Systematic Review of the Long-Term Effects of Transgender Hormone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) in Drug Analysis

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-28-2005 The use of capillary electrophoresis (CE) in drug analysis Agnes D. Garcia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Other Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Garcia, Agnes D., "The use of capillary electrophoresis (CE) in drug analysis" (2005). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3928. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3928 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE USE OF CAPILLARY ELECTROPHORESIS (CE) IN DRUG ANALYSIS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in FORENSIC SCIENCE by Agnes D. Garcia 2005 To: Dean R. Bruce Dunlap College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Agnes D. Garcia, and entitled The Use of Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) in Drug Analysis, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Kenneth Furton Bruce McCord Jose R. Almirall, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 28,2005 The thesis of Agnes D. Garcia is approved. Dean R. Bruce Dunlap College of Arts and Sciences Dean Douglas Wartzok University Graduate School Florida International University, 2005 ii © Copyright 2005 by Agnes D. -

Miss.Julie ^ ^ Email:[email protected] Skype:[email protected] Whatsapp:+8618872220730

Miss.Julie ^ _ ^ Email:[email protected] Skype:[email protected] Whatsapp:+8618872220730 Raw anabolic steroid hormone powders from China with high purity&safe delivery Powder list : Testosterone enanthate Testosterone cypionate Testosterone propionate Testosterone-Sustanon250 Testosterone phenylpropionate Testosterone Acetate Testosterone decanoate Testosterone-Base Testosterone Isocaproate Testosterone undecanoate 17a-Methyl-1-Testosterone Fluoxymesterone(Halotesin) Mesterolone(Proviron) Methyltestosterone Trenbolone Acetate Trenbolone enanthate Trenbolone Base Metribolone Trenbolone Hexahydrobenzyl Carbonate Nandrolone decanoate Nandrolone Propionate Nandrolone phenylpropionate Nandrolone Mestanolone Drostanolone enanthate Drostanolone propionate (Masteron) 17a-Methyl-Drostanolone (Methasterone) Boldenone undecylenate (EQ) Methenolone Acetate Methenolone Enanthate (primobolin) Boldenoe cypionate Boldenoe Acetate Methandrostenolone (Dianabol) Oxandrolone (Anavar) Oxymetholone (Anadrol) Stanozolol (Winstrol) Turinabol Clostebol Acetate Anastrozloe (Arimidex) Clomiphene Citrate(Clomid) Exemestane Letrozole (Femara) Mifepristone Tamoxifen Citrate Semi-finished Injectable / Oral steroids: Test prop-----------100mg/ml 200mg/ml Test enan-----------250mg/ml 300mg/ml 400mg/ml 500mg/ml 600mg/ml Test cyp------------200mg/ml 250mg/ml 300mg/ml Test Sustanon-------200mg/ml 250mg/ml 300mg/ml 400mg/ml Deca----------------200mg/ml 250mg/ml Equipoise-----------200mg/ml 300mg/ml Tren ace------------100mg/ml 200mg/ml Tren enan-----------100mg/ml -

New Zealand Data Sheet 1. Product Name

NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME SUSTANON 250 (250 mg testosterone esters solution for injection) (SUSTANON) TESTOSTERONE ESTERS 250mg/mL for injection Presentations that are not currently available The vials are currently not available 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Name and strength of the active substances - testosterone proprionate 30mg testosterone phenylpropionate 60mg testosterone isocaproate 60mg testosterone decanoate 100mg All four compounds are esters of the natural hormone testosterone. The total amount of testosterone per 1 mL is 176mg. List of excipients - 1 mL arachis oil and the solution also contains 10 per cent benzyl alcohol. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Oily solution for intramuscular use. A clear, pale yellow solution. Each clear glass ampoule or vial contains 1 mL in arachis oil. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Testosterone replacement therapy in males for conditions associated with primary and secondary hypogonadism, either congenital or acquired. In female to male transsexuals: • masculinization Moreover, in men testosterone therapy may be indicated in osteoporosis caused by androgen deficiency. 4.2 Dose and method of administration In general, the dose should be adjusted according to the response of the individual patient. Dose Adults (incl. elderly): Usually, one injection of 1ml per three weeks is adequate. Paediatric population: Safety and efficacy in children and adolescents, have not yet been established. Pre-pubertal children treated with SUSTANON should be treated with caution (see Warnings and Precautions). SUSTANON contains benzyl alcohol and is contraindicatedin children under 3 years of age. Method of administration SUSTANON should be administered by deep intramuscular injection. -

Testosterone Art. 31

Annex I List of the names, pharmaceutical forms, strengths of the medicinal products, routes of administration, and marketing authorisation holders in the Member States 1 Member Marketing authorisation INN Invented name Strength Pharmaceutical Route of State holder form administration (in EEA) Austria Bayer Austria GmbH testosterone undecanoat Nebido 1000 mg/4 ml 1000 mg/4ml solution for intramuscular use Herbststrasse 6-10 Injektionslösung injection 1160 Wien Austria Austria Eli Lilly GmbH testosterone Axiron 30 mg/1,5 ml 30 mg/1,5ml gel cutaneous use Kölblgasse 8-10 Lösung zur 1030 Wien Anwendung auf der Austria Haut Austria Laboratoires Besins testosterone Testogel 25 mg - Gel 25 mg gel cutaneous use International SA im Beutel Rue de Bourg lÀbbè 3 75003 Paris France Austria Laboratoires Besins testosterone Testogel 50 mg - Gel 50 mg gel cutaneous use International SA im Beutel Rue de Bourg lÀbbè 3 75003 Paris France Austria ProStrakan Ltd. testosterone Tostran 2% - Gel 0.02 gel cutaneous use Galabank Business Park TD1 1QH Galashiels United Kingdom Austria Laboratoires Besins testosterone Androgel 25 mg - Gel 25 mg gel cutaneous use International SA im Beutel Rue de Bourg lÀbbè 3 75003 Paris France Austria Laboratoires Besins testosterone Androgel 50 mg - Gel 50 mg gel cutaneous use International SA im Beutel Rue de Bourg lÀbbè 3 75003 Paris France Austria N.V. Organon testosterone undecanoat Andriol Testocaps 40 40 mg capsule, soft oral use Kloosterstraat 6 mg - Kapseln 5349 AB Oss The Netherlands 2 Member Marketing authorisation INN Invented name Strength Pharmaceutical Route of State holder form administration (in EEA) Belgium Besins Healthcare testosterone Androgel 25 mg gel transdermal use Avenue Louise 287 1050 Brussels Belgium Belgium Besins Healthcare testosterone Androgel 50 mg gel transdermal use Avenue Louise 287 1050 Brussels Belgium Belgium Eli Lilly Benelux S.A.-N.V. -

An Update the Increasing Popularity of Anabolic Androgenic Steroids

Anabolic Androgenic Steroid Abuse in the United Kingdom; An Update The increasing popularity of anabolic androgenic steroids. Carrie Mullena, Benjamin J Whalleyb, Fabrizio Schifanoc, Julien S Bakerd a School of Computing, Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, PA1 2BE b School of Chemistry, Food and Nutritional Sciences, and Pharmacy, The University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, Berkshire, RG6 6AP c School of Life and Medical Sciences, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, AL10 9EU d Centre for Health and Exercise Science Research, Department of Sport, Physical Education and Health, Hong Kong Baptist University, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong. Correspondence Carrie Mullen, School of Computing, Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, PA1 2BE Tel 0044 141 848 3845 email [email protected] 7,081 Words Abstract Anabolic androgenic steroids (AASs) are prescribed for medical conditions related to low testosterone. Abuse of AASs has surged as they become increasingly recognised as potent image enhancement drugs. The primary goal of most abusers is to obtain what they consider to be a more attractive outward appearance. Abuse is complex. There are a vast range of AAS substances available, although due to their illicit nature, the true composition of AAS substances is difficult to evaluate. Users follow dosing patterns which incorporate a number This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/bph.14995 This article is protected by copyright. -

A28 Anabolic Steroids

Anabolic SteroidsSteroids A guide for users & professionals his booklet is designed to provide information about the use of anabolic steroids and some of the other drugs Tthat are used in conjunction with them. We have tried to keep the booklet free from technical jargon but on occasions it has proven necessary to include some medical, chemical or biological terminology. I hope that this will not prevent the information being accessible to all readers. The first section explaining how steroids work is the most complex, but it gets easier to understand after that (promise). The booklet is not intended to encourage anyone to use these drugs but provides basic information about how they work, how they are used and the possible consequences of using them. Anabolic Steroids A guide for users & professionals Contents Introduction .........................................................7 Formation of Testosterone ...............................................................8 Method of Action ..............................................................................9 How Steroids Work (illustration).......................................................10 Section 1 How Steroids are Used ....................................... 13 What Steroid? ................................................................................ 14 How Much to Use? ......................................................................... 15 Length of Courses? ........................................................................ 15 How Often to Use Steroids? -

Pdf 86.39 Kb

“Detection of Testosterone Esters in Blood Sample” Dr. G. Gmeiner, Dr. G. Forsdahl, Dr. Erceg (Seibersdorf Labor GmbH, Austria) Project Summary Testosterone is still regarded as the major contributor to steroid doping world-wide. Among the most common forms of application are injections of different sorts of esters. State-of-the-Art detection of Testosterone doping includes the quantification of the Testosterone /Epitestosterone – Ratio (T/E – ratio) as well as subsequent Isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS). Previous published studies of our research group have demonstrated that a comparably high percentage of testosterone preparations do not significantly differ from endogenous values of testosterone and markers of testosterone doping. Consequently when such preparations with endogenous – like 13CVPDB values are applied, IRMS - technology fails to detect testosterone doping. Direct detection of the testosterone ester leads to an unequivocal proof of doping with testosterone preparations, because such esters are not built endogenously. Previous studies indicate that a direct detection of testosterone esters in both hair and plasma is possible. Aim of the proposed project is the investigation and optimisation of the direct detection of testosterone esters in body fluids like serum, whole blood and stabilized blood with an already developed detection method using modern and sensitive technology. The project will gain information on diagnostic windows for detection of doping using testosterone esters and proper sampling conditions. Additional aim of the proposed project is to evaluate the suitability of already collected blood samples in doping control (e.g. samples collected for blood parameter measurement or growth hormone detection) for a possible reanalysis for testosterone esters. -

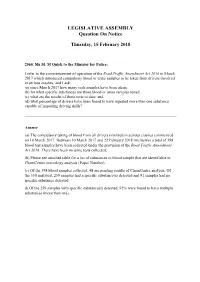

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question on Notice

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question On Notice Thursday, 15 February 2018 2560. Ms M. M Quirk to the Minister for Police; I refer to the commencement of operation of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016 in March 2017 which introduced compulsory blood or urine samples to be taken from drivers involved in serious crashes, and I ask: (a) since March 2017 how many such samples have been taken; (b) for what specific substances are those blood or urine samples tested; (c) what are the results of those tests to date; and (d) what percentage of drivers have been found to have ingested more than one substance capable of impairing driving skills? Answer (a) The compulsory taking of blood from all drivers involved in serious crashes commenced on 10 March 2017. Between 10 March 2017 and 22 February 2018 (inclusive) a total of 398 blood test samples have been collected under the provision of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016. There have been no urine tests collected. (b) Please see attached table for a list of substances in blood sample that are identifiable in ChemCentre toxicology analysis (Paper Number). (c) Of the 398 blood samples collected, 48 are pending results of ChemCentre analysis. Of the 350 analysed, 259 samples had a specific substance(s) detected and 91 samples had no specific substance detected. d) Of the 259 samples with specific substance(s) detected, 92% were found to have multiple substances (more than one). Detectable Substances in Blood Samples capable of identification by the ChemCentre WA. ACETALDEHYDE AMITRIPTYLINE/NORTRIPTYLINE -

WO 2012/148570 Al 1 November 2012 (01.11.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/148570 Al 1 November 2012 (01.11.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A61L 27/14 (2006.01) A61P 17/02 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, C08L 101/16 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, (21) International Application Number: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, PCT/US20 12/027464 MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (22) International Filing Date: OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, 2 March 2012 (02.03.2012) SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, 13/093,479 25 April 201 1 (25.04.201 1) US UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, WARSAW ORTHOPEDIC, INC. -

Georgia State Forensic Drugs

Comprehensive Forensic FT-IR Collection Library Listing – 4,286 spectra This extensive library contains materials not only of forensic interest but also for general problem solving and identification of unknown substances in industry and academia. The wide range of items include drugs, clandestine lab chemicals, explosives, paints, fabrics, dyes, polymers, inorganic compounds, pigments, adhesives, and other common materials. The library consists of 4,286 spectra that were acquired from a wide range of laboratories involved in forensic investigations. The collection includes the following classes of compounds: • Drugs of abuse, scheduled materials • Pharmaceuticals, vitamins and excipients • Clandestine lab materials and intermediates • Solvents, organic chemicals and hazardous chemicals • Accelerants • Lubricants and natural oils • Explosives, pyrotechnics, primers, powders and boosters • Herbal and plant material and fibers • Automobile paint vehicles, pigments, primers and clear coats • Textiles, natural and man-made fibers, carpet materials • Paints, coatings, varnishes, oils • Dyes and stains • Polymers, monomers, copolymers, plasticizers and rubbers • Inorganics, pigments, minerals and clays • Tape, adhesives, sealants, glues, caulks and putties • Crystal test derivatives and intermediates • Household chemicals, cleaning agents, surfactants and pesticide All spectra were measured using micro or macro Diamond ATR, thin films on salt windows or KBr pellets at 4 cm-1 spectral resolution. Comprehensive Forensic FT-IR Collection Index -

Network-Based Characterization of Drug-Protein Interaction Signatures

Tabei et al. BMC Systems Biology 2019, 13(Suppl 2):39 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12918-019-0691-1 RESEARCH Open Access Network-based characterization of drug-protein interaction signatures with a space-efficient approach Yasuo Tabei1*, Masaaki Kotera2, Ryusuke Sawada3 and Yoshihiro Yamanishi3,4 From The 17th Asia Pacific Bioinformatics Conference (APBC 2019) Wuhan, China. 14–16 January 2019 Abstract Background: Characterization of drug-protein interaction networks with biological features has recently become challenging in recent pharmaceutical science toward a better understanding of polypharmacology. Results: We present a novel method for systematic analyses of the underlying features characteristic of drug-protein interaction networks, which we call “drug-protein interaction signatures” from the integration of large-scale heterogeneous data of drugs and proteins. We develop a new efficient algorithm for extracting informative drug- protein interaction signatures from the integration of large-scale heterogeneous data of drugs and proteins, which is made possible by space-efficient representations for fingerprints of drug-protein pairs and sparsity-induced classifiers. Conclusions: Our method infers a set of drug-protein interaction signatures consisting of the associations between drug chemical substructures, adverse drug reactions, protein domains, biological pathways, and pathway modules. We argue the these signatures are biologically meaningful and useful for predicting unknown drug-protein interactions and are expected to contribute to rational drug design. Keywords: Drug-protein interaction prediction, Drug discovery, Large-scale prediction Background similar drugs are expected to interact with similar pro- Target proteins of drug molecules are classified into a pri- teins, with which the similarity of drugs and proteins are mary target and off-targets. -

Influence of the Use of Testosterone Associated with Physical

original article Influence of the use of testosterone associated with physical training on some hematologic and physical parameters in older rats with alloxan-induced diabetes Romeu Paulo Martins Silva1,2, Rodrigo Otávio dos Santos2, Nelson Eurípedes Matildes Junior2, Antônio Vicente Mundim3, Mario da Silva Garrote-Filho3, Pâmella Ferreira Rodrigues2, Nilson Penha-Silva3 ABSTRACT 1 Centro de Ciências da Saúde e Objective: This study investigated the possible blood changes in wistar rats elderly with and without Desporto, Universidade Federal do treatment with anabolic steroids submitted physical training. Materials and methods: Elderly rats Acre (UFAC), Rio Branco, AC, Brasil (32) were divided into four groups: normal (N), treated normal (NT), diabetic (D) and treated diabetic 2 Centro Universitário do Planalto de (DT). They were submitted to 20 sessions of swimming with overload (5% body weight), 40 min/ Araxá (Uniaraxá), Araxá, MG, Brasil 3 Instituto de Genética e Bioquímica, day for four weeks. The NT and DT groups received application of testosterone twice a week. At Universidade Federal de Uberlândia the end of the sessions, the animals were subjected to swimming until exhaustion and then killed (UFU), Uberlândia, MG, Brasil for removal of blood and visceral fat. We evaluated maximum swim time, weight of visceral fat, erythrogram, leukogram, lipidogram and serum levels of glucose, lactate, aspartate aminotransferase Correspondence to: and creatine kinase. The results were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Romeu Paulo Martins Silva Tukey test. Results: In elderly diabetic rats, the use of anabolic associated with physical training in Universidade Federal do Acre Instituto de Genética e Bioquímica older rats resulted in improvement in erythrogram, lipidogram and physical performance for high- BR 364, km 04 intensity aerobic exercise.