Diverse Literature in Elementary School Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American History & Culture

IN September 2016 BLACK AMERICAsmithsonian.com Smithsonian WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM: REP. JOHN LEWIS BLACK TWITTER OPRAH WINFREY A WORLD IN SPIKE LEE CRISIS FINDS ANGELA Y. DAVIS ITS VOICE ISABEL WILKERSON LONNIE G. BUNCH III HEADING NATASHA TRETHEWEY NORTH BERNICE KING THE GREAT ANDREW YOUNG MIGRATION TOURÉ JESMYN WARD CHANGED WENDEL A. WHITE EVERYTHING ILYASAH SHABAZZ MAE JEMISON ESCAPE FROM SHEILA E. BONDAGE JACQUELINE WOODSON A LONG-LOST CHARLES JOHNSON SETTLEMENT JENNA WORTHAM OF RUNAWAY DEBORAH WILLIS SLAVES THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS SINGING and many more THE BLUES THE SALVATION DEFINING MOMENT OF AMERICA’S ROOTS MUSIC THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE OPENS IN WASHINGTON, D.C. SMITHSONIAN.COM SPECIAL�ADVERTISING�SECTION�|�Discover Washington, DC FAMILY GETAWAY TO DC FALL�EVENTS� From outdoor activities to free museums, your AT&T�NATION’S�FOOTBALL� nation’s capital has never looked so cool! CLASSIC�® Sept. 17 Celebrate the passion and tradition of IN�THE� the college football experience as the Howard University Bisons take on the NEIGHBORHOOD Hampton University Pirates. THE�NATIONAL�MALL NATIONAL�MUSEUM�OF� Take a Big Bus Tour around the National AFRICAN�AMERICAN�HISTORY�&� Mall to visit iconic sites including the CULTURE�GRAND�OPENING Washington Monument. Or, explore Sept. 24 on your own to find your own favorite History will be made with the debut of monument; the Martin Luther King, Jr., the National Mall’s newest Smithsonian Lincoln and World War II memorials Ford’s Th eatre in museum, dedicated to the African are great options. American experience. Penn Quarter NATIONAL�BOOK�FESTIVAL� CAPITOL�RIVERFRONT Sept. -

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson Raised in South Carolina and New York, Woodson always felt halfway home in each place. In vivid poems, she shares what it was like to grow up as an African American in the 1960s and 1970s, living with the remnants of Jim Crow and her growing awareness of the Civil Rights movement. Each line a glimpse into a child's soul as she searches for her place in the world. Why you'll like it:. poetry, touching, family, friendship About the Author: Jacqueline Woodson was born in Columbus, Ohio on February 12, 1963. She received a B.A. in English from Adelphi University in 1985. Before becoming a full-time writer, she worked as a drama therapist for runaways and homeless children in New York City. Her books include The House You Pass on the Way, I Hadn't Meant to Tell You This, and Lena. She won the Coretta Scott King Award in 2001 for Miracle's Boys. After Tupac and D Foster, Feathers, and Show Way won Newbery Honors. Brown Girl Dreaming won the E. B. White Read-Aloud Award in 2015. Her other awards include the Margaret A. Edwards Award for lifetime achievement in writing for young adults and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She was also selected as the Young People's Poet Laureate in 2015 by the Poetry Foundation. (Bowker Author Biography) Questions for Discussion 1. Brown Girl Dreaming is an award winning memoir written in verse. Do you enjoy this format for an autobiography? Even though each chapter/ verse is short, do you feel that you got a good sense of the setting or moment that Woodson was trying to convey? 2. -

Anti-Racism Resources

Anti-Racism Resources Prepared for and by: The First Church in Oberlin United Church of Christ Part I: Statements Why Black Lives Matter: Statement of the United Church of Christ Our faith's teachings tell us that each person is created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and therefore has intrinsic worth and value. So why when Jesus proclaimed good news to the poor, release to the jailed, sight to the blind, and freedom to the oppressed (Luke 4:16-19) did he not mention the rich, the prison-owners, the sighted and the oppressors? What conclusion are we to draw from this? Doesn't Jesus care about all lives? Black lives matter. This is an obvious truth in light of God's love for all God's children. But this has not been the experience for many in the U.S. In recent years, young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts. Black women in crisis are often met with deadly force. Transgender people of color face greatly elevated negative outcomes in every area of life. When Black lives are systemically devalued by society, our outrage justifiably insists that attention be focused on Black lives. When a church claims boldly "Black Lives Matter" at this moment, it chooses to show up intentionally against all given societal values of supremacy and superiority or common-sense complacency. By insisting on the intrinsic worth of all human beings, Jesus models for us how God loves justly, and how his disciples can love publicly in a world of inequality. -

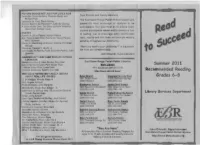

Summer 201 1 Recommended Reading Grades

PICTURE BOOKS/NOT JUST FOR LITTLE KIDS Incredible Cross-Sections. Stephen Biesty and Dear Parents and Family Members, Richard Platt The East Baton Rouge Parish School System and Leonardo da Vinci, Diane Stanley So You Want to Be President? Judith St. George community must encourage all students to be A Voice ofHer Own. The Story of Phillis Wheatley, avid readers. Our goal must be to ensure every Slave Poet, Kathryn Lasky student is a capable reader and to develop a love POETRY of reading. Let us encourage every child to read Carver: A Ufe in Poems, Marilyn Nelson Ego-Tripping and Other Poems for Young People, daily, read to and with them and promote reading Nikki Giovanni activities throughout our community. Poetry for Swimming Upstream, Kristme O'Connell George "Have you read to your child today?" is a question Rlmshots, Charles R. Smith, Jr. Technically It's Not My Fault: Concrete Poems, John we must ask ourselves daily. Grandits John Dilworth, Superintendent WANDERLUST/ DISCOVER WORLDS OUTSIDE LOUISIANA Baseball in April & Other Stories, Gary Sota East Baton Rouge Parish Public Libraries Becommg Naomi Leon. Pam Munoz Ryan Main Library Summer 201 1 Children of the River, Linda Crew 7711 Goodwood (225) 23 1-3740 Chinese Cinderella, Adeline Yen Mah http://www.ebr.lib.la.us/ Recommended Reading WHO SA YS FICTION ISN'T REAL? (BOOKS ABOUT REAL LIFE ISSUES) Baker Branch Greenwell Springs Road Grades 6-8 11 Birthdays, Wendy Mass 3501 Groom Road 11300 Greenwell Spnngs * (225) 778-5940 (225) 274-4440 Bird, Angela Johnson Boys are Dogs, Leslie Margolis Bluebonnet Branch Jones Creek Branch Brand-New Emily. -

X: a Novel by Ilyasah Shabazz with Kekla Magoon

X: a Novel by Ilyasah Shabazz with Kekla Magoon This riveting and revealing novel follows the formative years of the man whose words and actions shook the world. X follows Malcolm from his childhood to his imprisonment for theft at age twenty, when he found the faith that would lead him to forge a new path and command a voice that still resonates today. Why you'll like it: Compelling, candid, emotional, suspenseful About the Authors: Ilyasah Shabazz, third daughter of Malcom X, is an activist, producer, motivational speaker and author of Growing Up X. Shabazz explains that it is her responsibility to tell her father’s story accurately. She believes “his life’s journey will empower others to achieve their highest potential.” Kekla Magoon is a writer, editor, speaker, and educator. She is the author of Camo Girl, 37 Things I Love (in No Particular Order), How It Went Down, and numerous non-fiction titles for the education market. Her book, The Rock and the River, won the Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award. She also leads writing workshops for youth and adults and is the co-editor of YA and Children's Literature for Hunger Mountain, the arts journal of Vermont College. (Bowker Author Biography) Questions for Discussion 1. Instead of telling the story in chronological order, the author moves back and forth through time. What effects does this have on the story? What is this important to the story? 2. Early in the story, Malcolm says “I am my father’s son. But to be my father’s son means that they will always come for me” (page 5). -

Identity of African American Characters in Newbery Medal and Newbery Honor Award Winning Books: a Critical Content Analysis of B

IDENTITY OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CHARACTERS IN NEWBERY MEDAL AND NEWBERY HONOR AWARD WINNING BOOKS: A CRITICAL CONTENT ANALYSIS OF BOOKS FROM 1991 TO 2011 Tami Butler Morton, B.A., M.T. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2012 APPROVED: Janelle Mathis, Major Professor Elizabeth Figa, Minor Professor Carol Wickstrom, Committee Member Claudia Haag, Committee Member Nancy Nelson, Chair of the Department of Teacher Education and Administration Jerry Thomas, Dean of the College of Education Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Morton, Tami Butler. Identity of African American Characters in Newbery Medal And Newbery Honor Award Winning Books: A Critical Content Analysis of Books from 1991 to 2011. Doctor of Philosophy (Reading), December 2012, 119 pp., 14 tables, 3 illustrations, references, 80 titles. The purpose of this study was to conduct a critical content analysis of the African American characters found in Newbery Medal award winning books recognized between the years of 1991 and 2011. The John Newbery Medal is a highly regarded award in the United States for children’s literature and esteemed worldwide. Children’s and adolescents’ books receive this coveted award for the quality of their writing. Though these books are recognized for their quality writing, there is no guideline in the award criteria that evaluated the race and identity of the characters. Hence, there are two overarching research questions that guided this study. The first question asked: To what extent are the African American characters in each award winning book represented? Foci in answering this question were the frequency of African American characters and the development of their ethnic identities. -

Books How to Be Antiracist by Ibrahim X Kendi Mindful of Race

Books How To Be Antiracist by Ibrahim X Kendi Mindful of Race: Transforming Racism from the Inside Out by Ruth King So You Want To Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo The Inner Work of Racial Justice by Rhonda V. Magee The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism For The Twenty-First Century by Grace Lee Boggs This Bridge Called My Back: Writings By Radical Women Of Color by Cherrie Moraga White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People To Talk About Racism by Robin Diangelo White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide by Carol Anderson, PhD Racial Healing by Anneliese A. Singh, PhD The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the age of colorblindness by Michelle Alexander. Infant and preschool books Anti-Racist Baby also by Ibrahim X Kendi Whose Toes Are Those? by Jabari Asim (0-3) Yo! Yes? (Scholastic Bookshelf) by Chris Raschka (2-4) Young Water Protectors: A Story About Standing Rock by Aslan & Kelly Tudor (ages 3-8) The Day You Begin by Jacqueline Woodson (ages 4-8) When We Were Alone by David A. Robertson (4-8) Skin Like Mine (Kids Like Mine) by LaTashia M. Perry (1-12) Children’s books A Is For Activist by Innosanto Nagara Let the Children March by Monica Clark-Robinson Separate is Never Equal by Duncan Tonatiuh (ages 6-9) Sulwe by Lupita Nyong’o Malala’s Magical Pencil by Malala Yousafzai Kid Activists by Robin Stevenson Last Stop on Market Street by Matt De La Pena Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness by Anastasia Higginbotham Malcolm Little: The Boy Who Grew Up to Become Malcolm X by Ilyasah Shabazz (ages 6-10) Let it Shine: Stories of Black Women Freedom Fighters by Andrea Davis Pinkney (ages 6-9) Unstoppable: How Jim Thorpe & the Carlisle Indian School Football Team Defeated Army by Art Coulson (ages 6-10) Schomburg: The Man Who Built a Library by Carole Boston Weatherford (9-12) Viola Desmond Won’t Be Budged! by Jody Nyasha Warner and Richard Rudnicki (5-9) My Hair is a Garden by Cozbi A. -

Norristown Area High School Summer Reading List: Grade 11 (Current 10Th Graders)

Norristown Area High School Summer Reading List: Grade 11 (Current 10th graders) All Non AP English III students The teachers of Norristown Area High School feel that it is important for students to continue to work on acquiring, maintaining and improving reading and analysis skills through the summer months as well as appreciating literature and reading for personal enjoyment. To that end, the teachers in the English department have put together the following lists of suggested titles for grade 11. Non-Weighted Honors--Choose one book from below for the Independent Reading Student Choice. No assignment required. Weighted Honors--Choose one book from below for the Independent Reading and complete a double entry journal of at least 20 entries for one of the following books. American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang (Graphic Novel) -- American Born Chinese is the first graphic novel to be nominated for a National Book Award and the first to win the American Library Association's Michael L. Printz Award. An intentionally over-the-top stereotypical Chinese character make this a better fit for teen readers who have the sophistication to understand the author's intent. Three parallel stories interlock in this graphic novel. In the first, the American-born Chinese boy of the title, Jin, moves with his family from San Francisco's Chinatown to a mostly white suburb. There he's exposed to racism, bullying, and taunts. The second story is a retelling of the story of the Monkey King, a fabled Chinese character who develops extraordinary powers in his quest to be accepted as a god. -

Children's Book and Media Review Volume 37 Article 29 Issue 11 November 2011

Children's Book and Media Review Volume 37 Article 29 Issue 11 November 2011 2016 X Carlie Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Smith, Carlie (2016) "X," Children's Book and Media Review: Vol. 37 : Iss. 11 , Article 29. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr/vol37/iss11/29 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Children's Book and Media Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Smith: X Book Review Title: X Author: Ilyasah Shabazz with Kekla Magoon Reviewer: Carlie Smith Publisher: Candlewick Press Publication Year: 2015 ISBN: 9780763669676 Number of Pages: 348 Interest Level: Young Adult Rating: Excellent Review Before he was X, Malcolm had many titles: son, brother, Negro, dancer, Detroit Red, and thief. This novel explores Malcolm’s early years before he became one of the most influential civil rights activists. Haunted from an early age by the injustice of his father’s assassination and his mother’s confinement in a mental institution, Malcolm quickly learned street survival skills. He leaves Lansing, Michigan for the progressive Roxbury neighborhood of Brooklyn and falls in love with the dancing clubs, zoot suits, and “cool cat” hustlers. He sheds his small-town identity to become Red, a petty criminal, the boyfriend of a white woman, and friend of jazz musicians. Work opportunities lead Malcolm to Harlem where he becomes an associate of Sammy the Pimp and bookie West Indies Archie. -

African American Main Characters

African American Main Characters As Brave as You My Life as an Ice Cream by Jason Reynolds Sandwich When Genie and his older brother spend by Ibi Aanu Zoboi their summer in the country with their In the summer of 1984, Ebony-Grace of grandparents, he learns a secret about Huntsville, Alabama, visits her father in his grandfather and what it means to be Harlem, where her fascination with outer brave. space and science fiction interfere with J Fiction Reynolds, Jason her finding acceptance. J Fiction Zoboi, Ibi Trace by Pat Cummings The Long Ride When Trace sees a ghost wearing by Marina Tamar Budhos old-fashioned clothing in the basement of In New York in 1971, Jamila and Josie are the New York Public Library, he discovers bused across Queens where they try to fit that the boy has ties to Trace's own in at a new, integrated junior high school history, and that Trace may be the key to while their best friend, Francesca, tests setting the dead to rest. the limits at a private school. J Fiction Cummings, Pat J Fiction Budhos, Marina Tamar Some Places More than Mia Mayhem is a Superhero! Others by Kara West by Renée Watson Eight-year-old Mia Macarooney is Amara visits her father's family in Harlem delighted to learn she is from a family of for her twelfth birthday, hoping to better superheroes, but her acceptance into the understand her family and herself, but Program for In Training Superheroes New York City is not what she expected. requires she take a placement exam. -

Printz Award Winners

The White Darkness The First Part Last Teen by Geraldine McCaughrean by Angela Johnson YF McCaughrean YF Johnson 2008. When her uncle takes her on a 2004. Bobby's carefree teenage life dream trip to the Antarctic changes forever when he becomes a wilderness, Sym's obsession with father and must care for his adored Printz Award Captain Oates and the doomed baby daughter. expedition becomes a reality as she is soon in a fight for her life in some of the harshest terrain on the planet. Postcards From No Man's Winners Land American Born Chinese by Aidan Chambers by Gene Luen Yang YF Chambers YGN Yang 2003. Jacob Todd travels to 2007. This graphic novel alternates Amsterdam to honor his grandfather, between three interrelated stories a soldier who died in a nearby town about the problems of young in World War II, while in 1944, a girl Chinese Americans trying to named Geertrui meets an English participate in American popular soldier named Jacob Todd, who culture. must hide with her family. Looking for Alaska A Step From Heaven by John Green by Na An YF Green YF An 2006. 16-year-old Miles' first year at 2002. At age four, Young Ju moves Culver Creek Preparatory School in with her parents from Korea to Alabama includes good friends and Southern California. She has always great pranks, but is defined by the imagined America would be like search for answers about life and heaven: easy, blissful and full of death after a fatal car crash. riches. But when her family arrives, The Michael L. -

Author Alex Haley on a Greenwich Village Building American History,” She Said

MAYOR DE BLASIO IS SEEKING DEMOCRATIC NOD FOR PRESIDENT - P G. 2 NATIONAL NEWSPAPER PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION THE NATION’S ONLY BLACK DAILY Reporting and Recording Black History 75 Cents Final VOL. 48 NO. 54 FRIDAY, MAY 17, 2019 GREENWICH VILLAGE HONORS ‘ROOTS’ AUTHOR ALEX A commemorative plaque living there. After the auto - was placed on Hthis bAuilding LbioEgraphY y was published, at 92 Grove Street in Green - Haley's next project was the wich Village to honor Alex Pulitzer Prize winning Haley who co-authored Mal - "Roots: The Saga of An Amer - colm X's autobiography after ican Family," which became a conducting 50 interviews popular television series. with him at the site while SEE PAGE 3. DAILY CHALLENGE FRIDAY, MAY 17, 2019 3 A historic plGaqure ehase benenw plaicecd hth aVt twiol Alfaricgan eAm ehricaonsn plaoyedr isn ‘Roots’ author Alex Haley on a Greenwich Village building American history,” she said. “Their where “Roots” author Alex Haley lived cultural impact can be preserved to and co-authored the autobiography of spark educational exploration for Malcolm X. future generations…” The plaque was placed at 92 Grove Zaheer Ali, oral historian at the Street in a brief ceremony attended by Brooklyn Historic Society, said the descendants of both men. building “is more than historic, it’s “Few places are as important as 92 sacred.” Grove Street, where a historic meeting “In this intimate space, Malcolm X of the minds took place between Alex offered up his life story before an audi - Haley and Malcolm X for a series of ence of one,” Ali said.