Stony Brook University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociology of Religion, Lundscow, Chapter 7, Cults

Sociology of Religion , Sociology 3440-090 Summer 2014, University of Utah Dr. Frank J. Page Office Room 429 Beh. Sci., Office Hours: Thursday - Friday, Noon – 4:00-pm Office Phone: (801) 531-3075 Home Phone: (801) 278-6413 Email: [email protected] I. Goals: The primary goal of this class is to give students a sociological understanding of religion as a powerful, important, and influential social institution that is associated with many social processes and phenomena that motivate and influence how people act and see the world around them. The class will rely on a variety of methods that include comparative analysis, theoretical explanations, ethnographic studies, and empirical studies designed to help students better understand religion and its impact upon societies, global-international events, and personal well-being. This overview of the nature, functioning, and diversity of religious institutions should help students make more discerning decisions regarding cultural, political, and moral issues that are often influenced by religion. II. Topics To Be Covered: The course is laid out in two parts. The first section begins with a review of conventional and theoretical conceptions of religion and an overview of the importance and centrality of religion to human societies. It emphasizes the diversity and nature of "religious experience" in terms of different denominations, cultures, classes, and individuals. This is followed by overview of sociological assumptions and theories and their application to religion. A variety of theoretical schools including, functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory, sociology of knowledge, sociobiology, feminist theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodern and critical theory will be addressed and applied to religion. -

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

The Morning Line

THE MORNING LINE DATE: Tuesday, June 7, 2016 FROM: Melissa Cohen, Michelle Farabaugh Emily Motill PAGES: 19, including this page C3 June 7, 2016 Broadway’s ‘The King and I’ to Close By Michael Paulson Lincoln Center Theater unexpectedly announced Sunday that it would close its production of “The King and I” this month. The sumptuous production, which opened in April of 2015, won the Tony Award for best musical revival last year, and had performed strongly at the box office for months. But its weekly grosses dropped after the departure of its Tony-winning star, Kelli O’Hara, in April. Lincoln Center, a nonprofit, said it would end the production on June 26, at which point it will have played 538 performances. A national tour is scheduled to begin in November. The show features music by Richard Rodgers and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. The revival is directed by Bartlett Sher. C3 June 7, 2016 No More ‘Groundhog Day’ for One Powerful Producer By Michael Paulson Scott Rudin, a prolific and powerful producer on Broadway and in Hollywood, has withdrawn from a much- anticipated project to adapt the popular movie “Groundhog Day” into a stage musical. The development is abrupt and unexpected, occurring just weeks before the show is scheduled to begin performances at the Old Vic Theater in London. “Groundhog Day” is collaboration between the songwriter Tim Minchin and the director Matthew Warchus, following their success with “Matilda the Musical.” The new musical is scheduled to run there from July 15 to Sept. 17, and had been scheduled to begin performances on Broadway next January; it is not clear how Mr. -

Golden Rules (Bill Maher)

localLEGEND Golden Rules Bill Maher may be one of the nation’s most outspoken cultural critics, but a part of him is still that innocent boy from River Vale. BY PATTI VERBANAS HE RULES FOR LIFE, according to Bill Maher, are unshakable belief in something absurd, it’s amazing how convoluted really quite simple: Treat your fellow man as you wish their minds become, how they will work backward to justify it. We to be treated. Be humane to all species. And, most make the point in the movie: Whenever you confront people about importantly, follow your internal beliefs — not those the story of Jonah and the whale — a man lived in a whale for three thrust upon you by government, religion, or conventional days — they always say, “The Bible didn’t say it was a whale. The thinking. If you question things, you cannot go too far wrong. Bible said it was a big fish.” As if that makes a difference. TMaher, the acerbic yet affable host of HBO’s Real Time, author of New Rules: Polite Musings from a Timid Observer, and a self-described What do you want viewers to take away from this film? “apatheist” (“I don’t know what happens when I die, and I don’t I want them to have a good time. It’s a comedy. Beyond that, I would care”), recently released his first feature film, Religulous, a satirical hope that the people who came into the theater who are already look at the state of world religions. Here he gets real with New Jersey sympathetic to my point of view would realize that there’s millions Life about faith, his idyllic childhood in River Vale, and why the of people like that — who I would call “rationalists” — and they best “new rule” turns out to be an old one. -

Publishers and ISBN Prefixes

Date: 10/24/2013 Publishers and ISBN Prefixes Public Imprint Prefix Absolute Press 0-948230 0-9506785 1-4729 1-899791 1-904573 1-906650 Adlard Coles 0-229 0-7136 1-4081 1-4729 Aerie 0-8125 0-938819 1-4299 1-4668 1-55902 Arden Shakespeare 1-904271 AVA Publishing 2-88479 2-940373 2-940411 2-940496 BCF Books 0-9550026 Bedford/St. Martin's 0-312 0-314 0-324 0-395 0-495 0-534 0-538 0-547 0-618 0-669 0-7593 0-7895 0-87779 1-4130 1-4180 1-4188 1-4266 1-4282 1-4299 1-4576 Page 1 Date: 10/24/2013 Publishers and ISBN Prefixes Public Imprint Prefix Bedford/St. Martin's 1-55431 2-03 Behind the Wheel 1-4272 Berg Publishers 0-485 0-8264 0-85496 0-907582 1-8452 1-84520 1-84788 1-85973 Bloomsbury Academic 0-225 0-264 0-304 0-340 0-485 0-520 0-567 0-7131 0-7136 0-7185 0-7201 0-7220 0-7475 0-8044 0-8192 0-8264 0-85305 0-85496 0-85532 0-85785 0-86012 0-86187 0-87609 0-904286 0-907582 0-907628 0-950688 0-9506882 1-4081 1-4088 Page 2 Date: 10/24/2013 Publishers and ISBN Prefixes Public Imprint Prefix Bloomsbury Academic 1-4411 1-4482 1-4725 1-4729 1-55540 1-55587 1-56338 1-62356 1-62892 1-78093 1-84190 1-84371 1-84520 1-84706 1-84714 1-84725 1-84788 1-84930 1-84966 1-85285 1-85539 1-85567 1-85973 1-86047 1-870626 1-871478 1-898149 1-900512 1-902459 1-905422 Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare 0-17 0-416 0-567 1-4080 1-4081 1-4411 1-4725 1-84480 1-903436 1-904271 Bloomsbury Methuen Drama 0-413 Page 3 Date: 10/24/2013 Publishers and ISBN Prefixes Public Imprint Prefix Bloomsbury Methuen Drama 0-416 0-7136 1-4081 1-4725 1-78093 Bloomsbury Press 1-59691 1-60819 1-62040 -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

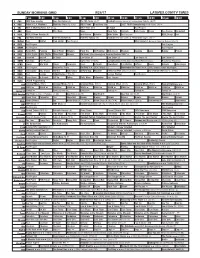

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2009 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum FEBRUARY 2009 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY VICKY CRISTINA IN BRUGES BOTTLE SHOCK ARSENIC AND IN BRUGES BARCELONA (2008-UK/Belgium) (2008) OLD LACE (2008-UK/Belgium) (2008-Spain/US) in widescreen in widescreen in widescreen in Catalan/English/Spanish w/ (1944) with Chris Pine, Alan with Cary Grant, Josephine English subtitles in widescreen with Colin Farrell, Brendan with Colin Farrell, Brendan Hull, Jean Adair, Raymond with Rebecca Hall, Scarlett Gleeson, Ralph Fiennes, Rickman, Bill Pullman, Gleeson, Ralph Fiennes, Johansson, Javier Bardem, Clémence Poésy, Eric Godon, Rachael Taylor, Freddy Massey, Peter Lorre, Priscilla Clémence Poésy, Eric Godon, Penelopé Cruz, Chris Ciarán Hinds. Rodriguez, Dennis Farina. Lane, John Alexander, Jack Ciarán Hinds. Messina, Patricia Clarkson. Carson, John Ridgely. Written and Directed by Written and Directed by Directed and Co-written by Written and Directed by Woody Allen. Martin McDonagh. Randall Miller. Directed by Martin McDonagh. Frank Capra. 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 12:30, 2:30, 4:30, 6:30 & 8:30pm 5 & 8:30pm 6 & 8:30pm 7 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 8 & 8:30pm 9 Lincoln's 200th Birthday THE VISITOR Valentine's Day THE VISITOR Presidents' Day 2 for 1 YOUNG MR. LINCOLN (2007) OUT OF AFRICA (2007) THE TALL TARGET (1951) (1939) in widescreen (1985) in widescreen with Dick Powell, Paula Raymond, Adolphe Menjou. with Henry Fonda, Alice with Richard Jenkins, Haaz in widescreen with Richard Jenkins, Haaz Directed by Anthony Mann. -

Comedians, Characters, Cable Guys & Copyright Convolutions

Legal Lessons in On-Stage Character Development: Comedians, Characters, Cable Guys & Copyright Convolutions Clay Calvert⊗ ABSTRACT This article addresses the trials and tribulations faced by stand-up comedians who seek copyright protection for on-stage characters they create, often during solo performances. The article initially explores the current, confused state of the law surrounding the copyrightability of fictional characters. The doctrinal muddle is magnified for comedians because the case law that addresses the fictional character facet of copyright jurisprudence overwhelmingly involves characters developed within the broader framework of plots and storylines found in traditional media artifacts such as books, comic strips, cartoons and movies. The article then deploys the 2014 federal court ruling in Azaria v. Bierko as a timely analytical springboard for addressing comedic-character copyright issues. Finally, the article offers multiple tips and suggestions for comedians and actors seeking copyright protection in their on- stage characters. I. INTRODUCTION The Whacky World of Jonathan Winters aired on television from 1972 through 1974.1 The humor of its star, Jonathan Winters,2 came primarily “from his construction of outrageously fantastic situations and characters.”3 Those characters included the Oldest Airline Stewardess4 and, perhaps most notably, ⊗ Professor & Brechner Eminent Scholar in Mass Communication and Director of the Marion B. Brechner First Amendment Project at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla. B.A., 1987, Communication, Stanford University; J.D. (Order of the Coif), 1991, McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific; Ph.D., 1996, Communication, Stanford University. Member, State Bar of California. The author thanks students Kevin Bruckenstein, Karilla Dyer, Alexa Jacobson, Tershone Phillips and Brock Seng of the University of Florida for their research, suggestions and editing assistance that contributed to this article. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

M a G a Z I N

JUNE VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 3 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ If I Had Wings: Producer Cynde Harmon’s Passion Project Soars to Festival Success PAGE 8 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! If I Had Wings: Producer Cynde Harmon’s Passion Project Soars to Festival Success INKTIP OFFERS: 8 • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily • Mandates Catered to Your Needs Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers • Personalized Customer Service 34 • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Teleplays 36 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers then InkTip – nobody. PASSIONATE and not the guys trying THEY OPENED DOORS that I would to make a buck.” have never been able to open.” – DWAIN WORRELL, OPERATOR – RICKIE BLACKWELL, MOBSTER KIDS PRODUCERS “We love InkTip. -

ISBN Prefix Summary Report Date: 2/24/16 Publisher Public Imprint ISBN Prefix A&C Black A&C Black 0-7136 0-7475 1-4081 1-4088 1-4725 1-4729 1-905615 Bedford/St

ISBN Prefix Summary Report Date: 2/24/16 Publisher Public Imprint ISBN Prefix A&C Black A&C Black 0-7136 0-7475 1-4081 1-4088 1-4725 1-4729 1-905615 Bedford/St. Martin's Bedford/St. Martin's 0-312 0-618 1-319 1-4576 Bloomsbury Academic AVA Publishing 2-88479061 2-88479104 2-88479105 2-88479110 2-94037301 2-94037306 2-94037314 2-94037315 2-94037317 2-94037319 2-94037323 2-94037329 2-94037335 2-94037340 2-94037343 2-94037344 2-94037346 2-94037350 2-94037351 2-94037356 2-94037357 2-94037360 2-94037361 2-94037363 2-94037368 2-94037370 2-94037371 2-94037372 2-94037374 2-94037375 2-94037376 2-94037380 2-94037381 2-94037382 2-94037383 2-94037384 Bloomsbury Academic AVA Publishing 2-94037385 2-94037387 2-94037388 2-94037389 2-94037390 2-94037391 2-94037398 2-94041100 2-94041104 2-94041105 2-94041107 2-94041108 2-94041109 2-94041110 2-94041112 2-94041113 2-94041115 2-94041116 2-94041117 2-94041118 2-94041121 2-94041122 2-94041126 2-94041127 2-94041128 2-94041129 2-94041130 2-94041131 2-94041133 2-94041134 2-94041135 2-94041136 2-94041138 2-94041139 2-94041140 2-94041141 2-94041142 2-94041144 2-94041147 2-94041148 2-94041149 2-94041150 2-94041151 2-94041152 2-94041153 2-94041155 2-94041156 2-94041158 2-94041161 2-94041162 2-94041163 2-94041166 Bloomsbury Academic AVA Publishing 2-94041171 2-94041174 2-94041175 2-94041176 2-94041177 2-94041178 2-94041179 2-94041181 2-94041186 2-94041187 2-94041190 2-94041192 2-94041194 2-94041195 2-94041197 2-94041198 2-94049621 Bloomsbury Academic 0-264 0-304 0-340 0-485 0-520 0-567 0-7136 0-7156 0-7201 0-7475