Davis,Assistant Principal Tuba/Cimbasso Concertmaster Principal Stephen Bates Michael Bunn, Principal Zino Bogachek+** Ignacio Alcover+ Joan Cataldo Amy Ward Butler Bass Clarinet Timpani Michelle Kim Timothy H. Butler** Stephen Bates Jonathan Rance, Principal Karen Lowry-Tucker Igor Zubkovsky Greg Akagi, Assistant Susan Midkiff Kerry Van Laanen* Bassoon Principal Washington National Opera’s Board of Trustees Margaret Thomas Donald Shore, Principal Charlie Whitten Bass Christopher Jewell, Percussion presents Doug Dube* Robert D’Imperio, Assistant Principal John Spirtas, Principal Jennifer Himes* Principal Nancy Stutsman Greg Akagi Patty Hurd* Frank Carnovale, Assistant Bill Richards* A Live Broadcast from Agnieszka Kowalsky* Principal Contrabassoon John Ricketts Nancy Stutsman Harp The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Violin II Jeffrey Koczela* Susan Robinson, Principal Julia Grueninger, Horn Sunday, September 23, 2007 Principal Flute Gregory Drone, Principal ADMINISTRATION Joel Fuller, Assistant Adria Sternstein Foster, John Peiffer, Assistant Principal Principal Principal Orchestra Personnel & Richard Chang+ Stephani Stang-Mc- Robert Odmark Operations Manager Xi Chen Cusker, Assistant Peter de Boor Aaron Doty Jessica Dan Fan Principal Geoffrey Pilkington Martha Kaufman -

La Bohème Was Made Possible by a Generous Gift from Mrs

laGIACOMO PUCCINI bohème conductor Opera in four acts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Franco Zeffirelli Luigi Illica, based on the novel Scènes de la Vie de Bohème by Henri Murger set designer Franco Zeffirelli Tuesday, November 29, 2016 costume designer 7:30–10:30 PM Peter J. Hall lighting designer Gil Wechsler revival stage director J. Knighten Smit The production of La Bohème was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. Donald D. Harrington The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from the Metropolitan Opera Club general manager Peter Gelb music director emeritus James Levine principal conductor Fabio Luisi 2016–17 SEASON The 1,300th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S la bohème conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance marcello muset ta Massimo Cavalletti Brigitta Kele rodolfo customhouse serge ant Piotr Beczała Yohan Yi colline customhouse officer Ryan Speedo Green* Joseph Turi schaunard Patrick Carfizzi benoit Paul Plishka mimì Kristine Opolais parpignol Daniel Clark Smith alcindoro Paul Plishka Tuesday, November 29, 2016, 7:30–10:30PM MARTY SOHL/METROPOLITAN OPERA MARTYSOHL/METROPOLITAN A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Puccini’s La Bohème Musical Preparation Howard Watkins, J. David Jackson, Thomas Bagwell, and Joshua Greene Assistant Stage Director Gregory Keller Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Joshua Greene Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Associate Designer David Reppa Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ladies millinery by Reggie G. -

Pathways for Understanding; La Boheme

2 Table of Contents An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials 3 Production Information/Meet the Characters 4 The Story of La Bohème 5 The History of Puccini’s La Bohème 7 Guided Listening Che gelida manina! 10 Sì. Mi chiamano Mimì 11 O soave fanciulla 12 Quando me'n vo' 13 Donde lieta uscì 14 O Mimì, tu più non torni 15 Vecchia zimarra, senti 16 La Bohème Resources About the Composer 17 Puccini, Verismo, and La Bohème 20 Online Resources 23 Additional Resources The Emergence of Opera 24 Metropolitan Opera Facts 28 Reflections after the Opera 30 A Guide to Voice Parts and Families of the Orchestra 31 Glossary 32 References Works Consulted 36 2 An Introduction to Pathways for Understanding Study Materials The goal of Pathways for Understanding materials is to provide multiple “pathways” for learning about a specific opera as well as the operatic art form, and to allow teachers to create lessons that work best for their particular teaching style, subject area, and class of students. Meet the Characters / The Story/ Resources Fostering familiarity with specific operas as well as the operatic art form, these sections describe characters and story, and provide historical context. Guiding questions are included to suggest connections to other subject areas, encourage higher-order thinking, and promote a broader understanding of the opera and its potential significance to other areas of learning. Guided Listening The Guided Listening section highlights key musical moments from the opera and provides areas of focus for listening to each musical excerpt. Main topics and questions are introduced, giving teachers of all musical backgrounds (or none at all) the means to discuss the music of the opera with their students. -

Puccini Operas and Revisions

GIACOMO PUCCINI LIST OF OPERAS AND REVISIONS • Le Villi, libretto by Ferdinando Fontana (in one act – premiered at the Teatro Dal Verme, 31 May 1884) o second version (in two acts – premiered at the Teatro Regio, 26 December 1884) o third version (in two acts – premiered at the Teatro alla Scala, 24 January 1885) o fourth version (in two acts – premiered at the Teatro dal Verme, 7 November 1889) • Edgar, libretto by Ferdinando Fontana (in four acts – premiered at the Teatro alla Scala, 21 April 1889) o second version (in four acts – premiered at the Teatro del Giglio, 5 September 1891) o third version (in three acts – premiered at the Teatro Comunale, 28 January 1892) o fourth version (in three acts – premiered at the Teatro Colón di Buenos Aires, 8 July 1905) • Manon Lescaut, libretto by Luigi Illica, Marco Praga and Domenico Oliva (in four acts – premiered at the Teatro Regio, 1 February 1893) o second version (premiered at the Teatro Coccia, 21 December 1893) • La bohème, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa (in four acts – premiered at the Teatro Regio, 1 February 1896) • Tosca, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa (in three acts – premiered at the Teatro Costanzi, 14 January 1900) • Madama Butterfly, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa (in two acts – premiered at the Teatro alla Scala, 17 February 1904) o second version (premiered at the Teatro Grande di Brescia, 28 May 1904) o third version (premiered at Covent Garden, London 10 July 1905) o fourth version (premiered at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, 28