Shifting: the Creation and Theoretical Exploration of a Collaborative Autobiographical Novel Helen Cerne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EECE 1070 Curve Fitting and Data Analysis

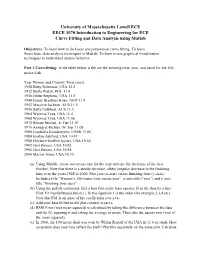

University of Massachusetts Lowell ECE EECE 1070 Introduction to Engineering for ECE Curve Fitting and Data Analysis using Matlab Objectives: To learn how to do linear and polynomial curve fitting. To learn Some basic data analysis techniques in Matlab; To learn to use graphical visualization techniques to understand system behavior. Part 1 Curvefitting: In the table below is the are the winning time, year, and name for the 100- meter dash. Year Winner and Country Time (secs) 1928 Betty Robinson, USA 12.2 1932 Stella Walsh, POL 11.9 1936 Helen Stephens, USA 11.5 1948 Fanny Blankers-Koen, NED 11.9 1952 Marjorie Jackson, AUS 11.5 1956 Betty Cuthbert, AUS 11.5 1964 Wyomia Tyus, USA 11.4 1968 Wyomia Tyus, USA 11.08 1972 Renate Stecher, E. Ger 11.07 1976 Annegret Richter, W. Ger 11.08 1980 Lyudmila Kondratyeva, USSR 11.06 1984 Evelyn Ashford, USA 10.97 1988 Florence Griffith Joyner, USA 10.54 1992 Gail Devers, USA 10.82 1996 Gail Devers, USA 10.94 2000 Marion Jones, USA 10.75 (a) Using Matlab, create two arrays one for the year and one for the times of the best finisher. Note that there is a steady decrease, albeit irregular decrease in the finishing time over the years 1928 to 2000. Plot year (x-axis) versus finishing time (y-axis). Include a title “Women’s 100-meter time versus year”, x-axis title (“year”) and y’axis title “finishing time (sec)” (b) Using the polyfit command, find a best first order least squares fit to the data by a line: Hint: Fit1=polyfit(year,finish,1). -

0 Eulogy Delivered by Alan Jones Ao Honouring the Life

EULOGY DELIVERED BY ALAN JONES AO HONOURING THE LIFE OF BETTY CUTHBERT AM MBE AT THE SYDNEY CRICKET GROUND MONDAY 21 AUGUST 2017 0 There is a crushing reminder of our own mortality in being here today to honour and remember the unyieldingly great Betty Cuthbert, AM. MBE. Four Olympic gold medals, one Commonwealth Games gold medal, two silver medals, 16 world records. The 1964 Helms World Trophy for Outstanding Athlete of the Year in all amateur sports in Australia. And it’s entirely appropriate that this formal and official farewell, sponsored by the State Government of New South Wales, should be taking place in this sporting theatre, which Betty adorned and indeed astonished in equal measure. It was here that in preparation for the Cardiff Empire Games in 1958 and the Rome Olympics in 1960, as the Games were being held in the Northern Hemisphere, out of season for Australian athletes, that winter competition was arranged to bring them to their peak. Races were put on here at the Sydney Cricket Ground at half time during a rugby league game. And it was in July 1978, as Betty was suffering significantly, but not publicly, from multiple sclerosis, that the government of New South Wales invited Betty Cuthbert to become the first woman member of the Sydney Cricket Ground Trust. Of course, in the years since that appointment, as Betty herself acknowledged, her road became often rocky and steep. 1 She once talked about the pitfalls, the craters and the hurdles. But along the way, she found many revival points. -

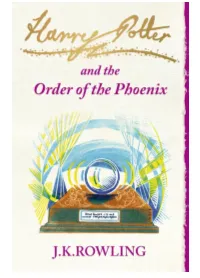

HARRY POTTER and the Order of the Phoenix

HARRY POTTER and the Order of the Phoenix J.K. ROWLING All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher This digital edition first published by Pottermore Limited in 2012 First published in print in Great Britain in 2003 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Copyright © J.K. Rowling 2003 Cover illustrations by Claire Melinsky copyright © J.K. Rowling 2010 Harry Potter characters, names and related indicia are trademarks of and © Warner Bros. Ent. The moral right of the author has been asserted A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-78110-011-0 www.pottermore.com by J.K. Rowling The unique online experience built around the Harry Potter books. Share and participate in the stories, showcase your own Potter-related creativity and discover even more about the world of Harry Potter from the author herself. Visit pottermore.com To Neil, Jessica and David, who make my world magical CONTENTS ONE Dudley Demented TWO A Peck of Owls THREE The Advance Guard FOUR Number Twelve, Grimmauld Place FIVE The Order of the Phoenix SIX The Noble and Most Ancient House of Black SEVEN The Ministry of Magic EIGHT The Hearing NINE The Woes of Mrs Weasley TEN Luna Lovegood ELEVEN The Sorting Hat’s New Song TWELVE Professor Umbridge THIRTEEN Detention with Dolores FOURTEEN Percy and Padfoot FIFTEEN The Hogwarts High Inquisitor SIXTEEN In the Hog’s Head SEVENTEEN Educational Decree Number -

Known Nursery Rhymes Residencies Fruit Eaten Remembered World

13 Nov. 1995 – Leah Betts in coma after taking ecstasy 26 Sep. 2007 – Myanmar government, using extreme force, cracks down on protests Blockbusters Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1982 Pratchett, T. – Soul Music Celery Hilden, Linda The Tortoise and the Eagle Beverly Hills Cop Goodfellas Speed Peanut Brittle Dial M for Murder Russ Abbott Arena Coast To Coast Gary Numan Live Rammstein Vast Ready to Rumble (Dreamcast) Known Nursery Rhymes 22 Nov. 1995 – Rosemary West sentenced to life imprisonment 06 Oct. 2007 – Musharraf breezes to easy re-election in Pakistan Buckaroo Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1984 Pratchett, T. - Sorcery Chard Hill, Debbie The Jackdaw and the Fox Beverly Hills Cop 2 The Goonies Speed 2 Pear Drops Dinnerladies The Ruth Rendell Mysteries Aretha Franklin Cochine Gene McDaniels The Living End Ramones Vegastones Resident Evil (Various) All Around the Mulberry Bush 14 Dec. 1995 – Bosnia peace accord 05 Nov. 2007 – Thousands of lawyers take to the streets to protest the state of emergency rule in Pakistan. Chess Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1985 Pratchett, T. – The Streets of Ankh-Morpork Chickpea Hiscock, Anna-Marie The Boy and the Wolf Bicentennial Man The Good, The Bad and the Ugly Spider Man Picnic Doctor Who The Saint Armand Van Helden Cockney Rebel Gene Pitney Lizzy Mercier Descloux Randy Crawford The Velvet Underground Robocop (Commodore 64) As I Was Going to St. Ives 02 Jan. 1996 – US Peacekeepers enter Bosnia 09 Nov. 2007 – Police barricade the city of Rawalpindi where opposition leader Benazir Bhutto plans a protest Chinese Checkers Bestall, A. – Rupert Annual 1988 Pratchett, T. -

Detailed List of Performances in the Six Selected Events

Detailed list of performances in the six selected events 100 metres women 100 metres men 400 metres women 400 metres men Result Result Result Result Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country Year Athlete Country (sec) (sec) (sec) (sec) 1928 Elizabeth Robinson USA 12.2 1896 Tom Burke USA 12.0 1964 Betty Cuthbert AUS 52.0 1896 Tom Burke USA 54.2 Stanislawa 1900 Frank Jarvis USA 11.0 1968 Colette Besson FRA 52.0 1900 Maxey Long USA 49.4 1932 POL 11.9 Walasiewicz 1904 Archie Hahn USA 11.0 1972 Monika Zehrt GDR 51.08 1904 Harry Hillman USA 49.2 1936 Helen Stephens USA 11.5 1906 Archie Hahn USA 11.2 1976 Irena Szewinska POL 49.29 1908 Wyndham Halswelle GBR 50.0 Fanny Blankers- 1908 Reggie Walker SAF 10.8 1980 Marita Koch GDR 48.88 1912 Charles Reidpath USA 48.2 1948 NED 11.9 Koen 1912 Ralph Craig USA 10.8 Valerie Brisco- 1920 Bevil Rudd SAF 49.6 1984 USA 48.83 1952 Marjorie Jackson AUS 11.5 Hooks 1920 Charles Paddock USA 10.8 1924 Eric Liddell GBR 47.6 1956 Betty Cuthbert AUS 11.5 1988 Olga Bryzgina URS 48.65 1924 Harold Abrahams GBR 10.6 1928 Raymond Barbuti USA 47.8 1960 Wilma Rudolph USA 11.0 1992 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.83 1928 Percy Williams CAN 10.8 1932 Bill Carr USA 46.2 1964 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.4 1996 Marie-José Pérec FRA 48.25 1932 Eddie Tolan USA 10.3 1936 Archie Williams USA 46.5 1968 Wyomia Tyus USA 11.0 2000 Cathy Freeman AUS 49.11 1936 Jesse Owens USA 10.3 1948 Arthur Wint JAM 46.2 1972 Renate Stecher GDR 11.07 Tonique Williams- 1948 Harrison Dillard USA 10.3 1952 George Rhoden JAM 45.9 2004 BAH 49.41 1976 -

Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2Nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 083 PS 027 309 AUTHOR Clarke, Genevieve, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998). INSTITUTION Children's Film and Television Foundation, Herts (England). PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 127p. AVAILABLE FROM Children's Film and Television Foundation, Elstree Studios, Borehamwood, Herts WD6 1JG, United Kingdom; Tel: 44(0)181-953-0844; e-mail: [email protected] PUB TYPE Collected Works - Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; *Childrens Television; Computer Uses in Education; Foreign Countries; Mass Media Role; *Mass Media Use; *Programming (Broadcast); *Television; *Television Viewing ABSTRACT This report summarizes the presentations and events of the Second World Summit on Television for Children, to which over 180 speakers from 50 countries contributed, with additional delegates speaking in conference sessions and social events. The report includes the following sections:(1) production, including presentations on the child audience, family programs, the preschool audience, children's television role in human rights education, teen programs, and television by kids;(2) politics, including sessions on the v-chip in the United States, the political context for children's television, news, schools television, the use of research, boundaries of children's television, and minority-language television; (3) finance, focusing on children's television as a business;(4) new media, including presentations on computers, interactivity, the Internet, globalization, and multimedia bedrooms; and (5) the future, focusing on anticipation of events by the time of the next World Summit in 2001 and summarizing impressions from the current summit. -

A Different Dog

A Different Dog By Paul Jennings May 2017 ISBN 9781760296469 paperback Recommended for readers aged 10-14 years. Summary Paul Jennings’ fans will be familiar with A Different Dog’s protagonist – the troubled young loner – and know that when it comes to creating such characters Jennings is without parallel. The boy in this story can’t speak to others, although he speaks to himself and animals when no one is around. No reason is given but we assume his problem is due to a disability or a reaction to a trauma in his past. Whatever the cause, he is teased mercilessly by other kids. The story opens with the boy setting out to compete in a fun run taking place on a cold, wintery day. Conditions are bleak and when hail sets in they become thoroughly dangerous. As he cautiously makes his way up a winding mountain road the boy is passed by a car with a dog sitting in the front passenger seat. Minutes later he hears the car’s brakes lock and realises that it has plunged over a guard rail to the mountain forest floor far below. Clambering to the wreckage the boy discovers that the driver has been killed and the dog thrown from the vehicle uninjured…but acting very strangely. The boy and dog set out on a perilous journey through difficult terrain and across a rickety old bridge. Along the way they come across a group of cruel teenagers and discover a bond that helps them beat the bullies and find their way home. -

The Olympic 100M Sprint

Exploring the winning data: the Olympic 100 m sprint Performances in athletic events have steadily improved since the Olympics first started in 1896. Chemists have contributed to these improvements in a number of ways. For example, the design of improved materials for clothing and equipment; devising and monitoring the best methods for training for particular sports and gaining a better understanding of how energy is released from our food so ensure that athletes get the best diet. Figure 1 Image of a gold medallist in the Olympic 100 m sprint. Year Winner (Men) Time (s) Winner (Women) Time (s) 1896 Thomas Burke (USA) 12.0 1900 Francis Jarvis (USA) 11.0 1904 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.0 1906 Archie Hahn (USA) 11.2 1908 Reginald Walker (S Africa) 10.8 1912 Ralph Craig (USA) 10.8 1920 Charles Paddock (USA) 10.8 1924 Harold Abrahams (GB) 10.6 1928 Percy Williams (Canada) 10.8 Elizabeth Robinson (USA) 12.2 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA) 10.38 Stanislawa Walasiewick (POL) 11.9 1936 Jessie Owens (USA) 10.30 Helen Stephens (USA) 11.5 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA) 10.30 Fanny Blankers-Koen (NED) 11.9 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA) 10.78 Majorie Jackson (USA) 11.5 1956 Bobby Morrow (USA) 10.62 Betty Cuthbert (AUS) 11.4 1960 Armin Hary (FRG) 10.32 Wilma Rudolph (USA) 11.3 1964 Robert Hayes (USA) 10.06 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.2 1968 James Hines (USA) 9.95 Wyomia Tyus (USA) 11.08 1972 Valeriy Borzov (USSR) 10.14 Renate Stecher (GDR) 11.07 1976 Hasely Crawford (Trinidad) 10.06 Anneqret Richter (FRG) 11.01 1980 Allan Wells (GB) 10.25 Lyudmila Kondratyeva (USA) 11.06 1984 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.99 Evelyn Ashford (USA) 10.97 1988 Carl Lewis (USA) 9.92 Florence Griffith-Joyner (USA) 10.62 1992 Linford Christie (GB) 9.96 Gail Devers (USA) 10.82 1996 Donovan Bailey (Canada) 9.84 Gail Devers (USA) 10.94 2000 Maurice Green (USA) 9.87 Eksterine Thanou (GRE) 11.12 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA) 9.85 Yuliya Nesterenko (BLR) 10.93 2008 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.69 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.78 2012 Usain Bolt (Jam) 9.63 Shelly-Ann Fraser (Jam) 10.75 Exploring the wining data: 100 m sprint| 11-16 Questions 1. -

World Rankings — Women's

World Rankings — Women’s 100 © GIANCARLO COLOMBO/PHOTO RUN The ’08 Olympic gold led to the first of Shelly-Ann Fraser- Pryce’s 5 No. 1s in a 12-year span 1956 1957 1 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 1 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 2 ........ Christa Stubnick (East Germany) 2 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 3 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 3 ...............Vera Krepkina (Soviet Union) 4 ..............Galina Popova (Soviet Union) 4 ...........Hannie Bloemhof (Netherlands) 5 .............................Isabelle Daniels (US) 5 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 6 ...................... Giuseppina Leone (Italy) 6 ..............Galina Popova (Soviet Union) 7 ..... Gisela Birkemeyer (East Germany) 7 .......................... Erica Willis (Australia) 8 ......................June Paul (Great Britain) 8 .....Brunhilde Hendrix (West Germany) 9 ..............Heather Young (Great Britain) 9 .........................Fleur Mellor (Australia) 10 ..... Galina Rezchikova (Soviet Union) 10 ..........Madeleine Cobb (Great Britain) © Track & Field News 2020 — 1 — World Rankings — Women’s 100 1958 1962 1 ...................Marlene Willard (Australia) 1 ............ Dorothy Hyman (Great Britain) 2 .................... Betty Cuthbert (Australia) 2 ..............................Wilma Rudolph (US) 3 ...............................Barbara Jones (US) 3 ................ Jutta Heine (West Germany) 4 ..............Heather Young (Great Britain) 4 ..........................Teresa Ciepła (Poland) 5 -

Skydragon: Skydragon 1 Anh Do, Illustrated by James Hart

AUSTRALIA OCTOBER 2020 Skydragon: Skydragon 1 Anh Do, illustrated by James Hart Amazing new adventure series from mega-bestseller Anh Do. Description Ants don't bully each other, hornets don't hold grudges, and butterflies certainly didn't spend the whole of lunchtime being gross and jealous. Amber always loved insects, even before the day her life changed forever. But now she feels something different. Something more…powerful. And controlling her power might be the hardest thing Amber has ever done. Especially when she is running for her life. Who is the mysterious Firefighter? What connection does he have to Amber's old life? And, most importantly, does Amber have what it takes to truly become … Skydragon? About the Author Anh Do is one of Australia's best-loved storytellers. His series, including Wolf Girl, E-Boy and WeirDo are adored by millions of kids around the country. Price: AU $15.99 NZ $17.99 ISBN: 9781760876364 Format: B Package Type: PAPERBACK Dimensions: 198h x 128w mm Extent: 224 pages Bic1: Bic2: <Unrelated Table> Author now living: Beecroft, Sydney A&U Children’s AD AUSTRALIA OCTOBER 2020 Skydragon 24 copy dumpbin A&U Point of Sale Pack includes 24 copies of Skydragon plus a free dumpbin, mobile, header, shelftalker and two posters. Description Pack includes 24 copies of Skydragon plus a free dumpbin, mobile, header, shelftalker and two posters. About the Author Price: AU $383.76 NZ $431.76 ISBN: 9324551076477 Format: Pack Package Type: PACK Dimensions: 0h x 0w mm Extent: 0 pages Bic1: Bic2: <Unrelated Table> Author now living: A & U Children AUSTRALIA OCTOBER 2020 Skydragon 24 copy pack A&U Point of Sale Pack includes 24 copies of Skydragon plus a free mobile, header, shelftalker and two posters. -

Children's Horror, PG-13 and the Emergent Millennial Pre-Teen

Children Beware! Children’s horror, PG-13 and the emergent Millennial pre-teen Filipa Antunes A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies December 2015 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Filipa Antunes “Children beware!” Abstract This thesis is a study of the children’s horror trend of the 1980s and 1990s focused on the transformation of the concepts of childhood and horror. Specifically, it discusses the segmentation of childhood to include the pre-teen demographic, which emerges as a distinct Millennial figure, and the ramifications of this social and cultural shift both on the horror genre and the entertainment industry more broadly, namely through the introduction of the deeply impactful PG-13 rating. The work thus adds to debates on children and horror, examining and questioning both sides: notions of suitability and protection of vulnerable audiences, as well as cultural definitions of the horror genre and the authority behind them. The thesis moreover challenges the reasons behind academic dismissal of these texts, pointing out their centrality to on-going discussions over childhood, particularly the pre-teen demographic, and suggesting a different approach to the -

Reasoning and Sense Making in Data Analysis and Statistics Beth Chance, Henry Kranendonk, Mike Shaughnessy

1 Reasoning and Sense Making in Data Analysis and Statistics Beth Chance, Henry Kranendonk, Mike Shaughnessy Key Elements of Statistical Reasoning • Analyzing data. Gaining insight about a solution to a statistical research question by representations and numerical summaries. • Modeling distributions. Developing probability models to describe long-run behavior of observations of a random variable. • Connecting statistics and probability. Recognizing variability as an essential focus of statistics and understanding the role of probability in statistical reasoning to make decisions under uncertainty. • Interpreting designed statistical studies. Drawing appropriate conclusions from the data and interpreting results from designed statistical studies using inference. Habits of Mind in Statistical Thinking Analyzing a problem Looking for patterns and relationships by- • describing overall patterns inthe data; • analyzing and explanation variation; • looking for hidden structure in the data; • making preliminary deductions and conjectures. Implementing a strategy Selecting representations or procedures by- • choosing and critiquing data collection strategies based on the question; • creating meaningful graphical representations and numerical summaries; • considering the random mechanisms behind the data; • drawing conclusions beyond the data. Monitoring one's progress Evaluating a chosen strategy by- • comparing various graphical and numerical representations; • comparing various interpretations of the data; • evaluating the consistency of an