Modern American Art in the Collection of John and Joanne Payson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert M. La Follette School of Public Policy Commencement Address

Robert M. La Follette School of Public Policy Commencement Address May 19, 2013 Bob Lang Thank you for inviting me to be a part of the celebration of your commencement -- graduation from the University of Wisconsin's Robert M. La Follette School of Public Policy. I have had the privilege of serving in Wisconsin's Legislative Fiscal Bureau with many La Follette graduates, including the 10 who are currently colleagues of mine at the Bureau. I am honored to be with you today. ____________________________ I have two favorite commencement speeches. The first, written 410 years ago, was not delivered to a graduating class, but rather, to an individual. It was, however, a commencement address in the true meaning of the word -- that is to recognize a beginning -- a transition from the present to the future. And, in the traditional sense of commencement speeches, was filled with advice. The speech was given by a father to his son, in Shakespeare's Hamlet. Polonius, chief councilor to Denmark's King Claudius, gives his son Laertes sage advice as the young man patiently waits for his talkative father to complete his lengthy speech and bid him farewell before the son sets sail for France to Page 1 continue his studies. "Those friends thou hast, grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel." "Give every man thine ear, but few thy voice." "Neither a borrower nor a lender be." "This above all, to thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man." The second of my favorite commencement addresses was delivered to a graduating college class by Thornton Mellen. -

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions

Checklist of Anniversary Acquisitions As of August 1, 2002 Note to the Reader The works of art illustrated in color in the preceding pages represent a selection of the objects in the exhibition Gifts in Honor of the 125th Anniversary of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Checklist that follows includes all of the Museum’s anniversary acquisitions, not just those in the exhibition. The Checklist has been organized by geography (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) and within each continent by broad category (Costume and Textiles; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints, Drawings, and Photographs; Sculpture). Within each category, works of art are listed chronologically. An asterisk indicates that an object is illustrated in black and white in the Checklist. Page references are to color plates. For gifts of a collection numbering more than forty objects, an overview of the contents of the collection is provided in lieu of information about each individual object. Certain gifts have been the subject of separate exhibitions with their own catalogues. In such instances, the reader is referred to the section For Further Reading. Africa | Sculpture AFRICA ASIA Floral, Leaf, Crane, and Turtle Roundels Vests (2) Colonel Stephen McCormick’s continued generosity to Plain-weave cotton with tsutsugaki (rice-paste Plain-weave cotton with cotton sashiko (darning the Museum in the form of the gift of an impressive 1 Sculpture Costume and Textiles resist), 57 x 54 inches (120.7 x 115.6 cm) stitches) (2000-113-17), 30 ⁄4 x 24 inches (77.5 x group of forty-one Korean and Chinese objects is espe- 2000-113-9 61 cm); plain-weave shifu (cotton warp and paper cially remarkable for the variety and depth it offers as a 1 1. -

Download File

The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Anne Claire Diebel All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel The history of personality in American literature has surprisingly little to do with the differentiating individuality we now tend to associate with the term. Scholars of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American culture have defined personality either as the morally vacuous successor to the Protestant ideal of character or as the equivalent of mass-media celebrity. In both accounts, personality is deliberately constructed and displayed. However, hiding in American writings of the long modernist period (1880s–1940s) is a conception of personality as the innate capacity, possessed by few, to attract attention and elicit projection. Skeptical of the great American myth of self-making, such writers as Henry James, Theodore Dreiser, Gertrude Stein, Nathanael West, and Langston Hughes invented ways of representing individuals not by stable inner qualities but by their fascinating—and, often, gendered and racialized—blankness. For these writers, this sense of personality was not only an important theme and formal principle of their fiction and non-fiction writing; it was also a professional concern made especially salient by the rise of authorial celebrity. This dissertation both offers an alternative history of personality in American literature and culture and challenges the common critical assumption that modernist writers took the interior life to be their primary site of exploration and representation. -

2018-2019 Annual Report

2018-2019 annuAl report THE MONTREAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS CITED AS MODEL EXAMPLE IN THE OECD AND ICOM’S INTERNATIONAL GUIDE “The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the International Council of Museums (ICOM) recognized the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ pioneering role in their guide launched in December 2018, Culture and Local Development: Maximising the Impact. Guide for Local Governments, Communities and Museums. This remarkable validation from two major international economic and cultural institutions will enable us to disseminate our message ever farther, so as to strengthen the role of culture and expand the definition of trailblazing museums, like the MMFA, that are fostering greater inclusion and wellness.” – Nathalie Bondil The Museum is cited in 5 of the 16 international case studies in the guide: a remarkable nod to our institution’s actions that stem from a humanist, innovative and inclusive vision. Below are a few excerpts from the publication that is available online at www.oedc.org: 1. Partnering for urban regeneration 3. Partnership for education: EducArt 5. Promoting inclusiveness, health and Regarding the MMFA’s involvement in creating the digital platform, Quebec, Canada well-being: A Manifesto for a Humanist Zone Éducation-Culture in 2016, in collaboration Launched in 2017 by the MMFA, EducArt gives Fine Arts Museum with Concordia University and the Ville de Montreal: secondary school teachers across the province access “As part of the Manifesto for a Humanist Fine “The project … has its roots in a common vision [of to an interdisciplinary approach to teaching the Arts Museum written by Nathalie Bondil,1 the the three institutions] to improve Montreal’s role as educational curriculum, based on the Museum’s MMFA has put forth a strong vision of the social a city of knowledge and culture. -

Hudson River at West Point)

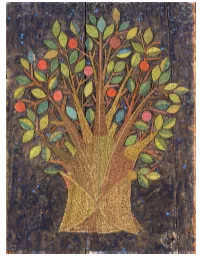

Search Collections "True religion shows its influence in every part of our conduct; it is like the sap of a living tree, which penetrates the most distant boughs."--William Penn, 1644-1718. From the series Great Ideas of Western Man. 1961 Vin Giuliani Born: New York 1930 painted wood on wood 23 1/2 x 17 1/2 in. (59.6 x 44.6 cm) Smithsonian American Art Museum Gift of Container Corporation of America 1984.124.106 Not currently on view Keywords Landscape - tree painting metal - nails paint - oil wood wood About Vin Giuliani Born: New York 1930 Search Collections Fields and Flowers ca. 1930-1935 William H. Johnson Born: Florence, South Carolina 1901 Died: Central Islip, New York 1970 watercolor and pencil on paper 14 1/8 x 17 3/4 in. (35.9 x 45.0 cm) Smithsonian American Art Museum Gift of the Harmon Foundation 1967.59.8 Not currently on view About William H. Johnson Born: Florence, South Carolina 1901 Died: Central Islip, New York 1970 More works in the collection by William H. Johnson Online Exhibitions • SAAM :: William H. Johnson • Online Exhibitions / SAAM • Highlights from the Smithsonian American Art Museum • Highlights from the Smithsonian American Art Museum • Cottingham - More to It!: The Whole Story • Cottingham - More to It!: The Whole Story • S C E N E S O F A M E R I C A N L I F E • M O D E R N I S M & A B S T R A C T I O N • Highlights from the Smithsonian American Art Museum • Online Exhibitions / SAAM Classroom Resources • William H. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Duchamp's Readymades

INTRODUCTION: DUCHAMP’S READYMADES — A REEVALUATION In a poll conducted for Gordon’s Gin, the 2004 sponsor of the Turner Prize, a large majority of the 500 leading artists, dealers, critics and curators surveyed named Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (Fig. 1.8) the work of art that has had the highest impact on contemporary art today. The urinal that in April 1917 was turned around, signed R. Mutt, handed in to but then refused (or at least displaced) from the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York still seems to mock and destabilize the whole horizon of expectance that works of art generate: skill, originality, taste, aesthetic value, difference from utilitarian technology, distance from bodily functions, even stable objecthood. Although many observers worry that the art institution has long since domesticated and commercialized the avant-gardist riot that Fountain took part in initiating, this object—albeit lost almost immediately after it was conceived—retains its status as an ever- flowing source for the disruptive and subversive energy in which contemporary art forms, at least desire to, participate. Whereas its closest competitor in the same poll, Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon from 1907, makes its revolution still in the domain of form—as if, in Braque’s words, Picasso had drunk petroleum in order to spit fire at the canvas—Fountain and its small family of other readymades make their riot by completely abandoning the battlefield of forms, what Duchamp termed the retinal. On the one hand, by appropriating pieces of technology that were not produced by Duchamp himself but by machines—a urinal, a bottle dryer, a dog comb, a snow shovel, an art reproduction, and so on—the readymades bring attention to what we could call the thingness of art: that despite all the transformations to which the artist can subject artistic materials, there is still a leftover of something pre-given, a naked materiality imported from the real, non-imaginary world. -

Download Lot Listing

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Wednesday, May 10, 2017 NEW YORK IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART EUROPEAN & AMERICAN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION Wednesday, May 10, 2017 at 11am EXHIBITION Saturday, May 6, 10am – 5pm Sunday, May 7, Noon – 5pm Monday, May 8, 10am – 6pm Tuesday, May 9, 9am – Noon LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $40 INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART 1-118 Elsie Adler European 1-66 The Eileen & Herbert C. Bernard Collection American 67-118 Charles Austin Buck Roberta K. Cohn & Richard A. Cohn, Ltd. POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 119-235 A Connecticut Collector Post-War 119-199 Claudia Cosla, New York Contemporary 200-235 Ronnie Cutrone EUROPEAN ART Mildred and Jack Feinblatt Glossary I Dr. Paul Hershenson Conditions of Sale II Myrtle Barnes Jones Terms of Guarantee IV Mary Kettaneh Information on Sales & Use Tax V The Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois Buying at Doyle VI Carol Mercer Selling at Doyle VIII A New Jersey Estate Auction Schedule IX A New York and Connecticut Estate Company Directory X A New York Estate Absentee Bid Form XII Miriam and Howard Rand, Beverly Hills, California Dorothy Wassyng INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Private Beverly Hills Collector The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz sold for the benefit of the Bard Graduate Center A New England Collection A New York Collector The Jessye Norman ‘White Gates’ Collection A Pennsylvania Collection A Private -

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan. 31 – May 31, 2015 Exhibition Checklist DOWN AT CONEY ISLE, 1861-94 1. Sanford Robinson Gifford The Beach at Coney Island, 1866 Oil on canvas 10 x 20 inches Courtesy of Jonathan Boos 2. Francis Augustus Silva Schooner "Progress" Wrecked at Coney Island, July 4, 1874, 1875 Oil on canvas 20 x 38 1/4 inches Manoogian Collection, Michigan 3. John Mackie Falconer Coney Island Huts, 1879 Oil on paper board 9 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches Brooklyn Historical Society, M1974.167 4. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene, c. 1879 Oil on canvas 12 x 20 inches Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Bequest of Annie Swan Coburn (Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn), 1934:3-10 5. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene with Acrobats, c. 1879-81 Oil on canvas 6 x 9 inches Collection Max N. Berry, Washington, D.C. 6. William Merritt Chase At the Shore, c. 1884 Oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 34 1/4 inches Private Collection Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Page 1 of 19 Exhibition Checklist, Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861 – 2008 12-15-14-ay 7. John Henry Twachtman Dunes Back of Coney Island, c. 1880 Oil on canvas 13 7/8 x 19 7/8 inches Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 1956.010 8. William Merritt Chase Landscape, near Coney Island, c. 1886 Oil on panel 8 1/8 x 12 5/8 inches The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, N.Y., Gift of Mary H. Beeman to the Pruyn Family Collection, 1995.12.7 9. -

George Bush - the Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin

George Bush - The Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin Introduction AMERICAN CALIGULA 47,195 bytes THE HOUSE OF BUSH: BORN IN A 1 33,914 bytes BANK 2 THE HITLER PROJECT 55,321 bytes RACE HYGIENE: THREE BUSH 3 51,987 bytes FAMILY ALLIANCES THE CENTER OF POWER IS IN 4 51,669 bytes WASHINGTON 5 POPPY AND MOMMY 47,684 bytes 6 BUSH IN WORLD WAR II 36,692 bytes SKULL AND BONES: THE RACIST 7 56,508 bytes NIGHTMARE AT YALE 8 THE PERMIAN BASIN GANG 64,269 bytes BUSH CHALLENGES 9 YARBOROUGH FOR THE 110,435 bytes SENATE 10 RUBBERS GOES TO CONGRESS 129,439 bytes UNITED NATIONS AMBASSADOR, 11 99,842 bytes KISSINGER CLONE CHAIRMAN GEORGE IN 12 104,415 bytes WATERGATE BUSH ATTEMPTS THE VICE 13 27,973 bytes PRESIDENCY, 1974 14 BUSH IN BEIJING 53,896 bytes 15 CIA DIRECTOR 174,012 bytes 16 CAMPAIGN 1980 139,823 bytes THE ATTEMPTED COUP D'ETAT 17 87,300 bytes OF MARCH 30, 1981 18 IRAN-CONTRA 140,338 bytes 19 THE LEVERAGED BUYOUT MOB 67,559 bytes 20 THE PHONY WAR ON DRUGS 26,295 bytes 21 OMAHA 25,969 bytes 22 BUSH TAKES THE PRESIDENCY 112,000 bytes 23 THE END OF HISTORY 168,757 bytes 24 THE NEW WORLD ORDER 255,215 bytes 25 THYROID STORM 138,727 bytes George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin With this issue of the New Federalist, Vol. V, No. 39, we begin to serialize the book, "George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography," by Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin. -

Wavelength (November 1984)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 11-1984 Wavelength (November 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (November 1984) 49 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I ~N0 . 49 n N<MMBER · 1984 ...) ;.~ ·........ , 'I ~- . '· .... ,, . ----' . ~ ~'.J ··~... ..... 1be First Song • t "•·..· ofRock W, Roll • The Singer .: ~~-4 • The Songwriter The Band ,. · ... r tucp c .once,.ts PROUDLY PR·ESENTS ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••••• • •• • • • • • • • ••• •• • • • • • •• •• • •• • • • •• ••• •• • • •• •••• ••• •• ••••••••••• •••••••••••• • • • •••• • ••••••••••••••• • • • • • ••• • •••••••••••••••• •••••• •••••••• •••••• •• ••••••••••••••• •••••••• •••• .• .••••••••••••••••••:·.···············•·····•••·• ·!'··············:·••• •••••••••••• • • • • • • • ...........• • ••••••••••••• .....•••••••••••••••·.········:· • ·.·········· .....·.·········· ..............••••••••••••••••·.·········· ............ '!.·······•.:..• ... :-=~=···· ····:·:·• • •• • •• • • • •• • • • • • •••••• • • • •• • -

Matters of Life and Death, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Hyman Bloo

HYMAN BLOOM Born Brunoviski, Latvia, 1913 Died 2009 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Hyman Bloom American Master, Alexandre Gallery, New York 2013 Alpha Gallery, Boston Massachusetts Hyman Bloom Paintings: 1940 – 2005, White Box, New York 2006 Hyman Bloom: A Spiritual Embrace, The Danforth Museum, Framingham, Massachusetts. Travels to Yeshiva University, New York in 2009. 2002 Color & Ecstasy: The Art of Hyman Bloom, The National Academy of Design, New York 2001 Hyman Bloom: The Lubec Woods, Bates College, Museum of Art. Traveled to Olin Arts Center, Lewiston Maine. 1996 The Spirits of Hyman Bloom: Sixty Years of Painting and Drawing, Fuller Museum, Brockton, Massachusetts 1992 Hyman Bloom: Paintings and Drawings, The Art Gallery, University of New Hampshire, Durham 1990 Hyman Bloom: “Overview” 1940-1990, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1989 Hyman Bloom Paintings, St. Botolph Club, Boston 1983 Hyman Bloom: Recent Paintings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1975 Hyman Bloom: Recent Paintings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1972 Hyman Bloom Drawings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1971 Hyman Bloom Drawings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York 1968 The Drawings of Hyman Bloom, University of Connecticut of Museum of Art, Storrs. Travels to the San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Boston University School of Fine and Applied Arts Gallery, Boston. 1965 Hyman Bloom Landscape Drawings 1962-1964, Swetzoff Gallery, Boston 1957 Drawings by Hyman Bloom, Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH. Travels to The Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design; and the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT Hyman Bloom Drawings, Swetzoff Gallery, Boston 1954 Hyman Bloom, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston.