A Requiem for the Tennessee Summary Judgment Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 TNJ 09.Pdf

TennesseeThe Journal The weekly insiders newsletter on Tennessee government, politics, and business Vol. 46, No. 9 February 28, 2020 Will Bloomberg gambit pay off in Tennessee on Super Tuesday? Tennessee is hardly uncharted territory when it $114,000 by Biden, and $37,000 by Pete Buttigieg. Klo- comes to receiving attention from presidential hopefuls, buchar had rallies scheduled for Nashville on Friday but over the last several cycles it has been Republicans and Knoxville on Saturday, while surrogates made who have made the bigger effort to court primary voters appearances for other candidates. They included in the state than Democrats. Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms campaigning in This time around, Tennessee has become a top prior- Nashville for Biden on Friday. Earlier in the week, Sand- ity for one candidate in particular: Democrat Mike ers’ wife, Jane, visited Nashville and actress Ashley Judd Bloomberg, who is making his latest visit to the state on campaigned for Warren in Nashville and Memphis. Friday, his fourth since entering the race. The former Early indicators. This year’s early voting turnout New York mayor has spent $7.8 million through the was 13% below 2016 levels, a decrease attributable to middle of this week on broadcast TV, cable, digital, and the 90,000 fewer Republicans who cast ballots in a pri- radio ads in Tennessee, according to Advertising Analyt- mary in which President Donald Trump faces no serious ics. Bloomberg has also hired more than 40 staffers and opposition. Democrats trying to influence the wide- opened seven campaign offices around the state. open presidential nomination contest saw an increase of Bloomberg has been rolling out a series of blast- 41,000 voters, a 30% jump over 2016. -

The 2005-2006 Annual Report of the Tennessee Judiciary Is Dedicated to Supreme Court Justices E

The 2005-2006 Annual Report of the Tennessee Judiciary is dedicated to Supreme Court Justices E. Riley Anderson and Adolpho A. Birch, Jr., who retired August 31, 2006. Their service to the state and the administration of justice is gratefully acknowledged. “His leadership in helping make the court system more open and accessible to the public will be long remembered and appreciated.” Governor Phil Bredesen on the retirement of Justice E. Riley Anderson Justice Birch “His commitment to judicial fairness and impartiality is well known and the state has been fortunate to enjoy the benefits of his dedication for over 40 years.” Governor Phil Bredesen on the retirement of Justice Adolpho A. Birch, Jr. Justice Anderson Table of Contents Message from the Chief Justice & State Court Administrator --------------------------- 3 Justices E. Riley Anderson & Adolpho A. Birch, Jr.---------------------------------------- 4 Snapshots ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 6 Judicial Department Budget -------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Highlights ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 8 Court System Chart ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 9 Tennessee Supreme Court ---------------------------------------------------------------------10 Intermediate Appellate Courts ----------------------------------------------------------------11 Message from the TJC President--------------------------------------------------------------12 -

The 2004-2005 Annual Report of the Tennessee Judiciary Is Dedicated To

The 2004-2005 Annual Report of the Tennessee Judiciary is dedicated to Frank F. Drowota, III, in appreciation for his 35 years of service to the administration of justice Table of Contents Message from the Chief Justice & State Court Administrator ------------------ 3 Retired Chief Justice Frank F. Drowota, III -------------------------------------------- 4 A Year of Change ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 6 Judicial Department Budget -------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Year in Review --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Court System Chart ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 10 Tennessee Supreme Court -------------------------------------------------------------- 11 Intermediate Appellate Courts ---------------------------------------------------------- 12 Message from the TJC President ------------------------------------------------------ 13 Trial Court Judges by Judicial District ----------------------------------------------- 14 General Sessions & Juvenile Court Judges by County------------------------ 18 Municipal Court Judges & Clerks by City ------------------------------------------- 22 Appellate and Trial Court Clerks ------------------------------------------------------- 29 Court of the Judiciary --------------------------------------------------------------------- 34 Board of Professional Responsibility ------------------------------------------------ 34 Tennessee Board -

Morgan Keegan Sold to Raymond James in Blockbuster $930M Deal PAGE 18

January 14-20, 2011, Vol. 5, Issue 3 12 Health Care & Biotech St. Jude celebrates 50th anniversary 31 Food & Wine Fredric Koeppel »looks at the PINNACLE SEEKS PAY CuTS: Memphis-based regional air carrier Pinnacle Airlines Corp. is asking restaurant industry union employees to take a 5 percent salary reduction. » Page 11 forecast for 2012. Trading Hands Morgan Keegan sold to Raymond James in blockbuster $930M deal PAGE 18 Photo: Lance Murphey The fate of Morgan Keegan & Co. Inc., whose Downtown tower is pictured here, and its 1,000-plus employees now rests in the hands of St. Petersburg, Fla.-based Raymond James, which bought the Memphis investment firm from Regions Financial Corp. for $930 million. While Raymond James said it plans to base its Fixed Income and Public Finance busi- ness in Memphis – meaning many local workers might keep their jobs – the full extent of the deal won’t be known for some time. 20 Sports Without power forward Zach Randolph in the lineup, the Memphis Grizzlies are limping into this year’s nationally televised Martin Luther King Jr. Day game at FedExForum. DAILY DIGEST: PAGE 2 FINANCIAL serviCes: PAGE 8 DUNAVANT AWARDS PAGE 17 SMALL Business: PAGE 22 LAW TALK: PAGE 24 A Publication of The Daily News Publishing Co. | www.thememphisnews.com 2 January 14-20, 2012 www.thememphisnews.com weekly digest Get news daily from The Daily News, www.memphisdailynews.com. MAAR: Home Sales Drop division. plosive devices used in Iraq and Afghanistan else will be.” Kimberly-Clark brand name products against U.S. and other coalition troops. -

Non-Competition Agreements Evidence Issues in A

■ Non-competition agreements ■ Evidence issues in a church love triangle trial www.tba.org ARTICLES 14 FREE TO SHARE? GROKSTER DECISION SIDESTEPS INNOVATION/COPYRIGHT BATTLE, PUTS FOCUS ON BUSINESS STRATEGIES By David Moser 18 NEW RACE TO TENNESSEE AND GEORGIA COURTHOUSES OVER NON-COMPETITION AGREEMENTS By Don Benson and Stephanie Bauer Daniel EVIDENCE ISSUES IN A CHURCH LOVE TRIANGLE TRIAL 22 By Donald F. Paine NEWS & INFORMATION 6 Relief for Hurricane Katrina survivors swells; lawyers join together to help 7 Clark named to Tennessee Supreme Court 7 Indigent representation gets a boost 12 Actions from the Board of Professional Responsibility DEPARTMENTS 3 President’s Perspective: Heartbreak followed by action By Bill Haltom 5 Letter / Jest Is for All: By Arnie Glick 8 The Bulletin Board: News about TBA members On the Cover When the U.S. Supreme 2 9 4 0 Ye a r s : TBA sections — Court ruled in MGM People who know what you are talking about Studios Inc. v. Grokster By Suzanne Craig Robertson Ltd., copyright and technology development 30 Paine on Procedure: The unconstitutional non-uniform residential industries saw the outcome landlord and tenant act very differently. Read about By Donald F. Paine what the decision may mean for each side, begin- ning on page 14. Cover 31 Classified Advertising design by Barry Kolar. PRESIDENT’S PERSPECTIVE Hurricane Katrina Journal Staff Heartbreak followed Suzanne Craig Robertson, Editor [email protected] by action Landry Butler, Publications & Advertising Coordinator [email protected] Barry Kolar, Assistant Executive Director arly one warm spring morning some 24 years [email protected] ago, my bride and I boarded a train in E Atlanta and headed for our honeymoon. -

Letter to the Tennessee Revisor of Statutes

DocuSign Envelope ID: 429A8BA4-F3FD-4136-80B3-D2CE9E268985 Legal Clinic April 14, 2021 Ms. Paige Seals, Revisor of Statutes Office of Legal Services Tennessee General Assembly 9th Floor, Cordell Hull Building Nashville, TN 37243 Dear Ms. Seals: Public.Resource.Org (“Public Resource”) writes to respectfully request the Office of the Revisor and the Tennessee Code Commission (“TCC”) revise the Tennessee Code Annotated (“TCA”) to clarify that the TCA is in the public domain. The State of Tennessee currently claims copyright protection of the TCA. However, following the recent Supreme Court decision in Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org, Inc., the TCA is ineligible for such copyright protections.1 Thus, Public Resource also respectfully requests the removal of all indications of copyright protection from the TCA as such protection claims are obsolete.2 These changes are consistent with federal copyright law and with Tennessee’s policy of promoting public access to public government documents. Public Resource is a California-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation working to increase citizens’ access to the law. Public Resource appreciates Tennessee’s dedication to improve government transparency through the Tennessee Public Records Act and the Tennessee Open Meetings Acts. However, the copyrights claimed for the Tennessee Code Annotated prevent the full realizations of these aims. Following the decision in Georgia, under the government edicts doctrine, government officials cannot, for copyright purposes, “author” works they create in their official capacity.3 The TCA and the annotations within are government edicts, authored by the TCC in its official capacity, and are therefore ineligible for copyright protection. 1 140 S. -

T E N N E S S E E L a W Y E R S ' a S S O C I a T I O N F O R W O M E N

T E N N E S S E E L A W Y E R S ' A S S O C I A T I O N F O R W O M E N Empowerment Conference 2017: Women Who Win! E M P O W E R I N G W O M E N S I N C E 1 9 8 9 . TABLE OF CONTENTS Conference Schedule ...................................................................................... 1 Moderator, Panelist, and Speaker Biographies ....................................... 3 Ramona P. DeSalvo ..................................................................................................... 3 The Honorable Cornelia A. Clark ................................................................................ 4 The Honorable Julia Smith Gibbons ........................................................................... 5 Kim Harvey Looney ..................................................................................................... 6 Andrée Blumstein ........................................................................................................ 7 Dawn Deaner ............................................................................................................... 8 The Honorable Kim McMillan ..................................................................................... 9 The Honorable Brandon Gibson ................................................................................ 10 Linda Strite Murnane, Colonel, USAF, Ret. ............................................................. 11 Heather Hubbard ....................................................................................................... 14 Kyonzté -

TNGPA List of Governmental Leaders Website

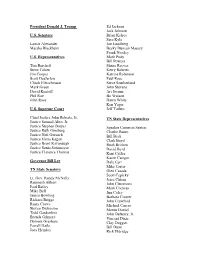

President Donald J. Trump Ed Jackson Jack Johnson U.S. Senators Brian Kelsey Sara Kyle Lamar Alexander Jon Lundberg Marsha Blackburn Becky Duncan Massey Frank Niceley U.S. Representatives Mark Pody Bill Powers Tim Burchett Shane Reeves Steve Cohen Kerry Roberts Jim Cooper Katrina Robinson Scott DesJarlais Paul Rose Chuck Fleischmann Steve Southerland Mark Green John Stevens David Kustoff Art Swann Phil Roe Bo Watson John Rose Dawn White Ken Yager U.S. Supreme Court Jeff Yarbro Chief Justice John Roberts, Jr. TN State Representatives Justice Samuel Alito, Jr. Justice Stephen Breyer Speaker Cameron Sexton Justice Ruth Ginsburg Charlie Baum Justice Neil Gorsuch Bill Beck Justice Elena Kagan Clark Boyd Justice Brent Kavanaugh Rush Bricken Justice Sonia Sotomayor David Byrd Justice Clarence Thomas Kent Calfee Karen Camper Governor Bill Lee Dale Carr Mike Carter TN State Senators Glen Casada Scott Cepicky Lt. Gov. Randy McNally Jesse Chism Raumesh Akbari John Clemmons Paul Bailey Mark Cochran Mike Bell Jim Coley Janice Bowling Barbara Cooper Richard Briggs John Crawford Rusty Crowe Michael Curcio Steven Dickerson Martin Daniel Todd Gardenhire John DeBerry, Jr. Brenda Gilmore Vincent Dixie Dolores Gresham Clay Doggett Ferrell Haile Bill Dunn Joey Hensley Rick Eldridge Jeremy Faison Jay Reedy Andrew Farmer Tim Rudd Bob Freeman Iris Rudder Ron Gant Lowell Russell Johnny Garrett Jerry Sexton Bruce Griffey Johnny Shaw Rusty Grills Paul Sherrell Yusef Hakeem Robin Smith Curtis Halford Mike Sparks Mark Hall Rick Staples G.A. Hardaway Mike Stewart Kirk Haston Bryan Terry David Hawk Dwayne Thompson Patsy Hazlewood Rick Tillis Esther Helton Chris Todd Gary Hicks, Jr. -

Judicial Selection in Tennessee: Deciding “The Decider”

JUDICIAL SELECTION IN TENNESSEE: DECIDING “THE DECIDER” * MARGARET L. BEHM & ** CANDI HENRY PROLOGUE.................................................................................................144 I. AN OVERVIEW OF JUDICIAL SELECTION IN TENNESSEE........................145 A. 2013—The State of Play of Judicial Selection in Tennessee..145 B. Historical Background, 1796–1970.........................................149 1. The Rise of Merit Selection, Circa 1971...........................151 2. First Constitutional Challenge, 1972.................................153 3. Second Iteration of Merit Selection—The Return of Statewide Elections for the Supreme Court, 1973..........155 C. The Tennessee Plan, 1994–2013.............................................157 1. The Tennessee Plan Is Implemented and Legal Chaos Ensues .............................................................................159 2. A Decade Later, a New Controversy Erupts .....................163 3. A Sea Change in Tennessee Politics .................................166 D. Back to the State of Play: Where Are We & Where Should We Be Going?..............................................................................167 II. PERSONAL PERSPECTIVES ON JUDICIAL SELECTION IN TENNESSEE ....169 A. The Face of the Tennessee Judiciary, 1976–2013 ..................169 B. Thoughts on Moving Forward.................................................175 POSTSCRIPT ...............................................................................................178 * Margaret L. Behm is -

Tennessee Supreme Court Hears Arguments at the Nashville School of Law Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 The Torch NASHVILLE SCHOOL of LAW NEWSLETTER FEATURE STORY: TENNESSEE SUPREME COURT HEARS ARGUMENTS AT THE NASHVILLE SCHOOL OF LAW SPRING 2016 WHAT’S INSIDE: MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN NSL NEWS 3 Tennessee Supreme Court Hears Arguments 5 Judge Waverly Crenshaw Joins Board, Douglas Fisher Retires 6 Law School Pro Bono and Public Interest Summit 9 NSL Offers Juvenile Court Custody Clinic 10 NSL Hosts Virtual Law Clinics 11 Sports and Entertainment Law Society Formed 12 NSL Celebrates Investiture of Dean Koch FACULTY Carrying On 5 Moot Court Students Honor Tom Carlton 6 Faculty Profile: Carlton M. Lewis William L. Harbison Named The Tradition 7 Nashvillian of the Year 25 Faculty Notes The Nashville School of Law’s traditions are events. The enthusiasm at these events important. This edition of the newsletter reflects was remarkable, and we look forward to STUDENTS how our students and graduates honor these sponsoring additional events. We hope you 8 Grammy-Winning Student Hopes to Practice traditions and how our school community will attend the recognition dinner on Friday, Entertainment Law continues to make these traditions relevant June 10th at the Renaissance Nashville 9 Police Sergeant Blessed in today’s world. It is an exciting time to be Hotel. At this year’s dinner, Brenda and to be at NSL at the Nashville School of Law. Doug Hale will receive our Distinguished 14 2015 Cooper Term Graduation Graduates Award; Hal Hardin will receive 16 2015 Henry Term Graduation Our mission for the past 105 years has been our Distinguished Faculty Award; and we 23 2015–2016 Scholarships to prepare men and women to use their legal will recognize the historic achievements ALUMNI education to serve others. -

Official Results August 7, 2014 Early Voting and Absentee ONLY

Page: 1 of 25 8/26/2014 10:04:18 AM Official Results August 7, 2014 State Primary County General Early Voting and Absentee Summary ONLY Precincts Reported: 130 of 130 (100.00%) Registered Voters: 21,544 of 206,044 (10.46%) Ballots Cast: 21,544 Governor - REP (Vote for 1) REP Precincts Reported: 130 of 130 (100.00%) Total Times Cast 15,544 / 206,044 7.54% Candidate Party Total Mark Coonrippy Brown REP 505 Bill Haslam REP 13,716 Basil Marceaux, Sr. REP 393 Donald Ray McFolin REP 234 Total Votes 14,848 Governor - DEM (Vote for 1) DEM Precincts Reported: 130 of 130 (100.00%) Total Times Cast 5,698 / 206,044 2.77% Candidate Party Total Charles V. "Charlie" Brown DEM 1,278 Kennedy Spellman Johnson DEM 763 Wm. H. "John" McKamey DEM 1,966 Ron Noonan DEM 208 Total Votes 4,215 U.S. Senate - REP (Vote for 1) REP Precincts Reported: 130 of 130 (100.00%) Total Times Cast 15,544 / 206,044 7.54% Candidate Party Total Christian Agnew REP 263 Lamar Alexander REP 10,462 Joe Carr REP 3,304 George Shea Flinn REP 593 John D. King REP 126 Brenda S. Lenard REP 209 Erin Kent Magee REP 77 Total Votes 15,034 Page: 2 of 25 8/26/2014 10:04:18 AM U.S. Senate - DEM (Vote for 1) DEM Precincts Reported: 130 of 130 (100.00%) Total Times Cast 5,698 / 206,044 2.77% Candidate Party Total Terry Adams DEM 1,565 Gordon Ball DEM 1,227 Larry Crim DEM 434 Gary Gene Davis DEM 1,194 Total Votes 4,420 U.S. -

LAW Matters July 2021 Volume XXXIII No

LAW Matters July 2021 Volume XXXIII No. 3 Photo 187878698 / June © Chormail | Dreamstime.com In This Issue President’s Message 2 Hybrid August Membership Meeting—Ethical Issues for Attorneys Serving on Nonprofit Boards 3 Founder’s Spotlight: Barbara Moss 4 Past President’s Spotlight: Chancellor Rose Cantrell 5 Board Member Spotlight: President-Elect Shellie Handelsman 6 Recap of LAW June Membership Meeting and One Hour CLE 7 Lawmakers Enact a New Process for Constitutional Claims—But Is It Constitutional? 9 Member Spotlight: Sonia Hong 11 MGWS Save the Date/Amendment to the Criminal Justice Act Plan 12 Kudos & Job Opportunities 13 Sustaining Members 14 President’s Message 2021-2022 LAW BOARD OF DIRECTORS by Kimberly Faye Executive Board Kimberly Faye, President Shellie Handelsman, President-Elect I hope everyone had a wonderful Fourth of Emily Warth, Secretary July weekend! I enjoyed time with family and Leighann Ness, Treasurer watched the musical Hamilton, which is be- Brooke Coplon, 2nd Year Director Tabitha Robinson, 2nd Year Director coming a little tradition for me after watching Shundra Manning, 1st Year Director it last year on July 4th when it was released Courtney Orr, 1st Year Director to Disney Plus. One of my absolute favorite Rachel Berg, Archivist lines from the musical is, “I’m just like my Samantha Simpson, Archivist Amanda Bradley, Newsletter Editor country - I’m young, scrappy, and hungry, Hannah Kay Freeman, Newsletter Editor and I am not throwing away my shot.” While Devon Landman, Newsletter Editor thinking about that line and America’s Found- Caroline Sapp, Newsletter Editor ing Fathers, I started thinking about the histo- Sara Anne Quinn, Immediate Past President ry of LAW and our founding members.